Despite the economic challenges that markets all over the globe continue to face, many industries—including basic materials, oil and gas, and utilities—have large-scale projects in the works. Over the next four years, for example, the top ten mining companies together plan to spend more than $200 billion on capital projects related to spending categories such as machinery, infrastructure, and engineering services.

Such capital projects are typically very large investments, often representing more than 10 percent of a company’s annual revenue, depending on the industry. Notably, too, external capital spending can represent 80 percent or more of a project’s total budget. Many companies have established dedicated capital-procurement functions and have put project-specific procurement teams in place. Those companies regularly update their supply strategies for important equipment and service categories and clearly define core processes such as cost escalation estimation and claims management (the process of negotiating paybacks related to changes in project plans, unexpected cost increases, or quality problems). Standard project procedures and handbooks mandate that project compliance be monitored closely. (See “The Dos and Don’ts of Capital Procurement.”)

The Dos and Dont's of Capital Procurement

In our experience, companies with successful capital-procurement programs ensure that ten elements are in place and avoid ten common stumbling blocks.

Successful companies do the following:

- Establish the transparency of category spending across the project portfolio.

- Ensure the involvement of the procurement function as early as the concept phase of every project.

- Streamline project approval processes to ensure that procurement has sufficient lead-time to secure the best possible proposals from suppliers.

- Develop a clear profile of accountabilities and required skills for project procurement managers, especially in the case of large projects.

- Build a dedicated team of procurement experts focused on both overall and project-specific procurement.

- Clearly define cross-functional procurement processes as part of a project handbook.

- Establish a total-cost-of-ownership perspective with regard to key equipment and investment decisions.

- Track project and partner performance based on KPIs that address project performance and progress, as well as procurement effectiveness and supplier cost performance.

- Systematically evaluate alternative contracting models and incentive schemes on the basis of project complexity and size.

- Actively monitor compliance with procurement processes, including subcontractors that assume procurement tasks.

Successful companies don’t do the following:

- Make unrealistic assumptions regarding addressable spending volumes. Instead, they clarify the share of committed spending volumes for every project.

- Allow ambiguity on cross-project demand. Rather, they use standard project and equipment structures to define work packages.

- Avoid regular interaction with key stakeholders. They interact with stakeholders using a consistent platform for the procurement and project management functions.

- Lock in suppliers too early. Successful companies don’t let engineers and design personnel make commitments with potential suppliers prematurely, because doing so limits supply options and precludes competitive contracting.

- Take an unfocused, overly broad approach to optimizing categories. Rather, they prioritize spending areas with short-term impact and strategic importance and ensure that sourcing strategies are fully developed and implemented systematically.

- Put insufficient focus on the procurement performance of third parties. Successful companies ensure that procurement-related incentives are agreed upon as part of their arrangements with major project partners and contractors.

- Overlook project-specific dynamics. Instead, they consider project timelines and constraints in cross-project approaches, such as bundling.

- Fail to define procurement career paths and roles. Successful companies attract procurement talent by clearly defining career paths.

- Fail to clearly calculate savings. It is better to provide clear guidelines on how value is defined and how potential savings should be specified.

- Focus too restrictively on project delivery. Instead, successful companies review procurement strategies and timelines in light of changing project business cases (in an economic downturn, for example).

In practice, however, many companies continue to struggle to establish a consistent approach to capital procurement, and they suffer various consequences:

- They experience poor capital-procurement performance and significant deviations from established budgets and schedules, as well as from benchmark cost levels.

- They do not identify and manage supply-related risks early enough, and thus they suffer from increased capital expenditures and operational costs relative to initial plans—as well as frequent extensions of lead-time for critical equipment.

- They lack a cross-project perspective, which keeps them from sharing best-practice designs, leveraging aggregate demand, and establishing partnerships with key suppliers on a global level.

- They lack the tools needed to manage decisions effectively, track the impact of decisions across the project life cycle, and monitor the performance of procurement activities or suppliers in individual projects.

