The distinction between the business and social sectors is becoming increasingly fluid. Corporations are seeking to more actively address the challenges faced by society, and they are leveraging their business expertise to do so. Social organizations are looking to companies in the private sector for the best practices, skills, and know-how needed to deliver greater value to populations in need and to increase operational efficiency.

New approaches such as impact investing, hybrid value chains, and shared value are emerging at the intersection of the social and business sectors, aiming to blend the best of both worlds.

Within this context, the concept of “social businesses”—companies with a primary objective of solving a social problem by applying business principles—has attracted particular attention. This report takes a closer look at social businesses from the perspective of a corporate organization. It highlights the value of the concept and how companies can develop a social business, with a special focus on the lessons and best practices needed to succeed.

While the report focuses on best practices for social businesses, many of the same lessons can be applied more broadly to other ventures at the intersection of the social and business sectors.

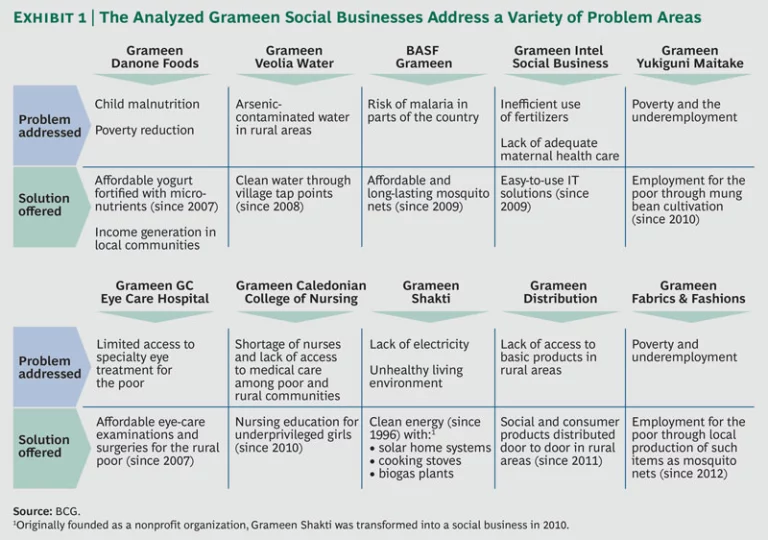

The report has been written in collaboration with Professor Muhammad Yunus, Nobel Peace Prize Laureate 2006, founder of the Grameen Bank, and early developer and implementer of the social business concept. It is based on an analysis of the lessons learned from ten social businesses that operate in Bangladesh today, each tackling a different social problem affecting people at the bottom of the economic pyramid. (See Exhibit 1.)

Many of the social businesses described are joint ventures between a Grameen organization and a multinational partner such as Danone, Intel, Veolia, and BASF. While several of the businesses are still in the learning stage, others—such as Grameen Shakti and Grameen GC Eye Care Hospital—have already achieved social impact, significant scale, and financial self-sufficiency.

The contents of this report are based on on-site workshops with managing directors and key staff, site visits and customer interviews, interviews with corporate partners, a web survey of the managing directors, and a detailed data analysis.

The Value of Social Business

Imagine a world in which electricity reaches even the most remote rural families in developing countries—those living far from today’s existing grid system—and provides them a means of working and studying late into the evenings. Imagine further that this electricity is green energy—solar home systems or biogas plants, for example. And imagine it were sold to the customers—most of whom live on less than $2 a day—for a price that makes the business financially sustainable and keeps it from depending on ongoing aid payments.

Impossible, you might say. And then you might travel to Bangladesh and come across Grameen Shakti, a social business that is thriving on just such a business model.

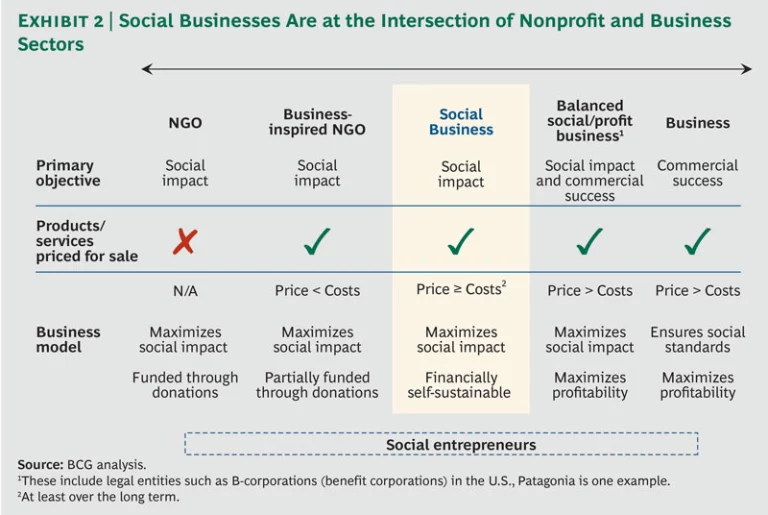

Many of the world’s most pressing social problems are so ingrained and widespread that they cannot be addressed solely by governments and traditional social-sector organizations. Solving these problems requires a variety of approaches from the private and public sectors alike. To this end, a wide range of new models is emerging along a spectrum that spans from nonprofits supported entirely by donations at one end to purely profit-oriented businesses at the other. By combining business principles with social objectives, these emerging models bridge the social and private sectors. Their various approaches can be distinguished both by the relative emphasis they place on social objectives versus profit objectives and by the degree to which they seek to generate their own revenues.

On this spectrum, social businesses fall somewhere between traditional NGOs and for-profit companies. (See Exhibit 2.) Like NGOs, their primary objective is to create social impact. At the same time, they operate like businesses and aim to generate sufficient revenues to at least cover their operating costs. Other emerging models, which lean further to the business side, try to weigh profit and social objectives equally; for instance, by aiming to generate at least a minimum profit while also pursuing a social impact goal. More toward the nonprofit side, business-inspired NGOs aim to generate at least some additional revenue by pricing their services, yet without the ambition to reach financial sustainability.

