As global banking returns to overall profit for the first time since the financial crisis began, banks have entered a new era in which every region, product, and legal entity will be closely regulated.

This is not a onetime phenomenon. Hyperregulation is here to stay.

Global Banking Regains Economic Profitability

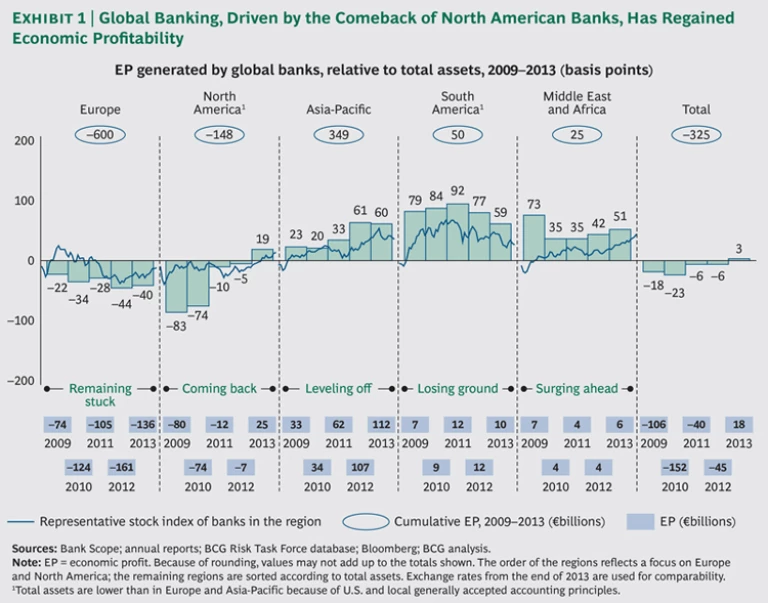

Banks, averaged globally, created positive economic profit (EP) of €18 billion, or 3 basis points as a percentage of total assets in 2013, compared with negative EP ranging from –6 to –23 basis points

The global increase in EP was driven by the positive regional performance of banks in North America as well as the Middle East and Africa, where banks continued to surge ahead. Banks in Asia-Pacific outpaced all other regions even as their performance plateaued. South American banks lost ground: their EP remained positive but shrank significantly for the second year in a row. In Europe, and only there, banks continued to deliver negative EP.

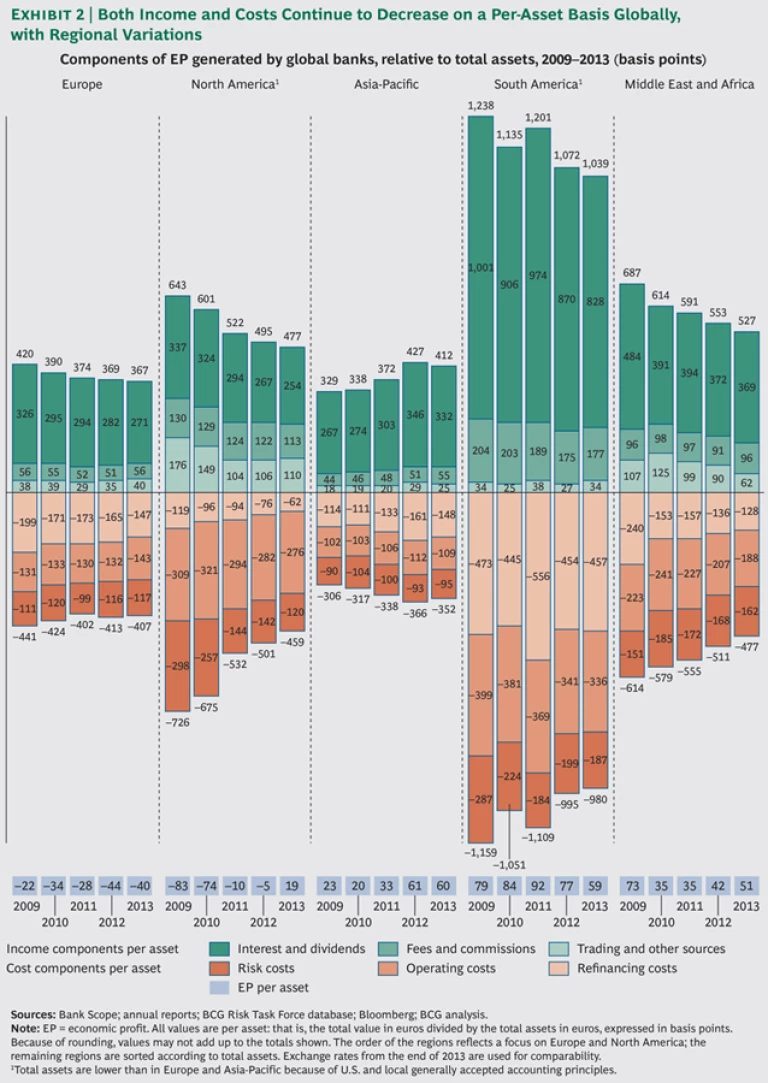

An assessment of the components of economic profit reveals the basis for these differences in regional performance and suggests paths banks might take to achieve positive value. (See Exhibit 2.)

