A Kinetic Industry Calls for Four Areas of Change

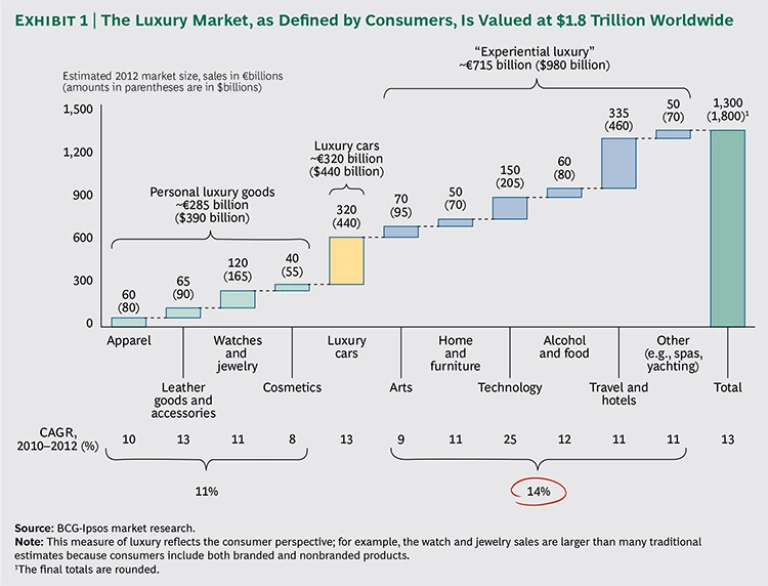

Consumers remain smitten by luxury. Their urge to splurge was revealed in a 2013 study by The Boston Consulting Group, which found that consumers spent an annual aggregate amount of more than $1.8 trillion worldwide on items the respondents defined as

That figure far outstrips the approximately $390 billion globally that is usually cited as total annual sales of luxury goods such as apparel, cosmetics, watches, and jewelry. Of the $1.8 trillion in annual luxury spending BCG has identified, sales of luxury cars account for more than $400 billion worldwide, and the business of luxury experiences—from private airline services to five-star restaurants—is already worth almost $1 trillion of the total.

In this context, the luxury market continues to buck the slow- and no-growth trends typical of many other industry sectors. BCG forecasts that after the past two years of 11 percent annual growth, the personal-luxury-goods sector will expand annually at around 7 percent over the next few years, outrunning the increases in GDP seen in most economies.

But what those raw statistics don’t show is how kinetic the luxury industry really is. We still see launches of lustrous new brands, bold acquisitions, equity stakes purchased by private-equity firms, and even start-up activity. Recently, LVMH Moët Hennessy Louis Vuitton spent $2.6 billion to buy cashmere clothier Loro Piana and then acquired Nicholas Kirkwood, J.W. Anderson, and

Many of the shifts in consumer behavior highlighted in our 2010 and 2012 reports on the global luxury market continue to propel the sector in more challenging directions—and in more complex ways. (For more about the trends see Luxe Redux: Raising the Bar for the Selling of Luxuries , BCG Focus, June 2012; and The New World of Luxury , BCG Focus, December 2010.) Emerging-market buyers are becoming prominent: together, Chinese, Brazilians, Russians, and Indians account for more than 30 percent of luxury consumption worldwide. Furthermore, experiential luxury continues to surge in emerging as well as mature markets; in China, for example, annual growth in luxury experiences tops 15 percent, highlighting both threats and opportunities for traditional luxury players accustomed to selling product there.

Brands must match such complicated changes with appropriate responses. BCG observes that success in luxury is linked increasingly to a brand’s mastery in four areas of change:

- New consumers, different segments, and buying behaviors that are not easy to decode

- A need to understand new geographies and the new specifics of cities as unique markets

- New and innovative business models, requiring openness and cultural changes

- Disruptions in marketing and selling enabled by new digital technologies

This report elaborates on those four dimensions of change, identifying where the leadership teams at luxury providers must place most of their energy and efforts in the future.

New Customers—and The New Ways They Buy

Recently, a wealthy Chinese individual spent $1.5 million on a luxury travel package that will take him to nearly 1,000 UNESCO World Heritage sites during a two-year trip. Meanwhile, his son, who had just bought his second Piaget watch,

These stories about the two men and two very deluxe experiences drive home two critical points about the changing face of luxury. First, the kind of luxury experiences, customized to their individual needs and interests, that both men are planning to enjoy are becoming increasingly common—and more and more of them are arising in the emerging world, from places such as Chengdu, Jakarta, and Santiago. Second, while the son still buys plenty of luxury goods, the father says he now favors experiences over new “things.” The different attitudes signal the importance of identifying and serving more detailed customer segments than has been typical of traditional market-scoping efforts. Both points deserve closer scrutiny.

The Shift Toward Luxury Experience

Worldwide, luxury is shifting rapidly from “having” to “being”—that is, consumers are moving from owning a luxury product to experiencing a luxury. BCG flagged this trend in its 2012 Focus report, Luxe Redux: Raising the Bar for the Selling of Luxuries . Experiential luxury, such as exotic holidays, gourmet meals, and art auctions, now accounts for 55 percent of global luxury spending. Sales of experiences also outpace product sales: BCG’s research has found annual growth in the category running at 14 percent compared with 11 percent for sales of personal luxury products such as watches, jewelry, and handbags.

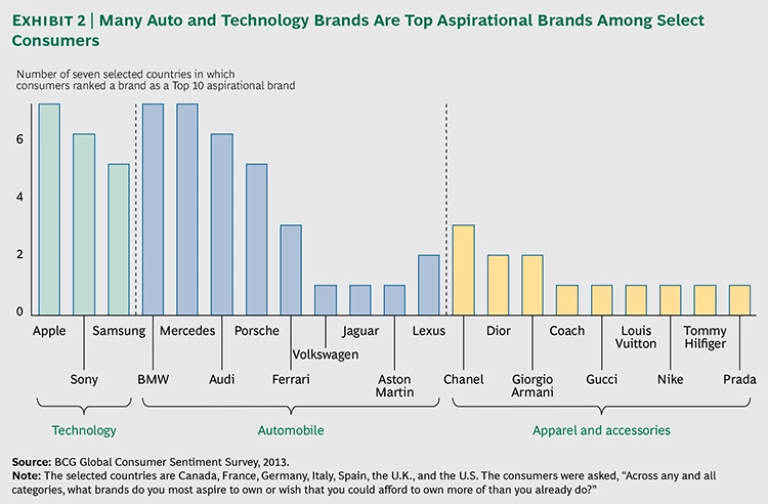

Within experiential luxury, growth levels of individual sectors have varied, with the technology sector achieving the highest compound annual growth rate: 25 percent. This is not altogether surprising given the nearly universal strength of technology brands today. In BCG’s 2013 Consumer Sentiment survey, affluent consumers praised Apple as the “most aspirational brand” in Canada, France, Germany, Italy, Spain, the U.K., and the U.S. Sony was in the top 10 in six of these seven countries; Samsung made the list in five of them. Yet Chanel, Dior, Gucci, and Louis Vuitton ranked in the top 10 in only a few of the countries. (See Exhibit 2.)