Although all these emerging models vary in the degree to which they combine profit targets with social targets, they all are built around the same basic belief: applying business principles to social problems can significantly increase efficiency, effectiveness, and financial sustainability. That’s why many of the lessons from social businesses presented in this report can also be applied to other emerging business models.

Exact definitions of “social business” vary.

Because social businesses don’t have as a goal increasing shareholder value or paying dividends, they are free to focus on the neediest, most underserved segments of the world’s populations—segments that traditionally fall outside the focus of profit-driven businesses. And because they price their products and services in a way that generates enough revenue to be self-sustaining in the long-term, these organizations do not depend on donations or other forms of external financial support to deliver their mission. Ultimately, social businesses maximize value delivered to society as opposed to the financial value delivered to shareholders.

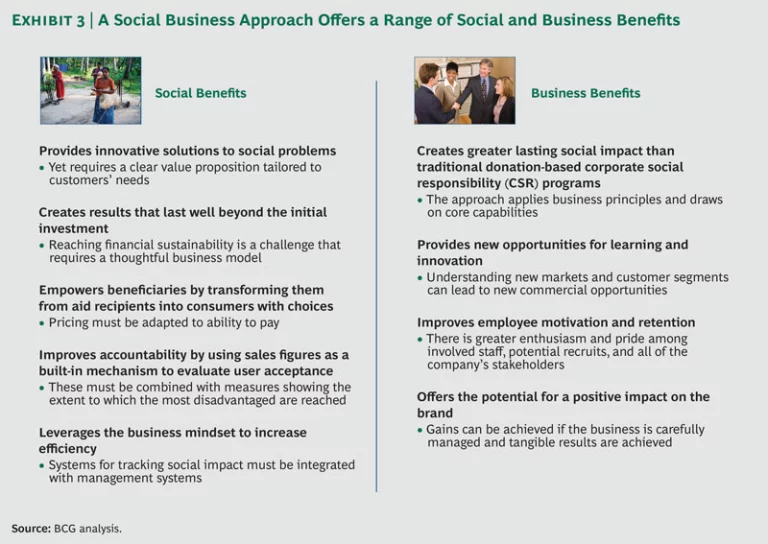

Today, social businesses exist in developing and developed countries alike. Although many are still in the early phases of development, some—like Grameen Shakti, which has revenues of about €72 million and more than 12,000 employees—demonstrate the potential scale of these ventures. Most important, however, are the social and business benefits that these organizations deliver. (See Exhibit 3.)

Social Benefits

With their focus on social impact and self-sustainability, social businesses can theoretically provide solutions to almost any social problem. As demonstrated by the range of social businesses analyzed in this study, such problems include fighting hunger and malnutrition, increasing the agricultural productivity of rural populations, offering poor rural households access to an environmentally friendly electricity supply, providing employment opportunities in areas where jobs are limited, and improving the health and life expectancy of local populations.

One example is Grameen GC Eye Care Hospital, which was founded in 2007 to tackle the prevalence of blindness and eye conditions such as farsightedness among the poorest populations in Bangladesh. The hospital provides low-cost eye care—including eye exams and cataract surgery—at three locations, and it extends its reach into the poorest, most rural areas through its traveling “eye camps.” By charging patients for its services based on their ability to pay, the hospital is affordable.

Although 20 percent of its 545,000 patients receive services at a very reduced price, the hospital still manages to break even due to its efficient operations and the income from higher-margin patients. To date, an estimated 2,500 blind patients have regained their eyesight as a result of the hospital’s services. In addition, the business has created 237 local jobs. Now that the model has proven its viability, efforts are under way to scale it up further, and two other eye-care hospitals are under construction.

Similarly, the other social businesses highlighted in this report create tangible social impact—the degree and extent of which depends on the business stage they are operating in. Grameen Danone Foods, for example, reaches more than 300,000 customers with fortified yogurt, and preliminary scientific studies point to the impact that the yogurt has on children’s growth rates and ability to concentrate.

BASF Grameen’s insecticide-treated mosquito nets (which are sourced from Grameen Fabrics & Fashions, another social business) protect more than 75,000 families from insect-borne diseases. Grameen Shakti’s solar home systems provide more than 1.2 million families with access to clean electricity, and Shakti’s improved cooking stoves create a cleaner living environment for roughly 700,000 households. Grameen Yukiguni Maitake has created 8,000 jobs in the cultivation of mung beans, providing new employment opportunities for farmers in rural Bangladesh. Furthermore, it recruited new employees as field supervisors and built a sorting factory. (For profiles of these social businesses, see “ Profiling Ten Grameen Social Businesses .”)

These solutions are designed to provide long-lasting, self-perpetuating benefits. Unlike traditional charitable organizations, which spend donated funds every year, a successful social business has self-sustainable operations because it is set up to recoup every dollar it invests. Social businesses also empower populations in need, transforming them from beneficiaries of charitable aid to independent consumers who have a choice and a stake in their own futures. In addition, by tracking sales figures and working with a business mindset, social businesses can achieve greater accountability and efficiency—further increasing the social return of every dollar invested.

Business Benefits

Unlike traditional, donation-based corporate social responsibility (CSR) activities, social businesses allow companies to directly use their skills, expertise, and business network to address a particular social problem. In this way, social business activities can be aligned with the core commercial business. If designed and managed effectively, this alignment not only generates lasting social impact but also can lead to tangible business benefits.

