The emergence of hypercompetitive Chinese companies over the past decade in industries from telecom equipment to solar panels has been a game-changing development in global business. Western incumbents that blithely dismissed Chinese upstarts as imitators capable only of selling low-end, low-tech products soon found themselves fighting for survival in their home fields. Now a new and bigger wave of Chinese challengers is about to hit the world scene and disrupt sectors as diverse as construction equipment, machine tools, auto parts, trucks, medical devices , and even nuclear power. Multinational companies need to change their perceptions of these Chinese challengers and start to address the potential threat.

One perception that must change is that the only advantage of Chinese products is that they are cheap. The real Chinese edge is a constant push for cost innovation. For Chinese companies, innovation is not always about achieving technological breakthroughs. It is about being competitive on price and delivering value for money.

Cost innovation can involve little more than improving the efficiency of a production line, removing nonessential features, or using alternative materials. The products of Chinese cost innovators may lack advanced technologies and a lot of bells and whistles. But the value-for-money approach of these companies gives them a huge edge in the fast-growing market for products that are good enough to meet their customers’ needs. Some Chinese cost innovators go on to disrupt entire markets with their low-cost business models.

There is no magic behind the emergence of the Chinese challengers. They start in geographic markets that are more price sensitive and in product segments that are relatively less technology intensive than those of Western incumbents. They then create the capabilities to go global. The final stage is to confront the incumbents in developed markets and more sophisticated product segments. The best time to counter the threat of the Chinese challengers is when they are still fostering these capabilities. Never wait until the direct competition begins.

Cost Leadership and Beyond

Multinational companies that assume they can rely solely on technological innovation to fend off these challengers are likely to be in for a shock. The rise of the middle market, particularly in emerging markets, has changed the rules of the game. Middle-market consumers are driving the need for “good enough” products that emphasize price competitiveness and sufficient functionalities, rather than customization and the most advanced technologies.

In the competition for the global middle market, the odds favor Chinese cost innovators—particularly those with the advantages of scale, research and technology capabilities, and global ambitions. The following are some common features of their strategy for success.

Scale Advantage. Large production capacity enables some Chinese companies to enhance their global price edge despite rising domestic wages. In China, local manufacturers of wind-turbine and coal-power generating equipment have about a 25 percent cost advantage over multinationals. More than 40 percent of this cost gap is due to the scale effect. Labor costs account for only one-third of the savings in wind turbines and one-quarter of the savings in coal power equipment.

China’s huge domestic market accounts for much of this scale advantage. Chinese companies supply almost 90 percent of the domestic wind-turbine market, which accounts for more than one-third of global demand. China’s three biggest suppliers of coal power equipment also dominate the country’s domestic market, which at one time accounted for two-thirds of global demand.

Innovation for Cost Competitiveness. Many Chinese challengers are continually finding unconventional ways to economize through product design, production processes, or choice of materials. As a result of its continual R&D efforts, for example, the Chinese battery maker BYD reduced its raw-material costs for nickel-cadmium batteries by replacing expensive nickel plate with a cheaper substitute. One Chinese renewable-energy company outsources noncritical parts to local suppliers, which it gathers into a single industrial zone in order to lower capital expenditure and processing costs.

Innovation to Provide Value for Money. Simply being cheap is no longer enough. Many winning products of Chinese cost innovators strike the right balance among price, quality, and functions. Zhongxing Medical’s line-scanning direct digital radiography (DDR) machines, for example, are adequate only for the most routine and simple functions, such as chest scans. They cost only one-tenth as much as Western multifunction flat-panel DDR machines. Yet Zhongxing quickly captured half the Chinese market, forcing Western competitors to cut their prices or even withdraw from China.

Global Ambition. The huge Chinese market no longer satisfies the appetites of domestic corporate giants, which aim to be truly global leaders. For example, Beiqi Foton, a leading Chinese truck maker, introduced its ambitious “5+3+1” international growth strategy in 2011. The plan calls for the company to build its own value chains in the five major emerging markets of Russia, Brazil, India, Mexico, and Indonesia and to break into the three major developed markets of North America, Europe, and Northeast Asia—in addition to maintaining its leadership position in China. Guangdong Nuclear Power, which accounts for more than half of China’s installed nuclear capacity, also announced globalization as its strategic direction in 2011. The company has already expanded into such emerging markets as South Africa, Belarus, Ukraine, and Thailand. Guangdong Nuclear even bid jointly with the French giant Areva on the United Kingdom’s Horizon project, a plan to build 6 gigawatts of nuclear-power generation capacity in the U.K.

Fostering Capabilities to Challenge Incumbents. Chinese challengers are aggressively creating the product offerings and R&D, manufacturing, distribution, and branding capabilities needed to compete directly with multinationals around the world. Such Chinese construction companies as Sany, Zoomlion, and XCMG have been acquiring European competitors to gain technology and market access. Medical-device company Mindray is building a direct-sales team in the U.S. to target large hospitals with more customized products. Other Chinese companies have acquired well-known brands and adopted dual-brand strategies to penetrate different price segments. The acquisition of Volvo by Chinese automaker Geely illustrates this strategy. Geely, which is known as a maker of economy cars, is keeping Volvo as an independent brand for high-end vehicles.

Time for Multinationals to Take Action

Even if the danger of direct Chinese competition in a multinational’s strategic markets appears to be remote, the time to begin taking action is now. Keep in mind that once Chinese cost innovators gain significant scale at home, they can disrupt a global industry with breathtaking speed. For example, Huawei’s share of global wireless-equipment shipments more than tripled from 2006 to 2011. The company now has its own proprietary fourth-generation (4G) wireless technology. Huawei even won a major 4G contract in Sweden, the home country of its largest rival. To become more competitive against the Chinese challengers, Western telecom incumbents have been forced to consolidate and restructure.

