The following article originally appeared in Industrial Minerals .

Ask inhabitants of the Juruti district of Brazil what benefits have been brought by the bauxite mining started in 2009 by Alcoa, and they can point to a new school and police station. These are among 21 projects backed by the Sustainable Juruti Fund, created by Alcoa but run by a local development council with representatives from industry, government, and nongovernmental organizations (NGOs).

Set up as a public arena for dialogue and debate, and for directing development for a region new to large-scale mining, the council also supports eight technical committees focusing on issues such as health and the environment.

This open, collaborative, and trust-building approach between developer and host community is advocated in a recent report, A Framework for Advancing Responsible Mineral Development , which captured the findings of the second phase of the World Economic Forum’s Responsible Mineral Development Initiative (RMDI). The premise of the report, which was produced in collaboration with The Boston Consulting Group, is that while mining is a key driver of global economic growth with the potential to transform economies and societies, it has not always fulfilled that potential.

The report is based on two years of research, analysis, and consultation with more than 400 stakeholders worldwide—not only the companies, but national and local governments, NGOs, communities affected by mineral development, and independent experts.

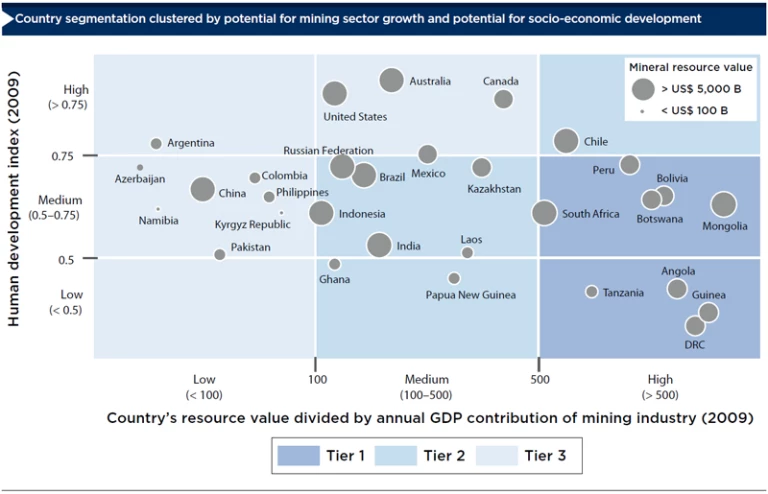

The RMDI analyzed the 30 largest mining economies. By assessing each country’s potential for mining sector growth and socioeconomic development, it isolated a group of nine high-potential countries: Angola, Bolivia, Botswana, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Guinea, Mongolia, Peru, South Africa, and Tanzania. The report estimates that these countries hold 28 percent of the resources in the top 30 countries but attract only 12 percent of the investments. It suggests that this may reflect either reluctance to welcome mining or companies’ wariness of local conditions.

So, what are the barriers to unlocking this significant potential for growth and development? And what are the building blocks for success?

The Challenges

The size and complexity of mining projects, and the huge variety of contexts in which they take place, make any search for silver-bullet answers futile.

A Framework for Advancing Responsible Mineral Development does not claim to have all the answers. Instead, it offers a framework for dealing with the most significant challenges facing the industry.

The first stage for the RMDI identified the challenges. Stakeholders perceived four major obstacles:

- Limited expertise and institutional capacity in government, civil society, and companies

- The inadequate inclusion of stakeholders in decision-making processes

- Opaque negotiation and development processes, with inadequate sharing of information

- Incomplete compliance, monitoring, and dispute-resolution procedures

The WEF and BCG found that the key demand on all sides was for trust and stability. Companies making large, long-term investments—being wary of resource nationalism and arbitrary law changes—need to be sure they are working in a stable environment. In turn, governments and communities have to feel that they will receive an equitable share of the benefits from mining in return for the impact that development has on their society and environment. All of this makes transparency and good communication essential. In their absence, distrust and misunderstanding will flourish.

