When six members of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) decided to form a trade bloc in 1992, hopes were high that the region was poised to move to the forefront of the global economy and form one of the world’s greatest emerging markets. The global free-trade movement was at its height, and Brunei, Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, Singapore, and Thailand were at the epicenter of a great Asian economic boom. Then came the 1997 financial crisis, which plunged the region into a deep recession. Southeast Asia recovered but was soon overshadowed by the economic upsurge of Asia’s two giants: China and India.

Yet Southeast Asia is back in the sights of global corporations once again. Local companies generated rapid growth in the region during its years out of the global limelight; it is one of the world’s best-kept secrets, as we have maintained since 2012. The combined GDP of ASEAN—which has since grown to ten countries with the addition of Cambodia, Laos, Myanmar, and Vietnam—is projected to nearly double by 2020 as an estimated 120 million people join the

Whether ASEAN will achieve this ambitious target on schedule is uncertain. Even so, rising international trade and investment are steadily binding together the highly diverse economies of Southeast Asia and creating enormous new opportunities for globally minded companies. Our research found that companies both within and outside the region are remarkably bullish about what integration will mean for their businesses and industries, as well as for Southeast Asian economies. In fact, most of them are actively preparing for integration.

To assess how businesses view ASEAN integration, The Boston Consulting Group undertook an extensive study of companies’ sentiments in 2014. We surveyed several hundred top executives of companies of all sizes, based both within and outside the region, and also gauged the opinions of senior government officials. The companies in our study represented a wide range of industries, including energy, consumer products, industrial goods, financial services, and telecommunications. The sample also included a mix of companies with strong footprints across Southeast Asia as well as those with a more moderate or limited regional presence.

The key findings include the following:

- Optimism is high. Roughly 80 percent of the companies we surveyed regard ASEAN integration as an opportunity for their businesses and believe that it will accelerate economic growth in their industries—even though only 25 percent are confident that the region’s governments will continue to push the integration agenda forward. Large, internationally minded Southeast Asian companies and multinationals are particularly bullish.

- Companies intend to expand regionally. Around half the companies we surveyed expect to have a strong presence in at least five Southeast Asian economies within the next five years, compared with one-quarter that have such a presence now.

- Competition is expected to intensify. Eighty percent of companies are bracing for tougher competition in their industries as a result of integration, and around 70 percent predict that this will encourage companies based in Southeast Asia to become more international and more globally competitive.

- Companies are already mobilizing. Whether they regard integration mainly as an opportunity or a threat, the vast majority of companies are taking a range of actions to improve their competitiveness. More than 70 percent are working to increase penetration in their current Southeast Asian markets and to expand across the region. More than half are adjusting their product and services offerings, while around two-thirds are internationalizing their organizations, investing in foreign talent, improving their M&A and joint-venture capabilities, and upgrading their regional supply chains.

- Some countries are gaining competitive advantage. Around 90 percent of companies based in Malaysia and Singapore expect to expand their regional footprints over the next five years. Perhaps not coincidentally, the governments of both nations have also implemented the greatest number of measures to boost the competitiveness of domestic companies. The measures include helping small and midsize enterprises (SMEs) prepare for integration and tightening protection for intellectual property rights.

Yet even with more integration, companies won’t be able to operate across Southeast Asia as seamlessly as they do in, say, Western Europe. Few strong regional institutions link this highly diverse group of nations, which are all at different stages of development and have their own languages, cultures, and political systems. They also face varying business risks.

The winners of ASEAN integration—in terms of both companies and economies—will therefore likely be determined by how successfully the private and public sectors work together now and over the medium term to improve competitiveness. Companies will have to build international, culturally diverse organizations and learn how to tailor their product and services offerings and business models to local conditions. Governments should ensure that their economies are competitive and attractive to foreign enterprises by improving the ease of doing business, investing in talent and innovation, and helping domestic companies—both big and small—prepare for integration.

