How do successful companies make the right choices in order to create attractive shareholder value? There is no one simple or universal formula. Companies as different as the North American retailer of high-end yoga and exercise clothes Lululemon Athletica, the Korean automaker Hyundai Motor Company, and the U.S. industrial supplier W.W. Grainger all delivered shareholder returns over the past five years that were strong enough to earn them a spot in our top-ten rankings in their respective industries. But they illustrate the diversity of company starting positions, and each achieved superior performance following quite different paths.

In last year’s Value Creators report, we introduced the idea of value patterns—distinctive company starting positions that cut across industry boundaries and shape the range and types of strategic moves most likely to create value. This year, we use the stories of these three quite different companies to explore the wide range of contexts in which leaders must find strategies for value—and how they can use the value patterns concept to unlock new sources of value.

Four Factors Underlying Value Patterns

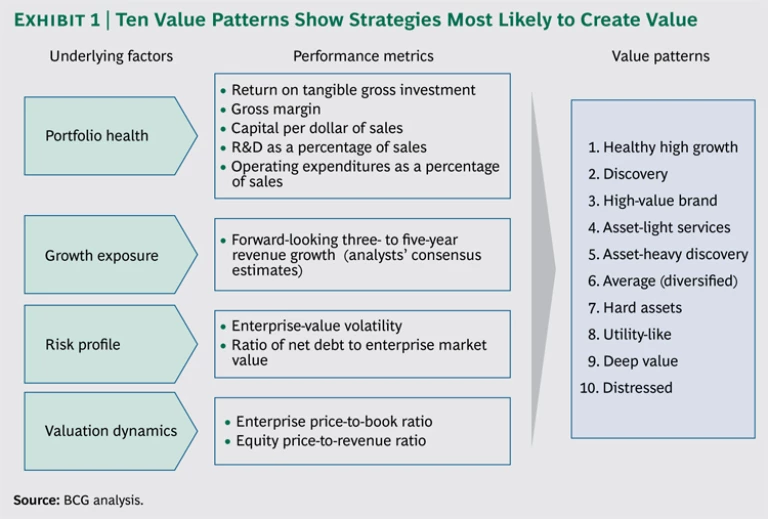

In recent years, BCG has been conducting a major proprietary research effort to analyze the quantitative factors that define a company’s starting position, as seen from an investor’s point of view. Our research has focused on four underlying factors that define the context for any company’s investment thesis: the health of its portfolio, the degree and quality of its growth exposure, the nature of the risks it faces, and the expectations of its investors, as expressed by the company’s valuation. Let’s consider each of these factors in turn.

Portfolio Health. Although delivering returns that are above the cost of capital has long been a fundamental principle of value management, it is striking how many executives still think of value creation in terms of earnings, margins, or growth rates. As long as earnings are growing, these executives think they are creating value. But an earnings- or profit-growth agenda is not necessarily a value agenda. More than one-third of the $8 trillion of invested capital in the S&P 1500 does not earn the cost of capital. A business with a low return on invested capital has yet to earn the right to grow. Therefore, the first question any senior executive team must ask itself is: Where do we enjoy competitive advantage in our business that can drive attractive returns on invested capital?

Growth Exposure. For market segments and positions with attractive returns, the next challenge is to find attractive growth exposure. Although the vast majority of companies are expected to grow at modest rates, most companies aspire to break out from the pack and deliver above-average growth. In doing so, however, the challenge is not simply to grow—for growth can create no value and, in some cases, can even destroy value. The key question is: How much growth exposure do we have, and how can we find profitable and sustainable growth?

Risk Profile. Highly leveraged, turbulent, or fast-changing businesses require different actions to defend and increase value. Debt leverage is highly visible because companies with stressed balance sheets have weak credit statistics and ratings. Companies with too much debt must focus on restructuring and liquidity. Businesses with significant commercial risk—those facing turbulent markets, rapid competitive shifts, or unusually high uncertainty on key business drivers—typically have volatile market values because investors are not sure whether today’s earnings will be around tomorrow. For some companies, the degree and types of risk will be the dominant value-creation issue they face. Investors will want to know how the company intends to protect itself against a significant deterioration in the franchise value of the business. So executives must ask: What are our key risks and how should we manage them?