According to the corporations we surveyed, the most important business benefit that social businesses can provide is the potential for learning and innovation. All along the value chain, companies often find that the new products, operating models, marketing strategies, and distribution approaches aimed at reaching those most in need have a broader commercial application and can be a source of competitive advantage for the core business. For instance, Grameen Danone Foods set a goal of improving the health of children in Bangladesh by selling nutritious, affordable yogurt to local families. To maximize efficiency and create local employment opportunities, Grameen Danone Foods built the smallest plant that was technically possible—its capacity is below 4 percent of the typical capacity at a Danone factory in Europe. This production approach sharply reduces capital expenses and provides an innovative blueprint for small-scale production that Danone can leverage in other emerging markets. (For more details, see “ Jochen Ebert on Danone's Social (Business) Experiment .”)

When companies enter a new region, social businesses can also provide valuable insights into the legal, regulatory, and political environments. BASF Grameen’s primary social objective is to protect populations against insect-borne diseases, but the business also provides an opportunity to learn more about the Bangladeshi market and consumers—lessons that may eventually help BASF explore new business opportunities.

Social businesses can also provide less tangible but equally important employee benefits. Giving employees an opportunity to become involved in a social business can give them a sense of purpose and new personal- and professional-development opportunities. By providing experiences that enrich the lives of their employees, companies can strengthen employee engagement, job satisfaction, and retention. These types of experiences are especially valued by today’s “Millennial” generation (those born between 1980 and 2000). For members of this generation, experiencing a sense of purpose is an integral part of their lives and plays an integral role in their career choices. (For more about the survey, see The Millennial Consumer: Debunking Stereotypes , BCG Focus, April 2012.)

Finally, achieving true social impact can also enhance a company’s reputation and brand by helping to build a network and goodwill with important stakeholders. Public campaigns to encourage corporate recognition of social issues demonstrate the growing power that external stakeholders can have on business success. Building long-term relationships across all of society—including public decision makers, opinion leaders, and influencers—through an integrated stakeholder-management approach is critical for building support for a company’s interests and operations.

Developing a Successful Social Business

“Social business is always about finding the right balance, the best solution between the contradicting requirements of social and business all the time.”

– Emmanuel Marchant, director of danone.communities Fund

Books and articles on how to start and manage a successful company are widely available—and likely found in the private libraries of most of the world’s top managers. Best practices for developing a successful social business, however, are not as well known. While social businesses can apply many of the same business principles to achieve financial sustainability, guidance on how to achieve and maximize social impact is less straightforward.

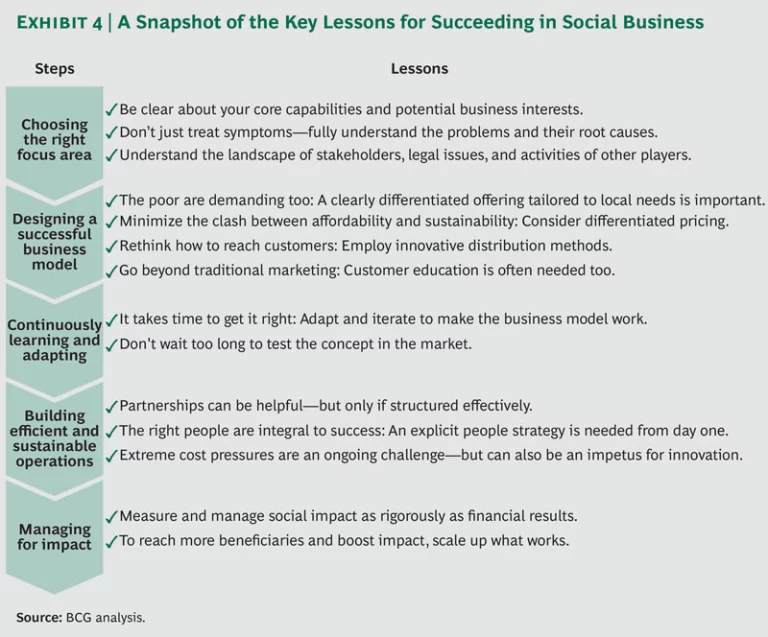

Drawing on the experiences of the Grameen companies and the insights of their managing directors in the field, we’ve identified a set of key success factors required for social business success. These factors are clustered across the five critical steps for developing a social business: choosing the right focus area, designing a successful business model, continuously learning and adapting, building efficient and sustainable operations, and managing for impact.

In the following sections, we look at these steps more closely, along with the key lessons associated with them. (For an overview of the steps, see Exhibit 4.)

Choosing the Right Focus Area

Any successful business identifies and meets a specific customer need. A social business is no different, except that it focuses its efforts on addressing an unmet social need or unsolved social problem.

Choosing which need to focus on requires considering three factors simultaneously:

- The core strengths, capabilities, and business agenda of the company that wants to engage in a social business

- The problems and needs that are the most pressing and underserved in a targeted geography

- The landscape of stakeholders, legal issues, and the activities of other players.

Be clear about your core capabilities and potential business interests.

When identifying a social problem to address, companies should start from a baseline of their core capabilities, goals, and learning agenda.

By targeting a specific need that their core capabilities can address, social businesses gain a clear sense of purpose and can generate real impact. Danone, for instance, drew on its own expertise in nutrition when it chose to address the problem of poor nutrition among children from the lowest-income families in Bangladesh. Similarly, Veolia Water built upon its capabilities in providing safe water solutions by addressing the issue of arsenic-contaminated drinking water in Bangladesh.

Understanding the goals and learning agenda of the organization also helps orient the company to particular problems while maximizing the potential business benefits. Intel, for example, lists as its central mission: to “create and extend computing technology to connect and enrich the lives of every person on earth.” While Intel’s commercial business already achieves this goal very successfully for many populations around the globe, Grameen Intel Social Business in Bangladesh provides an excellent opportunity for the company to learn more about how to reach even the rural poor and improve their lives with technological solutions.

Don’t just treat symptoms—fully understand the problems and their root causes.

When identifying a focus area, social businesses need to develop a sound understanding of the root cause or causes of the problems they’re considering addressing. While this might take significant time and effort, getting at the root cause is critical, since having a sustainable impact hinges on addressing a problem’s source—not just its symptoms.