Companies should not wait until ASEAN governments finish fulfilling their 2015 goals. Southeast Asia has become a region that few global companies can afford to ignore. Through trade and investment, private companies will continue to bind the region together, even without significant new government action. The chief challenge for Southeast Asian companies and multinationals alike is to get into position to capitalize on the growing opportunities.

The Reasons for Optimism About Southeast Asia

The ten nations of ASEAN are on track to create one of the world’s most important economic growth zones. (See The Companies Piloting a Soaring Region: 2012 BCG Southeast Asia Challengers , BCG Focus, March 2012.) Despite recent financial volatility, the combined economic output of ASEAN has more than tripled since 2003, reaching $2.4 trillion by the end of 2013. The Economist Intelligence Unit projects that compound GDP per capita in Indonesia, the region’s most populous economy, will rise 5 percent annually through 2020. GDP per capita growth in Malaysia, Myanmar, the Philippines, Singapore, Thailand, and Vietnam is forecast to range from around 3 percent to 6 percent.

Another decade of sustained growth is expected to give ASEAN even greater weight in the global economy. Though its population is vastly larger than that of Spain, the region’s economy ranked behind Spain’s as the world’s tenth largest in 2003. The economy of ASEAN is now the seventh largest, and by 2020, it is projected to rank fifth, ahead of Germany and just behind India.

Several factors make this growth sustainable. Bold action by governments and the private sector in the wake of the 1997-1998 financial crisis has placed ASEAN on a firm footing. Southeast Asian banking systems are solid. Government debt as a percentage of GDP in the region’s biggest economies is well below the global average. Company and household balance sheets are healthy. The region’s strong productivity growth—which is outpacing that of other rapidly developing economies, such as Brazil, Mexico, and India—indicates that Southeast Asia’s private sector is determined to improve its competitiveness. Such solid fundamentals enabled Southeast Asia’s major economies to bounce back quickly from the volatility that has rocked many emerging markets in the past few years.

Southeast Asia’s growing, relatively young, and increasingly affluent population is a key driver of the region’s growth. From 2013 through 2020, the number of middle-class and affluent individuals in just five ASEAN economies—Indonesia, Myanmar, the Philippines, Thailand, and Vietnam—is projected to surge

(See Asia’s Next Big Opportunity: Indonesia’s Rising Middle-Class and Affluent Consumers , BCG Focus, March 2013.) The region’s working-age population has been expanding quickly, too, and will nearly double—to around 500 million—by 2020. What’s more, research by BCG’s Center for Consumer and Customer Insight has found that Myanmar and Vietnam have the world’s most optimistic consumers: more than 90 percent said that they believe their children will live better than their parents. (See Vietnam and Myanmar: Southeast Asia’s New Growth Frontiers , BCG Focus, December 2013.)

Government efforts to foster trade integration have boosted the region even further. The process began in 1992, when the initial six members of the organization signed the ASEAN Free Trade Area agreement with the goal of eliminating both tariff and nontariff barriers and improving the region’s competitiveness as a global production base. Since then, import tariffs on nearly all goods traded among the original six ASEAN members have been eliminated or reduced to less than 6 percent. (The gains from lowering nontariff barriers are not easily discernible.)

In 2008, Southeast Asian governments pledged to go further and achieve a single market and production base with free movement of goods, services, investment, and skilled labor, as well as a freer flow of capital by 2015 within the ASEAN Economic Community (AEC). The region’s governments have implemented around three-quarters of the legal measures needed to reach these goals, according to the most recent scorecard by the AEC. These include plans for making ASEAN a single market and production base and for improving its economic competitiveness.