Investor Expectations and Valuation. Most companies most of the time trade in a range that is consistent with their fundamentals and their future prospects. But sometimes, companies find themselves with a valuation that is considerably outside this range—with implications for future value creation that have to be managed. An unusually low valuation can be a tempting target for activist investors and threaten the breakup of the company. And while everyone likes a high stock price, too high a valuation can seriously penalize a company’s future TSR potential. The final question in formulating an investment thesis is: What expectations do our investors have, and does our valuation match our outlook?

Understanding a company’s profile along these four dimensions is a critical first step in developing a sound investment thesis to guide strategic priorities. But depending on a company’s starting point, any one of these factors may carry a special weight. BCG’s research on roughly 6,000 companies in 60 countries has identified ten distinctive value patterns that combine these four factors—portfolio health, growth exposure, risk profile, and valuation dynamics—in different ways. (See Exhibit 1.)

Lululemon: Navigating the High Wire of High Growth

To get a sense of how value patterns work, consider the story of Lululemon Athletica, a North American specialty retailer with a leading brand selling premium yoga apparel to women. The company opened its first store 15 years ago in Vancouver, sharing space with a yoga studio. With well-designed and technically advanced products, an energizing in-store experience, and a strong focus on community development, Lululemon has created a powerful new brand.

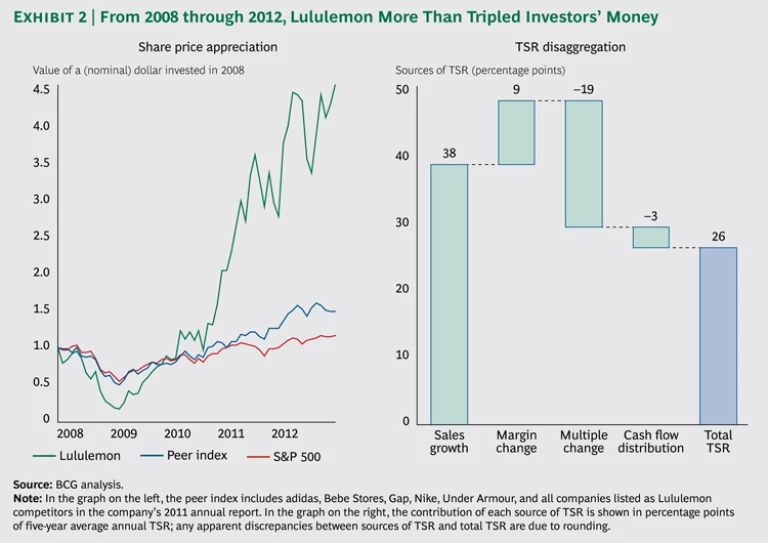

By 2008, the company had revenue of $275 million from 80 retail locations and was listed on the NASDAQ stock exchange. The company’s economics were very healthy, with gross margins of more than 50 percent and return on gross book capital of more than 40 percent. Investor expectations were also high—the company had a market value of $3.2 billion. Investors were valuing the company at almost 12 times sales and at more than 20 times enterprise book capital. Despite these high expectations, Lululemon was able to deliver an average annual TSR of 26.3 percent during the five-year period from 2008 through 2012, placing the company at the number five spot in this year’s global consumer durables and apparel industry ranking.

How did Lululemon more than triple its investors’ money over this five-year period? (See Exhibit 2.) In 2008, the company’s starting position fit what we call the healthy-high-growth value pattern. Companies in this position, which make up about 5 percent of the 6,000 companies in our global sample, are often pioneers that create new categories, brands, or business models. Recent examples include Amazon.com, Netflix, Green Mountain Coffee, and Intuitive Surgical.