Addressing the root causes was important for Grameen Veolia Water, a joint venture with Veolia Water, a leading provider of water treatment services. Given its core capabilities, Veolia Water identified the issue of providing safe drinking water to the people in rural Bangladesh as a potential focus area. In Bangladesh, from 37 million to 77 million people—a significant portion of the country’s 147 million inhabitants—are at risk of arsenic contamination.

As it turned out, there were several root causes. Despite growing awareness among villagers of the presence of arsenic-contaminated water, they continued to drink it. A 2010 UNICEF report noted that 80 percent of the local people knew arsenic could be a problem in tube-well water, and even though contaminated wells had been painted red to increase awareness, many villagers still used the wells either because there were no other alternatives or because of convenience and cost considerations.

Also, many people mistakenly believed that arsenic-contaminated water would have a dark color or fishy smell, when in fact it can’t be identified by sight or taste. Finally, because arsenic-related health problems appear only in the future, the villagers didn’t connect such problems to the water they had drunk in the past.

By understanding these underlying causes, Veolia Water realized that an effective solution would require addressing not only the availability of safe drinking water but also the local perception and use of water. While Veolia Water has undisputedly strong expertise in designing the right technical solution, the company realized that solving behavioral issues would require additional skills and a focus on educating the local people. (See the section “Go beyond traditional marketing: Customer education is often needed too.”)

Understand the landscape of stakeholders, legal issues, and activities of other players.

Understanding the landscape of players is important in any business activity. But it is even more important when aiming to address a social problem, as the social sector is often very complex and fragmented. Fully understanding the regulatory environment as well as the activities and plans of the many players that are active in a given social area is key to deciding whether a new engagement can truly deliver impact.

For instance, BASF originally planned to address the problem of malnutrition in Bangladesh with a multinutrient product. But its detailed review of the complex landscape directed it to another option.

Although malnutrition is a very severe problem in the country, as 43 percent of children under age 5 (that is, more than 8 million children) suffer from chronic malnutrition, the landscape of organizations working to address malnutrition is very complex and fragmented.

After investigating this complicated network of stakeholders in detail, BASF Grameen recognized that there were already plans for a similar product and that regulatory hurdles would be too high to allow for a quick market entry. Ultimately, BASF decided to focus on a different problem area, addressing insect-borne diseases through insecticide-treated bed nets—a field that aligned well with the companies’ core competencies.

Designing a Successful Business Model

An effective business model—with a clear value proposition—is as important to a social business as it is to a commercial business. The challenges that the social business model must tackle, however, are exceptionally difficult, particularly in the context of a developing country.

“Social businesses—as any other businesses—need a clearly differentiated product with a unique selling proposition.”

– Kazi Huque, CEO of Grameen Intel Social Business

BCG’s survey of managing directors at social businesses in Bangladesh revealed that chief among these challenges is gaining a deep understanding of the specific needs of the target population in order to design a clearly differentiated solution that meets those needs. Three other challenges were consistently mentioned: achieving a price point that the targeted population can actually afford, physically reaching those most in need, and generating sufficient demand for the new offering. An effective business model must explicitly address these four challenges.

The poor are demanding too: A clearly differentiated offering tailored to local needs is important.

Operating a social business that sells products to the poorest populations does not mean cutting corners on quality. Many financial demands compete for the limited budget held by the targeted population, which earns average daily incomes of only $1 or $2 per day. Poor customers, therefore, put exceptional emphasis on getting value for their money. This makes it critical to truly understand their needs and to address those needs with a tailored and clearly differentiated offering.

Solutions to social problems don’t always require developing entirely new goods or services. Existing products in other markets or business ideas from social entrepreneurs around the world may provide potential starting points. Danone and BASF, for example, leveraged existing products as starting points for their solutions in Bangladesh. When no appropriate product exists in the current business portfolio, it is well worth the effort to systematically assess the local and global landscape for existing solutions to similar problems and the lessons that can be drawn from their application.

To achieve real impact, however, a social business must tailor its product or service to the needs, culture, and local tastes of the targeted population. Standard solutions from developed markets rarely work. Market research in the field and consultation with local governments, NGOs, or partner organizations can help generate the insights needed from the local market to ensure a good fit between the solution and the specific local needs, as well as legal compliance, and a truly differentiated offering.

For instance, BASF tailored the insecticide-infused mosquito nets it sold in other markets to meet the needs of the Bangladeshi customer. Instead of sizing the nets to cover a single bed, the company adapted the nets to cover an entire sleeping family. Grameen Danone Foods innovated its yogurt formula by adding essential micronutrients needed to address local deficiencies. But to make the product appealing to local tastes, the company recognized that it needed to also thicken and sweeten its yogurt.

Minimize the clash between affordability and sustainability: Consider differentiated pricing.

One of the biggest challenges for social businesses is to sell products at affordable prices to the world’s neediest—often the poorest of the poor—while generating enough revenue to be financially self-sustaining. This can be a major hurdle for social businesses to overcome. Veolia Water, for example, had to convince people to pay for clean, uncontaminated water when river water, although less safe, was free. To overcome this hurdle, social businesses must achieve an affordable price point, while demonstrating the value of their offering.

Social businesses have three pricing options. One is to charge the lowest possible price to reach the people most in need. That’s an approach taken, for example, by Grameen Shakti. Using low-cost, manual production processes to build its solar panels, the company is able to achieve prices even lower than those of competing Chinese imports. However, there are limits to the extent social businesses can compete on price and still maintain adequate working conditions and minimum quality standards. Multinationals that let their standards slip run the risk of tarnishing their brands and reputations. For these reasons, competing on price against local companies that have fewer constraints is an ongoing struggle for social businesses.

