3D printing, known more formally as additive manufacturing, is capturing growing interest from both industry and consumers. Opinions on the technology and its ultimate significance run the gamut. Some pundits consider it the spark that will launch the next industrial revolution; others deem it a fringe technology that is destined to remain the domain of geeks and hobbyists. What is the reality?

We believe that 3D printing will, in fact, prove a game changer for large swaths of industry—and, critically, that its impact will be felt far sooner than many people expect. The technology is already well developed and continues to advance; costs and prices are falling; investment in the industry, while still quite small relative to that in mobile technologies and wireless infrastructure services, is accelerating; and remaining hurdles to adoption are being surmounted. In short, 3D printing is on a fast track to mainstream adoption—and the time for companies to weigh the ramifications for their business is now.

The Potential to Reshape Industries

3D printing has been on the scene since the mid-1980s. It was conceived as a means of enabling prototyping, and prototyping remains its primary use. Its evolving strengths in this realm continue to win new users to the technology, particularly in manufacturing, where a robust 3D-printing capability in the design lab is quickly becoming table stakes.

But 3D printing has expanded beyond prototyping to the delivery of finished goods, where it stands to have an equally transformative impact. By providing a first-ever flexible, economical means of low-volume, customized or complex manufacture, 3D printing could radically change the business calculus of many companies. Indeed, it is already doing so. As we speak, companies (and consumers) are routinely “printing” items ranging from shoes to airplane parts—and doing so at a fraction of the cost associated with traditional manufacturing.

And these are early days. As the technology continues to develop, the rapidly shrinking list of things that 3D printers can’t produce will only shrink further. And critically, 3D printing also raises the specter of remote manufacturing. A product can be printed miles from the factory floor, be it at a local repair shop or in someone’s basement. Tesco is exploring the potential utility of having 3D printers in its stores; spare parts for previously purchased items could be printed on demand, for

What’s more, 3D printers are spawning products that only they could create. Many of these are truly remarkable. Consider two recent applications in the medical realm. Researchers at the U.S. Department of Energy’s Oak Ridge National Laboratory used a 3D printer to produce a prosthetic hand with miniature hydraulics that move the

The landscape that these changes usher in will present a range of opportunities—for innovative new products, cost savings, convenience, and business launches or expansion—to a wide range of businesses, including smaller companies. Indeed, says Eduard Neufeld, managing director of the Fogra Graphic Technology Research Association, the world’s leading research association for the printing industry, “3D printing stands to have its strongest strategic impact in cases where it helps to drastically lower risk and other entrance barriers for entrepreneurs who otherwise might not have the funds or the skills to push new ideas or start competing with established players.” But for many others, 3D printing will bring substantial risks.

Industrial-goods companies, for example, will see falling barriers to entry in many industries and will wrestle with the disruptive effects of remote-manufacturing capabilities on their business model. Consumer goods companies will see rising pressure on sales as consumers gain the ability to print products, legally or illegally, on their own. Transportation and logistics providers could face reduced demand for their time-critical, higher-margin services as fewer finished products, including spare parts, are shipped. While this may be offset initially by new volume from service providers such as Shapeways, which offers on-demand printing (and shipping) of digital designs, related demand for shippers’ more profitable long-distance services could fall as printing inevitably becomes more local. (The negative effects of these forces on shippers will be mitigated, to a degree, by increased demand for transport of the raw materials used in 3D printing.)

To be sure, 3D printing will not replace traditional manufacturing. Molding, casting, stamping, milling, and other time-tested techniques will remain vital, especially in high-volume production. “I wouldn’t expect this to steamroll traditional production methods,” says Neufeld. Rather, 3D printing will complement these methods—although it has the potential to substitute for them in a growing number of instances and applications. Panasonic, for example, which already uses 3D printing in the production of some OLED (organic light-emitting diode) panels for its high-end large-screen TV sets, now plans to use 3D printers to produce resin and metal parts to facilitate mass production of its consumer-electronics and household appliances. NASA is exploring the use of 3D printers in the production of parts for rocket engines that will power human space travel.

Approaching the Inflection Point

Companies at risk still have time to prepare. There remain hurdles that must be overcome before 3D printing reaches a critical threshold of adoption. For now, it remains limited to small production volumes, for example. Its production costs are still high compared with those of conventional mass production owing to its slow production speed and the high cost of raw materials. The number of raw materials that can be used in 3D printing is growing but still relatively small, and the range of properties they can deliver (for example, heat resistance) is relatively limited. (An owner of a small, custom heating- and air-conditioning-equipment business is watching this closely, however, as he ultimately expects 3D printing to be an economical alternative to injection molding. “I’m totally following this trend. Once the technology can handle 1-by-1-meter artifacts with heat-resistant materials, I’ll pounce on it.”) And combining different types of material in a single product remains difficult.

There are other challenges as well. Certain product designs, especially objects with bridges or overhangs, can be difficult for 3D printers to execute. The quality of 3D printing’s output can be lacking or inconsistent—cooling can cause shrinkage that compromises the accuracy of product dimensions, for example, and surfaces can be rough. The current price of 3D printers, both commercial and consumer grade, also poses a hurdle for many buyers, and there is a learning curve when it comes to using the devices.

