Two schools of thought dominate the realm of intellectual property (IP). Let’s call them the confrontational and the collective schools.

The confrontational view is built around asserting and defending legal rights, extracting royalties, winning judgments, and ensuring the freedom to operate. The most extreme practitioners are so-called patent trolls that demand royalties even though they themselves do not make goods or supply services.

The collective view starts with the premise that most innovation is incremental and that strong IP rights impede progress by putting up landmines and tollbooths in the way of subsequent inventors. “Copyleft” licenses allow free use of copyrighted works so long as modifications to those works are also free. This school of thought originated with hackers and academics and found expression in the development of open-software platforms such as Linux and its commercial offspring, Android and Chrome OS.

The business world, however, is not quite so binary. Business leaders should not let the lawyers and the hackers blind them to a broader range of strategies. The extremes of “sue” and “share” are not the only options.

Tesla Motors seems to be artfully avoiding this false choice. In June, the electric-car maker generated tremendous buzz when it announced it would grant competitors access to its patented technology. At first blush, this might look like a wholesale IP giveaway, placing Tesla clearly in the collective and copyleft school. But a closer look shows subtleties in the company’s approach.

The Five Dimensions of IP Strategic Intent

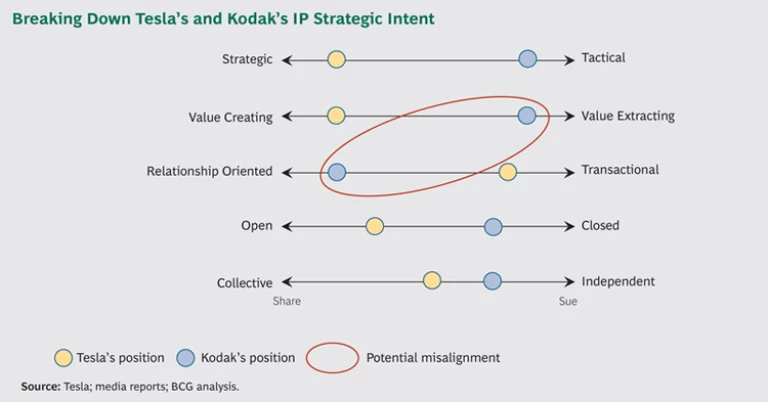

At BCG, we use five dimensions—referred to collectively as the IP strategic-intent framework—to think though the most effective way to use IP to win in the market. Each dimension runs along a continuum between the extremes of sue and share, and all five need to be both consistent with one another and in alignment with the company’s overall business strategy. The five dimensions can also help tease out the strategic intent of rivals’ IP moves. Using this framework to examine Tesla’s decision is revealing.

Strategic Versus Tactical. Does Tesla’s move support the company’s long-term business strategy, or is it more isolated and opportunistic, as when a company sells a nonessential part of its IP portfolio?

Verdict: Clearly strategic. Tesla could have used its strong patent portfolio to discourage rivals. Instead, by removing the threat that it will assert its patents, Tesla is trying to shape and accelerate the growth of the industry. The nascent electric-car industry is subject to network effects. The more charging stations and related infrastructure are in place, the more electric cars will be sold—driving manufacturing costs down. Lower costs will increase sales and encourage infrastructure investment: a virtuous cycle.

Tesla understands that it can’t build the industry single-handedly. As the company’s CEO, Elon Musk, wrote on his blog, “Our true competition is not the small trickle of non-Tesla electric cars being produced, but rather the enormous flood of gasoline cars pouring out of the world’s factories every day.”

The company has announced its intention to build a $5 billion battery factory—whose output could exceed Tesla’s needs—in partnership with Panasonic. Making its technologies available could encourage other automakers to buy Tesla batteries, as Toyota and BMW are already doing, helping the company move down the experience curve.

Value Creating Versus Value Extracting. Is Tesla merely trying to extract value from an established market through aggressive licensing, or is it trying to create new sources of value?