Consumers in emerging markets such as China and India are also rapidly shifting to high-end experiences, although spending on such experiences still represents a small portion of total luxury expenditures. BCG’s 2013 Global Consumer Sentiment Survey revealed that 29 percent of consumers in China prefer enriching experiences over products, versus 51 percent of consumers in the U.S. (For more about the Global Consumer Sentiment Survey, see The Resilient Consumer: Where to Find Growth amid the Gloom in Developed Economies , BCG Focus, October 2013.)

This reflects a natural purchasing trajectory: newly affluent buyers tend to amass tangible goods that show off their wealth. “The new Indian luxury consumer is pursuing a lifestyle where owning exclusive items and owning them first is a clear sign of wealth and power,”

In addition to this maturation in the consumption cycle, the move from “having” to “being” is driven by demographic factors. Baby boomers, now into retirement, are leading the way. As the first real purchasers of “democratic luxury,” these sixtysomethings and seventysomethings already own the watches and cars they want, so they seek enjoyable and often novel experiences on which they are prepared to spend handsomely. Falling in line behind them is the Millennial generation—those in their twenties who are geared to pleasure rather than possessions. To these young people, owning something usually comes second to sharing new ideas and

Luxury companies must embrace these key trends in the following three ways.

Enter the true luxury-experience categories. Luxury experiences are no longer limited to special occasions—the high-end restaurant, the deluxe spa, the yachting vacation, the private safari in Botswana. Now they are expanding to touch more of a consumer’s everyday activities.

Consider the branding and expansion of services ranging from superior dining to cosmetic surgery and exercise classes. Such services have several characteristics in common. First, they consistently enjoy demand that outstrips supply; waiting lists are long, and the lists themselves further spur the brands’ desirability. Second, the services’ pricing is far north of what is charged for functional versions of the same offering. Third, these “experience” brands regularly have a celebrity following. For example, Mick Jagger sometimes dines at New York City’s Café Boulud; actress Katie Holmes takes indoor cycling classes at SoulCycle. Fourth, makers of luxury products gladly tie their offerings to the experience brands. For instance, cosmetics brand Clarins collaborated on a summer offer with Barry’s Bootcamp, a high-end U.S. fitness studio.

SoulCycle is an excellent example of an “experience” brand that is reaching the everyday. Founded in 2006, SoulCycle offers high-energy indoor-cycling classes designed to help people enjoy working out; the instructors themselves have star billing. Priced at $30 to $40 a class,

Similarly, a number of high-end metropolitan hotels are expanding their offerings beyond mere hotel rooms to featured experiences. For instance, some organize exclusive events such as fashion shows, art gallery tours, or wine tastings that help their guests enjoy the city. Furthermore, some luxury automakers, noting that their exotic vehicles often sit in garages or are quickly resold after purchase, are striving to enhance the experience of owning their vehicles by offering selective memberships with perks to keep owners behind the wheel and talking about their cars.

Enrich the selling process. Turning sales activities into deluxe experiences in their own right is nothing new. But the practice is reaching new levels of excellence across a widening range of luxury segments—from automobiles to fashion—and across all channels. The intent is clear: to help consumers better connect with and experience a brand.

Customization is one “selling experience” technique. After customizing a desired model online, a Bentley buyer can track the manufacture and distribution of his or her car in real time. At least one maker of exotic cars invites its purchasers to its manufacturing facilities to participate in the experience of building the vehicle.

Burberry provides an even more sophisticated experience that spans several sales and marketing channels: its Runway Made to Order customization service. Just after its autumn show, the company offered a two-week window in which to order its Prorsum bags and outerwear online or in stores. Consumers could order items with a personalized engraved nameplate; during the nine-week turnaround period, they could view, on their smartphones, original sketches and videos of their item being constructed. They are slated to then receive their purchases before the collections arrive in stores.

Neiman Marcus has its NM Service, a personal shopping app that lets customers interact directly with “their” sales associates. Once a customer downloads the app, she receives access, via her smartphone, to a preferred personal shopper who can give advice live or set aside specific products for the customer to try on during her next store visit. When the customer enters the store, the NM Service launches, informing the preferred personal shopper, who can then greet and wait on the customer. The app also highlights upcoming store events, new product arrivals and sales, and

Elsewhere, Louis Vuitton has taken experience selling to another level—literally—with an invitation-only floor in its new super-luxury “maison” shop in Shanghai. Geared to China’s super-wealthy, the floor is decorated like a deluxe private residence. When shopping there, customers can have their hair styled

These examples just begin to explore the nearly endless range of possibilities. Brands can do much more to reinvent in-store service and to add experience to the selling process so the “theater of the brand” transcends the physical store.

Participate in new “experiential” business models. Recently, there has been a surge of innovative business models in which the experience of “sampling” luxury brands is the product. One such approach is the rental or subscription model. In the fashion and accessory category, the approach has been realized in new businesses such as Rent the Runway, Lacquerous, and Bag Borrow or Steal, whose “members” enjoy high-end fashion products for as little as 10 percent of the retail price.

Rent the Runway allows women to rent designer clothes and accessories. Rentals range from $50 to $200 for a four-night loan. Lacquerous presents itself as “a new club that allows you to try and wear the latest in red carpet and runway nail trends without splurging on a full bottle every time.” Bag Borrow or Steal offers a similar service in handbags, jewelry, and other accessories. Together, these three brands boast more than 3 million members and offer access to products from 170 designers.

Although some see such businesses as democratizing luxury—perhaps even diluting the participating brands—the new model clearly resonates with consumers, especially Millennials.

Similarly, customers can subscribe to receive boxes of fragrance and beauty samples. The emphasis is on the experience;

Birchbox

appeals to the thrill of discovery. Launched in 2010, Birchbox was one of the first startups to jump into the subscription-based business of selling fragrance and beauty products. For a $10 monthly fee, subscribers get a monthly package of four to five samples. Many customers have signed up to multiple so-called beauty box services; some

This model also lends itself to social media. Rent the Runway recently introduced a social-shopping platform, Our Runway , which allows women to shop based on user-generated photos of real women with body types similar to their own. And the model even translates into the physical world: Rent the Runway now has showrooms in Manhattan.