Most notably, North American banks are again growing and producing sizable EP. Quantitative easing by the U.S. Federal Reserve helped reduce refinancing

Another driver of value creation was the decrease in risk costs due to an improved macroeconomic environment. With operating costs decreasing by only 2 percent on a per-asset scale, there is still room for further value creation. This is a prerequisite for North American banks to stay competitive. For this reason, both lean and delayering programs are high on the agenda of many banks.

- In Europe, and only there, banks continue to show little sign of recovery, delivering negative EP. In the medium term, refinancing costs are likely to rise in Europe, as European Central Bank (ECB) policy may shift. In order to escape persistent negative EP, European banks should focus on either the top line or the operating-cost base.

- The positive performance of banks in the Middle East and Africa, along with that of North America, helped drive the global increase in EP.

- Banks in Asia-Pacific outpaced all other regions in value creation, even as their performance plateaued. Many Asia-Pacific banks have done little to boost efficiency, however, particularly in the risk function, and they were not able to compensate for falling income. The new figures suggest that Asia-Pacific banks have yet to adapt fully to the region’s maturing market and possibly slowing growth pace.

- South American banks lost ground: their EP remained positive but shrank significantly for the second year in a row. In order to return to sustained EP growth, South American banks need to focus on efficiency, streamlining their organizations to match the changing risk profile of their business.

Worldwide, the new era of regulation will have an uneven impact on the various components of bank performance. As a consequence, some regions are in a better shape than others for addressing the shifting regulatory environment.

Managing the Transition

In the face of these circumstances, we believe, banks need a shift in mind-set. Regulation will not go away. Instead, banks must adopt a good-citizen approach to proactively addressing the broad intent of regulation .

This will demand a structural assessment of regulatory measures and a regulatory-target picture to identify the pressure points in a bank’s current setup. Using this approach, clear management options can be deduced and a regulatory roadmap designed.

This transition can be supported by establishing forward-looking management of the regulatory-project portfolio and putting in place a comprehensive control framework.

Three major steps help operationalize the management of the regulatory-project portfolio:

- Establishing a regulatory and findings baseline as a yardstick is crucial. This baseline should be comprehensive and forward-looking, enabling the bank to maintain a multiyear perspective.

- The bank should design and prioritize implementation measures in a way that links topics, content maturity, and minimum implementation time. This will require leading discussions about fundamental solutions. Mere fire fighting will not sustainably resolve the urgent issues of the new era.

- The budget demands of proposed implementation packages must be challenged on the basis of a predefined set of eligible reduction levers—for example, reducing the scope of bank activities, requirements, and obligations—and price reduction.

In order to ensure that all existing and new regulations and internal policies are strictly followed, banks should establish a comprehensive control framework based on the three-lines-of-defense (3LOD) model, which consists of business support, independent controls, and internal audit. This approach is crucial for reducing nonfinancial risks such as fraud, misconduct, and reputational damage, which, in most cases, have not been sufficiently considered. (See “Litigation: The New Cost of Doing Business.”)

LITIGATION: THE NEW COST OF DOING BUSINESS

The new era in banking is characterized by a rigorous enforcement of sanctions. As of September 2014, the cumulative litigation costs for EU and U.S. banks since the onset of the financial crisis had reached some $178 billion. (See the exhibit below.)

Most of the costs originated with U.S. regulators’ mortgage-related claims, and the remaining litigation costs are divided among claims focused on misselling, violations of U.S. sanctions, improper conduct, market manipulation, tax evasion, and misrepresentation. Litigation costs of banks headquartered in the U.S. leapt higher in 2011, driven by mortgage-related claims, which continue to dominate. EU bank costs were kick-started in 2012, beginning with redress payments for misselling payment protection insurance in the UK, followed by market manipulation issues—for example, those related to the London Interbank Offered Rate scandal—as well as improper-conduct litigation, such as anti-money-laundering cases.

The current wave of litigation cases has not yet been settled, and potential—still hidden—litigation risks are substantial. Meanwhile, regulators have shifted their view toward more unified and sanction-based supervision, adopting regulations with a stronger focus on business conduct.

All of these developments reflect the persistent character and future burden of litigation—a new cost of doing business.

In order to derive a state-of-the-art 3LOD model, banks have to fundamentally upgrade their control frameworks:

- Banks need to establish a comprehensive, up-to-date risk inventory reflecting all regulatory, business-conduct, and stakeholder requirements and clearly allocate responsibilities within the first and second lines of defense.

- Furthermore, the second line is responsible for defining a global control framework, specifying how best to adapt global standards to local needs and how to achieve a well-balanced, effective control intensity.

- On the basis of this global control framework, the first line of defense can build specific controls, driving the full integration into the bank’s operating model.

