The postcrisis financial environment has prompted financial services organizations to embrace lean management as a way to become more agile and efficient—and ultimately more responsive to an increasingly demanding and choice-rich client base. But although companies are embracing lean more than ever, a 2014 global survey of roughly 30 financial institutions conducted by The Boston Consulting Group found that most fail to achieve the total potential value from their transformations.

Read more on this topic

Lean That Lasts: The Series

- Capturing the Full Potential

- Embarking on the Journey

- Transforming Financial Institutions

The data showed that most improvement initiatives fall short of their intended goals. Among the financial services organizations surveyed, only 40 percent of lean transformations captured targeted financial benefits, and just 30 percent of our survey respondents realized the desired qualitative benefits. Given the scale of many lean programs, this performance gap represents a significant loss of value in terms of investment resources and opportunity cost that banks cannot afford to squander in a period of tightening margins and intensifying competition.

Lean programs can stumble for a number of reasons, including an ill-defined scope or weak grasp of the steps needed to start and scale up the program. (See Lean That Lasts: Transforming Financial Institutions , BCG Focus, September 2012, and Lean That Lasts: Embarking on the Journey , BCG Focus, October 2013.) However, one of the least discussed but most important factors is an insufficient understanding of the role that culture change plays in the journey to become a world-class lean organization. This is particularly true in financial services—an industry in which complex hierarchical structures and silos can impede customer responsiveness and weaken the incentive and momentum for change.

Neglecting the importance of culture change is a missed opportunity. BCG research shows that financial services companies that succeed in infusing a lean mind-set into the DNA of their organizations can deliver efficiencies and cost savings of more than 35 percent and improve customer service and cycle times by more than 50 percent.

The Importance of Culture Change

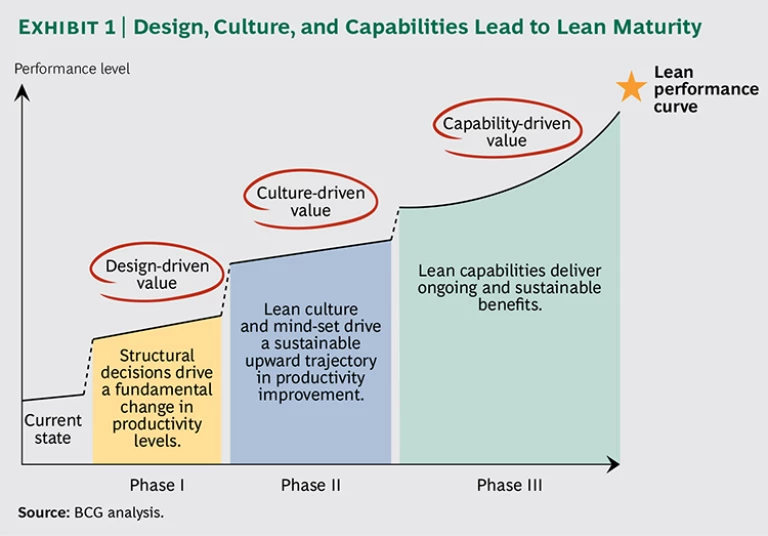

Institutions typically go through several phases of maturity with respect to their lean programs. Value is often initially driven by process redesign and coordinated by a centralized team. Ramping up from there, however, requires a high-performing culture that can expand the improvement mandate so that all employees feel part of the process and the changes become “business as usual.” When that happens, employees become more invested in the program and the skill base broadens across the company—qualities that embed organizational capabilities and help sustain lean gains long after the formal transformation effort concludes. (See Exhibit 1.)

BCG research shows that financial services organizations that define their target culture and the mechanisms to achieve it as part of their lean program are far more likely than those that don’t to ensure that gains from lean last over time. That’s because behavior and attitude establish the context for change. Although systems and processes often feel more tangible and easier to refine, it is the soft cultural elements—such as how to lead, manage, and foster collaboration—that serve as the organizational glue needed to make lean improvements stick and elevate the performance curve.

