Introduction

The global wealth-management industry delivered a few surprises in 2013. Excellent growth did not always translate into higher profits. The mature economies of the “old world” and the rapidly developing economies (RDEs) of the “new world” continued to move at different speeds in general, but some developed economies performed extremely well, shifting the playing field. And sophisticated digital offerings are increasingly becoming a source of competitive advantage.

Global Wealth 2014

- Riding a Wave of Growth

- How Have Wealth Managers Fared?

- Wealth Managers Face a Digital Dilemma

Overall, the key challenge in the old world remains how to make the most of a large existing asset base amid volatile growth patterns, while the principal task in the new world is how to attract a sizable share of the new wealth that is being created more rapidly than ever. Players in every region will be required to forge creative strategies in order to deepen client relationships and lift both revenues and profits. But the road will not be easy. Indeed, most wealth managers continue to face common challenges in terms of gathering new assets, generating new revenues, managing costs, maximizing IT capabilities, complying with regulators, and finding winning investment solutions that foster client loyalty. The battle for assets and market share will become increasingly intense in the run-up to 2020.

In Riding a Wave of Growth: Global Wealth 2014, which is The Boston Consulting Group’s fourteenth annual report on the global wealth-management industry, we explore the current size of the market, the present state of offshore banking, and the How Have Wealth Managers Fared? BCG Benchmarks Their Performance in a wide range of categories. We also examine the growing Wealth Managers Face a Digital Dilemma , along with the most profitable business models—all with an eye toward the steps that wealth managers must take to position themselves advantageously.

Our goal, as always, is to present a clear and complete portrait of today’s wealth-management industry, as well as to offer thought-provoking analysis of issues that will affect all types of wealth managers as they pursue their growth and profitability ambitions in the years to come.

Market Sizing: A Robust Year

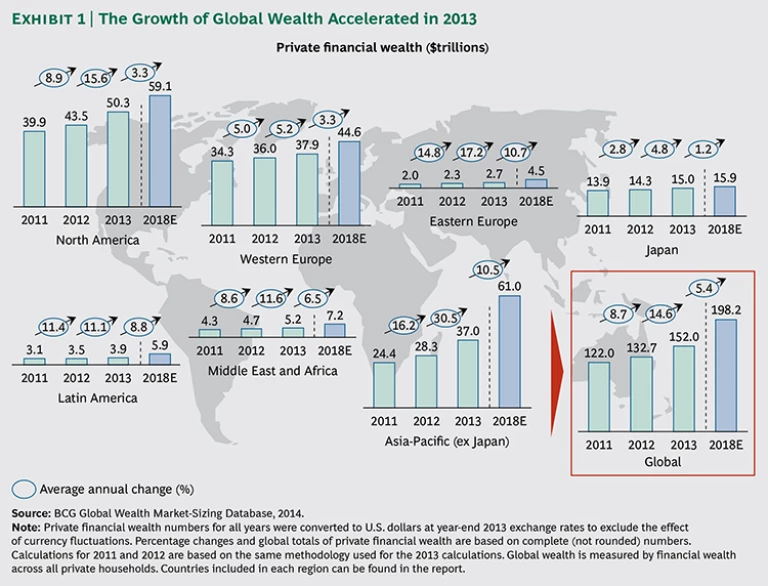

Global private financial wealth grew by 14.6 percent in 2013 to reach a total of $152.0 trillion.

The growth of private wealth accelerated across most regions in 2013, although it again varied widely by market. Global Wealth 2013: Maintaining Momentum in a Complex World , the Asia-Pacific region (excluding Japan) represented the fastest-growing region worldwide, continuing the trend of high growth in the “new world.” But substantial double-digit increases in private wealth were also witnessed in the traditional, mature economies of the “old world,” particularly in North America. Double-digit growth was also seen in Eastern Europe, the Middle East and Africa (MEA), and Latin America. Western Europe and Japan lagged behind with growth rates in the middle single digits.

As in previous years, North America (at $50.3 trillion) and Western Europe ($37.9 trillion) remained the wealthiest regions in the world, followed closely by Asia-Pacific (excluding Japan) at $37.0 trillion. Asia-Pacific, which in 2008 had 50 percent less private wealth than North America, has since closed that gap by half. Globally, the amount of wealth held privately rose by $19.3 trillion in 2013, nearly twice the increase of $10.7 trillion seen in 2012.

In nearly all countries, the growth of private wealth was driven by the strong rebound in equity markets that began in the second half of 2012. All major stock indexes rose in 2013, notably the S&P 500 (17.9 percent), the Nikkei 225 (56.7 percent), and the Euro Stoxx 50 (14.7 percent). This performance was spurred by relative economic stability in Europe and the U.S. and signs of recovery in some European countries, such as Ireland, Spain, and Portugal. A further factor, despite the tapering of quantitative easing in the U.S., was generally supportive monetary policy by central banks. In an exception, the MSCI Emerging Markets Index fell by 5 percent.