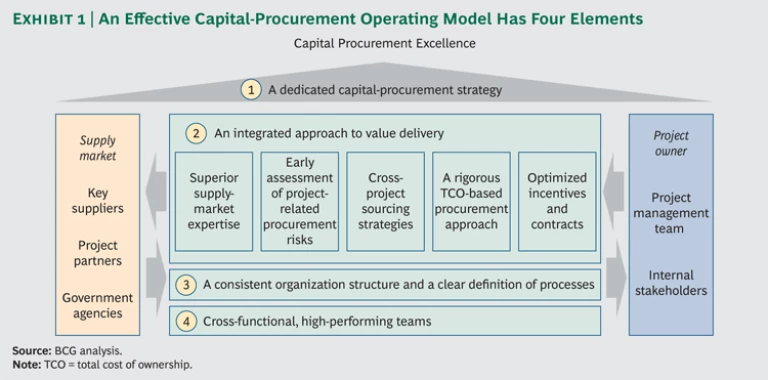

On the basis of projects that The Boston Consulting Group has worked on with clients, we have identified four building blocks of a successful capital-procurement operating model that can be applied by companies across many industries:

- A dedicated capital-procurement strategy that considers the specifics of the supply market, the capabilities of the company, and the requirements for the successful delivery of capital projects

- An integrated approach to value delivery and risk management in the procurement of project-related goods and services

- A consistent organization structure as well as a clear definition of processes

- The development and enablement of high-performing cross-functional teams

This model, when aligned properly with both internal and external stakeholders and consistently applied, can sustainably improve the performance of a company’s capital-procurement function. Companies using this model can save as much as 15 percent of a capital project’s net present value while reducing risk and ensuring that budgets and timelines are met. These building blocks are critical to establishing competitive price levels across key spending areas and ensuring that project-related supply risks are appropriately managed. (See Exhibit 1.)

A Dedicated Capital-Procurement Strategy

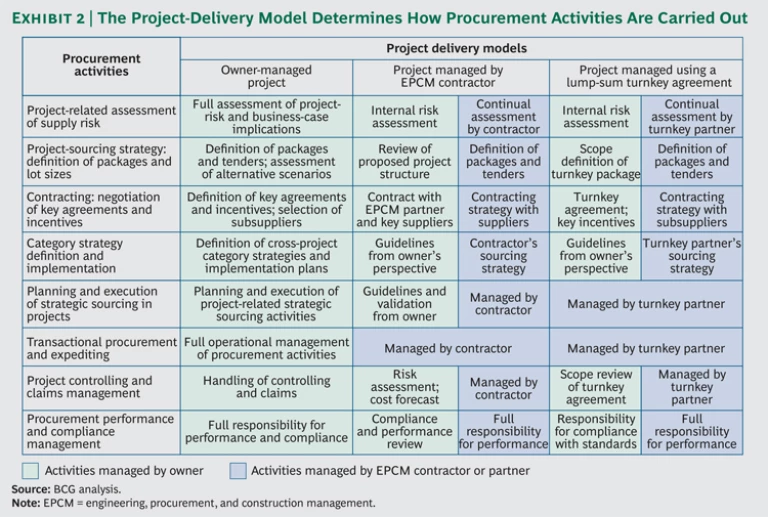

The right approach to capital procurement should be closely linked to a company’s project-delivery strategy. In practice, a variety of project delivery models can be applied: strong leadership from the owner, management primarily by a contractor or outside engineering company, and execution based on a lump-sum turnkey agreement.

- Owner-Managed Projects. If a company can rely on its own capabilities to engineer a solution and to execute and manage a capital project in a specific geographic region, an owner-managed approach to project engineering and management is an option. Under these circumstances, the procurement function serves as a partner for the project management team, helping it to assess and manage project-related risks, outsource specialized tasks, and establish a project-related sourcing strategy that aims to leverage spending volumes as well as procurement activities beyond the particular project’s scope.