Some traditional luxury-goods brands and retailers have started to catch on to the power of these subscription models for marketing, driving conversion, and capturing data; a few are partnering with the startups to bring experiential consumerism to their shoppers. U.K.-based department store Harrods has teamed up with Glossybox to offer a curated box of sample sizes of cosmetics brands that Harrods already carries. One promotion gave subscribers a 20 percent discount at Harrods for the full-size versions of the products.

The Push for More Detailed Segmentation and Customization

If the 1990s was the decade when luxury brands began to reach broader segments of society, now is the time when luxury markets are fracturing again—although not along the usual fault lines.

Twenty years ago, luxury consumers were a more homogenous group. The single greatest factor that united them was their keen interest in accumulating logos as visible signs of status and wealth. Today, these same consumers come from all over the world; they are more educated about brands, more sophisticated in general, and much more demanding. They are likely to shop across multiple channels, and they routinely communicate online. Importantly, they are anything but homogenous—meaning that yesterday’s age-bracketed or geography-specific market labels matter far less.

Consider the “Chinese consumer” segment. In practice—as many leading luxury brands have discovered—grouping all the luxury consumers in China into one segment makes no sense. While some generalizations may still apply, there are dramatic differences in China that transcend the already huge economic variations across regions and across cities. (See Exhibit 3.)

One example of the new and better segmentation is the so-called Sugar Generation. The label describes China’s affluent young consumers who have grown up with abundance. They have been exposed early on to luxury brands and lifestyles, so their expectations and buying habits are “prewired.” BCG estimates that the Sugar Generation now accounts for 13 percent of China’s affluent population—and that it will grow to more than 30 percent within five years, as the “wealth history” of the average Chinese family becomes longer.

Both women and men in the Sugar Generation espouse very different buying habits than, say, China’s successful entrepreneurs do—most of the latter group are men and many of whom are the parents of Sugar Generation children. These young people know much more about luxury brands, and their purchasing behaviors are spread across a greater number of luxury categories, including experiential luxury. (For more information, see The Age of the Affluent: The Dynamics of China’s Next Consumption Engine , BCG Focus, November 2012.)

So what do such newly revealed market segments mean for luxury brands and retailers? Unlike mainstream consumer companies, many luxury firms have kept their distance from formal consumer research and analytics. Some might say their preference for “art” over “science” has indicated aloofness—perhaps even skepticism—for proven methods. Yet, for more than a few luxury firms, fierce brand protection and a defense of creative approaches seems justified by the considerable success that the firms have achieved.

Although BCG agrees that consumer research should never detract from the importance of creative, brand-enhancing product strategies, we contend that the formulas for success have become much more complicated. Luxury brands can now benefit significantly from consumer research that can yield fresh insights about market segmentation and go-to-market approaches. Such insights should inform decisions about store assortment, levels of in-store service, allocation of marketing spending, and pricing.

The research can also help companies respond to complex and fast-changing challenges such as understanding the life cycle of consumer values—that is, learning to distinguish the values that are becoming less prominent (ostentatious luxury), today’s dominant values (uniqueness, craftsmanship), and the emerging new values (sustainability, experiential luxury).

Because richer segmentation is needed to properly understand the new directions in which luxury markets are headed, BCG is working closely with Altagamma Foundation to derive unique customer insights based on deep research of more than 40,000 consumers in 20 countries. The first release of the report will be presented in the first quarter of 2014, and it will be updated annually.

New Geographies: Not the Country Markets You Thought You Knew

Most luxury players are planning for strong growth in what are still called “emerging markets.” Overall, this seems a valuable approach, given that the BRICMIT group of nations—Brazil, Russia, India, China, Mexico, Indonesia, and Turkey—will contribute around 55 percent of growth in global GDP between 2012 and 2017.

Recently, however, BCG has seen several leading brands starting to revisit their emerging-market strategies. While the reasons differ by country and company, we observe consistent themes that are tied to macroeconomic factors, shifting government policies, the advancing stages of urbanization and development, and changing tastes.

Consider China, for example. Consumer tastes there are changing very quickly, in part because the new Chinese government is cracking down on luxury gift-giving, in part because the one-child policy has spawned a generation of so-called little emperors, and partly given the rapid rise in consumers’ incomes. These changes are palpable, and many luxury companies have reported slowdowns in sales despite their years of investment in China.

BCG believes that luxury players must anticipate such changes by focusing not on country-level strategies—often their conventional market lens—but on city-level approaches or at least on strategies that target a cluster of cities whose inhabitants have roughly similar buying behaviors. We contend that brands must become much more specific in sizing and scoping markets; they need to plan their go-to-market strategies more systematically—including marketing, assortment, merchandising, and pricing—at the city or city-cluster level.

A comparison of Mumbai and New Delhi shows why. While both cities have large populations of high-net-worth individuals (HNWIs), Mumbai is the more multilingual and cosmopolitan of the two since it is home to residents from all over India. (Some liken the difference between the two cities to that between Washington, D.C., and New York City.) New Delhi, the capital, has many inhabitants from the north of the country, and migrant workers from Uttar Pradesh and Bihar to the southeast.

While both cities have their share of entrepreneurs and businessmen, Mumbai has proportionately more professionals—especially in financial services. Cultural, regional, and professional differences mean that New Delhi’s affluent prefer more flamboyant displays of wealth than their Mumbai counterparts.

Ahmadabad is another interesting Indian city; it is often called the “Manchester of India” thanks to its deep industrial roots. Its fast-growing per-capita incomes are twice the national average. So shouldn’t it be a prime target for brands? Not automatically: earning power and disposable income are only some of the many specifics to consider. The city’s affluent are largely Gujarati, an entrepreneurial community that puts investing ahead of spending, cherishes family values, loves travel, and prefers “lifestyle” purchases—that is, experiences—over luxury goods.

Of course, diversity among cities in the same country is not unique to emerging markets. Consider the differences between consumers in Minneapolis and Houston compared with those in New York, or between shoppers in Paris versus those in Lyon or Cannes. BCG’s finding is that cities are rapidly becoming more relevant than countries as target markets for luxury products and services.

Luxury buyers in Shanghai and Beijing have more in common with their counterparts in Paris and Tokyo than they do with those in Zhenjiang and Panjin. For this reason, brands must deeply understand the demographic and sociographic fundamentals in cities rather than, for instance, allowing consumer research conducted in a capital city to represent buying behaviors across an entire country.

A New Index of Luxury Buying

So where will growth come from? And which cities should be priorities for luxury brands? Where should luxury brands focus on optimizing their existing retail footprints rather than opening new stores? In which cities are tourists spending freely? Which categories of tourists are spending the most?