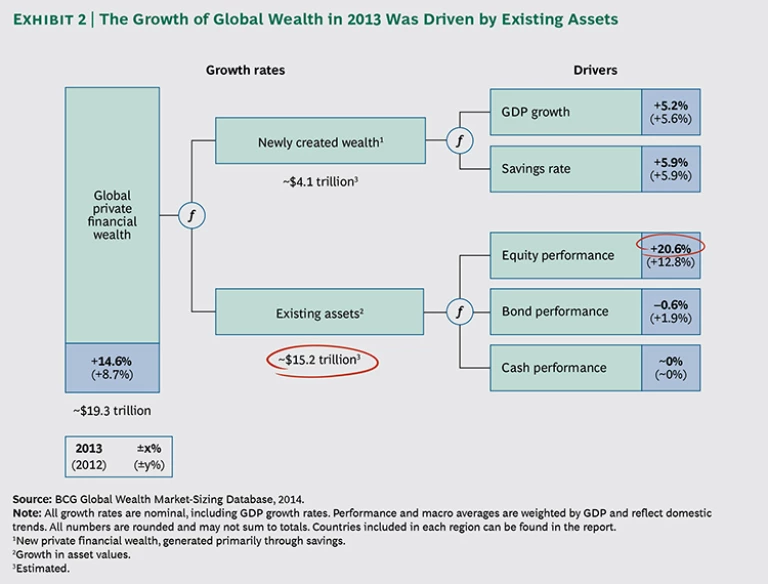

Globally, the growth of private wealth was driven primarily by returns on existing assets. (See Exhibit 2.) The amount of wealth held in equities grew by 28.0 percent, with increases in bonds (4.1 percent) and cash and deposits (8.8 percent) lagging behind considerably. As a result, asset allocation shifted significantly toward a higher share of equities.

Currency developments were more relevant to private wealth growth in 2013 than in 2012. Driven by the slowdown in quantitative easing, the U.S. dollar gained value against many currencies, particularly those in emerging markets, as well as against the Japanese yen.

As in previous years, strong growth in gross domestic product (GDP) in RDEs was an important driver of wealth. The BRIC countries, overall, achieved average nominal GDP growth of nearly 10 percent in 2013.

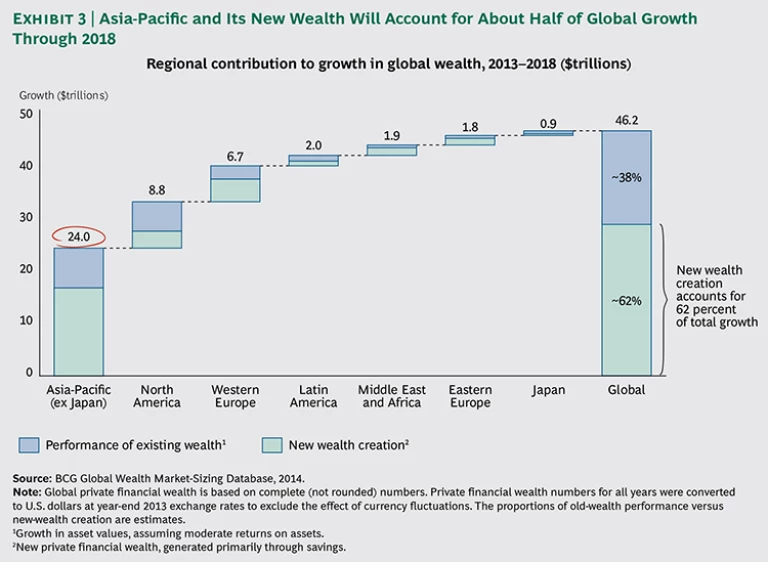

Looking ahead, global private wealth is projected to post a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 5.4 percent over the next five years to reach an estimated $198.2 trillion by the end of 2018. The Asia-Pacific region and its new wealth will account for about half of the total growth. (See Exhibit 3.) Continued strong GDP growth and high savings rates in RDEs will be key drivers of the rise in global wealth.

Assuming constant consumption and savings rates, North America will fall to a position as the second-largest wealth market in 2018 (a projected $59.1 trillion), being overtaken by Asia-Pacific (excluding Japan) with a projected $61.0 trillion. Western Europe should follow with a projected $44.6 trillion.

Millionaires

As the debate over the global polarization of wealth rages on, one thing is certain: more people are becoming wealthy. The total number of millionaire households (in U.S. dollar terms) reached 16.3 million in 2013, up strongly from 13.7 million in 2012 and representing 1.1 percent of all households globally. The U.S. had the highest number of millionaire households (7.1 million), as well as the highest number of new millionaires (1.1 million). (See Exhibit 4.) Robust wealth creation in China was reflected by its rise in millionaire households from 1.5 million in 2012 to 2.4 million in 2013, surpassing Japan. Indeed, the number of millionaire households in Japan fell from 1.5 million to 1.2 million, driven by the 15 percent fall in the yen against the dollar.