Although comprehensiveness and rigor are crucial, a pragmatic approach to implementation is typically even more important to success. This includes identifying the most important controls through group-wide risk-assessment standards, ensuring action-promoting outcomes of controls with a proper reporting framework, and reviewing the effectiveness of controls on a regular basis.

Enhancing Data and IT Capabilities

In this new reality, a major regulatory goal is the improvement of banks’ data and IT capabilities in order to ensure higher transparency levels and enhanced reporting within the industry.

To date, regulators have already pursued a variety of related measures, including in Europe the introduction of Common Reporting and Financial Reporting—harmonized reporting standards—by the European Banking Authority (EBA), the execution of the ECB’s Asset Quality Review (AQR) and the EBA’s EU-wide stress test, as well as the new and significant requirements of the ECB’s AnaCredit and the European supervisory authorities’ Supervisory Review and Evaluation Process.

While many of these regulations are intended to cover specific reporting, the BCBS 239 regulatory requirements constitute the overall umbrella. BCBS 239, published in January 2013, requires so-called global systemically important banks to comply with 14 principles by January 1, 2016.

A foundation has to be in place for risk data aggregation and reporting within banks:

- First, the required scope of reporting needs to be clearly defined and critically assessed. It should cover at least all risk reporting but may additionally cover all main types of reporting. On the basis of these, a comprehensive map should be created to identify the critical metrics needed to address existing and future regulation.

- Next, full transparency on the aggregation of specific critical metrics and their components, based on the map, should be established functionally, technically, and in terms of bank processes.

- Furthermore, data quality and data governance should be ensured. On the basis of the fully transparent decomposition of critical metrics, the bank can assign clear responsibility to components. Thus, data quality can be measured and tracked, leading to enhanced data-quality management.

- Finally, overall data quality and consistency of components used in reporting should be guaranteed on the basis of an overarching control framework.

With the basic foundation in place, data delivery capabilities must now be enhanced, raising several management options that need to be addressed. These include timelier reporting, a single-point-of-truth data infrastructure with the necessary data granularity and cross-functional data alignment, as well as enhanced automation.

An Opportunity, Not a “Necessary Evil”

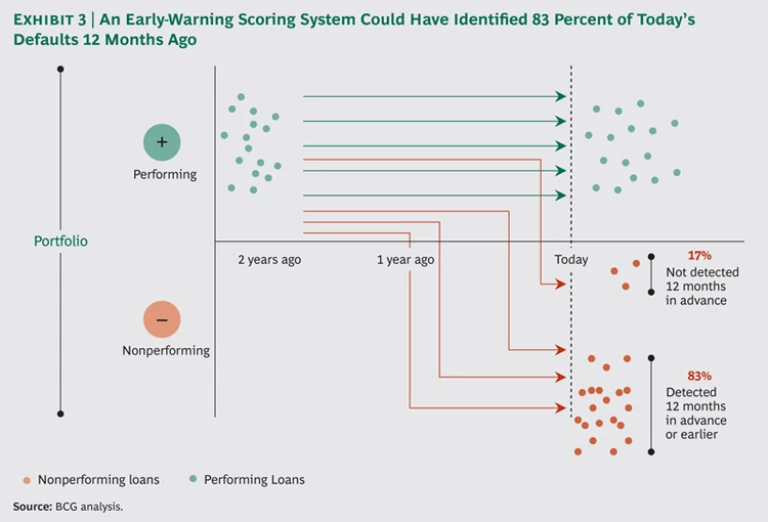

Given the expected pressure on the data and IT side to push transparency, banks could easily find themselves thinking about these as a necessary evil. However, that perspective fails to recognize the positive benefits that a transparent bank enjoys. For instance, better data and IT capabilities enhance quantitative analyses that help accelerate decision processes and make them more objective. One approach developed by BCG’s risk-analytics team involves setting up an early-warning scoring system to help detect credit events. BCG analyses show that early-warning scoring systems could have identified more than 80 percent of today’s defaults a year in advance. (See Exhibit 3.)

Furthermore, we expect a second-order effect of this push for transparency: the reappearance of M&A on the agenda. Especially in Europe—where the ECB’s AQR and stress tests bring an unparalleled transparency to banks’ balance sheets and capital situation—opportunities for portfolio deals or even full-scale cross-border and in-market M&A will arise.

Whichever approach a bank chooses, one thing is clear: each institution must find its own path to prevail in this era of relentless regulatory oversight, new standards of conduct, and rigorous enforcement. Success will require banks to redefine the very nature of risk, to move beyond their current control frameworks, and to embed new compliance thinking and systems into their operating model.

Total transparency is not just a mantra or marketing catchphrase for banks. Nor is it simply a new set of legal obligations and constraints. It will be a permanent and defining characteristic of banking institutions on the leading edge of change. Winning banks will be those that translate regulatory requirement and investment into strategic opportunity and commercial advantage. Navigating the new environment may demand nerves of steel. It will certainly require building transparent banks.