Several Southeast Asian governments have been particularly proactive. Malaysia and Singapore lead the region in implementing measures to fulfill the 2015 goals, including all those relating to protecting intellectual property rights and preparing SMEs for integration. SME Corporation Malaysia, for example, encourages enterprises to venture into high-tech and innovation-driven industries and sponsors an annual event showcasing the products and technologies of domestic SMEs. In Singapore, the government agency SPRING has given financial support to more than 1,500 enterprises to help them upgrade their operations, while International Enterprise Singapore helps local SMEs internationalize their businesses. Despite its rather unstable political situation, Thailand has also made impressive progress. To spread awareness of the economic impact of integration, the nation has launched education programs all around the country.

Most Southeast Asian nations have issued ambitious blueprints for improving their competitiveness over the medium and long terms. Singapore, for example, has a comprehensive strategy to establish skills, innovation, and productivity as the basic drivers of economic growth. The Masterplan for Acceleration and Expansion of Indonesia Economic Development 2011-2025 calls for Indonesia to become a developed country by 2025. And Vietnam plans to lay the foundations for a modern, industrialized society by 2020.

ASEAN governments are also making steady progress toward meeting another AEC 2015 goal: to fully integrate the region into the global economy. Several countries are negotiating a comprehensive agreement with the 12-nation Trans-Pacific Partnership, which includes Australia, Chile, Japan, and the U.S. Quite a few Southeast Asian countries have bilateral agreements with trade partners, including China, India, Japan, Nigeria, and Pakistan.

The private sector has responded vigorously to these market-opening moves. Foreign direct investment in ASEAN economies rose 14 percent annually from 2010 through 2012, and trade among ASEAN nations rose by 17 percent per year.

Integration is fostering the rise of regional companies and brands. A group of 50 companies that we have identified as Southeast Asian challengers illustrates the aggressive moves being made by numerous strong players in the region. (See the

Appendix

.) Challengers have at least $500 million in sales, report solid growth in profits and revenues, and have either a strong international presence or ambition. And they operate in all industries—including consumer goods and natural resources—across the region: 12 are based in Malaysia, 11 in Thailand, 10 in Singapore, 9 in Indonesia, 5 in the Philippines, and 3 in Vietnam.

United Overseas Bank, for example, earned 42 percent of its operating profits in East Asian markets outside of its home base of Singapore. It has commercial banking subsidiaries in the region, including in China, Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, and Thailand. The Indonesian packaged-foods company Mayora operates in all ten ASEAN markets as part of its international footprint. Thailand’s Charoen Pokphand Foods has investments in feed mills, farming operations, financial services, and marketing and distribution operations across ASEAN. Malaysia’s Axiata Group has more than 250 million telecom subscribers across Asia.

Much remains to be done before goods, capital, and labor can move freely around the entire region. Nontariff barriers remain significant in some ASEAN countries. While most countries have greatly eased restrictions on foreign equity ownership, liberalization of the financial industry has progressed slowly, according to the Economic Research Institute for ASEAN and East Asia.

The Southeast Asian business environment will remain challenging in other ways. Indonesia, the Philippines, and Vietnam rank poorly in international indexes that measure transparency and corruption, for example. Tensions have flared between Vietnam and China over offshore oil drilling in disputed waters. Political uncertainty and instability remain concerns in some countries.

These challenges should not significantly slow Southeast Asia’s economic progress. And regardless of whether the AEC goals are achieved on schedule, the process of integration has gained momentum of its own, driven by a private sector that recognizes the region’s growing opportunities. Our research shows that even if government progress stalls, companies are confident that the negative impact on growth would be minimal. If the AEC goals are attained, on the other hand, the upside would be significant.

How Companies View Integration

To assess companies’ sentiments toward integration in the ASEAN region, we asked the surveyed executives whether they believe integration will benefit their businesses and the region’s economies—and how it will impact the competitive environment in their industries. We also asked them about their companies’ intentions for regional expansion and whether they are acting to improve their competitiveness to take advantage of integration.