When low-price leadership isn’t an option, social businesses can command higher prices only if their offerings are clearly differentiated. The poor—even more so than traditional consumers who are better off financially—thoroughly compare product value and price when making buying decisions. The second option, a moderate premium price, is possible if the additional value is very clear. For instance, BASF Grameen’s premium mosquito nets, which are infused with particularly effective repellent, sell for 30 percent more than standard nets—but are still sought after even by customers in rural areas.

Even when products are too expensive for low-income consumers, a “moderate premium” strategy can work if it is combined with financing options. For example, Grameen Caledonian College of Nursing charges young women €3,700 for their nursing training; to help make the tuition affordable, it can be repaid after graduation with a 5 percent service charge through the Grameen Bank. Grameen Shakti also offers a variety of financing options for purchases of its solar home system, with monthly installments equal to or lower than the monthly price of the kerosene alternative.

The third option is to price products differently for different customer segments, charging prices based on a customer’s ability to pay. For instance, Danone Grameen Foods charges less for its yogurt in rural areas than in the few modern trade stores in Dhaka, the capital of Bangladesh, where consumers can afford higher prices. Grameen Veolia Water sells its safe drinking water to rural customers via village tap points while more affluent customers in Dhaka are served with 20 liter jars sold at a higher price per liter. Grameen GC Eye Care Hospital charges more affluent patients full price for surgery and other treatments, which allows the company to treat the poorest customers at a far lower price. In each of these businesses, higher-income consumers subsidize the lower-income segments of the population.

Strategic, differentiated pricing such as this can make products more affordable to the target population while ensuring that overall operations at least break even and are thus sustainable. Given the very limited purchasing power of those most in need, it is often the only way to effectively reach the poorest of the poor.

A major challenge, however, is to properly identify different customer segments and ensure that the benefits of lower costs accrue only to the very poor. Some social businesses have found innovative ways to address this challenge. Grameen GC Eye Care Hospital, for example, has an outreach system that involves visiting potential patients in their villages, understanding their income levels, and verifying this information in separate meetings with the village elders.

Rethink how to reach customers: Employ innovative distribution methods.

The poorest people often lack access to basic products and services because they live in rural areas unreachable through established distribution networks. Poor, muddy roads and flooding can further complicate logistics, making transportation costly and time consuming. To succeed, social businesses often must rethink how they physically reach their target customers, supplementing traditional commercial channels with innovative methods of distribution.

For instance, Grameen Distribution originally relied on traditional channels such as the local distribution channels and local retail stores. But leaders at the company quickly realized that the more rural areas—at the end of the “last mile” of distribution—lacked access to essential products. By recruiting and training women within local communities—the so-called Grameen ladies who sell products door to door—Grameen was able to reach its target customers and provide valuable employment opportunities to women in rural Bangladesh. Today, Grameen Distribution employs roughly 9,000 women, men, and youth to sell products in Bangladeshi villages; they reach 9 million of the most remote households.

Go beyond traditional marketing: Customer education is often needed too.

For many reasons, getting target populations to buy and properly use a new social product is difficult. Products offered by social businesses may address needs that consumers aren’t aware that they have. A lack of education may keep people from understanding the value that the social business is offering. Finally, deeply entrenched behaviors and cultural or religious norms are often hard to change and require specific education to ensure proper usage of the product.

To create demand for its offering, a social business must develop marketing that effectively reaches and communicates a clear value proposition to the population in need. This is an area where the capabilities of the business and social sectors need to merge. While the business sector can provide the needed marketing expertise, this must be adapted to the social sector’s knowledge of the drivers behind customer behaviors in the targeted populations.

Many of the Grameen social businesses draw on the knowledge of local people to guide their marketing efforts. For example, the Grameen ladies are integral to the sale and marketing of many social businesses because they have firsthand knowledge of their neighbors’ needs. By explaining product benefits in a way that’s understandable to the target population and identifying opportunities for new products, the Grameen ladies offer a critical avenue for creating demand.

Even once demand is generated, customers often need to be educated on the proper usage of the offering. Several of the Grameen social businesses, such as Grameen Danone Foods and Grameen Veolia Water, offer products that require regular usage to be effective. Other offerings, such as the solar home systems of Grameen Shakti, require proper usage to maximize the effectiveness and working life of the product. To successfully change behavior, social businesses must go beyond traditional marketing and try new methods and channels such as educating consumers through door-to-door outreach and through advocacy by early adopters.

Grameen Danone Foods, for example, educates customers through small-scale events featuring a female student lecturing on the product’s nutritional benefits. Grameen Veolia Water uses local leaders to help overcome long-held beliefs and behaviors that are obstacles to behavior change. These efforts often require time, patience, and persistence.

Continuously Learning and Adapting

One thing we consistently hear from people who have been involved with social businesses is that getting the business model right is an iterative learning process that involves time and effort, trial and error.

It takes time to get it right: Adapt and iterate to make the business model work.

Be prepared for this step to take much longer than one might initially expect based on experiences with traditional business ventures. Throughout the development process, the business model must be continuously monitored and adapted to ensure that it is economically feasible and delivers real social impact. This learn-and-adapt cycle can be approached in one of two ways:

- Rapid Market Entry. This “learn by doing” approach involves entering a market quickly with a small-scale prototype and gathering direct feedback—an approach often used by entrepreneurs and startups that want to gain a first-mover advantage and try out new ideas in the marketplace quickly. Grameen Distribution went this route, adapting its model based on feedback from the Grameen ladies and their customers on products, pricing, and the door-to-door sales method. After achieving success on a small scale, the business was able to break even and rapidly expand its operations in less than two years.

- Thorough Advance Planning. By doing more thorough planning and testing in advance, a business can minimize its risk of failure and protect its investment and corporate brand. After up-front planning, pilot programs may be used to prove an offering’s potential for social impact and financial sustainability before scaling it up for entry in the broader market. This approach is more typical of corporations that set up a social business. Grameen Intel Social Business thoroughly developed its products and business model before starting pilot tests. Currently, shumātā—a software that monitors high-risk pregnancies—is being tested with about 1,300 women in three villages, and eAgro—an agriculture productivity tool—is helping about 900 farmers increase their crop yields.

