To mark The Boston Consulting Group’s fiftieth anniversary, BCG’s Strategy Institute is taking a fresh look at some of BCG’s classic thinking on strategy and exploring its relevance to today’s business environment. This third in a planned series of articles examines time-based competition, a concept introduced by BCG in a series of Perspectives in 1987 and 1988 .

BCG CLASSICS REVISITED

- The Rule of Three and Four

- The Experience Curve

- The Growth Share Matrix

Nearly 25 years after the book’s publication in 1990, Apple CEO Tim Cook is known to give his colleagues copies of Competing Against Time: How Time-Based Competition Is Reshaping Global Markets, the seminal work by BCG’s George Stalk and Tom Hout. Why does the leader of one of the world’s most innovative companies consider it a still-worthwhile read?

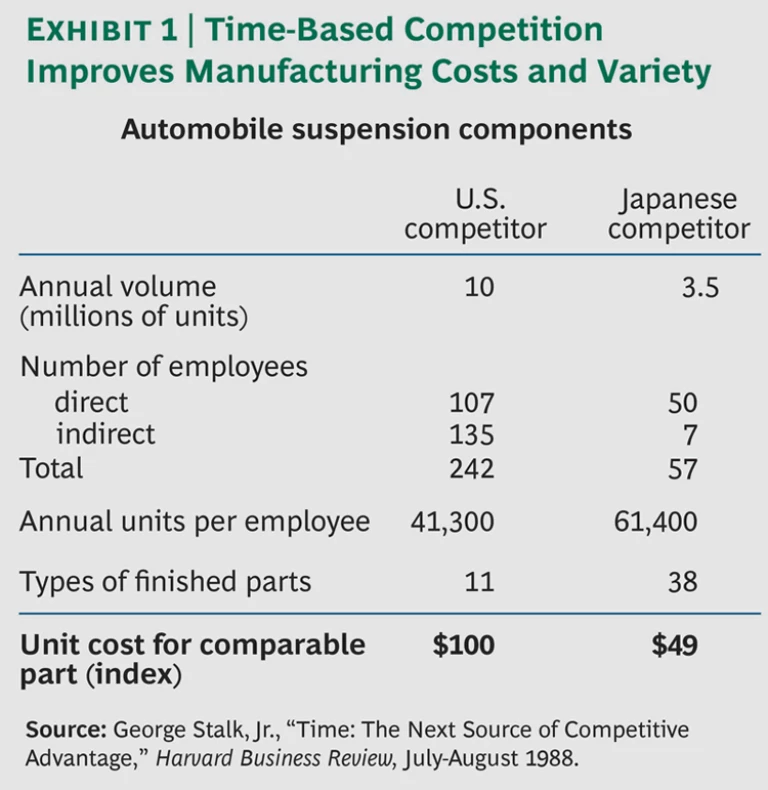

Traditionally, businesses strove to produce high-quality goods at the lowest possible cost. But Stalk and Hout taught the business world that the added element of speed was ultimately the key to competitive advantage. Stalk had observed Japanese companies that were not scale leaders in their industries reaping advantage by shortening their product-development cycles and factory-process times—essentially managing time the way that most businesses managed costs, quality, and inventory. This “flexible manufacturing” approach also reduced variety-related costs at the companies. Consequently, despite their smaller size and volumes, these companies could produce fewer goods but with greater diversity and quality than their competitors—and do so at lower cost. (See Exhibit 1.)

The acceleration of cycle times not only allowed companies to remove waste from the process, it also provided a host of competitive benefits. By responding more quickly, companies enhanced their productivity and also gained favor with customers, thereby achieving higher market share. By embracing the principles of time-based competition (TBC), the businesses also reduced complexity and rework and increased transparency, allowing them to break the assumed tradeoff between cost and quality.

TBC’s impact on business thinking ultimately proved enormous, with companies across sectors embracing it and its popular derivative, process reengineering, to streamline and accelerate their operations. Sun Microsystems (acquired by Oracle in 2010) achieved market dominance by halving the time required to design and introduce engineering workstations. Honda gained ground by introducing 113 new models in the time it took its close competitor Yamaha to create 37. Jack Welch announced that GE’s core principles would be “speed, simplicity, and self-confidence.”

Zoom forward to today, when the pace of change seems faster than ever: technologies are evolving increasingly quickly, economic power is shifting to emerging markets, and many business models are becoming obsolete. As a result, an unprecedented number of long-standing incumbent companies seem to be questioning how they do business.

Companies are attempting to meet the demands of this time-compressed reality in both new and traditional ways. They are exploiting 3D printing, for example, to reduce the time it takes to produce prototypes; deploying automated factories to shrink change-over times; enabling greater customization and closer proximity to customers; and leveraging big data and analytics to make it easier to identify and act on opportunities.

Common to all of these efforts is the recognition of the growing primacy of speed. Words like “agility” are increasingly on the lips of CEOs. Says Jeremy Stoppelman, CEO of Yelp, “You have to be very nimble and very open-minded. Your success is going to be very dependent on how you adapt.” It’s a view that extends well beyond the big-tech arena. As Mitchell Modell, CEO of Modell’s Sporting Goods, observes, “The big never eat the small—the fast eat the slow.”