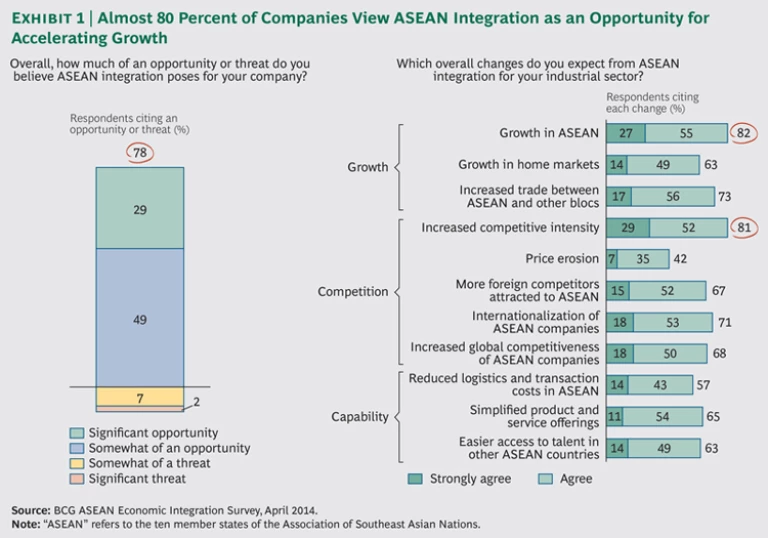

High Optimism. Companies’ attitudes toward integration are overwhelmingly positive with regard to both their businesses and the regional economy. Seventy-eight percent of businesses surveyed said that they view integration as presenting a significant or somewhat significant opportunity. A mere 2 percent said that it poses a significant threat. (See Exhibit 1.)

Companies also believe that integration will provide an economic boost. Eighty-two percent of all businesses surveyed said that they believe it will stimulate overall growth in ASEAN, and 63 percent said that it will stimulate growth in their home markets. Seventy-three percent predicted that integration will boost trade between ASEAN and other economic blocs.

In fact, confidence in the integration process is so high that the majority of companies believe it will continue whether or not the region’s governments are fully supportive. Only 25 percent of respondents agreed with the statement, “Do you think ASEAN governments will continue to actively push ASEAN integration forward, such as through the AEC 2015 goals?” Sixty percent said “maybe,” and 10 percent said “no.” An executive at a major energy company in the region, for example, said that there are still “strong political undercurrents” of protectionist sentiment in Indonesia. An executive at a Malaysian financial company said that “government policies are heavily influenced by strong, indigenous corporate groups” that could slow the opening of markets, and a Vietnamese financial executive said he saw “loosely connected, loosely committed governments” as an obstacle. The degree of optimism, however, varied according to the scale of the companies and where they are based.

Large companies are the most optimistic. Of the companies we surveyed, 88 percent with at least $5 billion in annual sales, and 75 percent with $500 million to $5 billion in sales, responded that they view integration as a significant opportunity or somewhat of an opportunity. That compares with 67 percent of companies with less than $500 million in sales that responded in kind.

An existing presence across ASEAN makes a big difference in companies’ attitudes. Eighty-four percent of companies that identify themselves as regional players said that they view integration as an opportunity. Eighty-two percent of companies operating in two to four Southeast Asian countries also view integration as an opportunity. Of domestically focused companies with a presence in two or fewer Southeast Asian economies outside their home country, 58 percent said that they regard integration as an opportunity, while 22 percent described it as a threat.