The highest density of millionaire households was in Qatar (175 out of every 1,000 households), followed by Switzerland (127) and Singapore (100). The U.S. had the largest number of billionaires, but the highest density of billionaire households was in Hong Kong (15.3 per million), followed by Switzerland (8.5 per million).

Wealth held by all segments above $1 million is projected to grow by at least 7.7 percent per year through 2018, compared with an average of 3.7 percent per year in segments below $1 million. Ultra-high-net-worth (UHNW) households, those with $100 million or more, held $8.4 trillion in wealth in 2013 (5.5 percent of the global total), an increase of 19.7 percent over 2012. At an expected CAGR of 9.1 percent over the next five years, UHNW households are projected to hold $13.0 trillion in wealth (6.5 percent of the total) by the end of 2018.

Wealth managers must develop winning client-acquisition strategies and differentiated, segment-specific value propositions in order to succeed with HNW and UHNW clients and meet their ever-increasing needs.

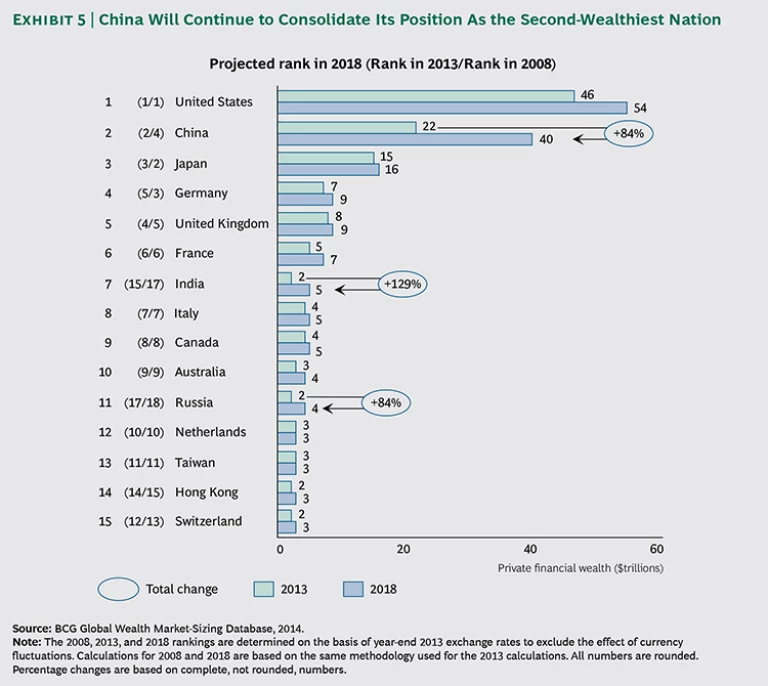

Regional Variation

Strong equity markets helped countries in the old world, which have large existing asset bases, to match the rapid growth in assets in the new world, which relies more on new wealth creation spurred by GDP growth and high savings rates. For example, private wealth grew by double digits in the U.S. and Australia, while some emerging markets, such as Brazil, showed substantially weaker growth. China will continue to consolidate its position as the second-wealthiest nation, after the U.S. (See Exhibit 5.)

North America.

The amount of wealth held in equities in North America grew by a robust 29.1 percent, compared with increases of 3.6 percent for bonds and 5.1 percent for cash and deposits. The strong performance of stocks was achieved despite worries about the so-called fiscal cliff at the beginning of the year and the tapering in quantitative easing toward the end of the year. Positive factors included an improving job market in the U.S. and a stabilizing economic outlook in Europe.

With a projected CAGR of 3.3 percent, private wealth in North America will reach an estimated $59.1 trillion by the end of 2018. The majority of this growth will come from existing assets rather than from new wealth.

Western Europe.

The extent of economic recovery in Western Europe varied across the region. Some countries outside the euro zone showed signs of steady recovery, with good-to-moderate nominal GDP growth rates (3.5 percent in the U.K., 2.5 percent in Sweden, and 1.9 percent in Switzerland). However, except for Germany (2.3 percent), GDP growth in the euro zone remained hindered by the lingering downturn, illustrated by France (1.2 percent), Italy (–1.0 percent) and Spain (–0.1 percent).

Since stocks in all major markets performed strongly, growth in private wealth was highest in countries with a relatively high share of equity allocation. These included Switzerland (wealth growth of 10.4 percent, equity share of 38.4 percent) and the U.K. (wealth growth of 8.1 percent, equity share of 49.3 percent). Switzerland also remained a top destination for wealth booked offshore. (See “Trends in Offshore Banking.”) Countries with lower equity allocations benefited less from stock market rallies. These included France (wealth growth of 5.5 percent, equity share of 23.0 percent) and Italy (wealth growth of 0.7 percent, equity share of 9.5 percent).

TRENDS IN OFFSHORE BANKING

Private wealth booked across borders reached $8.9 trillion in 2013, an increase of 10.4 percent over 2012 but below the increase in total global private wealth of 14.6 percent. As a result, the share of offshore wealth declined slightly from 6.1 percent to 5.9 percent.