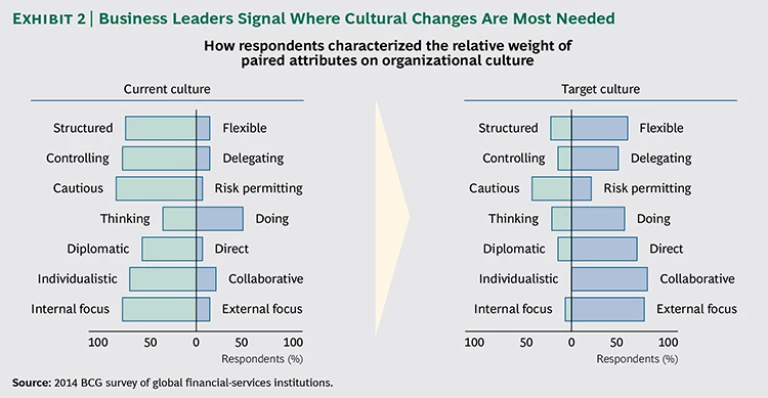

The problem is that while business leaders recognize the importance of culture change in propelling and sustaining high performance, BCG research shows that relatively few address it in the early stages of the transformation. Although the majority of respondents indicated that they believe culture change accounts for 20 percent of a transformation’s total value, only one-third of respondents factor it into their program and only one-quarter indicated that employee satisfaction and engagement were specific program objectives. Despite this paradox, participants broadly agree on the cultural characteristics most likely to yield a successful outcome—including a collaborative, flexible, customer-centric environment. (See Exhibit 2.)

To establish that culture, organizations have to take the following three steps:

- Authorize and support independent decision making. The real-time requirements of today’s business environment make anticipating and responding to issues in ways that improve the customer experience essential for competitive success. For that reason, employees need the authority to solve problems on behalf of the customer without jumping through lots of internal hoops. Organizations that establish a broad delegation of decision-making authority are more likely to experience improved employee buy-in and more widespread adoption of the lean program mandate. In most financial-services organizations, decision-making authority remains concentrated in the hands of a few—a by-product of complicated hierarchical structures that often shift power to informal networks driven by those perceived as closest to the customer.

- Ensure openness to experimentation. Lean is based on the idea of continuous improvement, rapid iteration, and experimentation. That can happen only in a business environment that is supportive of trial and error. In a lean culture, managers and employees fail not when they make mistakes but rather when they don’t make an effort to pitch in to find a solution that works. Adopting that perspective requires real behavioral change.

- Insist on shared accountability paired with the right incentives. In many organizations, it can be tempting to assign blame to a department or individual when an issue arises. If a new credit or payments system encounters a glitch, for example, it can be reflexive to point the finger at IT, while others wash their hands of the problem. But that rarely ends up solving a problem optimally and often reinforces silos at a time when customer needs are increasingly interdisciplinary. In a high-performance lean culture, all those who touch a process have some responsibility for designing it and fixing it. But for employees to feel comfortable experimenting and refining, they need managers who play the role of coach instead of disciplinarian—and they need shared accountabilities so that everyone is invested in the same outcome. For that to happen, managers must provide the right incentive structure so that employees are naturally inclined to align their behavior with the desired outcomes.

Providing appropriate growth opportunities is also important, because employees are more likely to contribute when they feel as though their full range of talents and abilities are being used. When those pieces are in place, lean initiatives can deliver a two-for-one benefit, improving both employee satisfaction and the customer experience.

The Major Lean Bottlenecks

Because of their role in overseeing progress and remediating bottlenecks, middle managers—those closest to the ground on day-to-day operations—often provide the most critical support for lean success. Yet close to 90 percent of all respondents said that gaining middle-manager engagement in the lean transformation was a major challenge. That lack of buy-in can create a troublesome leadership vacuum.

More than 70 percent of respondents identified poor planning and communication as additional factors that contributed to the limited uptake and delivery of their lean program. Infrequent or unclear communication can leave employees confused about the mission and doubtful about the organization’s long-term commitment and ability to deliver on the stated strategy. Other obstacles to success include a lack of planning with regard to culture change and a transformation that is too slow or too limited in scale.

Such problems are not unique. For example, as part of its change agenda, the sales team at one financial institution was charged with driving greater cross-selling. But poor cooperation among different business units caused managers to miss their targets. A closer look revealed that incentive compensation was awarded based on the profit and loss of an individual’s business line, leaving little motivation for departments to partner across divisions. In addition, weak knowledge-sharing processes limited collaboration potential even when individual managers sought to partner. Although senior management had voiced its backing during the company’s “town hall” meeting, there was little visible involvement from them thereafter. Most of the responsibility for pushing through the needed changes fell on middle managers. But without a unified strategy from top leadership, many felt that the change agenda lacked credibility. In addition, a laundry list of KPIs and sometimes conflicting departmental goals beween credit and risk made that strategy difficult to implement. As a result, middle managers were uncomfortable taking the risk of deploying new initiatives, and many of the original problems persisted.