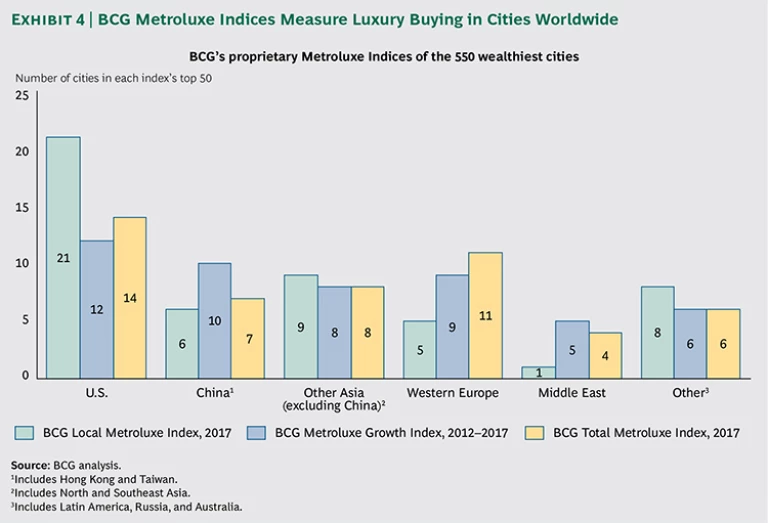

To begin to explore these questions, BCG has developed the Metroluxe family of indices (collectively called the BCG Metroluxe Indices) to measure the current luxury status and growth potential of the world’s 550 richest cities as defined by GDP per capita. Collectively, the cities in the index drive nearly 50 percent of global GDP. The individual indices are the BCG Local Metroluxe Index, the BCG Metroluxe Growth Index, and the BCG Total Metroluxe Index. (See Exhibit 4.)

Together, BCG’s family of indices balances both demand and supply factors.

- Local Demand. This measure takes into account HNWIs and the mass-affluent demographic. BCG defines HNWI households as those with more than $1 million in investable assets and defines mass-affluent households as having more than $100,000 in yearly household income, adjusted for local purchasing power parity and taxes. We also consider, at a country level, the propensity of local affluent consumers to spend on luxury.

- Tourist Demand. This measure calculates the impact of domestic and international tourism on luxury spending in the city.

- Supply-Side Drivers. This measure accounts for the infrastructure that supports luxury sales. It reflects, among other factors, the maturity of the distribution network (department stores, malls, and key shopping locations), logistics (such as the competence and quality of logistics services and customs clearance), and the sophistication of local fashion designers and the city’s design community.

Taken in its entirety, the collective index helps identify and prioritize future luxury growth by city, making it easier to explore each location’s distinct drivers of growth—for example, tourism versus local domestic spending.

Let’s look at the BCG Local Metroluxe Index first. This index projects the intrinsic potential of local luxury demand for each city in 2017, excluding tourist demand, supply, and other factors. While it does not capture where actual purchases will take place, it can help brands decide where to focus their marketing expenditures.

The BCG Local Metroluxe Index reveals that despite high GDP growth in key cities in emerging markets, U.S. cities account for 60 percent of the top 10 cities and more than 40 percent of the top 50 cities ranked by local luxury demand. Houston, Boston, and Philadelphia are in the top 15, indicating higher potential demand in these cities than in Shanghai, which is ranked 16th on the index, Beijing at 22nd, or even Seoul at 15th. Minneapolis, San Diego, and Detroit—ranked between 25th and 30th on this index—are better positioned than Kuala Lumpur at 36th, Mumbai at 43th, and São Paulo at 49th. This reflects the unsurprising reality that the U.S. is highly affluent, contributing about 20 percent of global GDP, 40 percent of the world’s millionaires, and 40 percent of ultra-high-income consumers (those with more than $30 million in assets).

North and Southeast Asia are prominent on the BCG Local Metroluxe Index; these regions have 9 cities ranked in the top 50. China (including Hong Kong and Taiwan) has six cities in the top 50. Interestingly, the whole of Western Europe is nearly as well-represented, with only London, Paris, Zurich, Berlin, and Munich among this index’s top 50.

The BCG Local Metroluxe Index gives a static view of local demand; however, another interesting index—the BCG Metroluxe Growth Index—provides a dynamic perspective, giving retailers’ viewpoints of projected absolute growth in dollars, by city, from 2012 through 2017. This index shows China and the U.S. relatively balanced as the two main contributors to the “top 50” ranking of cities. China (including Hong Kong and Taiwan) has 10 cities among the top 50. The nation boasts the highest absolute growth in luxury, measured in U.S. dollars—spurred, no doubt, by that country’s high GDP growth.

The U.S. has 12 cities among this index’s top 50—largely a reflection of relative U.S. affluence and strong trends in tourism. Given the upcoming relaxation of U.S. visa restrictions, tourism is likely to keep U.S. cities ranked high on the growth index. Western European cities are better positioned when tourism is factored in, with nine cities from the region in the top 50. The Middle East places well, with five cities on the list, two of which are in Turkey. (See “What Istanbul and Chicago Have In Common,” below.)

WHAT ISTANBUL AND CHICAGO HAVE IN COMMON

Luxury brands have often viewed market segments in terms of demographics and countries. But BCG’s analysis confirms that it makes more sense to think in terms of clusters of cities regardless of nationality—conurbations whose affluent buyers have more in common with each other than they do with others in their own nations.

Istanbul is a perfect case in point. With its population of nearly 14 million, the city accounts for most of the nation’s luxury market, which is valued at more than $10 billion and has been growing at about 15 percent annually. Like largely urban luxury markets elsewhere, Istanbul has seen its growth fueled not so much by the super-rich but by an expanding middle class, along with rising numbers of tourists from Europe and the Middle East.

A few statistics tell the story. Thirty percent of the hotel beds in Turkey are in five-star hotels, compared with only six percent in Spain. Upscale dining, where a meal costs $50 or more, is expanding rapidly, with the number of such restaurants in Istanbul growing by about 10 percent a year. With already 50 high-end restaurants per 1 million affluent people, Istanbul will soon be on a par with London, which has 100. (See the exhibit below.)

Much of the luxury purchasing in the city is of brands familiar to affluent consumers everywhere from Chicago to Tokyo: everything from Maserati cars to Gucci fashion accessories. In line with the global trend, experiential luxury is also luring Istanbul’s well-heeled—hence the rapid increase in high-end restaurants, for instance.

What about the world’s other supercharged cities? Moscow ranks 16th, and São Paulo is 12th. Mumbai and New Delhi have their share of affluent individuals, but neither makes the top 10. Although Indian cities’ demand for luxury goods will grow and the nation’s trade infrastructure will improve (currently, modern format stores account for only 38 percent of Indian spending on apparel, for instance), the changes will not be enough to move them high up the rankings, in part because many of India’s affluent do their luxury buying overseas. (See “Who Is the Mystery Shopper?” below.)

WHO IS THE MYSTERY SHOPPER?

Where is Mr. S. from?