Offshore wealth is projected to grow at a solid CAGR of 6.8 percent to reach $12.4 trillion by the end of 2018. The offshore model will continue to thrive because wealth management clients—particularly in the high-net-worth (HNW) segment, with at least $1 million in wealth, and in the ultra-high-net-worth (UHNW) segment, with at least $100 million—will continue to leverage the differentiated value propositions that offshore centers provide. These include access to innovative products, highly professional investment and client-relationship teams, and security (most relevant for emerging markets). Indeed, the latest tensions between Russia and Ukraine, as well as the escalated conflict in Syria, have highlighted the need for domiciles that offer high levels of political and economic stability.

In 2013, Switzerland remained the leading offshore booking center with $2.3 trillion in assets, representing 26 percent of global offshore assets. (See the accompanying exhibit.) However, the country remains under heavy pressure because of its significant exposure to assets originating in developed economies—some of which are expected to be repatriated following government actions to minimize tax evasion.

In the long run, Switzerland’s position as the world’s largest offshore center is being challenged by the rise of Singapore and Hong Kong, which currently account for about 16 percent of global offshore assets and benefit strongly from the ongoing creation of new wealth in the region. Assets booked in Singapore and Hong Kong are projected to grow at CAGRs of 10.2 percent and 11.3 percent, respectively, through 2018, and are expected to account collectively for 20 percent of global offshore assets at that point in time.

Overall, repatriation flows back to Western Europe and North America, in line with the implementation of stricter tax regulations, will continue to put pressure on many offshore booking domiciles. Reacting to these developments, private banks have started to revisit their international wealth-management portfolios. Some have acquired businesses from competitors—through either asset or share deals—while others have decided to abandon selected markets or to serve only the top end of HNW and UHNW clients. The goal is to exit subscale activities in many of their booking centers and markets, and in so doing to reduce complexity in their business and operating models.

Nonetheless, players that have decided to leave selected markets have not always obtained the results they hoped for. An alternative and potentially more effective course of action—one already embraced by some leading players—would be to establish an “international” or “small markets” desk that addresses all non-core markets.

The key to success is to clearly differentiate products and service levels by market and client segment. For core growth markets, full-service offerings that include segment-tailored products (including optimal tax treatment) should be featured. All other markets (and client segments) should be limited to standard offerings.

Equities continued to perform positively after the European Central Bank pledged to do “whatever it takes” to save the euro and launched the Outright Monetary Transactions (OMT) program in the second half of 2012. With a projected CAGR of 3.3 percent, private wealth in Western Europe will grow to an estimated $44.6 trillion by the end of 2018.

Eastern Europe.

Private wealth grew at a slower rate in the more central European countries, such as Poland (9.8 percent), the Czech Republic (4.4 percent), and Hungary (3.6 percent).

With a projected CAGR of 10.7 percent, the highest rate of all the regions, private wealth in Eastern Europe will grow to an estimated $4.5 trillion by the end of 2018. This forecast assumes that the current tensions between Russia and Ukraine will be resolved peacefully in 2014.

Asia-Pacific (excluding Japan).

For China, the remarkable 49.2 percent growth in private wealth was driven mainly by products such as PRC trusts (up 81.5 percent), reflecting the country’s rapidly expanding shadow-banking sector. Stock markets in China posted below-average performance, however, falling by 6.8 percent. This decline was influenced by increasing concerns about the country’s economic outlook after the government announced that it would accept lower growth rates to make its economic model more balanced and sustainable.

With a projected CAGR of 10.5 percent, private wealth in the overall region will expand to an estimated $61.0 trillion by the end of 2018. At this pace, the region is expected to overtake Western Europe as the second-wealthiest region in 2014, and North America as the wealthiest in 2018.

Japan. At constant exchange rates, private wealth in Japan rose by a modest 4.8 percent to $15.0 trillion in 2013. If the weakening yen is taken into account, however, private wealth in U.S. dollars was lower in Japan in 2013 than in 2012. That said, the weaker yen supported the Japanese export sector and led to an increase in nominal GDP growth from 0.5 percent in 2012 to 1.0 percent in 2013.

Japanese stock markets continued to perform extremely well, gaining 55.1 percent in 2013, spurred by the generally positive outlook for equities globally, the yen depreciation, and fiscal stimulus programs initiated by the government to fight deflation.

The amount of private wealth held in equities grew by 16.3 percent, compared with 1.8 percent for cash and deposits and a fall of 11.4 percent for bonds (continuing a downward trend). With a projected CAGR of 1.2 percent, the lowest rate of all the regions, private wealth in Japan will grow to an estimated $15.9 trillion by the end of 2018.

Latin America.

Below-average growth was observed in the larger countries in the region. Private wealth rose by 10.7 percent in Mexico and 5.6 percent in Brazil (where it was up 14.1 percent in 2012), driven by a weakening of local bond and stock markets.

Regionwide, riding developments in other regions, the amount of private wealth held in equities rose strongly by 19.6 percent, compared with 9.4 percent for bonds and 10.4 percent for cash and deposits. There were significant differences between the changes in onshore wealth (up 7.1 percent) and offshore wealth (up 23.5 percent)—attributable mainly to net inflows from countries such as Argentina and Venezuela and attractive returns from offshore investments.