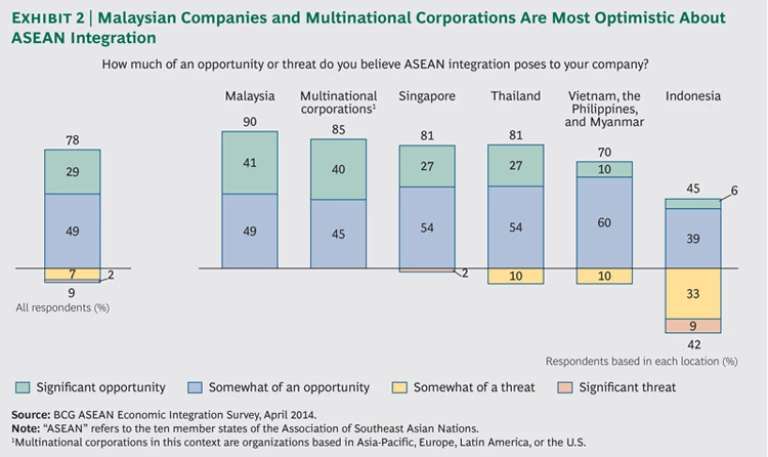

In terms of national origin, Malaysian companies are the most optimistic about integration, with 90 percent indicating that they see business opportunities; they are closely followed by companies in Singapore and Thailand. (See Exhibit 2.) Around 90 percent of companies based in those three nations said that they intend to have a presence in at least two Southeast Asian countries within five years; 33 percent of Malaysian companies, 56 percent of Singaporean companies, and 58 percent of Thai companies said that they intend to establish a regional footprint, with a presence in five to seven Southeast Asian nations within the same time frame.

It is perhaps no coincidence that the governments of Malaysia, Singapore, and Thailand have also been the most proactive in preparing for integration. This suggests that the biggest winners from regional integration could be nations where the private and public sectors are collaborating to seize the opportunities. Indonesian companies indicated the greatest wariness. Although 45 percent of Indonesian executives surveyed described ASEAN integration as an opportunity, almost an equal proportion—42 percent—said that they regard it as a threat. One explanation could be that because Indonesia is Southeast Asia’s biggest market, domestic companies have the most to lose from foreign competition, suggesting that some business leaders perceive that their companies are at a competitive disadvantage with regard to those organizations.

Multinational corporations—particularly those based in the Asia-Pacific region and Europe—are very bullish, with 85 percent expressing optimism.

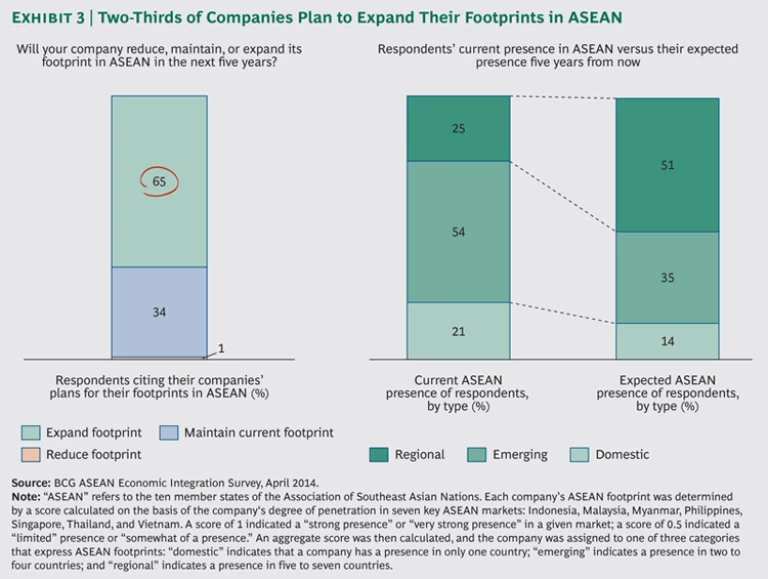

Aspirations for Regional Expansion. A clear majority of companies view integration as an opportunity to grow their businesses. Seventy-six percent of all the companies we surveyed said that they want to increase their market share within the ASEAN region over the next three years; 53 percent said that they had already increased their share during the past three years. Sixty-five percent said that they are currently working to expand their footprints across the region within the next five years. (See Exhibit 3.)