He’s married, with two children. He works for an international bank and has a master’s degree in business administration from Columbia Business School in the U.S.

He wears Brioni, Canali, and Zegna suits, and he has a collection of watches that includes Breitling, Patek Philippe, and Hublot. He wears shoes by Ferragamo and Mauro Volponi.

Mr. S—he’s a real person—likes to shop in specialty boutiques; he frequently travels internationally and often shops while abroad. He is very discerning about what he buys: he prefers to buy handmade, highquality products rather than “buying a brand.”

Is Mr. S. from Chicago? London? Paris? Yokohama? No.

Rahul Sangupta (not his real name) was born in New Delhi and lives in Mumbai. He’s one of India’s elite—the nation’s highest earners. Sangupta has more in common with other affluent individuals in London and Singapore than he does with consumers in most cities in his native country.

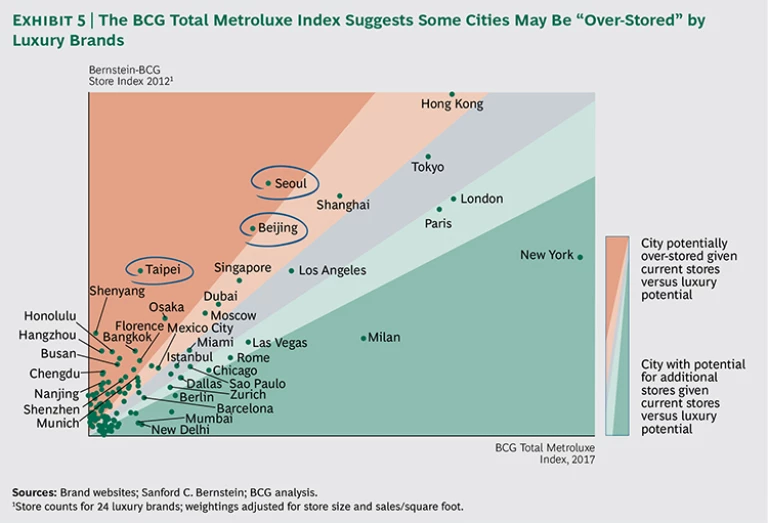

The third index—the BCG Total Metroluxe Index—is especially useful when its results are compared with those of a complementary measure, called the Bernstein-BCG Store Index, which provides a city-by-city view of the store coverage of particular city markets. (See Exhibit 5.) The Bernstein-BCG research shows that some cities in which brands have concentrated—for instance, Beijing, Seoul, and Taipei—have become “overpenetrated.” One conclusion: some brands may choose to scale back their retail footprints in some of those cities.

In other cities such as Dallas, Berlin, New Delhi, Mumbai, and São Paulo—where there is a larger gap between expected growth and the penetration of existing stores—we expect leading brands and retailers to open more retail outlets. There are also quite a few existing luxury “capitals”—New York and Milan among them—which seem surprisingly underpenetrated. Those cities are magnets for luxury spending by international tourists.

Insights to Help Brands Succeed as Demand Patterns Shift Worldwide

BCG envisions three ways in which these indices can help brands and retailers.

Conduct deeper market analyses at the city and cluster-of-city levels. Brands and retailers armed with a deeper understanding of local demand and consumer behaviors as well as more information about tourism and infrastructure at a city level can cluster cities beyond the geographic boundaries of countries.

To begin with, such companies will discover that go-to-market strategies will need to vary across cities in a given country. Consider Dongguan, for instance. This factory city is quite affluent; it is home to 2 percent of the Chinese individuals who have assets of more than $1.6 million. Yet the city also lacks major transport networks and a convenient airport. As a result, many of its wealthy shop internationally or in nearby Hong Kong. Although marketing in Dongguan still matters for luxury brands, a retail presence there is less critical.

Sydney and Melbourne are other interesting cities where expected long-term increases in wealth, coupled with burgeoning tourism from China and Japan, will buoy local demand for luxury brands for years to come.

From a marketing perspective, therefore, brands need to keep marketing locally and also market well in tourists’ countries of origin. From a retail perspective, assortments need to cater to demand from locals as well as tourists.

Localize go-to-market strategies. It is no longer enough for brands to target the elites in emerging markets with splashy ads for existing “Western” products and retail assortments. Now, astute brands are localizing their products and approaches. For example, Hermès has created its sari collection in India. L‘Oréal bought Yue Sai, a Chinese cosmetics brand, and in Brazil, LVMH bought Sack’s.

Montblanc is one company that is taking its localization initiatives to the city level. The pen maker successfully operates retail points in first- and second-tier cities in India, and it has regionalized its marketing materials accordingly. Store assortments also deserve to be localized.

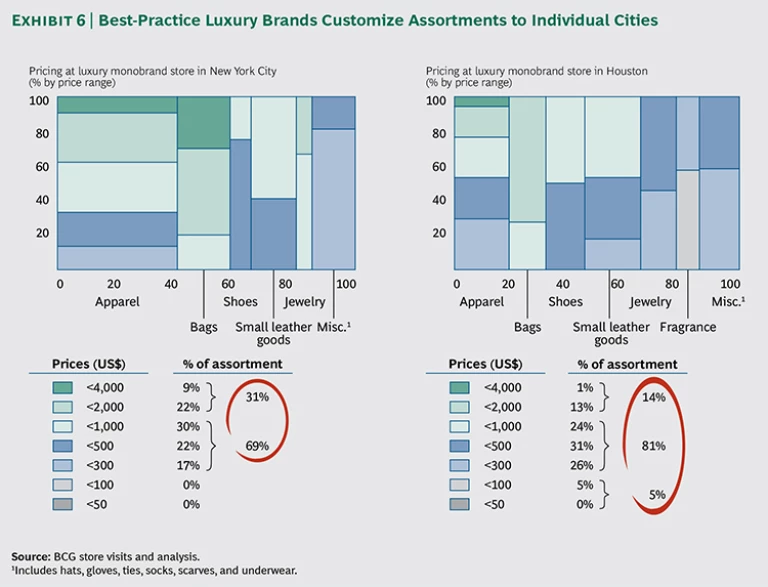

After surveying assortments offered in stores worldwide, BCG has found that best-practice luxury brands aggressively customize the retail assortment across cities. For example, a comparison of monobrand stores in New York and Houston revealed that 31 percent of the items sold in the New York stores cost more than $2,000 compared with just 14 percent of those sold in the Houston stores. (See Exhibit 6.)