The Framework

The RMDI’s second stage was devoted to devising and developing a framework for advancing responsible mineral development. This consists of six building blocks. Each is intended to operate across the length of a mining project, creating trust and stability and minimizing the likelihood of conflict while also providing a means of resolving disputes. The building blocks are supported by examples of possible actions, case studies, and initiatives.

The building blocks include the following:

- Progressive capacity building and knowledge sharing among all stakeholders

- A shared understanding of the benefits, costs, risks, and responsibilities related to mineral development

- Collaborative processes for stakeholder engagement throughout the lifecycle of mining projects

- Transparent processes and arrangements

- Thorough compliance, monitoring, and enforcement of commitments

- Early and comprehensive dispute management

The WEF and BCG’s extensive consultation showed that capacity limitations across all stakeholder groups are recognized as a significant problem. They can, for example, limit the ability of governments to negotiate effectively with companies at the beginning of a project. This can lead to unequal agreements and, later, destabilizing demands for them to be reopened. Having better equipped, better informed stakeholders is beneficial on all sides.

One of the most effective ways to address this problem is through the creation of a global repository of good-practice guidance. The World Bank’s Extractive Industries Source Book, launched in 2011 and run by the University of Dundee, is an excellent example.

There is also a need for tailored training and development programs for governments and other participants. This is being done under the Africa Mining Vision, founded by the African Union in 2009 as a capacity-building institution for mining companies. An example already in action is the Royal Bafokeng Nation in South Africa, which makes use of its income from platinum mining to fund tertiary education for community leaders.

Shared Understanding

A major source of distrust and instability is disagreement on, or ignorance of, the precise costs, benefits, risks, and responsibilities related to any mining development. This creates fear that one party will get all the benefits from mining, while others carry the costs and risks. It also leads to a lack of clarity over the assignment of responsibilities.

This problem can be addressed by commissioning rigorous and collaborative studies of the economic and social costs and benefits. These provide objective evidence on which to base discussions, negotiations, and partnerships.

One highly effective template for such studies is Mining: Partnerships for Development, a toolkit provided by the International Council on Mining and Metals and currently being applied in Brazil—the tenth country in which it has been used since 2006. When applied to Laos, it established that mining makes a bigger contribution to the national economy than hydroelectric power, surprising even the country’s government. A privately funded initiative, Newmont’s study of Ghana has won general acceptance because it was run independently, used publicly available data, and took full account of community and other stakeholder viewpoints.

Collaborative Processes

Sustainable, responsible development, based on trust and stability, will only be achieved if there is somewhere for stakeholders to meet for an open, honest, and robust dialogue. This sort of engagement should start at the earliest stage of any project and be maintained throughout its lifecycle. These dialogue platforms need to operate at the national, regional, or local levels, with connections among the levels.

Since 2007, the Canada-based Devonshire Initiative has provided a neutral international venue for contact between mining companies and NGOs concerned with developing economies. At a national level, Mongolia has, since 2006, brought together government, companies, and NGOs to discuss its high-potential, but contentious, minerals sector. Juruti in Brazil provides an example of a local development council, while the agreement to mine gold at Eleonore in Canada specifically commits Goldcorp to actively involve the local Cree Nation population—for example, in cowriting the environmental- and social-impact assessment—throughout the lifecycle of the project.

Transparent Processes

Making information and agreements available, together with facilitating open negotiations, will enhance trust among stakeholders. Trust can be further underpinned by an independent audit of data, which requires the publication of mining contracts and the tax, royalty, and revenue data associated with them. The Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative (EITI) provides a system for monitoring and reconciling payments, which has been fully adopted by 11 countries—with Ghana going well beyond EITI minimums by publishing information on a project-by-project basis; a further 23 countries are at the candidate stage.

Liberia, the second country to become EITI-compliant, has published all mining agreements and tax payments since 2008 and has established its own EITI. Rio Tinto has supported EITI since its launch in 2002; in 2012, the company, for the second time, published the full details of taxes paid to governments in all countries where it generates revenue.