With a projected CAGR of 8.8 percent, private wealth in Latin America will reach an estimated $5.9 trillion by the end of 2018.

Middle East and Africa.

As in all other regions, equities were the strongest contributor. The amount of wealth held in equities rose by 30.5 percent across major MEA markets, compared with 6.4 percent for bonds and 5.7 percent for cash and deposits. With a projected CAGR of 6.5 percent, private wealth in the region will reach an estimated $7.2 trillion by the end of 2018.

Finding the Optimal Business Model

Wealth managers globally embrace a host of different business models in pursuit of profitable growth. And although many players have an international presence regardless of their home market, their perspective on the optimal business model can vary by region, as we explore below.

The United States

Wealth management business models in the United States (and Canada) have been converging, but they continue to have differentiating features. A few hybrid firms are emerging that combine attributes of different models, particularly with respect to the offering and service model for the sizable HNW segment.

Essentially, there are five core models in practice in the United States: retail banks, online brokerages, registered investment advisors, full-service brokerages, and pure private banks.

Retail Banks. These institutions focus primarily on the mass affluent segment, relying on their branch footprint for customer acquisition. They generally provide a highly standardized product and service offering, with lead products such as enhanced deposit accounts and mutual funds. These models tend to be brokerage driven, with some face-to-face financial advisory available inside the retail banking branch.

We have observed a renewed effort by a number of retail banks using this model to increase their share of wallet among mass affluent customers. Some have even created dedicated suites within branches to create a distinctive service experience for such clients. Yet despite obvious cross-selling opportunities, most players have struggled to effectively combine retail banking and wealth management, and many of these efforts have failed to achieve the hoped-for results. Those institutions that have succeeded have typically started with a clear alignment between the retail bank and the wealth management business, and have figured out how to get the teaming right between bankers and financial advisors. They have also gotten incentives right (to drive referrals), forged effective training programs to develop talent from within, and leveraged low-cost channels to serve less-profitable clients.

Online Brokerages. Institutions embracing this business model also focus primarily on the mass affluent segment, although many are scratching their way up toward the lower end of the HNW segment. These players, which include fully integrated 401(k) recordkeepers and asset-management firms, have enjoyed significant success in capturing the mass affluent IRA rollover market. They typically offer light levels of advisory and financial planning over the phone, with some branch-based consultation. They have also raised the bar for customer expectations by providing 24/7 service, and have been widely successful in capturing assets and taking share from traditional brokerages. They have built a threat to traditional private banks by aggressively adding capabilities and advisor resources in order to provide customized service as the assets and financial needs of their clients evolve. Of course, effective mass marketing that creates a strong brand is critical for success with this business model.

Registered Investment Advisors (RIAs). These often-niche firms concentrate on the mass affluent and HNW segments and constitute the fastest-growing wealth-management business model in the U.S. Such players depend heavily on referrals. They also put great emphasis on establishing both deep client relationships and a strong presence in local communities. A distinctive feature is their fiduciary standard of customer care (as opposed to a suitability standard). Their strategy and product offerings tend to be highly variable, based on the individual firm, and is typically grounded in customized investment advice, comprehensive financial planning, structured portfolios, and asset allocation. Their revenue model is fee-based, in line with their fiduciary standards.

RIA firms can come in large and small sizes. The fastest-growing are the larger ones, which are putting together an independent proposition with sophisticated product and technology offerings. Some of these firms have managed to bring a number of successful, high-end brokerage advisors into their fold. Increasingly, RIAs have commissionable portions of their books held at traditional broker/dealers—usually as they transition to a 100 percent fee-based structure—but also for certain products that are not optimal in the fee-based construct.

Full-Service Brokerages. There are many variations of this model, and the landscape has shifted more than that of other models over the past few years. The traditional notion of a commission-driven, transaction-oriented, sole broker still exists. But this model has continued to evolve, led primarily by the four largest brokerages. In addition, many regional broker/dealers are moving closer to a pure private-banking model. They are placing more emphasis on offering deeper client relationships (not just investment advice), comprehensive financial planning (not just one-time product sales), and advisor teams with well-defined roles (not just sole practitioners). They are also improving their client-segmentation efforts, creating more diversified advisory forces (in terms of age, gender, and ethnicity), and trying to achieve a standardized and well-managed client experience.

As this model has developed, banking products have been more commonly offered, such as those related to specialized lending needs. New focus has been placed on fee-based billing arrangements as well as on discretionary client mandates. Increasingly with this model, we are seeing a blurring of the fiduciary standard and the suitability standard—a convergence we expect to continue.

Currently, full-service brokerages are still struggling to achieve the economics of a traditional private-banking model. Payout ratios of higher than 40 percent are common, and “the grid” still drives compensation for advisors. Further, despite major efforts to broaden and deepen customer relationships, the primary client link is with the advisor, not the firm. These players thus continue to be plagued by a relatively high level of customer turnover, and advisors are still able to take a majority of their clients with them if they move to a new firm. Some are placing a renewed focus on leveraging technology to provide better, more frequent service to clients in order to keep pace with online brokers.