How to Change Behavior

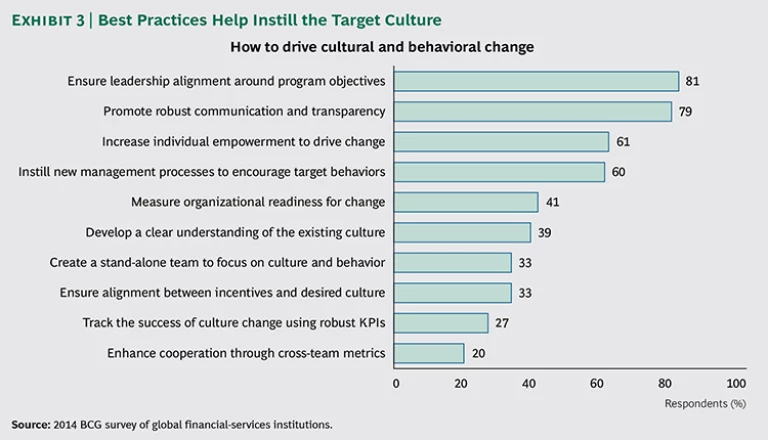

BCG research revealed the best practices needed to instill the target culture. (See Exhibit 3.) Many of these underscore our finding that successfully changing behavior requires moving beyond the traditional change-management approach of tackling feelings and mind-sets—abstract notions that can trigger people’s defense mechanisms and lead to tacit compliance—to instead focus on creating an organizational context for change that makes lean behavior an individually useful behavior. Establishing that organizational context for change requires four things: a mutual-engagement model; a strong lean-management system; meaningful, performance-based incentives; and effective formal training.

-

Mutual-Engagement Model. A mutual-engagement model is important because change programs work best when all players feel as though they have a voice in the process, especially those tasked with executing the key elements and rallying the support of front-line employees. When midlevel managers are fully aware of the nature of the planned change and how it is likely to affect their team and role, they are more likely to buy in to the change and be persuasive in encouraging their teams to do the same.

Using the mutual-engagement model, lean managers coach direct reports. Rather than dictate actions, they ask guiding questions. Putting themselves in a role akin to that of a facilitator encourages their teams to develop their own solutions. And lean managers carefully track KPIs and work with teams to identify potential interventions in areas where progress lags. With the right checks and balances, lean adopters can distribute responsibilities to lower levels and establish new decision rights for those down the line. In that way, managers—with sustained backing from leadership—can bridge the gap between strategy and execution.

-

Strong Lean-Management System. The mutual-engagement model must be backed by a lean management system to create a culture of open information flow and fact-based decision making. Best practice is characterized by frequent interactions, close coordination, and focused communication. Quick status meetings or team “huddles” at the beginning and end of each day are key. So, too, are “gemba walks,” in which managers get out from behind their desks and spend time in operational areas. Such daily interactions allow for timely identification of pertinent issues and provide a channel for real-time problem solving. By “walking the talk,” managers show their commitment to the change process. Senior management’s participation in huddles and walks is especially powerful—particularly during the launch phase—both to underscore the organization’s backing and to provide middle management with the resources and coaching needed.

The use of visual management such as charts and dashboards allows busy professionals to get an at-a-glance understanding of progress and flag bottlenecks in a way that makes it easier to engage leadership’s attention. Whiteboards and on-site tools also facilitate coordination. Staff can check in during the course of a day to refine desired outcomes, register tasks completed, or note new ideas. In addition, managers can use such data as a tangible way to celebrate performance.

-

Meaningful, Performance-Based Incentives. Performance measurement and incentives serve as a critical tool, both to ensure that the transformation stays on track and to foster engagement and collaboration. Shared accountability and a narrow set of strategically aligned performance metrics are especially important. Financial services organizations can help crack internal monopolies and unproductive behaviors such as deal hoarding and clique building by setting rich, cross-team objectives with joint accountabilities. That encourages reciprocity and gives management the means to increase rewards for those who co-operate and consequences for those who do not.

Lean financial-services organizations establish common, long-term, cross-organizational goals and performance metrics. With the emphasis on quality over quantity, the best lean programs focus on a handful of metrics with an end-to-end view instead of many metrics with limited use and diluted impact. Peer input also plays an increased role in performance reviews. This serves as a catalyst to encourage desired teamwork. Some institutions make a point of reinforcing “integrators,” who, in lean terms, are people with the ability to work across silos—a quality that makes them powerful change agents. Leading lean adopters reward integrators with more authority. The increased clout creates a virtuous circle as others seek to emulate those behaviors and grow into similar high-profile roles.

- Effective Formal Training. Proper training is essential. Some organizations set up formal lean-management academies internally. But formal classroom training must be accompanied by hands-on learning and real-time application. Otherwise, what’s taught remains too abstract and divorced from day-to-day realities. One large bank, for instance, convened a training program offsite for managers of managers—a sizable investment to support the lean program. During theory sessions, participants quickly agreed on the culture and management style that would be most effective for their organization. Yet when asked to put these skills into action during the practical case study that followed, two-thirds defaulted to their typical management style. Stories such as these underscore why real behavioral change requires the contextual reinforcement that comes from on-the-job application.