- Projects Managed with the Support of an Engineering, Procurement, and Construction Management (EPCM) Contractor. These projects will likely involve engineering partners and equipment suppliers, which often play an important part in supporting the project owner in managing the project, defining major parts of the project design, and providing access to critical supply networks in remote regions. An EPCM partner typically complements and leverages the capabilities of an owner’s team. It will drive the engineering solution as well as the execution of the project; however, the project owner continues to bear the ultimate project risk. Typically, an EPCM partner is incentivized through a bonus scheme linked to the project’s success. When an EPCM partner model is used, the procurement organization should focus on establishing relationships with key suppliers, including the engineering companies and equipment suppliers. In those cases, providing partners with guidance on sourcing strategies and evaluating partners’ procurement performance and related project risks on an ongoing basis are critical strategic procurement capabilities.

- Projects Managed Using a Lump-Sum Turnkey Agreement. Using this model, a project partner will contract to deliver the completed project on time and for a defined total cost. This can be an appropriate project model when internal capabilities are limited and project-related risk should be avoided. The premium paid for delivering a project at minimal risk will depend on the nature of the project and the availability of other suppliers; in a very competitive market, the premium can be high. In the case of large projects, the project partner may not be willing to bear all the execution risk if that risk is so high that no risk premium could compensate for the threat of significant losses on the project. Once the sourcing strategy is determined and project partners are selected, opportunities to influence the project’s cost structure will likely become very limited. The procurement function must get involved early to assess all the potential contracting options and incentive structures and to help select contractors, rather than supporting sourcing activities only once the project is under way.

The appropriate delivery model depends on a range of factors and determines how the many critical activities involved in procurement are carried out. (See Exhibit 2.) A portfolio with numerous projects will likely include more than one approach.

Given the variety of possible delivery models, it is critical that the procurement team’s primary role (including how and where it can best create value) is clearly defined within the context of the delivery model chosen for the project at hand. To that end, the leaders of the company’s procurement function must make clear to individual project-management teams and internal customers when support will be necessary and what form that support should take, depending on the delivery model chosen. The procurement organization will also determine how to manage relations between partners, by assessing past project performance and the best strategic procurement practices across key spending categories.

An Integrated Approach to Value Delivery

The goal of a best-practice capital-procurement organization should be to seek opportunities to deliver additional value, beyond the scope of the strategic sourcing tasks required for each individual project. Succeeding in this task requires a deep knowledge of the supply market and a perspective that takes into account the entire life cycle of each project across the entire project portfolio.

Taking a broad view of procurement opportunities that goes beyond each individual project can reveal numerous ways to boost value across the procurement spectrum:

- Supplier Management. Repeated collaborations with strategic supply partners can minimize inherent project risks for both sides and allow for improved contract terms across projects.

- Bundling. Project owners can increase their buying power and realize scale opportunities by bundling demand across projects or combining project-related and ongoing spending volumes.

- Process Optimization. Repeated collaborations with key project partners and contractors, and the establishment of joint project-management standards, can allow for reduced costs and greater efficiency of service delivery.

- Sourcing in Best-Cost Countries and Localization. A clear view of the project pipeline within a region allows companies to identify and develop qualified local suppliers in those countries in a specific region that offer the lowest costs, with the objective of providing services, products, and components across a range of projects.

- Demand Management. Companies can increase the value of their projects by effectively managing their order pipelines for equipment and analyzing the demand for resources in key categories across projects.

- Standardization and Redesign. Owners can gain efficiency by reusing and optimizing important design elements and equipment across projects.

- Optimized Make-or-Buy Decisions. The effective assessment of the best mix of internal and external services needed for each project, based on a full understanding of all partners’ capabilities, can optimize the value created for every party involved.

- Supply Risk Management. The understanding and management of project risk can be improved through repeated collaborations with select suppliers; that pattern can result in reduced risk premiums in the products and services of suppliers and partners.

Companies that consistently capture the most value from their capital projects typically excel at five critical procurement capabilities:

- Superior supply-market expertise

- Early assessment of project-related procurement risks

- Cross-project sourcing strategies

- A rigorous procurement approach based on the total cost of ownership (TCO)

- The use of incentives and contracts designed to optimize partners’ performance

Superior Supply-Market Expertise

The highly cyclical nature of the demand for project-related equipment and services requires in-depth knowledge of key supply markets. Project owners must make significant efforts to assess market trends for supplies from a cross-project perspective, with a multiyear horizon, in order to support strategic procurement decisions.