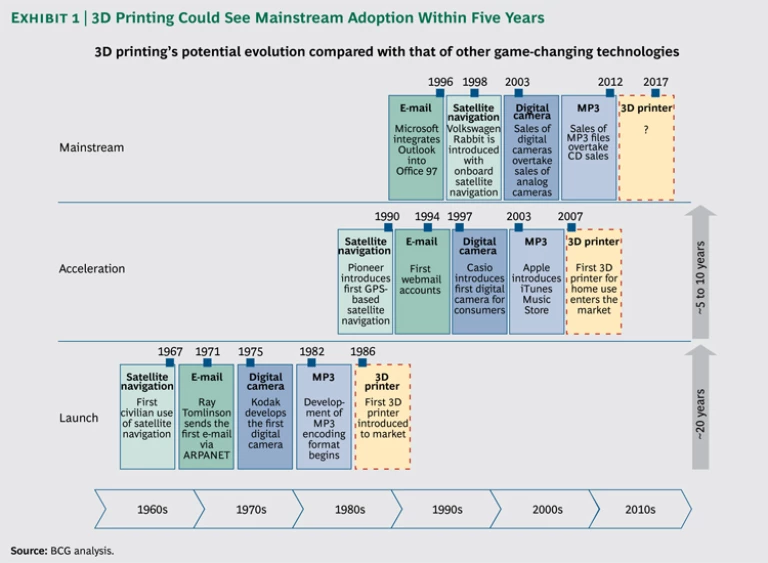

But these hurdles—like the minimum thickness of layers that can be produced, which has shrunk from 0.25 millimeter to 0.1 millimeter in the past five years—will continue to be overcome, and most should disappear within the next five years. This will pave the way for a surge in adoption and, potentially, mainstream status. (See Exhibit 1.)

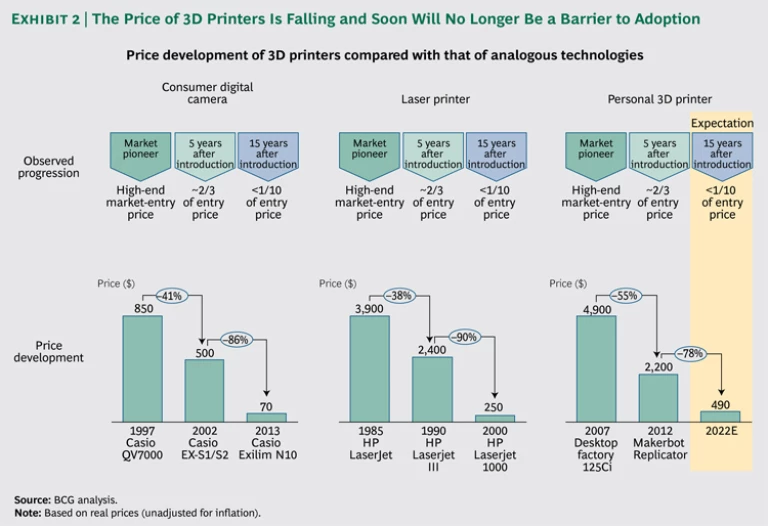

Consider some of the trends already in place. Following a trajectory similar to that of digital cameras, photo-finishing equipment, and conventional laser and inkjet printers, prices of 3D printers, for both industrial and consumer use, continue to fall. Soon price will no longer pose a hurdle for first-time buyers. (See Exhibit 2.) Some industry watchers believe that prices for entry-level machines, in fact, could fall below the psychologically crucial $100 level within the next two or three

Technological hurdles are also gradually being surmounted. 3D printers are producing output of increasing strength, for example; indeed, manufacturers of jet engines are starting to use 3D printers to produce parts. The size of printable objects is also increasing, as is the range of usable materials. The world’s largest 3D printer, developed by China’s Dalian University of Technology, uses industrial-grade

Simultaneously, the industry is broadening. Two competitors—Stratasys and 3D Systems—currently account for roughly three-fourths of the installed base of 3D printers. (Market leader Stratasys recently strengthened its position by acquiring MakerBot, a producer of 3D printer kits for the consumer and desktop market segments.) But many new competitors are emerging. Interest is particularly strong in the personal-printer segment, where global sales are growing quickly: 2013 sales are on track to reach roughly 42,000 units, compared with approximately 23,000 units in

In concert, outside elements that will underpin the technology’s adoption are emerging or already exist. Software that marries 3D scanning, modeling, and printing capabilities, for example—allowing for the easy copying and reproduction of existing objects, whether by consent or illegally—is becoming increasingly affordable. This stands to have major implications for 3D printing’s speed of adoption, just as it raises concerns and questions about product piracy and intellectual-property rights. There are also enabling communities that have formed in a spirit similar to that of the open-source community. An example is Thingiverse, a site that allows users to share digital designs that can serve as the basis for 3D-printed products.

In sum, 3D printing has a tailwind at its back. How quickly this leads to mainstream adoption remains to be seen—our current guess of five years or less might ultimately prove conservative.

A Digital Wonderland—for Companies That Are Prepared

The approach of ubiquitous 3D printing, coupled with the ongoing development of the technology itself, will force many companies to rethink their businesses and business models. Mold makers, for example, could see their model disrupted, or perhaps strengthened, by one of the many evolving subniches of 3D printing, namely printers capable of making very large molds from layers of paper laminated together—molds that can be used for large castings (such as engine

Companies will also have to rethink the individual capabilities necessary for success. Product development strategies, organization structures, legal capabilities and strategies, operational logistics and capabilities, and workforce and outsourcing strategies might all need to be adjusted if not overhauled.

The potential ramifications for companies’ IT could be particularly profound. IT departments will need to ensure that the necessary platforms, network capabilities, and storage and archiving structures and capabilities are in place, for example. The IT function will also need to support the development of whatever new strategic or tactical capabilities the company determines it needs to put in place, such as capabilities related to billing or intellectual-property management.

For companies, all of this is obviously a tall order. Where should you begin? Start—today—to think through the high-level implications for your industry. Engage in scenario planning. Monitor technological and regulatory trends. If you haven’t yet done so, experiment with the technology yourself. Try to determine whether and where your business is vulnerable and where there might be opportunity.

3D printing is likely to leave a profound mark on many industries, just as digitization has, and to do so sooner rather than later. Forewarned is forearmed.