Information technology outsourcing is a popular lever for companies seeking to drive down IT costs and improve agility and service quality. Yet, in many cases, it fails to deliver the sought-after

Many companies, however, forfeit considerable value—30 percent or more of the initial targeted value—as a result of problems related to contracting and contract

To ensure that they avoid the potential pitfalls, companies should institute a comprehensive optimization process for contracting and contract management—a process that spans the entire life cycle of the outsourcing contract. That life cycle can be divided into two phases: first, negotiation and contracting and then, contract execution up to the point of exit or renewal.

Negotiation and Contracting: Laying the Foundation for Maximum Value

The negotiation and contracting phase is focused on identifying the potential value available through outsourcing and then securing that value with a contract. It encompasses the tasks described below.

Defining an Outsourcing Model. This starts with a determination of what to outsource. Which of the company’s IT services can be better or more efficiently serviced by external providers? To make this determination, a company should define its outsourcing strategy and target operating model and divide its IT landscape into logical bundles. Each bundle will merit its own sourcing strategy. Once the scope of the outsourcing effort has been determined, the company must specify its targeted service levels.

Managing Negotiation Activities. This involves making sure that the interactions during negotiations are sequenced logically. It also entails ensuring that the right parties are involved in the discussion and that they play the right roles. The negotiation team should be structured to optimize the business value of the negotiation from the company’s perspective and to ensure that there is no loss of value during the transition to the vendor and beyond. Negotiation team members should thus come from both business and IT backgrounds. Furthermore, it’s important that the team include people who will run and manage the program on a daily basis. The company should also ensure that the vendor’s negotiation team mimics these dynamics and includes key contract managers, delivery representatives, and people who will be intimately involved in day-to-day value delivery.

The company ought to take steps to ensure that value is not lost during transitions between its various teams—technical, commercial, and legal—during negotiations. The risk can be reduced significantly by maintaining a stable core team throughout the process, having clear and complete documentation, and holding team member meetings focused on discussing the implications of handoffs and changes in personnel when they occur.

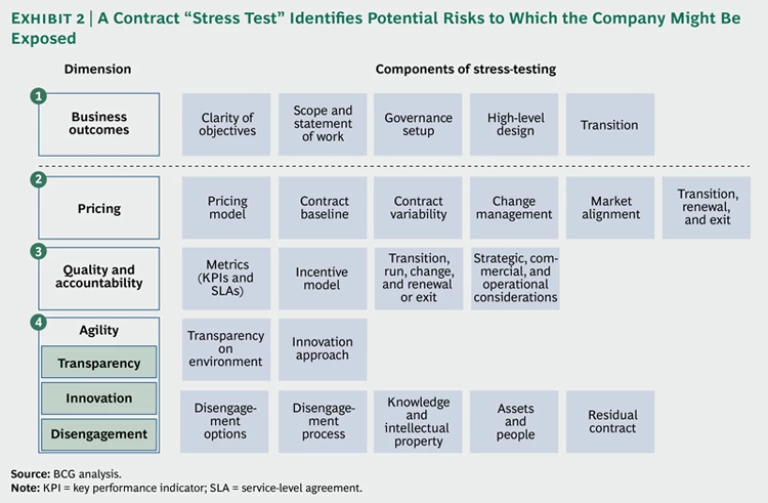

Ensuring That the Contract Accurately Reflects the Predefined Scope, Objectives, and Conditions. In addition to including the agreed-upon targets, the contract must also allow the company to capture the intended benefits and protect its interests under a range of conditions. A central element here is a risk assessment of the contract conducted through a “stress test”—a modeling of the evolving contract against multiple business scenarios, both relatively high- and low-probability ones.

A proper stress test comprises four steps: understanding the contract’s structure; defining scenarios, or changes in business conditions, that the company could face; modeling the contract under those scenarios to see how the company would be affected; and identifying the key risks—related to business outcomes, pricing, quality and accountability, and agility—to which the company might be exposed. (See Exhibit 2.)

Contract Execution: Realizing the Targeted Value

The goal of this phase is to ensure that the contracted value materializes. The company’s efforts ought to include three distinct thrusts: operationalizing the contract, managing the transition of activities to the vendor, and managing the contract on an ongoing basis.

Operationalizing the Contract. It is important to determine which operational levers will be necessary for ensuring that the agreed-upon value is captured on a day-to-day basis over the life of the contract. This effort includes the translation of contract terms into operational procedures. (Findings from the stress test should be used to help define these.)

Furthermore, it includes the creation of a “code of conduct” that will govern the company-vendor relationship and provide clear definitions of roles, responsibilities, and the consequences of underperformance. It should also describe the development and execution of a communication plan that identifies key stakeholders and their specific information requirements and establishes a process for regular communication.

Managing the Transition of Activities to the Vendor. This process will encompass a host of efforts, including, at the outset, the creation of a transition team, the definition of timelines and reporting tools, and the engagement of critical support functions, especially HR. It also entails addressing a wide range of nuts-and-bolts concerns such as the following:

- Establishment of connectivity infrastructure between the company and the vendor

- Resolution of potential issues associated with access rights and licensing

- Determination of how in-progress projects will be handled

- Management of the transfer of necessary personnel and knowledge

- Establishment of lines of communication with the vendor

- Ensuring that the necessary capabilities are present in the company’s retained IT organization

The final must-have for a successful transition to the vendor is the institution of governance. This demands not just the formulation of a plan but also a thorough, well-organized effort aimed at ensuring that the changes are understood and that they will stick. Absent this follow-through, problems could arise and linger, leading to a loss of value or greater-than-necessary efforts at resolution.