Companies must be able to anticipate how changes in specific supply markets or regions can affect their sourcing strategies. The transition from a seller’s market for supplies, where the focus should be on the active management of cost-escalation and lead-time risks, to a buyer’s market, where long-term contracts need to be actively reviewed so that the buyer can benefit from declining price levels, can often happen within months. (See “Market Changes and Capital Budgets.”)

Market Changes and Capital Budgets

Excellence in capital procurement is particularly important in situations in which changes in the market environment have a profound impact on the project’s underlying business case.

For example, in recent months, major mining companies have reduced their capital budgets by 20 to 30 percent, owing to a weaker outlook for commodity prices. Although the reduced budgets resulted in the cancellation of projects, reduced capex budgets more frequently lead to a reassessment of the project-sourcing strategies to accommodate the lower capex budget.

Reduced commodity prices and lower opportunity cost from delayed projects offer the opportunity to stretch project deadlines. As a result, project cost increases may be avoided because certain specific expenses, such as express deliveries or overtime payments for services, will not be required. Tender and negotiation processes may be extended, given that a changed market environment offers the opportunity to review price premiums that were established in periods of strong supply markets. A systematic reassessment of the project’s overall costs is crucial in these situations, to understand the current level of commitments across commodities and to identify remaining addressable costs.

A high level of supply market expertise was instrumental for a leading global mining company in defining its approach to the purchase of critical equipment. The company’s goal was to narrow its supply base across numerous projects by analyzing global equipment demand. A forecast model based on historic investment patterns for key equipment categories in the mining industry allowed the company to predict an upcoming reduction in equipment demand. This finding, in turn, helped the company to shape its negotiation strategy across its project portfolio, putting greater emphasis on demand consolidation, tendering, and TCO analysis, despite brief timelines and urgent needs across numerous individual projects.

On the basis of the insights it gained into the supply market, the company was able to approach the market using a coordinated sourcing effort at the right moment, resulting in cost reductions of more than $100 million, which helped it reestablish its competitive cost position.

Early Assessment of Project-Related Procurement Risks

Every cross-functional project-leadership team needs to assess the procurement-related risks and tradeoffs, beyond the technical aspects and feasibility of a project, early in the planning process as part of the overall business case. These might include the impact of project-sourcing strategies on related supply risks and the need to adhere to local-content regulations. The goal of this upfront assessment is to identify the optimum solutions with regard to project delivery, structure, and risk.

Project Delivery. Companies will likely employ one of three methods of project delivery, as described earlier: owner-managed approaches, partnerships with specialized service partners such as EPCM contractors, and lump-sum turnkey solutions. The procurement function should actively support the early assessment of the best approach to designing and completing each project. This assessment involves the consideration of the company’s own capabilities, the project’s risk structure, and the willingness of key partners to bear some of the risks of the project under acceptable commercial conditions. It therefore requires a realistic look at the supply options for critical components, skills, and services, such as the availability of skilled engineering-services providers in the targeted region.

Project Structure and Scope. Typically, a project owner’s partners and key suppliers will offer several options for combining packages of equipment and project-related services. However, different approaches with regard to the project structure can have a significant impact on procurement cost, project complexity, and other important performance dimensions, such as adhering to regulatory requirements and local-content targets. A dedicated scenario analysis of each project’s supply and sourcing strategies can help project owners make the appropriate decisions and leverage their bargaining power in discussions with the key project partners.

A major oil and gas company recently evaluated its options for structuring a project requiring a multibillion-dollar investment. The company sought to segment the project-related tasks among suitable equipment suppliers and related engineering partners with the goal of balancing the project’s complexity, the potential for bundling high-volume purchases, and the fulfillment of local-content requirements. The need for a systematic risk assessment and the joint-venture structure of this particular project required a fact-based assessment of the ideal project setup over the five-year project life cycle.

In its assessment, the company employed a scenario approach that addressed several concerns regarding the optimal structure of the different work packages, equipment requirements, and services to be rendered. The company developed scenarios for allocating tasks and awarding responsibilities for work packages to different partners and then evaluated those scenarios in the light of significant risk factors, including how to minimize the number of interfaces to be managed across the project, how to fulfill local-content requirements, and how to deliver the project in the most economical and low-risk way possible.