With most attention paid to agreements, much less notice is taken of procurement, compliance, and the enforcement of contracts, but these are also highly important. Rigorous, universally understood standards for awarding contracts can be supplemented by monitoring for compliance and performance and spelling out guidelines for establishing whether parties are keeping promises.

These processes will work best if they are established at an early stage, with the full involvement of all stakeholders. There is then great transparency of who has agreed to what, which parties have which roles, what the processes are, and how they will be enforced.

The World Bank Institute (WBI) has worked with its Africa region to create a contract-monitoring initiative in the area. It already includes six countries and is expanding into Francophone Africa. In Ghana, the WBI helped create a contract-monitoring coalition of stakeholders, which campaigned successfully to get the issue onto the agenda of the Public Accounts Committee and Auditor General.

Dispute Management

Even with full transparency and the best possible compliance mechanisms, differences in interests and priorities will inevitably lead to disagreements. By accepting this reality, and planning for it, stakeholders can minimize the likelihood of a conflict escalating to the point that it seriously disrupts projects.

A wide range of conflict-management mechanisms is available. What matters is that stakeholders select one appropriate to local circumstances and that it is in place and fully understood by all parties as early as possible in the process. Discussion of how to manage disputes can, in and of itself, help identify potential conflicts early on.

The Harvard Kennedy School’s “Rights-Compatible Grievance Mechanism” offers companies a flexible toolkit, based on seven key principles and offering 24 practical guidance points.

Among leading companies, Anglo-American has pioneered a standardized complaints and grievance procedure for employees, including electronic tracking and monitoring, while the Canadian government’s Office of the Extractive Sector Corporate Social Responsibility counselor was created in 2010 to promote responsible practices and resolve disputes for Canadian mining and oil and gas companies operating overseas.

Stakeholders polled about the actions put forward under the six building blocks in this report were very positive, with nearly two-thirds of a sample of 145 from 33 different countries saying they were “very” or “extremely” helpful. Overall, support was greatest for training and development programs and the creation of national dialogue platforms.

Public sector respondents, who were the most enthusiastic about the proposals as a whole, rated those two actions most important, as did those from civil society and NGOs, who also highlighted the need for compliance monitoring.

Company representatives also strongly favored national dialogue platforms but placed their strongest emphasis on conducting rigorous socioeconomic studies.

The RMDI process also included an examination of Mineral Development Agreements (MDAs), the agreements between companies and governments under which mining is conducted in many countries, including 23 of the 30 largest mining economies. MDAs have been widely criticized, with particular concern about asymmetrical bargaining, lack of transparency, and complexity. Options discussed included devising a model agreement or replacing MDAs with regulatory systems based on legislation. Neither was felt to be practical.

MDAs are likeliest to be demanded by investors in countries with limited government capacity, given that the best legislation is ineffective unless backed by honest policing and an effective court system.

With MDAs almost certain to remain a feature of the mining environment in the immediate and midterm future, some stakeholders argue that they have the potential to act as a guarantee to investors and to define the roles and responsibilities of different parties. In the longer term, the aim would be, through the six building blocks, to create environments of trust in which investors are less likely to demand MDAs.

What Next?

Mining companies are advised to prioritize stakeholder engagement and understand host communities, and are reminded that a reputation for responsible development is an increasingly valuable asset.

Policymakers are advised to aim for robust regulation, identify gaps in their own capacity and the means of closing them, and make use of tools and partnerships available. They are reminded that where regulation is lacking, improved transparency can bring immense benefits.

NGOs are advised to play a full and active part in partnerships and forums, bringing their local expertise to bear. They are reminded of their potential role as facilitators among local communities, industry, and government.

The hope of the RMDI is that the implementation of the six building blocks will, by creating trust and stability, address the problems unearthed through consultation with the industry’s various stakeholder groups, thus unlocking the potential for growth.

Contributors: Roland Haslehner, partner and managing director at The Boston Consulting Group, and Guido Battaglia and Jose Garcia, community managers, Mining & Metals, from The World Economic Forum.