Pure Private Banks. The private-banking model, while small in the U.S., is slowly gaining share. These models, which vary in focus—from squarely on the HNW, UHNW, or family office segments, for example—remain highly profitable. The model centers on a holistic relationship that includes links to other businesses such as capital markets, commercial banking, or trust offerings.

Traditionally, private-banking models that are commercial-banking oriented have struggled to provide credible expertise from an investing perspective. Their focus has been more on banking, overall asset allocation, and intergenerational wealth transfer. Conversely, private-banking models that have a strong capital-markets capability are often perceived to have robust investment expertise and products—but not the necessary skills to develop holistic advisory relationships. As these models develop, we expect to see some combining of capabilities aimed at addressing comprehensive client needs more effectively.

Which of these business models will emerge as the most promising is still up for debate. But players in each model will need to refine their core skills in order to achieve meaningful differentiation.

Asia-Pacific

A key driver in the rise of private wealth in the Asia-Pacific region has been strong GDP growth over the past five years, especially in China, India, and Indonesia. Nonetheless, the economics for wealth managers have been challenging for several reasons.

First, virtually all international players have been vying for a slice of the wealth managed in offshore centers such as Singapore and Hong Kong, where competition is particularly intense. In addition, local commercial banks have entered the market, notably in the lower wealth bands (under $5 million), further raising competitive pressures. Finally, client-acquisition costs are extremely high, because relationship managers (RMs) with the experience required to attract, retain, and serve high-value clients are in relatively short supply, driving up compensation.

Yet several trends are reshaping this landscape. First, the rise of onshore wealth, driven by in-country GDP growth, is generating additional pools of wealth that can be targeted with more attractive economics and a lower level of competition than in traditional offshore models. For wealth managers, the average pretax profitability of onshore business is nearly double that of offshore business.

In addition, private wealth is now flowing to second- and third-generation families and individuals. This shift is expected to favor a product mix that is less reliant on transactional capital-markets products and more centered around longer-term, recurring-fee products such as funds, discretionary mandates, and wealth protection offerings.

Further, wealth managers in the Asia-Pacific region have developed better collaboration models with adjacent businesses such as capital markets, investment banking, and commercial banking. A key consequence has been far greater opportunity to expand relationships with HNW and UHNW clients into other lines of business, thereby spreading the costs of acquisition and retention. We have seen revenues stemming from collaboration among business lines reach as high as 35 percent of total revenues.

Finally, technology innovations that enable benefits such as deeper segmentation, data-driven lead generation and management, and multichannel integration are paving the way for business models that foster enhanced RM productivity and profitability.

These trends will have varying impacts on the business models currently used to serve wealth management clients in the Asia-Pacific region, including the following models:

- Investment banks or “one bank” players that serve UNHW individuals and their companies on both a personal and corporate level

- “Independent” private banks that differentiate by providing independent investment advice and independent sourcing of products

- Fund-based advisors that focus on access to fund products and discretionary portfolio management as their core value proposition

- Brokers that are closely connected to financial markets and that concentrate on highly transactional flow businesses

- Flow players that create competitive advantage through collaboration between the distribution networks of the private bank and the product creation capabilities of the investment bank

- Local commercial banks that have advantages on multiple fronts, ranging from access to a large base of customers to strong balance-sheet funding capabilities

Local commercial banks are benefiting from current trends by leveraging several attributes: extensive onshore presence, enabling privileged access to new sources of wealth; existing customer relationships in other divisions of the group, permitting lower acquisition costs; and larger scale, raising the amount of investment that can be dedicated to enhancing both productivity and the client experience.

Conversely, the other wealth-management models are leveraging their product manufacturing, advisory, and execution excellence to successfully position themselves.

As for which model ultimately will be the biggest winner, the jury is still out.

Offshore Europe

As the world’s largest offshore center, Switzerland must cope with numerous key industry dynamics. Wealth booked from new-world markets such as Asia-Pacific, the Middle East, and Latin America—currently about one-third of the total in Switzerland—will continue to grow. Wealth booked from the old world will continue to decline. And wealth booked onshore in Switzerland will grow at a very moderate rate, roughly 2 to 3 percent per year through 2018. In addition, regulatory scrutiny of offshore centers—and of Switzerland in particular, owing to its history and high profile—shows no signs of abating.

Of course, all European offshore centers share some common challenges. Client needs are ever more diverse and challenging to address. Competition is more intense. Trying to manage multiple service models, each with its own cost and revenue profile, has become more difficult than ever. Product proliferation has not slowed down. Dealing with multiple booking centers—each with its own client, product, and regulatory climate—presents multiple problems. Most offshore private banks today serve clients in more than 100 markets. In a word, the complexity of the industry has become a major issue. Reducing this complexity can provide opportunities for profitable growth.