Don’t wait too long to test the concept in the market.

While both rapid market entry and thorough advance planning can work, the best path forward for most multinationals may be a hybrid of the two approaches. Some up-front planning, market research, and refinement of the business model can minimize the risk of failure. But waiting too long poses its own risk because unless a concept is tested in the market, there’s no way to know if it will actually succeed. Unexpected challenges invariably arise, and things often turn out very differently than what was expected.

“We learned that it doesn’t really help you to plan more and more and more—your plan is going to be wrong.”

– Jochen Ebert, managing director of Danone India

Still, early market entry may seem too risky to some corporations. For these, starting a social business under a different name can be another option to protect their brand while getting real market experience quickly.

Building Efficient and Sustainable Operations

Social businesses aim to translate initial investments into self-perpetuating impact well into the future, but such long-run benefits can only be achieved if efficient, sustainable operations are put in place. To remain viable over the long term and increase the social impact they deliver, social businesses must structure operations and partnerships effectively, hire and retain the right talent, and design operations to be as lean and efficient as possible. Although these objectives are the same as in any business, social businesses face particular challenges in addressing them effectively.

Partnerships can be helpful—but only if structured effectively.

Many corporations find that partnering with a local company or social sector organization can provide valuable access to knowledge of markets and customer needs; support for local production, distribution, and administration; and an understanding of the specific challenges in the social sector. Grameen’s joint venture partners often cite the clear benefits gained from Grameen’s deep knowledge of Bangladeshi market dynamics, both in rural areas as well as in the country as a whole.

“Social business creates a common platform for the public sector, the private sector, and NGOs to work together on the resolution of social problems...This demilitarized zone allows collaboration modes, creativity, and a cocreation of solutions which no other modality allows.”

– Emmanuel Faber, co-COO and vice chairman, Danone Group

Corporations that decide to partner with a local social-sector organization often enter new territory. Ways of working in the social sector often differ from those in the business world. While these new interactions can be challenging for both sides, they often turn out to be very fruitful. Grameen’s focus on simple solutions, for example, required that Intel work at a lower level of complexity than a technology business typically would. Grameen’s approach encouraged Intel to think of new ways to make it easier for Bangladesh’s rural population to understand and use products such as mrittikā, software for analyzing soil nutrition and recommending fertilizer.

Partnerships can also be a source of conflicts—especially when the visions or expectations for the business are not aligned. Decisions about whether to set up a partnership with a local organization and, if so, which partner to choose must be considered carefully. To increase the odds of a successful partnership, agreements should be detailed up front to clarify key elements of the relationship. Critical to success are aligning expectations, creating a common vision at the outset, setting boundaries around operational areas that the company prefers to avoid, and clearly defining roles and responsibilities. Corporate partners engaging in a social business must also remain alert to any potential conflicts of interest with their commercial operations.

To encourage a long-term, sustainable partnership and to maximize mutual benefits, strong links between the parties must be integrated into all levels of the new social business. This integration should go well beyond the corporate CSR function and encourage engagement within the business units and top leadership. At Intel, for example, the joint venture is managed out of the company’s World Ahead Program, which aims to make technology accessible for people around the world through business endeavors.

Similarly, responsibility for the social businesses of BASF and Veolia Water lies within the respective business units and is closely coordinated with the regional and local commercial business structures. The top-level decision makers of all partners typically are represented on the board of the social business to ensure that their interests are considered when making strategic decisions. Equally strong links should be established among executives to encourage crossover benefits in both directions. Activities such as regular management calls and staff-rotation programs can help encourage ongoing cooperation and engagement.

The right people are integral to success: An explicit people strategy is needed from day one.

As with all businesses, a high-performance workforce is critical, but social businesses face particular challenges in recruiting and retention. Social businesses need employees and managers who possess both social and business skills, and finding the right mix of capabilities isn’t easy—especially in areas where educated, experienced employees are in short supply. This issue of scarce resources requires social businesses to start building local capabilities immediately to prepare

for long-term, sustainable operations. Grameen Danone Foods, for instance, brought in a team from Danone India to provide critical management skills on a temporary basis while local skills were developed in parallel.

Although it might sound surprising, social businesses in developing countries can face high rates of staff attrition. Despite their worthy and ambitious goals, social businesses often compete with large, for-profit corporations that can offer better compensation packages. As a result, some employees see their work as a temporary commitment, and they move on to higher-paying jobs once they’ve gained a certain degree of training or experience. While this can be a challenge for the social business, it is also a source of additional social impact. The social business acts as a stepping stone, providing training to—and helping develop critical skills among—employees who can then move on and spread their talent in other settings.

Still, high attrition is often a reality that must be anticipated and managed because it can threaten the social impact and financial stability of a social business. For instance, Grameen Shakti’s field staff has an annual attrition rate of approximately 25 percent. Important measures for managing high turnover include planning for attrition through recruiting, training new hires efficiently, and using incentives and clear career paths to encourage longer tenure.

Extreme cost pressures are an ongoing challenge—but can also be an impetus for innovation.

The cost pressures that social businesses face are exceptionally severe, given the low incomes of their targeted populations and the need to be financially self-sufficient in the face of low profit margins. Moreover, multinationals that set up social businesses must deal with wholly new customer segments, many of which are not accessible through traditional marketing and distribution channels. Success requires low-cost operations and innovative solutions, with a goal of doing more with less.

By applying the typical efficiency levers of traditional companies along with a mindset of risk taking and innovation, social businesses can optimize resources and maximize impact. Operations at Grameen Danone Foods are a prime example.