Lululemon: Navigating the High Wire of High Growth

These companies have healthy business systems that earn extremely high operating returns—their median return on gross investment is 17 percent, more than double the global median of 8 percent. They also show growth potential. They are expected to scale their businesses up significantly, with a credible path to doubling sales and profits several times over a five- to ten-year time horizon. Because of these companies’ obvious strong prospects, investors have high expectations and value them at high multiples, often in the range of five to eight times enterprise book capital, as compared with the global average (1.7 times enterprise book capital). But healthy-high-growth businesses also face significant commercial risks: their high margins attract competition, their market values are volatile, and their high valuations create significant room for disappointment.

The primary value-creation priority for companies in a healthy-high-growth value pattern is to “beat the fade.” Every innovative high-growth business transitions or fades to maturity at some point and, as a result, shows a significant decline in valuation multiples along the way (often a more than 50 percent decline over five years). The healthy-high-growth companies that create superior shareholder value take longer to reach maturity and end up with a competitively stronger and sustainable end-state portfolio. Over the past five years, Lululemon has created value by pursuing three strategic themes typical of successful healthy-high-growth companies.

Execute successfully against the core growth opportunity. Since 2008, Lululemon has expanded rapidly, more than doubling its number of stores from 80 to 200 (within the context of roughly 350 potential North American locations). In the process, it has increased its revenues fivefold and its operating profit more than sevenfold. Lululemon also expanded from its initial focus on yoga apparel for women into adjacent segments. The company has added athletic clothes for running, biking, and swimming, as well as products for both men and children. And recently, it invested to expand its direct-to-consumer channel on the Internet; in 2012, the company’s online sales grew by 86 percent.

Maintain differentiation and demand stickiness. A common pitfall for healthy-high-growth companies is to pursue rapid growth at all costs and end up with a diluted, overextended franchise vulnerable to competitive inroads. The very success of healthy-high-growth companies makes them targets for new competitors. As Lululemon has grown on the back of the premium yoga craze, Nike, adidas, and others have aggressively pursued the same customers.

Lululemon was careful to preserve the quality of its revenue base by opening new locations in a disciplined way. It maintained close control of product distribution and the customer experience. It reinforced an exclusive, premium-brand image through technical product innovations. And it engaged customers emotionally by promoting an ecological, spiritual, and sexy lifestyle.

A critical factor in maintaining Lululemon’s premium position is the company’s innovative “community based” approach to building brand awareness and customer loyalty. The company’s target customer is a confident and healthy 25- to 35-year-old woman with no children, a career, and significant disposable income. In addition to its own stores and website, the company selectively distributes its products through high-end fitness clubs and yoga studios. The company is also an active user of social media to encourage the sense of an engaged community around its brand and customers. The resulting high levels of affiliation and trust that customers associate with Lululemon products function as a strong barrier against competitors.

Taken together, these moves have allowed Lululemon to deliver superior TSR through an extraordinary growth in revenues (responsible for 38 percentage points of TSR per year), coupled with a steady increase in operating profit margins (responsible for 9 percentage points of TSR per year). This strong performance more than offset a major decline in the company’s valuation multiple (responsible for a decline of 19 percentage points in TSR per year), as the company delivered on the high expectations embedded in its valuation at the beginning of the five-year period from 2008 through 2012.

Manage the risks of high growth. Maintaining the high performance expected of a healthy-high-growth company is difficult. Over a five-year period, 80 percent of the companies in this category either shift to more mature value patterns or lose their independence through a change in control. Lululemon has delivered strong shareholder value during the past five years, but, as a focused company with high expectations, it has experienced bumps along the way. The company started early 2008 with a stock price of $24 per share; in 2009, in the aftermath of the global financial crisis, it traded below $3 per share; and it subsequently reached a high of $78 per share in 2012.