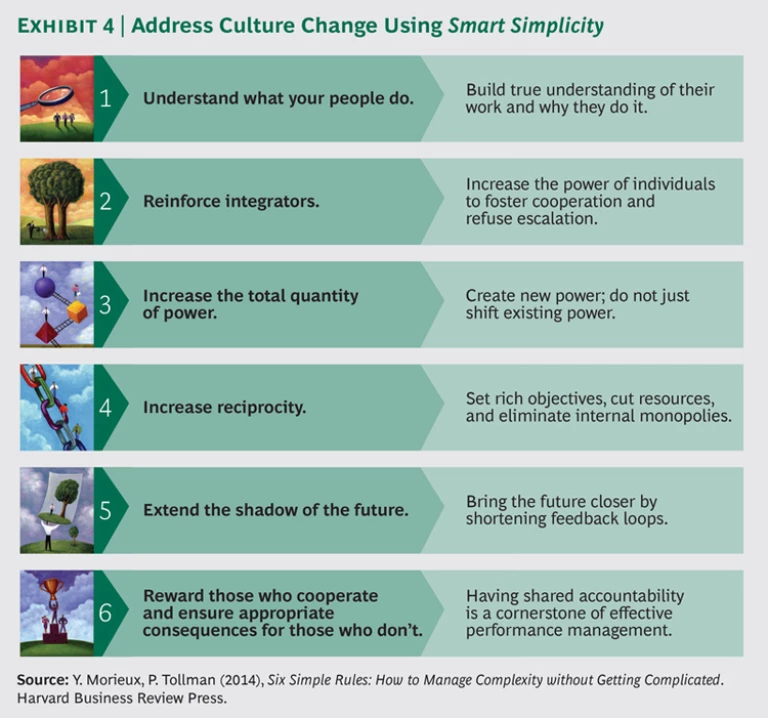

To help establish the organizational context for lean, companies can use BCG's Smart Simplicity rules: understand what your people do, reinforce integrators, increase the total quantity of power, increase reciprocity, extend the shadow of the future, and reward those who cooperate. (See Exhibit 4.)

When to Address Behavior Change

Behavioral-change objectives should be discussed during the planning stages of the lean program, even if the specific actions related to them are phased in later. Incentives, measurement systems, professional development, and the physical environment are all necessary elements in the transformation process. The organization can then determine the right time to implement those elements based on its strategy and situation.

During the planning phase, teams lay out their strategic goals and determine the range of process and behavioral changes needed to implement them. For instance, the first wave of a target operating-model transformation might seek to shorten credit approval times or streamline the account-opening process. To achieve those objectives, the lean program team would examine current processes, such as the degree of automation, and the cultural changes required to support target behaviors—including changing team structures to encourage collaboration, cutting back the number of performance metrics, and integrating lean-performance milestones into employee compensation reviews.

With the plan in place, organizations can decide when and how to implement the combined strategy. Some like to start with the behavioral-change piece in order to build a common platform to support the transformation. Others begin with a pilot to give managers and employees proof of concept. Still others combine the behavioral-change plan with the pilot—an approach that often accelerates the transformation but requires the biggest up-front investment of time and financial resources. No matter how an organization chooses to sequence its implementation, the behavioral dimension must be factored into the planning and embedded into the rollout.

Organizations frequently underestimate the importance of establishing a strategically aligned culture as part of their lean transformation. Cultural alignment provides employees with the autonomy to act in accordance with company objectives and without constant management oversight. It also creates clear expectations. Financial services organizations that secure visible and sustained commitment from top management and involve all levels of the organization are more likely to see their lean transformations stick. They ensure that teams are resourced adequately, that the right skill sets are in place, and that time is carved out for teams to execute the program. They recognize that all parties must understand their respective requirements and the metrics that constitute success. And they know that frequent check-ins serve as the connective tissue to track performance and build support.

In short, organizations that see cultural dynamics less as an afterthought and more as an intrinsic part of the lean transformation process are significantly more likely to have their efforts succeed. Such success will fundamentally enrich shareholder value through happier customers, highly engaged employees, and sustained (even accelerated) productivity gains.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge those colleagues who made important contributions to this report: Christophe Duthoit, Brad Henderson, Yves Morieux, Michael Shanahan, Niclas Storz, and Juliet Grabowski.

They would also like to thank Marie Glenn for her help with the writing of the report, as well as Katherine Andrews, Gary Callahan, Philip Crawford, Catherine Cuddihee, Sarah Davis, Angela DiBattista, Kim Friedman, Abby Garland, and Sara Strassenreiter for their help with editing, design, production, and distribution.