The yogurt business in Bangladesh required far less output than the typical Danone plant and low-cost operations to achieve affordable prices for the rural poor. By designing a new factory from the bottom up, Grameen Danone Foods developed a small-scale factory that produces just 2,000 tons of yogurt and uses state-of-the-art technology, local sourcing, and local labor to keep costs low and provide added employment benefits to the local population. Other improvements designed to minimize costs include increasing the plant’s capacity utilization and improving product and packaging design.

Managing for Impact

The moment of truth for a social business is finding out whether success has been achieved—and can be sustained and increased. Success means two things: delivering real social impact and doing so self-sustainably, without the financial support of a corporate partner or outside donations. Both of these outcomes can and should be measured and managed. While most companies are used to managing financial returns, managing social impact is often a new undertaking.

Measure and manage social impact as rigorously as financial results.

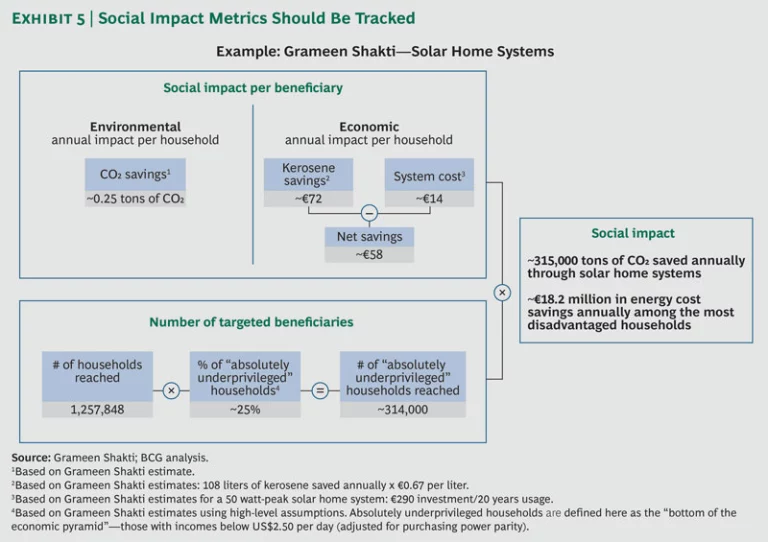

Although social-impact outcomes may seem intangible or difficult to evaluate, clear metrics can help quantify the impact of a social business on the target population. At a minimum, social impact should be measured along two dimensions: the impact on each beneficiary and the number of targeted beneficiaries reached.

To quantify the impact per beneficiary, key performance indicators must be tailored both to the social problem addressed by the business and to the social benefits expected. For example, a social business that provides green energy, such as Grameen Shakti, should measure the environmental and economical impact of its products. An initial analysis comparing Grameen Shakti’s solar home systems to the kerosene alternative, for instance, suggests that the average household with a home system reduces its carbon dioxide levels by roughly 0.25 tons per year and generates net annual savings of €58.

While the impact per beneficiary is important to understand, it is also critical to measure the scale of impact. Here, social businesses must distinguish between the total number of individuals or households reached (full scale of the business) and the total number of the targeted disadvantaged beneficiaries reached (degree of social impact).

A rough assessment of the impact of Grameen Shakti’s solar home systems, for example, reveals a total reach of about 1.2 million households, about 314,000 of which are estimated to be in the targeted poor segment. (See Exhibit 5.) It is important to closely monitor this metric, as Grameen Shakti’s ability to provide affordable green energy and cost savings to the most disadvantaged populations is a key element setting it apart from traditional commercial energy businesses.

These metrics, along with financial metrics, must be integrated into the management system of a social business. In this way, social businesses can learn to manage for social impact just as they do for financial returns: through end-to-end management processes that plan, measure, report, and improve performance. To reach more beneficiaries and boost impact, scale up what works.

Ultimately, increasing social impact requires scaling up the social business to maximize the number of beneficiaries reached.

“Big companies can reach people in many countries, deliver products to remote areas, learn in one place, and take knowledge to all other countries.”

– John E. Davies, general manager, Intel World Ahead Program

There are three routes to increase scale:

- Local scale-up aims to reach a broader customer base in a given country. For instance, Grameen Shakti plans to expand from more than 1 million solar home systems sold in 2012 to a cumulative installation base of more than 2 million units by 2015.

- Portfolio extension enhances the portfolio of a social business by adding new products or services. For instance, Grameen Distribution has expanded its portfolio with new social products, such as BASF Grameen mosquito nets.

- International expansion involves transferring a social business to another region or country. While none of the businesses highlighted in this report have yet taken this step, it is certainly an option for those that have reached significant national scale.

From a scale standpoint, Grameen Shakti has been the most advanced of the Grameen social businesses to date. The company was founded in 1996 to improve the supply of electricity in Bangladesh and to promote a healthier living environment in the country. When Grameen Shakti was formed, 70 percent of households in Bangladesh lacked electricity, and indoor air pollution was high because many families used kerosene stoves, which pose a fire risk as well. The company began by selling solar home systems to address the need for electricity.

Besides offering a range of affordable payment plans, Grameen Shaki’s “micro-utility” option allows the owners of the systems to sell power to their poorer neighbors, who might not otherwise be able to afford it. Through ongoing iteration and adaptation, the company has proved its ability to achieve social benefits and create a financially sustainable business.

Over time, Grameen Shakti has added new customers and expanded its product line to include biogas and improved cooking stoves—installing more than 700,000 stoves to date—in addition to solar home systems. Today, it is a thriving business with nearly €72 million in revenues and 12,000 workers.

Looking Forward

Although social businesses and similar hybrid models that combine social impact and business principles are still an emerging concept, they clearly have tremendous potential. In the future, it is conceivable that social businesses will become an increasingly strong sector in the global economy as their benefits and best practices become better known. We expect that social businesses will complement organizations in the public, private, and donation-based social sectors.