Although Lululemon’s performance was very strong during the five years covered by this year’s Value Creators report, more recently it has not been so fortunate. In March 2013, the company was forced to recall approximately 17 percent of all women’s yoga pants sold in its stores because the product was unintentionally see-through. The flaw, caused by quality control issues in the company’s supply chain, caused the company’s earnings to take a hit of roughly $60 million and led to the resignation of its chief product officer. The long-term impact of this stumble remains to be seen—in particular, whether it will erode brand loyalty and provide an opening for Lululemon’s competitors to challenge the company’s valuable niche.

Hyundai’s “Deep Value” Turnaround

Sometimes the challenge facing a company is, in effect, to migrate from its current value pattern to one with more value-creation potential. To illustrate this situation, consider the recent history of Hyundai Motor Company. Founded in 1967, the company spent its first 35 or so years producing functional, low-priced cars. Although it dominates its domestic South Korean market, Hyundai made some major missteps when it first went abroad. The Excel, introduced in the U.S. in 1986, was cheap but also unreliable—establishing the Hyundai brand as a provider of low-cost, low-quality cars. Fifteen years later, in 2001, Hyundai was ranked only 32 out of 37 brands in J.D. Power’s annual study of new-vehicle quality.

Hyundai’s starting position in 2008 fit the value pattern we call deep value. Companies in this pattern are typically found in mature and often cyclical categories, with limited differentiation in what are often intensely competitive segments. With a median return on gross investment of only 4 percent, which is half that of our 6,000-company global sample, these companies do not earn the cost of their capital. And their lack of competitive differentiation means they usually have weak gross margins (a median of 18 percent, again, half the global sample median). Not surprisingly, they also have low valuations, trading at about 60 cents per dollar of enterprise book value.

Nevertheless, deep-value companies can create substantial shareholder value—but only if they reposition, restructure, and reinvest strategically to bring about a radical improvement in their value proposition. This is precisely what Hyundai has done—creating a much stronger business (with higher sales and margins, greater return on capital, and lower leverage) and, consequently, driving a massive increase in equity value.

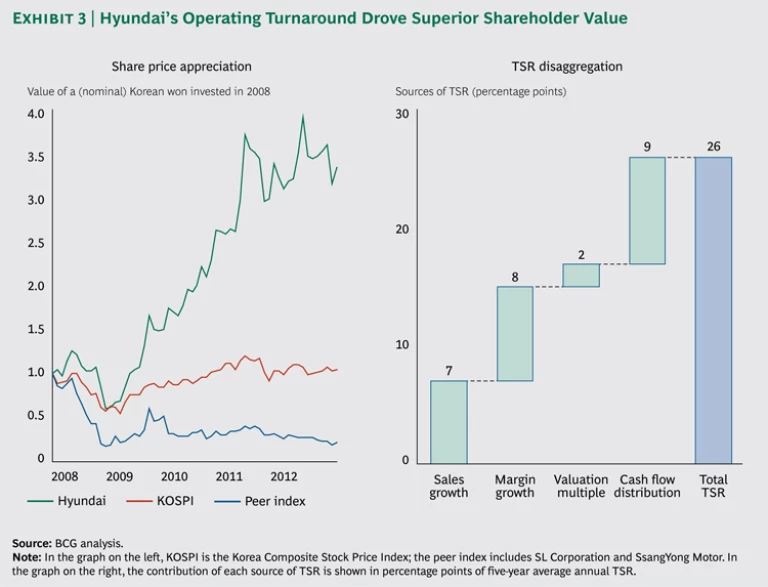

In the past decade, Hyundai has undergone a total transformation under the leadership of company chairman Mong-Koo Chung (who took over in 1999 from his father and company founder Ju-Yung Chung). The company has cultivated a mindset of ambition, boldness, and impatience to become a global leader. Hyundai Motor America’s CEO summarized that culture this way in a 2010 article in Fortune: “We set targets before we know how to get there. And we are the hardest-working company on the planet.” As a result of its ongoing transformation, Hyundai has become the fastest-growing automaker in the world. In the period from 2008 through 2012, Hyundai reaped the rewards of this operating turnaround in shareholder value creation, delivering an average annual TSR of 26.4 percent, enough to put the company at the number six spot in our global automotive OEM rankings. (See Exhibit 3.)