One lesson multinationals should learn from the telecom equipment sector is the need to address the Chinese threat before direct competition kicks in. This is particularly true in sectors in which Chinese challengers can quickly foster their capabilities with limited foreign pressure, thanks to such advantages as privileged access to the enormous domestic market, strong government support, rapid growth in good-enough segments, and huge product range.

The construction equipment sector is a good example. Its broad product range allowed Chinese manufacturers to first conquer price-sensitive and low-tech segments, such as cranes and concrete pumps. They then moved up to larger equipment, key components such as hydraulic parts, and relatively high-tech products like excavators. Chinese medical-device makers are benefiting from a huge expansion in the middle market triggered by the country’s health-care reform, which aims to standardize prices for treatments and upgrade basic health institutions at the local level. Such opportunities give Chinese cost innovators enormous room to grow in scale and capabilities.

In strategic, high-tech sectors such as nuclear power, where Chinese challengers face a catch-up challenge, government support has played an important role in fostering local giants. The Chinese government has helped such companies with policies that protect domestic manufacturers, for example, and that encourage multinationals to transfer technology.

Gauging the Chinese Threat

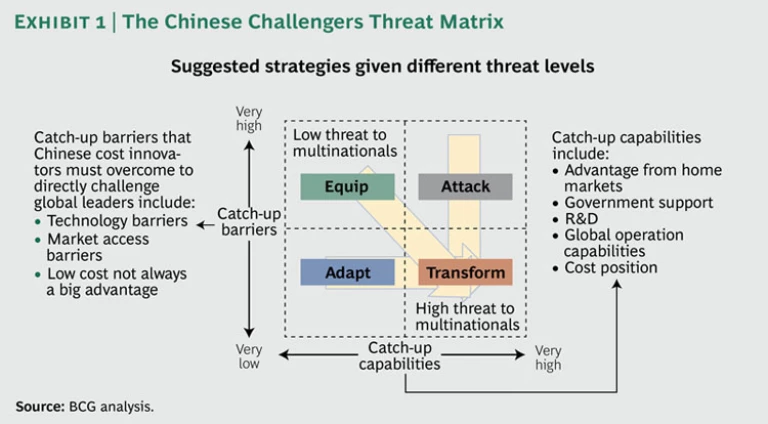

To mount an effective response, multinationals first need to understand the level of threat they now face from Chinese cost innovators. We have constructed a “threat matrix” that classifies the intensity of Chinese competition and suggests four basic corresponding responses: equip, adapt, attack, or transform. (See Exhibit 1.)

- Equip. In industries in which the catch-up barriers are high and the catch-up capabilities of Chinese cost innovators are low, multinationals should nevertheless act to preserve their dominant position for as long as possible. They should create sustainable competitive advantages and speed up globalization efforts.

- Adapt. In industries in which both catch-up barriers and the catch-up capabilities of Chinese cost innovators are low, multinationals should build strong cost advantages of their own and increase penetration in China and other emerging markets. That will give Chinese challengers less room to emerge in the home market and in the good-enough segment.

- Attack. In industries in which both catch-up barriers and the catch-up capabilities of Chinese cost innovators are high, multinationals should identify potential Chinese challengers and take preemptive action. This can include directly competing with the challengers, trying to acquire them, or joining forces in strategic alliances.

- Transform. In industries in which the catch-up barriers are low and the catch-up capabilities of Chinese cost innovators are high, it is often too late for defensive action or counterattack. Instead, multinationals in this situation are likely to require deep and comprehensive transformation.

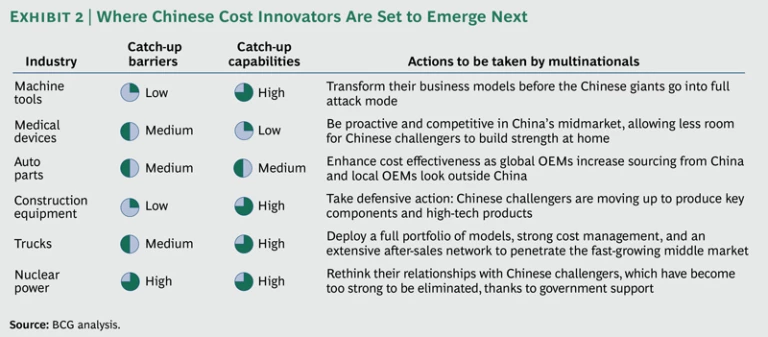

The industries in which Chinese cost innovators are next poised to emerge are at different points on the threat matrix. For example, because the ability of Chinese medical-device makers to catch up with multinationals remains low, incumbents need to limit the challengers’ room for growth by pushing to penetrate the Chinese market. In the nuclear-power sector, incumbents should rethink their relationships with Chinese challengers and figure out how to take preemptive action. The threat in the machine tool and construction equipment industries, however, is so advanced that incumbents should consider transforming their business models. (See Exhibit 2.)

Whatever strategic path they take, Western companies must understand that the Chinese challengers are not going away. They need to review their business models, product portfolios, cost positions, geographic footprints, and relationships with these companies. Multinationals should also get over their faith that technological leadership alone will always keep them ahead. They should adopt a broader understanding of innovation that focuses on finding better ways to serve and cultivate customer needs. Indeed, it may be time for multinationals to develop more of their own good-enough products aimed at the low-end and middle market. The best response to the threat of Chinese cost innovation could well be to become a leading cost innovator yourself.