The biggest expansion plans are targeted for the three countries that respondents see as having the most difficult markets within ASEAN: Indonesia, Myanmar, and Vietnam. Roughly 40 to 50 percent of respondents agreed that these three markets are highly or very challenging, citing issues such as protectionism, opaque regulations, histories of political instability, scarce talent, and limited infrastructure. Still, 18 percent of respondents expect their companies to expand in Myanmar, while 19 percent expect to expand in Indonesia and Vietnam. Among the attractions are growing numbers of middle-class and affluent households, stabilizing political and economic environments, and abundant natural resources.

Southeast Asian companies are expected to become far more international as a result. Currently, only 25 percent of companies surveyed said that they are regional, with a strong presence in at least five Southeast Asian economies, while 54 percent identified themselves as emerging regional players, meaning that they have a presence in two to four Southeast Asian countries. Fifty-one percent of companies said that they expect to be regional players in five years, while only 35 percent said that they expect to be emerging regional players. Twenty-one percent of companies said that they operate only in their home markets, but just 14 percent anticipate that that will still be the case in five years.

As should be expected, small Southeast Asian companies have lower ambitions in the region than larger companies, perhaps because of the significant investments required. While around 90 percent of Indonesian companies with sales of more than $5 billion said that they expect to expand within the region, for example, only around half of Indonesian companies with less than $500 million in revenue plan to do so. Similarly, 63 percent of companies that currently describe themselves as domestically focused reported that they plan to retain their domestic focus.

The Impact on Competition. Eighty percent of all the companies we surveyed said they believe that integration will intensify competition in their industries—and 52 percent strongly agreed with that statement. Sixty-seven percent of companies think that integration will attract more companies from outside Southeast Asia.

Companies generally believe that intensifying competition will bring some benefits. Around 70 percent said that it will encourage ASEAN-based companies to become more international and more globally competitive. Only 42 percent said that they expect it will erode prices.

One anticipated benefit of integration is that it will become easier and less costly to conduct business across Southeast Asia. Fifty-eight percent of respondents said that they expect integration to decrease logistics and transaction costs for companies within the region. Sixty-three percent agreed that it will ease access to talent from other ASEAN markets, and 65 percent expect that it will prompt them to simplify their product and services offerings in regional markets.

Perceived Winners and Losers. Whether any given company perceives this heightened competition as an opportunity or a threat depends largely on the company’s current circumstances.

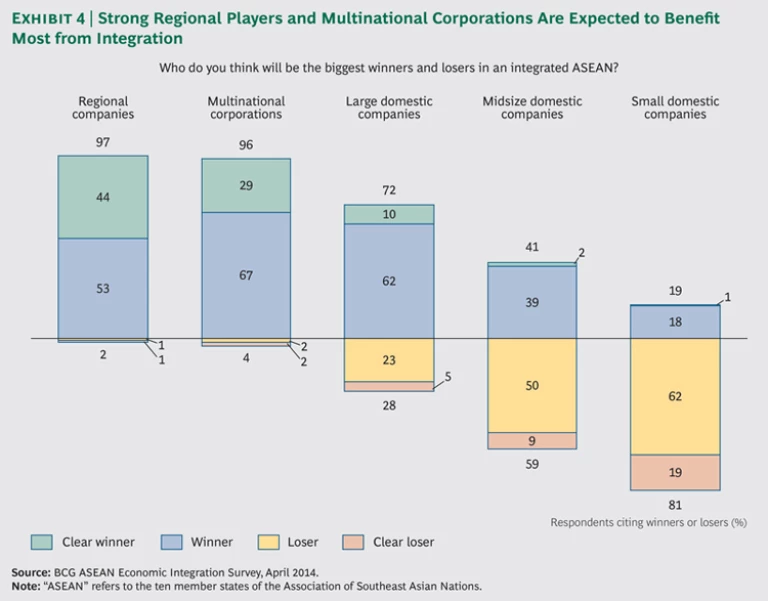

Overwhelmingly, respondents said that they expect multinationals and regional players—such as the 50 BCG Southeast Asian challengers—to reap the greatest gains from ASEAN integration. SMEs that focus primarily on their home markets have the most to lose. (See Exhibit 4.)