Hyundai’s “Deep Value” Turnaround

How did Hyundai create this $35 billion increase in shareholder value? Through a strategic focus on three specific “unlocks” that fit the company’s 2008 deep-value starting position.

Invest strategically to drive a more competitive offer. Hyundai’s recent strong performance reflects the company’s long-term pursuit of a more competitive global product range that delivers higher quality and better technology—at very affordable prices. The company inaugurated a major quality-improvement initiative that included steps such as building a pilot production line in its product-development R&D center to test the manufacturability of new models while they were still in development. By 2009, Hyundai had improved its ranking in J.D. Power’s annual quality study from number 32 to number 4—displacing Toyota as the highest-ranked mass-market brand in the world, behind only luxury brands Lexus, Porsche, and Cadillac.

Hyundai also invested heavily to develop a new group of vehicles with quality and technology equal to its high-end competitors but at a substantially lower price point. For example, in 2008, the company developed its first six-speed transmission and, in 2009, its own direct-injection engine—a development that has won it a place on the list of the world’s top-ten automotive engines. And instead of selling the same models in every market and region, Hyundai has developed different models designed specifically for the needs of its different target markets.

These investments have paid off in both increased sales and a transformation in the reputation of the Hyundai brand. For example, the Hyundai Genesis, a step up from the midsize Sonata, was introduced to the U.S. market in 2008; in 2009, it was selected as North American Car of the Year. In 2010, the company introduced the Equus, designed to compete with top-of-the-line models from Mercedes, BMW, and Audi. These new models have led to greatly expanded sales, not only in the U.S. but also in China, where Hyundai is one of the top foreign automakers, by sales. Between 2008 and 2012, the company’s profits tripled.

Improve productivity and margins. In addition to introducing new products, Hyundai made significant investments to lower its manufacturing and supply-chain costs—resulting in expanding margins. Although the company manages the world’s largest integrated auto manufacturing site in Ulsan, South Korea, it has also invested in significant capacity close to global customers, with seven overseas manufacturing plants located in Brazil, China, the Czech Republic, India, Russia, Turkey, and the U.S. Today, roughly 60 percent of Hyundai’s production takes place overseas.

Significantly reduce risk. In 2008, Hyundai’s balance sheet was relatively weak. The company had significant debt leverage, with a BBB– credit rating and about 70 cents of net debt per dollar of enterprise value. As the company generated successful new products and substantially more free cash flow, it was able to deploy a portion of that cash flow to pay down its debt and thus reduce risk. By 2012, the company had cut its debt-to-enterprise value by more than half (to 31 percent), winning an upgrade to an A credit rating.

Hyundai’s value-creation performance over the past five years has not only been strong but also remarkably balanced. Contributions from revenue growth accounted for about 7 percentage points of average annual TSR; margin improvement was responsible for about 8 percentage points; growth in the company’s valuation multiple provided an additional 2 percentage points; cash flow returned directly to investors added 1 percentage point; and cash flow returned to debt holders to pay down debt contributed 8 percentage points. If Hyundai can continue along its current trajectory, it will be well on the way to establishing itself in the value pattern that we term high-value brand.

Grainger: Maintaining the Strengths of a High-Value Brand

The companies in the high-value-brand value pattern usually enjoy leadership positions in mature but healthy categories. Such companies make up about one-fifth of our 6,000-company global sample and are among the healthiest and strongest businesses in the market. They typically enjoy powerful competitive advantages and have a limited concentration of earning power in any single technology, patent, or product. They derive advantage from scale, from brands, from capabilities, from strategic control of scarce resources, or from a combination of these strengths. As a result, they enjoy high and relatively stable gross margins (a median of 47 percent compared with the global median of 36 percent), moderate capital intensity (requiring roughly 50 cents in capital to generate a dollar in revenue), and a return on gross investment well above the cost of capital.