To this end, offshore wealth managers in Europe need to narrow their focus. We see players exiting subscale, unprofitable booking centers and trying to develop scale in a few select markets and regions in which they serve clients. Overall, the credo should be to do just a few things, but do them well. Indeed, successful private banks will focus on fewer markets and fewer segments within those markets. There is clear proof that RMs who focus on a limited number of countries—reducing the number of regulatory regimes and RM certification requirements that they have to deal with, and increasing on-the-ground time in their core markets—generate better performance in terms of net new assets (NNA).

Wealth managers need to develop a clear view on their priority markets. They should categorize them as core-growth, opportunistic, passively serviced, exit, and the like. Such prioritization helps players forge highly customized investment strategies, tailored products, and deeper overall expertise for key markets, while maintaining a standardized approach for others. As a step toward such prioritization—especially when making the passively serviced approach more concrete—some players have established so-called international or small-markets desks. Indeed, players should not necessarily exit their “long tail” of markets completely. They just need to clearly identify those best left behind and those best kept with a lean, efficient service model with minimal resourcing and no further investment.

Looking ahead, maintaining a strong presence in key markets only, establishing a clear service model for each client segment, streamlining the product portfolio, and compensating RMs on the basis of their direct contribution to profitability (as opposed to solely on the amount of NNA or revenues that they bring in) will be positive steps for offshore players in Europe.

Onshore Europe

In Europe, successful onshore private banks have made explicit choices in their operating models in order to achieve superior profitability. They have forged highly segmented product and service offerings that are well aligned with client needs, and have reduced complexity in their portfolios with fewer and more transparent products. They have developed finely tuned investment engines with strong advisory processes as well as excellence in the front office (stemming from more management focus on this area than in the past).

Yet there are areas that still need attention for many players. A high level of sales force effectiveness needs to be became a permanent capability, not a one-off program as it has for some institutions. Some leading banks have installed a dedicated central team of private-banking champions who continuously drive tangible sales-force improvements across all desks—and strive to raise RM performance. In addition, the development of seamless, fully integrated multichannel capabilities needs a higher priority.

Some midsize players are seeking larger scale—as well as more efficient IT and operations—by leveraging captive retail-banking networks and their middle and back offices. They should be prepared, however, to outsource complete back-office activity to external (integrated) providers. A few larger players have already reached a high level of efficiency through dedicated lean initiatives and front-to-back optimization programs.

When it comes to raising profitability, most European onshore players have focused mainly on trying to optimize the top line, with less attention given to costs (although pressure on the cost side is still rising). To raise revenues, some players are concentrating heavily on refining client segmentation, including aligning cost-to-serve by segment, raising the number of basic products in lower wealth bands, increasing advisory capabilities in higher wealth bands, and leveraging dedicated experts—who are often involved in direct client meetings—to a greater degree.

Of course, every market has its own nuances, and a strategy that succeeds in one country may miss the mark in another. But going forward, many European onshore players need to take some common steps, such as focusing on select client groups, leveraging retail networks as feeder channels for new wealth-management clients, reviewing pricing structures, and cross-selling products such as mortgages to broaden the overall offering.

Many also need to address substandard scale (because IT investments and regulation favor larger players), centralize their expertise (while keeping coverage local), and explore digital solutions to a greater extent.

Latin America

Latin America has continued to show appreciable growth in private wealth. Assets are slowly gravitating back to equities in the wake of a shift toward money market investments triggered by the 2008–2009 crisis. A current trend involves local players attempting to develop a regional presence that includes the ability to offer investment opportunities in the most attractive areas, particularly in Brazil and the Andean region.

Brazil. Although most major international wealth managers have developed a presence in Brazil—Latin America’s largest wealth market, and a predominantly onshore one—sophisticated local players, mostly universal banks, are the dominant institutions. While 2013 was a very challenging year, owing to a weak stock market and a decline in interest rates that affected fixed-income investments, wealth managers still managed to increase assets under management (AuM) by acquiring new assets.

In addition, many players have made progress in weeding out their long tail of small, unprofitable clients. This initiative may have hindered overall AuM growth but will lead in time to higher overall profitability. Brazilian banks generally have a higher minimum AuM threshold ($1 million to $2.5 million) compared with players in other Latin American countries ($500,000 to $1 million).

Despite short-term challenges, Brazil remains a structurally attractive market with healthy levels of return on assets (ROA) and profitability within reach. The country also has a favorable environment for wealth creation, with many entrepreneurs freeing up value that was previously locked inside family-run enterprises that are now transitioning to professional management. Moreover, international wealth managers are showing no signs of slowing their investments aimed at gaining a firmer foothold in Brazil.

Mexico. Mexico is also a fast-growing and attractive wealth-management market. Its onshore business and broader overall offering have evolved in tandem with the country’s relative economic stability.

Mexico’s onshore business is dominated by large universal banks, followed by brokerage houses and independent advisors. Some of the larger players are retooling their offerings while smaller players are generating growth with low-cost models or niche propositions.