Several trends underpin the high potential for growth among social businesses and similar hybrid models. First, there is a growing interest among nonprofit organizations to increase the sustainability and efficiency of their operations—largely because donors and society are increasingly demanding it. Many nonprofits already have begun exploring new ways of migrating toward more sustainable business models and generating revenues through their operations. According to a recent survey, 40 percent of nonprofits in the U.S. and Canada with budgets of $250,000 or less—and 60 percent of those with budgets above $5 million—used a hybrid, socially oriented business model for a portion of their operations. Moreover, 87 percent of the organizations with a hybrid model expect to launch another one within the next three years.

Second, a wealth of new ideas and prototypes of social business models are available. Many social entrepreneurs are developing and proving new ideas that are ready to be financed and scaled up either independently or in partnership with nonprofits or corporations. A recent Global Entrepreneurship Monitor study estimates that roughly 2.8 percent of the working population in the U.S. is involved in hybrid social enterprises.

Feeding into this growth of new business models is the increasing academic attention that the topic is attracting. Journals on social business and social entrepreneurship are spreading, and many of the leading business schools—such as Harvard, Stanford, HEC Paris, and INSEAD—have established chairs or programs dedicated to the topic.

The regulatory environment and capital markets are also becoming more amenable to the development of social businesses. Governments are beginning to create legal structures designed to support companies with a social mission. For instance, the European Commission’s Social Business Initiative aims to provide a favorable environment for social businesses by improving access to funding and reducing regulatory and administrative requirements. Several development agencies, such as the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) and African Development Bank (AfDB), have also committed to promoting and developing social businesses.

Finally, more funding and support mechanisms—probably the most important drivers of growth—are emerging to encourage the incubation and growth of social businesses and other similar ventures. For instance, impact investment funds—defined as “investments intended to create positive impact beyond financial returns”—have become a significant funding source for social entrepreneurs and social businesses around the world. Organizations have also been created to develop the social investment market. For instance, U.K.’s Big Society Capital has budgeted £600 million to invest in social intermediaries, which can in turn provide support to social sector organizations. Innovative social-investment vehicles and structures are also beginning to emerge, such as stock markets specifically focused on social business.

As we have illustrated throughout the report, these developments present an important opportunity for the corporate sector. Companies increasingly seek to move away from traditional CSR, aiming to better leverage and integrate their socially motivated activities with the core business. Social businesses not only provide a more effective way to create social impact but also offer corporations the opportunity to harness a variety of business benefits, which themselves become increasingly important as a source of competitive advantage. Learning and innovation in new markets, particularly in developing economies, are key requirements for future growth. A clear sense of purpose and meaning is increasingly important for the current generation of young employees. Finally, in an ever more interconnected world, recognizing the importance of contributing to and engaging with all stakeholders of society will be essential for lasting business success.

The most natural and effective way for companies to approach social causes is with a business mindset. Large corporations are particularly well equipped for such endeavors; they possess the unique capabilities and resources required both to undertake small “experiments” and also to scale up existing approaches. Such engagements benefit their own business interests and the world as a whole.

Acknowledgments

Many thanks to all interview and discussion partners who significantly contributed to the creation of this report: K.M. Ashaduzzaman (Grameen Health Care Services), Ehsanul Bari (Grameen Krishi Foundation), Corinne Bazina (Grameen Danone Foods), Ahsan Ullah Bhuiyan (Grameen Shakti), Thérèse Blanchet (social anthropologist working for Grameen Veolia Water), Ajoy Chakraborty (Grameen Veolia Water), Melinda Daif (Danone), John E. Davies (Intel World Ahead Program), Fiamma Degl’Innocenti (Yunus Social Business Centre), Saori Dubourg (BASF), Tomoyasu Ebana (Grameen Yukiguni Maitake), Sophie Eisenmann (Yunus Social Business), Emmanuel Faber (Danone), Aam Mahbubul Haque Udoy (Grameen Health Care Services), Zahirul Haque (Grameen Distribution), Nazmul Haque (Grameen Distribution), Ashraful Hassan (Grameen Fabrics & Fashions), Isabelle Hellio (Veolia), Sajedul “Pavel” Hoq (Grameen Intel Social Business), Laëtitia Houdart (Grameen Veolia Water), Dr. Nazmul Huda (Grameen Caledonian College of Nursing), Kazi Huque (Grameen Intel Social Business), Shariful Islam (Yunus Centre), Tanbirul Islam (Yunus Centre), Luc Jonveaux (Grameen Danone Foods), Abser Kamal (Grameen Shakti), Amir Khasru (Yunus Centre), Eric Lesueur (Veolia Water), Asad Mahlende (Grameen Caledonian College of Nursing), Emmanuel Marchant (danone.ccommunities Fund), Lamiya Morshed (Yunus Centre), Shehla Nasreen (Grameen Shakti), Professor Barbara Parfitt (Grameen Caledonian College of Nursing), Fazley Rabbi (Grameen Shakti), Alexis Rawlinson (Yunus Social Business), Benoit Ringot (Grameen Veolia Water), Patrick Rousseau (Veolia Water), Saria Sadique (BASF), Satake Yukoh (Grameen Yukiguni Maitake), Aelia Schreder (Yunus Centre), Christian Schubert (BASF), Mustafa Shafkat (BASF), Aisha Siddika (Grameen Veolia Water), Imamus Sultan (Grameen Caledonian College of Nursing), and Labib Tarafdar (Yunus Centre), and Satake Yukoh (Grameen Yukiguni Maitake).

The report is coauthored by Professor Muhammad Yunus, Nobel Peace Prize Laureate 2006, founder of the Grameen Bank, and early developer and implementer of the social business concept; and Saskia Bruysten, cofounder and CEO of Yunus Social Business. Yunus Social Business is the international implementation arm focused on setting up and managing social business incubator funds around the world and collaborating with corporations to create social businesses.

We would also like to acknowledge Marissa Benson, Viviane Engels, Frank Meyer, Günter Rottenfußer, and Fabian Uhrich for their support in conducting the study on the ground in Bangladesh and for preparing this report.