And yet, not all high-value-brand companies are necessarily strong value creators. Over a five-year holding period, approximately one-third of companies that start in this value pattern deteriorate in performance significantly—enough to migrate down to other value patterns with lower margins, lower returns on capital, and lower average valuations. To avoid such a negative outcome, high-value-brand companies have four distinct priorities for unlocking new value:

- They need to protect and grow the category—and, in particular, defend themselves against any broad long-term shifts that could fundamentally reshape their core markets.

- They must avoid complacency—especially in the form of strategies that milk the business in order to meet quarterly earnings-per-share targets at the price of eroding long-term competitiveness.

- They also need to avoid complexity and low-quality growth. The high valuations for these companies (unlike those for healthy-high-growth companies) do not reflect investor expectations of high revenue growth; rather, they are primarily supported by high gross margins and high return on capital. We estimate that 1 percentage point of sustained additional gross margin at these companies is worth three to four times more in market value than 1 percentage point of additional future revenue growth.

- Finally, because high-value-brand companies invariably generate far more cash than they can usefully invest in growing the business, these companies have to carefully allocate excess cash. How they deploy that cash can have a major impact on their TSR performance.

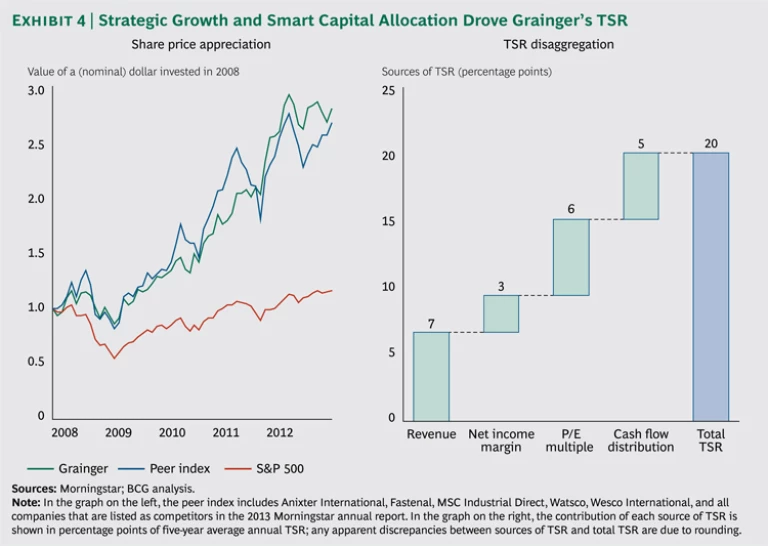

For an example of a company in this year’s top-ten rankings that successfully met these challenges, consider the case of W.W. Grainger. With 2012 sales of $9 billion, Grainger is North America’s leading supplier of so-called maintenance, repair, and operating (MRO) products—everything from industrial motors to janitorial supplies purchased by business facilities. In 2008, Grainger was a well-positioned competitor in its sector with high gross margins (in the neighborhood of 45 percent) and a healthy enterprise value of more than two times the company’s gross investment. At the same time, however, the company faced threats to its core business, both from the effect of the oncoming economic downturn on customer demand and from increased competition from new players in the MRO market. Despite these challenges, Grainger did three things that allowed it to maintain its strong position and deliver an average annual TSR of 20.4 percent during the five-year period from 2008 through 2012—making it the number seven value creator in our machinery sector. (See Exhibit 4.)

Hyundai’s “Deep Value” Turnaround

How did Hyundai create this $35 billion increase in shareholder value? Through a strategic focus on three specific “unlocks” that fit the company’s 2008 deep-value starting position.