Store format can also benefit from localization. These days, one-size-fits-all flagship stores in every city are far less effective than different formats applied to different tiers of cities. Gucci’s new approach to China is a good example. François-Henri Pinault, chairman and CEO of Gucci parent company Kering, explained it this way to Jing Daily: “Gucci is having to contend in China with a growing gap between consumer spending in major urban centers like Shanghai and Beijing and in secondary cities where luxury brands are

Gucci’s tiered approach to retail and merchandising means that in cities where the brand already has good business, the full product offering is available. By contrast, in new locations Gucci will offer “entry-level leather goods and accessories before gradually introducing ready-to-wear and other accessories as consumer tastes mature.” In addition to the new tiered model, the brand will pay more attention to optimizing within existing cities—moving stores as well as renovating and expanding existing locations.

With localized go-to-market strategies comes a need for simplicity of branding. Early efforts are under way: in 2012, Dolce & Gabbana folded its secondary D&G brand into the main label. Similarly, U.S. department store Barney’s has decided to rename all the Co-op stores as Barney’s, even though it may mean that smaller-format stores offer different assortments than those at the flagship stores.

Develop aggressive strategies for reaching tourists. The phenomenal proliferation of tourism will continue to drive growth for brands. Brazilians, Chinese, and Indians have been especially keen spenders while on vacation abroad. China is set to become the largest “source market” for outbound travel; tourists from that country are now the world’s biggest group of tax-free shoppers. By 2020, its overseas vacationers will constitute roughly 10 percent of the inbound tourists in the U.S., 30 percent of tourists visiting Japan, 30 percent of those in Sydney and Melbourne, and 20 percent of foreign travelers in Singapore. In South Korea, Chinese tourists already constitute 30 percent of the foreign visitor tally—a number that is expected to reach 50 percent just four years from now.

Chinese visitors typically spend 40 percent of their travel budgets on shopping once they reach their destinations, mostly on luxury goods and premium brands. Similar patterns play out in the Middle East. Istanbul is a strong beneficiary of this trend, drawing visitors from Syria, Iran, Iraq, and Azerbaijan, for example.

The key for luxury brands and retailers is to understand the tourist mix at a city level and to then develop strategies that create brand awareness before the tourists’ journeys begin, starting in their home countries. At the most fundamental level, brands must provide signage and other assistance in the tourists’ native languages at the holiday destinations. And they must invest in travel retail, given tourists’ propensity to buy luxury goods while in transit. (For more information, see Winning the Next Billion Asian Travelers—Starting with China , BCG Focus, December 2013.)

New Business Models: Why Alternative Approaches Now Matter So Much

There once was a time when luxury companies were essentially “brand islands”—havens of haute couture and high-priced exclusivity whose isolation from other business entities was essential to the luster of their brands.

Such a rarified approach is less tenable today. In a world of increasing openness—between customers and suppliers and between shoppers and brands, and with lines blurring between competition and cooperation—companies benefit by bringing in ideas and expertise from the outside. (For more information, see Luxury Ecosystems: Controlling Your Brand While Letting It Go , BCG Focus, June 2013.) In most other business sectors, senior executives have long accepted that their organizations’ future growth relies heavily on success with new technologies and in new market categories, cities, and channels—aspects they know they cannot master alone. So they have deliberately forged links to other entities and woven themselves into self-sustaining networks.

Luxury brands must do the same. Although many already have rich partnerships with other businesses, on the whole, they have been neither as focused on partnering nor as skilled at it as companies in other retail sectors. In short, luxury firms must do more to partner better. Three facets of partnering in particular deserve greater attention; we explore these below.

Reinforcing Partnerships and Sharing with Retailers

Historically, brand-retailer relationships have been less developed in the luxury sector than in mass-market categories. With products such as household supplies, food and beverage, and beauty, those relationships can be deep and broad, helping to accelerate top-line growth by increasing conversion rates, reducing out-of-stock incidents, improving promotion, and so on. Many makers of fast-moving consumer goods have “category captains”—managers or supervisors dedicated to driving those growth factors.

Luxury brands have not developed comparably strong ties for many reasons: their own need for tight control of their brands, the relative scarcity of customer data, and the fact that many retailers have been unwilling to share their customer data and have been keen to cultivate their own brand identities. But these days, big data and customer relationship management (CRM) tools mean that more customer data is accessible.

There are now realistic grounds to believe that brands and retailers can share a little to get a lot. For example, brands might seek from retailers greater visibility of store- or SKU-level sales data in exchange for exclusive rights to sell new products for a period of time before a broader market launch. Or they might offer retailers exclusive packaging or unique events to gain direct access to high-spending customers so that the brands can glean deeper insights through feedback surveys or product trials.

In short, brands and retailers today have greater opportunities to boost sales by bringing the right products to customers at the right times through the right channels. They can also gain by using tailored customer experiences to strengthen brand equity for both parties, and by joining forces to push omnichannel approaches to the next level.

Reframing the Value of Licensing and Joint Ventures

Although brands have a history of developing licenses, those arrangements have not always been of lasting benefit. There have been intrinsic conflicts of interest—the duration of typical contracts, for instance, and royalty structures that are generally driven by sales rather than profits. Consequently, some luxury houses have begun buying back licenses to gain more control over their brands. Thierry Andretta, CEO of Lanvin, put it this way: “Collaboration only if it’s right; licensing, no. We want to

But buying back licenses might not always be the right path. These days, enriching partnerships can be more effective than killing them. Joint ventures can be a prime way to appropriately align both parties’ interests. For instance, Kering, whose brands range from Brioni and Stella McCartney to Puma and Bottega Veneta, has joined forces with Yoox, the online luxury channel, to develop e-commerce for several of its brands.

Leveraging Vertical Ecosystems

In the last two decades, many luxury brands have moved to partner or acquire ownership of either upstream or downstream elements of their value chains—and sometimes both. The reasons are many—to assure suppliers, to reduce risks to quality, or to capture more manufacturing margin,

Chanel has taken a different approach with the creation, in 1997, of its Paraffection company. The company comprises independent ateliers d’art; almost all are firms such as the makers of fabric flowers, buttons, or embroidery. Chanel’s twist on verticalization is to let these workshops operate independently—even letting them supply its competitors. Lesage, for instance, supplies its

By contrast, Swatch Group has cut back on third-party deals to focus on its own brands. One key business segment—production—manufactures watches and chronological watch movements along with jewelry. Its electronic- systems unit develops and produces electronic components and systems related to watches. The company has also established direct distribution and retail channels, which include monobrand stores and a network of multibrand prestige-watch and jewelry boutiques.

There is no one approach to verticalization that works for all. But the strategy significantly affects the luxury business. It telegraphs to potential newcomers that the barriers to entry are exceptionally high. It also confers greater negotiating power for resources ranging from retaining rare “know-how” and

The Persistent Rise of Digital

For luxury brands as for every other type of business, the digital domain is here to stay. But it’s a domain where companies are still feeling their way. This leaves an enormous opportunity for the brands that are quickest to distinguish what works from what doesn’t.