Each scenario was then assessed from both a commercial perspective and a project risk perspective, an approach that allowed the company to quantify the potential impact of delays and quality issues. The risk assessment helped support an efficient, fact-based decision-making process among the key stakeholders.

Due Diligence in Reviewing Project Risk. The early review of a project’s supply-related risks is generally part of its overall risk assessment. The procurement function can add further value by assessing the project’s scope, on the basis of a detailed knowledge of inbound supply chains and logistical requirements. For projects that involve complex, long-term deliveries across several divisions, the procurement organization must assess key assumptions about the project’s major interfaces, such as project demand and any additional infrastructure investments that may be required.

In one recent case, a potential partner offered a project owner, a utility company, a long-term supply agreement based on an investment of several hundred million dollars. At first glance, the partner’s feasibility study suggested a robust business case for the project, one that reflected apparently appropriate assumptions about potential changes in supply market prices and capex budgets. A more detailed analysis, however, revealed several project risks—including a lack of transport infrastructure and greater-than-expected future demand for the necessary supplies—that were not visible to the project partner because they involved the project owner’s operations.

As a result, several elements of the proposed supply agreement had to be renegotiated, resulting in such changes as a postponed but more aggressive ramp-up phase for the project. This ensured that the planned investment matched the project owner’s demand more closely.

The analysis also identified other risks, including those involved in investing in complementary infrastructure to facilitate the shipment of the commodities produced by the project. So the project owner provided additional support to the supplier in the completion of the project as well as in the management of key stakeholders, including the government agencies responsible for transport infrastructure and environmental permits.

Cross-Project Sourcing Strategies

Companies whose capital procurement activities focus on individual projects miss the opportunity to leverage cross-project experience and buying power, even if those individual projects are well executed. If cross-project strategies are to succeed, certain elements need to be established:

- Transparency is essential, particularly as it relates to the addressable project cash flow, realistic savings targets, and value-creating impact across all projects.

- A standard approach to the development of category procurement strategies must be aligned with project-specific objectives through dedicated cross-functional category committees. For companies with many projects, this also requires an effective process for developing a global supplier base, independent of individual-project requirements, to ensure the qualification of new suppliers prior to the start of new projects.

- The effective combination of project-specific procurement activities and category-specific strategic sourcing activities can be achieved on the basis of an understanding of each project’s timeline and the lead-time required for strategic sourcing activities and negotiations.

- A clear negotiation and partnering strategy aimed at capturing the benefits of the repeatable use of standardized designs for key equipment, construction packages, and related services should also include the establishment of standard contract models that cover requirements for equipment installation and service.

As it planned the construction of several new power plants recently, a leading utility identified the potential replication of the initial design in each subsequent plant as a key value opportunity. So it focused the tender process for the first plant on reusable design components and economies of scale and placed great weight on the potential suppliers’ ability to build the subsequent projects efficiently. Ultimately, the performance-related agreements it made with the winning engineering-services providers and technology suppliers enabled it to reap the benefits of the repetitive collaboration with them, including a reduction in the effort needed to carry out the proposed activities in the offer phase of each project and a reduction of engineering effort across all the projects.

A Rigorous TCO-Based Procurement Approach

When companies make early project-investment decisions in a high-growth environment, all too often they focus largely on completing the project on time, without paying adequate attention to subsequent operating costs.

A TCO-based investment-decision model helps maintain the focus on subsequent life-cycle costs during supplier selection and negotiation. Appropriate TCO-based models should be based on recent company-specific data, which should establish a proprietary perspective. As such, a TCO model can serve as an effective support in negotiations with partners, through its focus on both the initial capex and the subsequent operating costs. (See “Value Engineering.”) Additionally, key performance dimensions should be considered, such as the impact of equipment selection on product quality or equipment uptime. Such models also provide a clearer view of differences in the cost base and operating conditions from country to country.