Invest strategically to drive a more competitive offer. Hyundai’s recent strong performance reflects the company’s long-term pursuit of a more competitive global product range that delivers higher quality and better technology—at very affordable prices. The company inaugurated a major quality-improvement initiative that included steps such as building a pilot production line in its product-development R&D center to test the manufacturability of new models while they were still in development. By 2009, Hyundai had improved its ranking in J.D. Power’s annual quality study from number 32 to number 4—displacing Toyota as the highest-ranked mass-market brand in the world, behind only luxury brands Lexus, Porsche, and Cadillac.

Hyundai also invested heavily to develop a new group of vehicles with quality and technology equal to its high-end competitors but at a substantially lower price point. For example, in 2008, the company developed its first six-speed transmission and, in 2009, its own direct-injection engine—a development that has won it a place on the list of the world’s top-ten automotive engines. And instead of selling the same models in every market and region, Hyundai has developed different models designed specifically for the needs of its different target markets.

These investments have paid off in both increased sales and a transformation in the reputation of the Hyundai brand. For example, the Hyundai Genesis, a step up from the midsize Sonata, was introduced to the U.S. market in 2008; in 2009, it was selected as North American Car of the Year. In 2010, the company introduced the Equus, designed to compete with top-of-the-line models from Mercedes, BMW, and Audi. These new models have led to greatly expanded sales, not only in the U.S. but also in China, where Hyundai is one of the top foreign automakers, by sales. Between 2008 and 2012, the company’s profits tripled.

Improve productivity and margins. In addition to introducing new products, Hyundai made significant investments to lower its manufacturing and supply-chain costs—resulting in expanding margins. Although the company manages the world’s largest integrated auto manufacturing site in Ulsan, South Korea, it has also invested in significant capacity close to global customers, with seven overseas manufacturing plants located in Brazil, China, the Czech Republic, India, Russia, Turkey, and the U.S. Today, roughly 60 percent of Hyundai’s production takes place overseas.

Significantly reduce risk. In 2008, Hyundai’s balance sheet was relatively weak. The company had significant debt leverage, with a BBB– credit rating and about 70 cents of net debt per dollar of enterprise value. As the company generated successful new products and substantially more free cash flow, it was able to deploy a portion of that cash flow to pay down its debt and thus reduce risk. By 2012, the company had cut its debt-to-enterprise value by more than half (to 31 percent), winning an upgrade to an A credit rating.

Hyundai’s value-creation performance over the past five years has not only been strong but also remarkably balanced. Contributions from revenue growth accounted for about 7 percentage points of average annual TSR; margin improvement was responsible for about 8 percentage points; growth in the company’s valuation multiple provided an additional 2 percentage points; cash flow returned directly to investors added 1 percentage point; and cash flow returned to debt holders to pay down debt contributed 8 percentage points. If Hyundai can continue along its current trajectory, it will be well on the way to establishing itself in the value pattern that we term high-value brand.

Grainger: Maintaining the Strengths of a High-Value Brand

Reinvest in a winning business model. As the highly fragmented MRO market continues to evolve, several large players are attacking the space from different legacy positions and business models. Fastenal, Amazon.com, Home Depot, McMaster-Carr, MSC Industrial Direct, and many other companies can compete with Grainger in different ways— depending on the product, customer, occasion, and geography. This diversity of customer options creates a strong need for Grainger to be clear about precisely how it will create sustained advantage versus the competition.

In response, the company’s strategy has been to position itself as a one-stop shop that is able to supply the full range of a customer’s MRO needs. It has invested significantly in broadening its product offering (which now includes products from more than 3,500 suppliers), expanding its sales-force presence in key markets (both in the U.S. and abroad), and developing a new on-site client account management system. One indicator that this strategy has been working is that the company’s growth in same-customer sales has nearly tripled.