Affluent consumers are leading the digital charge in luxury, as in other sectors. In the U.S., about 40 percent of affluent consumers (those earning more than $100,000 a year)

Until very recently, business leaders made definite distinctions between their digital channels and their “conventional” sales and communications paths. But those boundaries are quickly disappearing. One consumer might research handbags online and then purchase a bag offline. Another might buy a jacket online and then pick it up in a “bricks and mortar” store. And still another individual might try on shoes in a store but purchase them online in order to get a different color.

The proliferation of smartphones and tablets has accelerated this trend; “mobile” is everywhere, anytime—and at all stages of purchasing. Even before buyers enter a store, they are researching and accessing information. While in the store, they are checking product reviews, ordering out-of-stock items, and using mobile payment solutions. And after they leave the store, they are writing reviews and posting recommendations.

The interplay of offline and online channel behaviors varies by category. For example, furniture and decor sees more activity in the research-online-then-purchase-offline pattern, whereas shoes are susceptible to showrooming, in which consumers research a brand or product offline—often in a store—and then purchase online.

Slowly but surely, luxury brands have been responding to consumers’ digital enthusiasm. Online sales are too big to ignore: BCG estimates that e-commerce brings 17 percent of U.S. luxury sales today and that luxury e-commerce is growing twice as fast as the overall U.S. luxury market. Luxury e-commerce includes brands’ Web sites—which account for 20 percent of online luxury sales—and multibrand online sites, such as those of department stores, specialty stores, and single-category (such as shoes) online players. The multibrand sites account for 80 percent of total online sales of luxury products. Many are attracted to the economics of the digital world—particularly its relatively low investment costs. In general, brands are becoming more comfortable with how their reputations can be managed in the difficult-to-control environment of e-commerce.

The Importance of E-commerce and Omnichannel Mastery

For those with established e-commerce operations in developed online markets such as the U.S. or the U.K., Internet sales can account for 10 to 20 percent of total retail sales. Richemont reported eye-opening results for its online Cartier presence: in its first year, the online operation became Cartier’s fourth-largest revenue generator, behind the physical stores on Madison Avenue and in Beverly Hills and

To be successful in luxury e-commerce, brands must master the “3Cs”: commerce, content, and community. First, it is important to have a great site for commerce that allows consumers to see the product and that offers easy and intuitive navigation; on its site, for example, Saks Fifth Avenue displays every clothing product with a short catwalk video. Second, such sites must provide unique, rich content about brands; Net-a-Porter, for instance, has its own fashion magazine. Third, it is critical to build a strong consumer community; Sephora offers an example of this by encouraging consumers to share their purchases and recommendations with their friends and others via posts on Facebook and Pinterest.

But mastery of the 3Cs is not enough. Beyond developing attractive e-boutiques, brands must also focus on omnichannel strategies and integrate e-commerce and offline retail. As brands seek to maximize the lifetime value of consumers, they will want to focus on one of the key findings of BCG’s study: omnichannel consumers are more engaged and spend at least twice as much as offline-only or online-only consumers do.

Tory Burch appears to be on top of the omnichannel mandate. To entice consumers to use mobile channels, the brand’s mobile app provides exclusive products (SKUs that aren’t promoted through other channels), exclusive offers (automatic free shipping), and exclusive content (Tory City Guides). U.S. department stores are also leading the charge, offering delivery from, pickup at, and return to stores—often for free because the margins for luxury products can generally accommodate the extra cost.

One challenge to omnichannel success is the requisite rethinking of the organization model. It is difficult for a single department to encompass separate online and offline teams and still provide a seamless customer experience across channels. Fully merged teams aren’t the answer either; they can detract from the flexibility and agility of the online groups. Hybrid models are probably the optimal solution; each brand must find the right hybrid approach for its case.

Revisiting Channel Roles and Sorting Out New Channel Conflicts

Although some luxury brands might be able to focus largely on their own e-commerce channels, the fact is that in many categories, consumers experience brands—and buy them—across multiple channels. Therefore, brands must constantly consider the full spectrum of channels. There is no shortage of options: multibrand e-retailers such as saksfifthavenue.com and harrods.com; specialist e-retailers such as sephora.com and tourneau.com; pure online players such as Net-a-Porter and Zappos; flash-sale sites such as Gilt and vente-privee; and even marketplaces such as Amazon and eBay. Although these channels offer all kinds of opportunities, they also raise big issues, such as:

- More Intense Competition Across Channels. Many retailers provide customer propositions—such as cross-selling suggestions, videos of the products, better zoom functionality for the product images, enhanced size guides, and product reviews, for instance—that are better than those on the brands’ own sites.

- Total Price Transparency. While this isn’t an issue for all luxury brands, some find that price variations that were not obvious in the physical world are all too evident online. For firms that have many sub-brands and deep distribution across multiple sales channels, this is a huge hurdle; for those that discount as well, transparency becomes even more challenging.

- Risk of Overexposure. The wide-open accessibility of the Web contrasts sharply with the inherent limitations of exclusive physical stores.

Luxury brands must redefine what role each channel should play in terms of brand building, volume contribution, and profit generation. BCG’s proprietary analysis shows that the main drivers of economic value online are price (more expensive items generally cost more to ship), store turns (SKUs that turn fast incur lower inventory costs), and the weight and size of items (fragrances and beauty products cost relatively little to ship). For instance, shipping a high-priced jar of facial moisturizer or serum can yield very attractive margins.

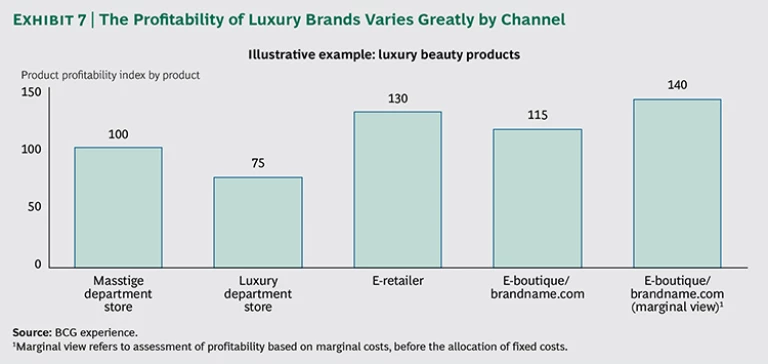

When all the requisite factors are considered, brands’ margins can vary greatly across channels, as seen in the example of one provider of beauty products. (See Exhibit 7.) Unsurprisingly, department stores are less profitable for brands, largely due to their high-service models. E-retailers can be more profitable than a brand’s own e-boutique, unless a marginal view is taken (that is, an assessment based on marginal costs, before the allocation of fixed costs) or unless an e-boutique reaches a certain scale.