Managing the Contract on an Ongoing Basis. The company must ensure that the contract’s principles, terms, and conditions are understood, reviewed regularly, and adhered to by both the company and the vendor. The establishment of the code of conduct and governance procedures, including the use of incentives that steer the performance of both the vendor and the company, are key elements of this, as is timely communication.

Failure to skillfully manage the contract execution phase can result in a material loss of value. The experience of a financial-services company that had outsourced the coordination of key IT processes, such as incident and configuration management, is a case in point. The company had failed to secure adequate control of such key elements as governance during the transition stage and ongoing execution. This led to critical losses of clarity and accountability. For example, few of the people involved in the day-to-day execution of the 8,000-page contract thoroughly understood it or were familiar with its many specific clauses and agreements. This and related issues led to frequent and lengthy discussions about contract interpretation and adherence, ultimately prompting the company to take much of the outsourced work back in-house.

Companies that fail to pay sufficient heed to contracting in their IT-outsourcing initiatives often take a significant hit to their return on investment. The approach outlined above—which stresses thorough preparation and attention to detail both before and after contract signing—can do much to ensure that IT outsourcing delivers fully on its promise.

Stress-Testing the Contract: A Vital Step

Stress-testing can provide an effective means of revealing and mitigating the potential risks of a contract—before the deal is signed. Consider the example of an Australian government agency. Poised to outsource part of its information, communications, and technology services, the agency was concerned about the prospect of “value leakage” vis-à-vis its strategic objectives and performance targets.

To better recognize and limit its risk, during the negotiations, the agency modeled and stress-tested the proposed contract against a number of different business scenarios, including fluctuating government budgets, policy changes, and changes in demand for government services. The exercise proved invaluable: it helped the agency identify a number of key risks to which it was exposed and allowed it to take steps to mitigate those risks before the contract was finalized. These actions included negotiating a more flexible pricing model to better accommodate normal business changes and selected extraordinary scenarios; adjusting the vendor’s performance and accountability incentives to give the agency greater leverage for ensuring high-quality service at all levels (strategic, commercial, and operational) of the relationship; and dramatically reducing the agency’s risk exposure to larger changes or unforeseen events—by, for example, negotiating less stringent rules regarding asset levels and inflexible commitments to specific technologies.

A major consumer company found out the hard way that there is a serious downside to not stress-testing before committing to a major IT-outsourcing contract. The architects of the deal did not anticipate that the company would undergo a large-scale divestiture. And after the divestiture, the company was no longer in a position to meet the volume targets it had promised the service provider. Convincing the vendor to honor its original commitment under these new circumstances proved very difficult for the company.

Contract Execution: Realizing the Targeted Value

The goal of this phase is to ensure that the contracted value materializes. The company’s efforts ought to include three distinct thrusts: operationalizing the contract, managing the transition of activities to the vendor, and managing the contract on an ongoing basis.

Operationalizing the Contract. It is important to determine which operational levers will be necessary for ensuring that the agreed-upon value is captured on a day-to-day basis over the life of the contract. This effort includes the translation of contract terms into operational procedures. (Findings from the stress test should be used to help define these.)

Furthermore, it includes the creation of a “code of conduct” that will govern the company-vendor relationship and provide clear definitions of roles, responsibilities, and the consequences of underperformance. It should also describe the development and execution of a communication plan that identifies key stakeholders and their specific information requirements and establishes a process for regular communication.

Managing the Transition of Activities to the Vendor. This process will encompass a host of efforts, including, at the outset, the creation of a transition team, the definition of timelines and reporting tools, and the engagement of critical support functions, especially HR. It also entails addressing a wide range of nuts-and-bolts concerns such as the following:

- Establishment of connectivity infrastructure between the company and the vendor

- Resolution of potential issues associated with access rights and licensing

- Determination of how in-progress projects will be handled

- Management of the transfer of necessary personnel and knowledge

- Establishment of lines of communication with the vendor

- Ensuring that the necessary capabilities are present in the company’s retained IT organization

The final must-have for a successful transition to the vendor is the institution of governance. This demands not just the formulation of a plan but also a thorough, well-organized effort aimed at ensuring that the changes are understood and that they will stick. Absent this follow-through, problems could arise and linger, leading to a loss of value or greater-than-necessary efforts at resolution.

Managing the Contract on an Ongoing Basis. The company must ensure that the contract’s principles, terms, and conditions are understood, reviewed regularly, and adhered to by both the company and the vendor. The establishment of the code of conduct and governance procedures, including the use of incentives that steer the performance of both the vendor and the company, are key elements of this, as is timely communication.

Failure to skillfully manage the contract execution phase can result in a material loss of value. The experience of a financial-services company that had outsourced the coordination of key IT processes, such as incident and configuration management, is a case in point. The company had failed to secure adequate control of such key elements as governance during the transition stage and ongoing execution. This led to critical losses of clarity and accountability. For example, few of the people involved in the day-to-day execution of the 8,000-page contract thoroughly understood it or were familiar with its many specific clauses and agreements. This and related issues led to frequent and lengthy discussions about contract interpretation and adherence, ultimately prompting the company to take much of the outsourced work back in-house.

Companies that fail to pay sufficient heed to contracting in their IT-outsourcing initiatives often take a significant hit to their return on investment. The approach outlined above—which stresses thorough preparation and attention to detail both before and after contract signing—can do much to ensure that IT outsourcing delivers fully on its promise.