The Mexican market has become more and more sophisticated, as evidenced by its stronger international profile, broader range of investment opportunities, and increasingly demanding clients. Some players have started to develop buy-side, open-architecture offerings.

Offshore business is mostly characterized by RMs who fly in and out to acquire clients but who are not based in the country—in many cases combined with a representative office or a consulting license. There are roughly ten offshore incumbents, some with plans to launch an onshore offering. In addition, more than 35 offshore institutions are acting as niche players with low-touch models, each managing between about $1 billion to $3 billion in AuM.

Chile. Relative macroeconomic stability and healthy GDP growth are driving wealth creation in Chile, which like Brazil and Mexico is predominantly an onshore market. The UHNW segment accounts for nearly 40 percent of AuM held by wealthy households. Family offices are key in this segment and have developed increasingly sophisticated capabilities.

Local players (mainly investment banks, commercial banks, and asset managers) have competitive onshore offerings—and also provide offshore options. They have been challenged lately by the emergence of multifamily offices that promise objective buy-side advice. In addition, recent disappointing local stock-market returns combined with a weaker currency represent a call to action for domestic players. A buy-side proposition that includes the capacity to provide offshore advice as well as the opportunity to invest in the high-growth markets of the region could constitute an attractive offering for the wealthy.

Colombia and Peru. Both Colombia and Peru are sizable enough to matter, and are among the fastest-growing markets in the region. Both are largely offshore but are developing increasingly relevant onshore offerings. Healthy returns in local markets and greater economic stability are positive forces, favoring the development of onshore offerings. In Peru, well-established, sophisticated, and highly visible local players also hold a relevant share of offshore assets. In Colombia, portions of the recent tributary reform that address tax evasion will generate new challenges to the offshore business—and are likely to spur the development of a more meaningful onshore market.

Overall, wealth managers in Latin America will need to further explore ways to differentiate their offerings from those of players in other attractive emerging markets.

Methodology

BCG has developed a proprietary methodology, which has been continuously refined and enhanced over the past 14 years, to measure the size of global wealth markets.

Our definition of wealth includes the amount of cash, deposits, and listed securities held either directly or indirectly through managed funds and life and pension assets. Such assets can typically be monetized easily. Other assets, more difficult to monetize and thus excluded, include any real estate (primary residence as well as real estate investments), business ownerships, and any kind of collectibles, consumables, or consumer durables such as luxury goods.

The market-sizing model of Riding a Wave of Growth: Global Wealth 2014 covers 63 countries accounting for more than 95 percent of global GDP (real GDP in U.S. dollars at 2005 constant prices). For the year 2013, we calculated personal financial wealth for 43 large countries (about 91 percent of global GDP) through a review of national accounts and other public records. For an additional 20 smaller countries (about 5 percent of global GDP), we calculated wealth as a proportion of GDP, adjusted for country-specific economic factors.

We then distributed total wealth within each country by household (not by individuals or adults) on the basis of a proprietary Lorenz curve methodology. These curves were based on a combination of wealth distribution statistics for countries that had available data. For countries without such data, we developed estimates on the basis of wealth distribution patterns of countries with similar income distributions (Gini coefficients) compiled by the World Bank. We further refined the wealth distribution using other public sources such as “rich lists” and BCG proprietary information.

We used available national statistics to identify different asset-holding patterns for the individual wealth segments in each country. When such data could not be obtained, we assumed that countries with similar cultures and regulatory environments would have similar asset-holding patterns. Finally, we calculated market movements as the weighted-average capital performance of asset classes held by households in each country, factoring in domestic, regional, and international holdings.

Acknowledgments

For their valuable contributions to the conception and development of this report, our special thanks go to the following BCG colleagues. Asia-Pacific: Ashish Garg, Vish Jain, Kuo-Loon Loh, Masahide Ohira, Sangsoon Park, Perry Peng, and Sam Stewart.

Europe, Middle East, and Africa: Peter Adams, Carsten Baumgärtner, Thorsten Brackert, Stefan Dab, Mirjam de Meij, Guido Crespi, Ákos Demeter, Dean Frankle, Jérôme Hervé, France Joris, Til Klein, Kai Kramer, Ludger Kübel-Sorger, Reinhold Leichtfuss, Benoît Macé, Andy Maguire, Santiago Mazón, Martin Mende, Tim Monger, Edoardo Palmisani, Vit Pumprla, Stuart Quickenden, Monica Regazzi, Jürgen Rogg, Olivier Sampieri, Michael Schachtner, Christian Schmid, Pablo Tramazaygues, Claire Tracey, Jeroen van de Broek, and Ian Wachters.

Americas: Ashwin Adarkar, Patricio Amador, Andres Anavi, Eric Brat, David Bronstein, Nan DasGupta, Monish Kumar, Enrique Mendoza, Joel Muñiz, Neil Pardasani, Gary Shub, Steve Thogmartin, Masao Ukon, Joaquín Valle, Yves Wetzelsberger, and André Xavier.

Core global wealth team (Switzerland): Annette Pazur, Erik Schmidt, and Adrian Lüthge.