With a deeper understanding of the economics and consumer purchasing behavior unique to each channel, luxury companies can redefine the roles, resources, and approaches (including target consumers, assortment and marketing, and cost to serve) appropriate to each channel. They can sharpen differentiations in product assortment, pricing policy, and marketing and communication. And they need to assume more of a test-and-learn approach rather than striving for the “perfect” channel strategy. None of this will be easy—omnichannel mastery doesn’t come overnight—but the payoff is substantial. It must be a key area of focus for luxury brands in the coming years.

Benefiting From the Rise of “Social” Marketing

Social media is the other digital domain that brands must master. As noted earlier, affluent consumers spend plenty of time on Facebook and other social sites. BCG has been tallying Facebook “fans” of leading brands for more than three years, and the figures show steep increases over that period, a surprising finding given that Facebook is now a relatively mature social network.

The luxury sector has more work to do to understand how best to use social marketing to increase customer engagement, develop new markets, and encourage and enable buyers to be brand advocates. It is not enough simply to collect “fans” and celebrate the number of “Likes.”

BCG finds that social media can be especially effective for reaching new customers in developing economies. In emerging markets, there is a “straight to social” trend: for example, India and Indonesia have Internet penetration of 10 percent and 25 percent, respectively, and 80 to 90 percent of those online are already using social media. (For more information, see The Internet Economy in the G-20: The $4.2 Trillion Growth Opportunity , BCG Report, March 2012.)

Increasing social engagement among customers. As noted, it’s one thing to amass a lot of fans but quite another to engage them deeply and then convert that engagement into sales. Engagement is more challenging in social media because brands and retailers have less control over their messages.

“Prosumerism” is one way to bolster engagement; consumers proactively participate in the design, manufacture, or development of a product or service. For example, Estée Lauder launched contests in which Facebook fans selected older products that they would put back into production. And Tiffany & Co. is working with prosumers to cocreate content—for instance, consumers upload their own photos to its site and tell personal love stories on Tiffany’s “The Art of Romance” and “What Makes Love True” pages. Overall, these brands are creating relevant, attractive, and authentic content with which to establish dialogues with consumers and boost engagement and ultimately sales.

Encouraging and enabling advocacy of brands. As the social marketing landscape evolves and microtargeting techniques improve, consumers are beginning to suffer from information overload. That’s why they are going back to “trusted sources”—that is, other users—to help filter information. In a recent BCG survey, 76 percent of consumers in the U.S., 74 percent in Brazil, and 78 percent in China said word of mouth is a trusted source of information for purchasing decisions. This compares with 37 to 53 percent (depending on the country) of consumers citing brands’ Web sites as a trusted source, 26 to 36 percent citing advertising, and 29 to 44 percent citing advice from in-store salespeople. (For more information, see The Resilient Consumer: Where to Find Growth amid the Gloom in Developed Economies , BCG Focus, October 2013.)

With that in mind, many companies have been striving to master advocacy marketing. There is nothing new about the idea of creating brand advocates—those enthusiasts who willingly and independently evangelize about a brand. But the rise of paid advocacy is worth watching.

Many brands are now paying the travel costs of influential bloggers and even “gifting” them. This approach should be practiced with caution because consumers may see it as inauthentic at best and unscrupulous at worst. BCG argues that there is more power in developing altruistic, reciprocal relationships with the most-critical influencers to turn them into authentic advocates. (For more information, see Harnessing the Power of Advocacy Marketing , BCG Focus, March 2011.) Advocacy initiatives, as stand-alone programs or coupled with CRM systems, can have a huge impact—in ways that are invisible to competitors.

The Top Agenda Items for Luxury Executives

So how should luxury executives start to steer their organizations toward the future? The following ten themes should be on the agenda at the next leadership meeting.

- Raise the level of consumer understanding. Luxury companies have not been particularly consumer-oriented. Today, their markets comprise many specific segments, each with different aspirations, behaviors, and attributes. It is crucial to understand the motivations and needs of each distinct segment—and then customize relationships and go-to-market strategies.

- Localize by city or cluster of cities. It is increasingly important to decide what to sell to whom and how. It is even more important to make these decisions city by city (or by clusters of cities) in order to cater to affluent local clients and international tourists. Cities rather than countries provide the most valuable lens through which to view consumers.

- Develop a clear tourist and travel strategy. Such a strategy must encompass three elements: a revised incentive and organization structure that promotes tourist-and-travel retail and cuts across a company’s internal silos; significant marketing in tourists’ home countries, with some support marketing in the holiday countries; and customized in-store experiences in the holiday destinations (for example, ads in the tourists’ languages).

- Invest in experiential luxury. No luxury firm can ignore the accelerating shift from “having” to “being.” There are now many ways to diversify a brand—through renting or sampling, for example. Brands can also deliver outstanding in-store experiences for each customer; retailtainment—using events such as art installations and fashion shows to make the in-store experience more theatrical and memorable—is a good way to do that.

- Do not overlook the myriad of opportunities in countries where luxury buying is long-established—even as you keep pushing into emerging countries. U.S. cities rank as 12 of the top 50 cities worldwide experiencing growth in luxury purchases—that’s two more cities than China (including Hong Kong and Taiwan) has on the list.

- Simplify brand architecture. Today’s consumers are unwilling to deal with the complications of multiple brand identities under a corporate brand. The same “brand name” can be stretched across price points and categories or used to target different consumer segments while maintaining a consistent image.

- Build new ecosystems of partnerships. Luxury firms must find ways to be in control of their brands while being more open with retailers and suppliers. For most firms, new growth will come from new categories, new geographies, new channels, and new technologies. Luxury firms are unlikely to master all these new fronts on their own.

- Apply the 3Cs to boost e-commerce. Find ways to excel in and Promote omnichannel marketing so that online and offline interactions become part of the same experience for consumers.

- Rethink channel priorities and strategies. Promote e-boutique and e-retailing approaches with clear objectives and differentiated roles and assortments.

- Build advocacy marketing. Generate positive “word of mouth” by leveraging close relationships with key influencers.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to offer their sincere thanks to Sonja Baderschneider (partner and managing director, Helsinki), Olavo Cunha (partner and managing director, São Paolo), Joel Muniz (partner and managing director, Mexico City), Abheek Singhi (partner and director, Mumbai), Miki Tsusaka (senior partner and managing director, Tokyo), Deran Taskiran (former partner and managing director, Istanbul), Jessica Smith (project leader), Paolo Meroni (project leader), Marjorie Condoris (consultant), Aditi Sawhney (consultant), Bobby McWatters (associate), Gillian Moore (senior analyst), and other BCG colleagues for contributing their insights and for helping to draft this article. Special thanks go to Mario Ortelli, senior research analyst in the luxury goods sector at the research firm Sanford C. Bernstein, for his thought partnership.