Verdict: Clearly value creating. Electric cars today have a 1 percent market share. By making its patents available to competitors, Tesla is trying to expand the size of the pie over the long term rather than insisting on taking the largest helping today, as patent trolls try to do. As the technological leader, Tesla will presumably profit handsomely through market expansion.

Relationship Oriented Versus Transactional. Is the initiative meant to be enduring and mutually beneficial, like the Nike–Apple partnership to commercialize Nike + iPod workout-tracking products, or is it a one-time opportunity?

Verdict: Somewhere in the middle. Press reports indicate that Tesla is working with Nissan and BMW to develop standards for charging stations and plugs in order to avoid a Betamax–VHS-type stalemate. Tesla wants to develop a “common, rapidly evolving technology platform,” in Musk’s words, but his statement did not refer to any relationships or partnerships with other companies or to making tool kits, annotated designs, or instructions available. The company does not want to be in the litigation business, but it is less clear how closely it wants to collaborate with others.

Open Versus Closed. Is the company making its IP assets widely available, or is it trying to gain advantage by keeping its technology proprietary? (The trade secret protecting the recipe for Twinkies and the formula for WD-40 is closed; standards are open.)

Verdict: Open, but with an asterisk. Tesla has not publicly offered zero-royalty licenses, which would be legally binding. It has simply pledged not to sue other companies if they act in “good faith,” a loophole-worthy phrase. Likewise, Tesla’s patents serve as collateral to secure financing, so lenders could eventually have a say in their use. Moreover, the carmaker retains valuable trademark and copyright protections.

Collective Versus Independent. Is Tesla’s goal to create common IP assets through collaboration or to go it alone and build and maintain an IP advantage?

Verdict: Hard to tell. In many ways, the move serves to blur the distinction. Tesla’s discussions with other companies on common standards and its will-not-sue pledge suggest a degree of collective self-interest, but the company has not made any broader promise to help its rivals. In contrast, a patent pool—such as the one created a decade ago to foster radio-frequency identification (RFID) technologies—falls clearly in the collective camp.

The Overall Verdict. Assessing Tesla’s move using the five dimensions of our IP strategic-intent framework reveals how working between the extremes of sue and share can significantly enhance an organization’s competitive advantage.

Could Tesla have gone further? If its strategic intent was solely to eliminate barriers and drive innovation, it could have done more, such as devising a copyleft-type license or abandoning its patents. But Tesla also has a business to run, so it took a more measured step.

Syncing IP and Business Strategy

The broader point is that companies in general need to be taking a more subtle and strategically aligned approach to their IP. Yet given the fragmented governance structure for IP in most organizations, with responsibilities spread across legal, R&D, operations, and individual divisions, consistency of IP strategic intent, let alone subtlety, is hard to achieve.

Inconsistencies in IP strategies can pose a significant risk. Consider Kodak. The company turned to aggressive licensing to stem losses and help finance its digital transformation away from film. While that value-extraction strategy provided short-term relief—between 2003 and 2010, Kodak generated more than $3 billion in IP revenue—it may have undermined its long-term strategy, which depended on forging partnerships with the very companies it was accusing of patent infringement. In the language of our strategic-intent framework, Kodak’s desire to create long-term relationships was out of sync with its short-term value-extracting activities. (See the exhibit.) Then-CEO Antonio Perez acknowledged this contradiction in the Wall Street Journal in 2010. In 2012, Kodak sought bankruptcy protection (from which it has since emerged).

Given the growing strategic importance of IP, it’s essential that business leaders rethink their approach—seeking to avoid the perils of inconsistency and chart a subtler course to enhanced competitive advantage between the extremes of sue and share.

In our experience advising clients, the IP strategic-intent framework creates a common language that helps senior managers identify and explore a broader range of strategic options, assess and ensure the internal consistency of their IP strategy, and break down the barriers among siloed IP stakeholders. Senior executives do not need to be fluent in the arcane intricacies of patent law to think strategically about relationship-oriented versus transactional initiatives, closed versus open innovation, and the rest. The framework helps support the critical conversations needed to ensure that IP strategy is internally consistent and supports the company’s overall business strategy.