Value Engineering

A realistic understanding of the TCO was the starting point for a collaborative value-added engineering effort between a major engineering company and a key equipment supplier. On the basis of a jointly developed perspective on how engineering specifications would affect the TCO of key equipment, both parties identified savings opportunities of up to 20 percent. An initial agreement to share the benefits of the joint optimization of solutions was a significant factor in gaining the supplier’s buy-in. The collaboration included optimized equipment specifications, the use of select components from best-cost-country sources, and best-practice logistics and quality-inspection procedures.

Often, this enhanced level of insight will enable a profound global benchmarking of operations and the rollout of best practices in the operational phase of projects, revealing the time frame for the depletion of various consumable supplies, for example.

One leading global mineral-resources company overcame the difficulty of establishing an integrated approach to total life-cycle costs by establishing a systematic approach to TCO management, which became a centerpiece of the company’s procurement and operations strategy for mobile and fixed mining equipment. In the past, tenders had been analyzed on the basis of TCO-related information, some of which was provided by suppliers. The project owner could not challenge these assumptions during the negotiation phase because it had little insight into its own internal data regarding TCO, including fuel consumption levels and the true cost of servicing and spare parts. As a result, its assumptions regarding costs were overly optimistic.

As part of its new TCO strategy, the owner used its own proprietary data to analyze a total of $800 million in capex. The company’s procurement organization also standardized the TCO models used by all of its sites, while taking into account country-specific differences in areas such as fuel prices. The new approach gave the company the confidence to contract out about 80 percent of its volume in mobile equipment to one supplier, on a long-term basis, leading to $100 million in annual savings.

Optimized Incentives and Contracts

Designing an appropriate incentive structure that benefits all of a project’s partners is crucial to completing the project successfully and sharing the risks fairly. The willingness of partners to take on some portion of the project risk will inevitably be linked closely to the options each supplier might have for deploying its resources elsewhere. The key elements of any potential agreement must be reviewed and optimized, and any opportunities to capture additional benefits from repetitive collaboration, such as increased know-how, scale effects, and the reuse of components, must be actively assessed and pursued across the project portfolio.

A Consistent Organization Structure and a Clear Definition of Processes

Well-documented cross-functional processes and clear collaboration rules are critical if the procurement function is to be successfully integrated into every project. The commodity-purchasing teams and the project procurement professionals need to work together closely to define all procurement-specific milestones and deliverables. A dedicated project-procurement manager will usually serve as the link between the procurement function and each project throughout the project’s life cycle.

Every project plan must include definitions and timetables for all the major milestones, including the completion of the final sourcing plan, the definition of the scope of project-specific tenders and work packages, and early and regular reviews of all cross-project sourcing opportunities. The performance of the procurement function itself should be assessed on an ongoing basis, and external partners should be included in the assessment process.

The importance of effective organization can be seen in the case of a leading global-resources company. The company had successfully established a corporate procurement department, but aligning all the procurement experts—each with responsibility for different spending areas, different projects, and several hundred million dollars in spending—remained a challenge. A primary reason was that projects were not being consistently organized; 40 percent of projects, for instance, had no dedicated procurement manager.

By establishing an enterprise-wide approach to the development of every project and identifying high-caliber professionals to represent procurement at the project leadership level, the company succeeded in fully integrating the procurement function with each project. The resulting improvements in collaboration between procurement and project management enabled the company to generate savings of up to 10 percent of the total budget for all of its projects.

Cross-Functional, High-Performing Teams

In practice, the role of the project procurement function will vary depending on the nature of each project. So the project procurement function must possess the flexibility and expertise to operate smoothly and efficiently under every project-delivery circumstance. Projects managed entirely in-house need to be led by a strong project manager with a good understanding of the importance of a clear sourcing strategy and the early involvement of procurement. For projects delivered through an EPCM or turnkey agreement, the procurement function’s role is primarily to negotiate the contract terms, incentives, and agreements with the primary contractor, whether it be an engineering services team or a turnkey partner.

A leading global petrochemical company was facing different requirements for the degree of in-house project-procurement support needed on a variety of projects, depending on the size of the capex investment in each project and the degree to which the management of each project was outsourced. Using a customer-driven approach, the procurement function established with the project management team a standard catalog of procurement-related activities. The catalog defined the role of procurement as an internal service provider in the context of different project-delivery models, which helped to reduce significantly the ambiguity with regard to the support of different projects. The project management team also participated in the definition of the skills needed by project procurement managers, thus providing guidance on the recruitment of people to fulfill the required activities.