Pursue modest but high-quality growth. Grainger also executed a careful growth strategy that focused on maintaining its already high margins. The company reduced costs by improving network capacity and productivity and by adding operating capacity in strategic locations in the U.S., Canada, and Japan. The company also expanded into the highly fragmented MRO sectors in emerging markets, through both organic investment and acquisitions. Finally, its online initiatives have greatly improved the ease with which customers find, buy, and manage their inventory online—so much so that e-commerce was Grainger’s fastest-growing channel in 2012, accounting for more than 30 percent of total company sales.

Ensure disciplined capital allocation. In some respects, however, the most interesting part of the Grainger story may be the strategic moves the company didn’t make. Although the company has made some strategic acquisitions to fill out its footprint, it has been careful not to tie up cash in “bet the company” or diversifying M&A bets. In 2012, for example, Grainger generated over $800 million in free cash flow. The company reinvested just under a third of that cash to fund its capital expenditures and two small acquisitions. The lion’s share (over two-thirds) was returned to shareholders in the form of stock buybacks and dividends. And Grainger has committed to a predictable return of cash, more than doubling the dividend (from $1.34 to $3.06) between 2007 and 2012.

A careful growth strategy with smart capital-allocation decisions allowed Grainger to deliver its superior TSR through a balanced combination of revenue growth (responsible for 7 percentage points of average annual TSR), margin expansion (responsible for 5 percentage points), improvements in the company’s valuation multiple (responsible for 4 percentage points), and free-cash-flow yield (responsible for an additional 4 percentage points).

For more insights coming out of our research on value patterns, see “More Facts About Value Patterns.”

More Facts About Value Patterns

Here are some additional insights about value patterns that are emerging from BCG’s research.

-

Value patterns cut across industry boundaries. One finds companies from quite different industries sharing the same value pattern. For example, medical technology, machinery, and building materials don’t have much in common as industrial sectors. And yet, the top value creator in each sector—Elekta, a Swedish provider of automated clinical solutions for cancer and neurological diseases; TransDigm, a U.S. aircraft components supplier; and China Fortune Land Development, a developer of industrial parks—is a healthy-high-growth company, which means that these three companies face similar value-creation challenges and priorities.

-

Companies within a single industry may have quite different value patterns. In addition to healthy-high-growth companies like Elekta, for example, the medical technology top ten also contains companies in the discovery (U.S. heart-valve maker Edwards Lifesciences at number three), high-value brand (Italian diagnostic-equipment maker DiaSorin at number five), and asset-heavy discovery (German medical-technology solutions supplier Carl Zeiss Meditec at number eight) value patterns. Although they are in the same industry, these companies face different priorities and tradeoffs for value creation.

-

Companies in the discovery value pattern are usually healthy technology innovators with high R&D expenditures, gross margins, and returns. However, such businesses are also risky and show significant volatility owing to unstable segment boundaries and rapid product or technology obsolescence. Unless a discovery company can keep replenishing its commercial base with fresh and relevant innovation, it is unlikely to sustain attractive levels of value creation.

-

Companies in the asset-light services value pattern are usually intermediaries—aggregators of products and services such as large distribution systems. They generate healthy returns because of their low capital intensity and ability to expand sales with little capital investment. But they are highly sensitive to incremental changes in margins and must avoid growth that increases asset intensity, dilutes margins, or exacerbates execution risk.

-

Companies in the hard assets value pattern are mature, healthy, but modest-return businesses with extremely high capital intensity. Success in this value pattern depends on scrupulous management of the asset base—in particular, maintaining a competitive capacity base through both operational effectiveness and well-conceived, well-executed capacity adds and closures. A long-term horizon and the ability to manage effectively through up-cycles and down-cycles can create substantial shareholder value.

-

About one in four companies in our 6,000-company global sample has a starting position that we call average (diversified). These companies have characteristics close to the average company in our sample. Instead of being able to focus on two or three clear issues in their investment thesis, they have to take a more balanced approach.