So, are we headed back to the future? Is Tim Cook right? Is it time to dust off the BCG classic and re-reengineer our core processes? The answer to all three questions is yes—but with several important qualifiers.

Without a doubt, the pace of change is now faster than ever. Many businesses have evolved into essentially information businesses, and many more are critically dependent upon increasingly complex signals and information.

Companies now, therefore, need to act at the “speed of data.” This is a tough quantitative challenge, requiring new technologies and techniques to bridge gaps between the intrinsic speed and flexibility of data on one hand, and people, organizations, and physical assets on the other. It is also a qualitative challenge, requiring many companies to rethink their business model.

UPS, a package delivery firm, may not seem like a digital company. But living up to its “Moving at the Speed of Business” tagline requires sophisticated and dynamic integration, analysis, and aggressive data management. UPS’s front-line employees use data to meet performance objectives. Truck drivers, for example, use route-optimization algorithms to decide whether to save a mile of driving or to deliver a package 15 minutes early. To avoid overwhelming employees, the company refines the display of information; to make workers more comfortable with on-the-job analytics, it utilizes familiar platforms, such as smartphones. UPS also prioritizes continuous improvement to become faster still: it is building real-time, adaptive analytics into the next version of its logistics software, for instance.

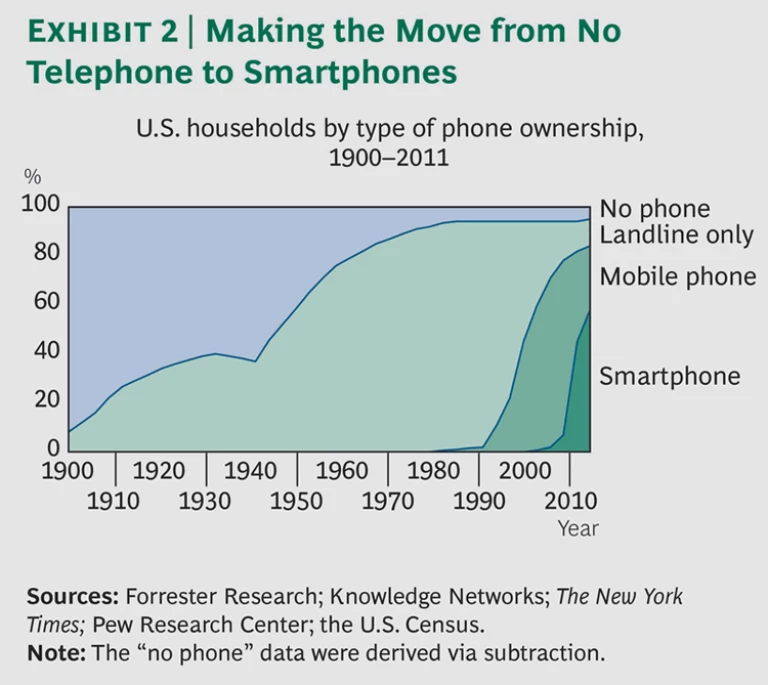

Whereas TBC was about doing a predictable set of activities faster, companies now also need to be able to learn how to do new things faster and more effectively. Agility is insufficient—companies now also need to be adaptive. In today’s era of accelerated change, new products, technologies, and business models can arise before companies have had a chance to fully optimize existing ones. Exhibit 2 shows how telephone technology illustrates this phenomenon at work.

Alibaba, China’s dominant retailer, exemplifies “TBC 2.0” and its virtuous cycle of data, speed, learning, innovation, and growth. Every day, Alibaba’s three server centers process more than a petabyte of data—the equivalent of three times the storage space needed for all the DNA information of the U.S. population. With that data firepower, Alibaba is driving an economic transformation in Chinese retailing, delivering more products faster and to more people via more, new, and different business models.

And with speed and data come learning and business model innovation. Via AliPay, Alibaba’s customers can now pay for online purchases and invest their savings, and businesses can obtain loans. Companies and governments can store data on Alibaba’s cloud-computing services; and other retailers, such as Haier and Nike, can set up online store fronts through Tmall.com, Alibaba’s business-to-consumer platform. Alibaba is using speed, information, and innovation to tap the burgeoning power of Chinese consumption by creating a single, truly nationwide market.

Today’s need not only for speed but also for adaptiveness should spur managers to shift their mindset about the imperatives necessary to survive and succeed in a TBC 2.0 world. For an increasing number of businesses, these imperatives include the following:

- Reconceiving your business as an information business

- Ensuring that your organization can respond at the speed of data

- Recognizing that the basis for competitive advantage has shifted from scale, position, and speed to adaptiveness

- Cultivating and measuring rapid learning

- Balancing the exploitation of existing opportunities and business models with the exploration of new ones

- Breaking free from yesterday’s successful business model

Time-based competition is more relevant than ever. Companies must now not only run faster but also adapt to keep up.