Key Success Factors

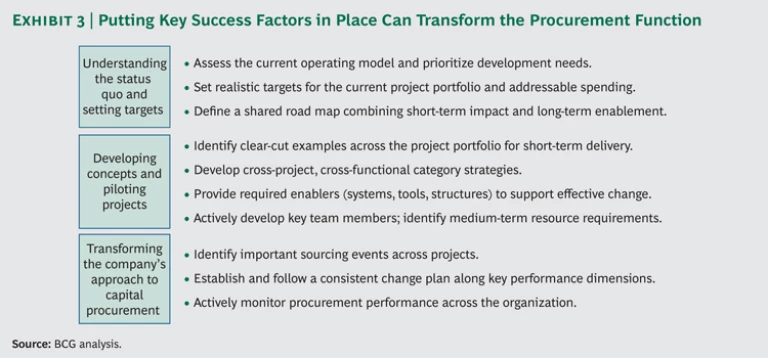

Given the criteria needed for a successful capital-procurement function, how best should companies go about establishing an effective operating model for the function?

In the case of larger procurement organizations, these changes require a coordinated cross-functional approach, involving both the engineering and project-management functions. Building the model itself will require working in stages, first assessing in detail the procurement function’s current model, and then developing a multiyear plan for moving to the new model. (See Exhibit 3.)

Understanding the Status Quo and Setting Targets

No transition plan can succeed without an awareness of what needs to be changed. A good starting point is to systematically assess past performance, making sure to answer the following questions:

- How do we currently gather benchmarking and performance information regarding our project-specific suppliers? How are these findings translated into procurement strategies across all our projects?

- What are the current key spending categories and value drivers in each category? How can we leverage them across all our projects?

- Which critical procurement-related risks have we faced in our recent projects? How can procurement contribute to managing them, and which incentive structures should be put in place?

- What are the capabilities that need to be developed to establish best practices in capital procurement?

- How can we transform our current processes to successfully establish sustainable procurement capabilities while creating short-term value?

Our experience working with clients suggests that an approach that combines the rapid application of best-practice concepts in pilot areas and the adherence to a realistic road map is the best way to transform the capital procurement function.

Developing Concepts and Piloting Projects

While the process of generating new ideas for capital procurement can often be accomplished within a small team, applying new approaches more broadly is a roadblock common to transformation efforts. Therefore, it is critical to establish an early focus on the practical application of new ideas by applying them selectively in pilot projects; this will enable the team to work on the implementation process in a narrow, controlled context, and it will establish a robust concept for further rollout.

Transforming the Company's Approach to Capital Procurement

As challenging as the concept-generation and piloting stage is in the establishment of procurement excellence, managing the transition from initiative to “business as usual” across the entire project pipeline can be even more difficult. In preparing for the transition, it is critical to plan the establishment of the required infrastructure in parallel with support for the procurement team. This includes both the tools and the systems needed, such as a TCO-based database and a project-demand-planning tool, as well as the overall organization structure. Companies must also identify the critical roles that will need to be filled in the new organization, such as the category managers and project procurement managers, and invest in the right people to put in those roles.

Once the new system is ready to be rolled out, companies must establish and follow a consistent plan for change along all the key performance dimensions. They must identify the important sourcing events (such as tender awards and upcoming major negotiations) across the entire project landscape and actively monitor procurement performance across the team.

Finally, reliable metrics need to be established to track the timing and impact of the transition and to report on the benefits achieved, including improvements in overall cost savings and the minimization of project-related risk.

These success factors can help guide companies in their journey toward best practices in capital procurement, but they will deliver their full value only if they are accompanied by the active management of key stakeholder relationships and an effective process for working across functions. Many companies have demonstrated that procurement isn’t just another administrative process; it is a driver of value. The positive results that these companies have achieved have set a high bar for others to follow if they wish to reap the full benefits of a best-practice capital-procurement function.