Ninety-seven percent of all the companies we surveyed said that they believe regional players will be winners; of these respondents, 44 percent said that such companies will be clear winners. Twenty-nine percent of all companies surveyed expect multinationals to be clear winners. Such corporations have the international scale, organizational capabilities, operational excellence, and regional reputations needed to recruit and retain talent. Large domestic companies are also expected to win from ASEAN integration, according to 72 percent of respondents.

Domestically focused SMEs are viewed as most vulnerable to greater foreign competition. Eighty-one percent of respondents said that they expect small companies to lose out in ASEAN integration; 19 percent branded them as clear losers. Fifty-nine percent predicted that midsize domestic companies will lose out.

ASEAN integration certainly provides ample opportunities for smaller companies, but those businesses are less likely than larger ones to invest in areas that will make them more regionally competitive—such as market research, international talent, and programs to build operational excellence in manufacturing and supply chain management. Financial, and especially managerial, resources are the most critical constraints.

Preparing for Integration

Companies across Southeast Asia are mobilizing to take advantage of the big opportunities opened by integration. The vast majority of companies surveyed reported that they are taking action to prepare their organizations. Globally minded regional companies and multinationals are doing so most aggressively. We asked companies about how they are going to gain access to markets, improve their organizations’ capabilities, recruit talent, and upgrade operations.

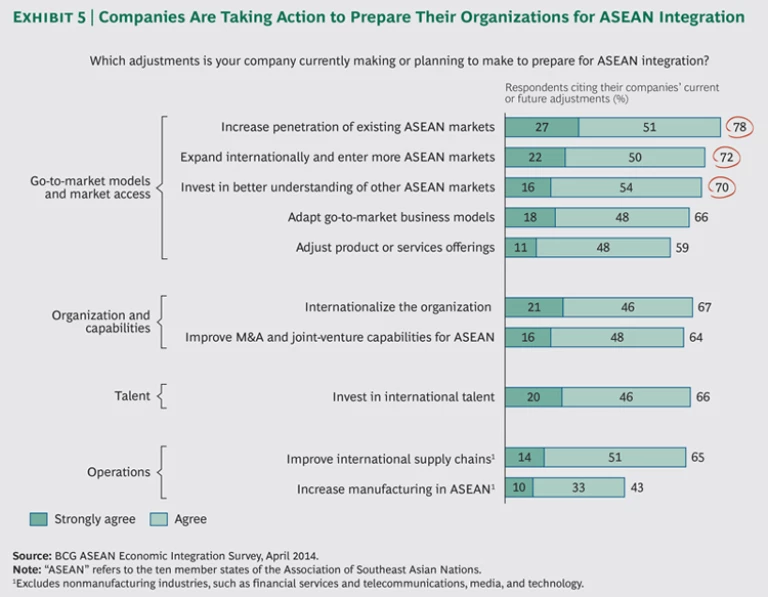

Seventy-eight percent of all companies said that they are making adjustments to better penetrate the Southeast Asian markets in which they currently operate, while 72 percent said that they are working to expand both within the region and internationally. (See Exhibit 5.) Seventy percent are also investing to better understand other Southeast Asian markets, while 66 percent are adapting their go-to-market business models to local conditions and 59 percent are adjusting their product offerings and services.

The highest priorities in terms of organizational capabilities are to internationalize (67 percent) and to improve M&A and joint-venture capabilities (64 percent). Sixty-six percent said that they are investing in international talent. In terms of operations, 65 percent reported that they are improving their global supply chains, and 43 percent are increasing their manufacturing capacity within Southeast Asia.

The priorities of the companies vary considerably depending on their size and country of origin. Large companies are preparing for ASEAN integration more actively than smaller ones. Eighty-four percent of companies with more than $5 billion in revenue are acting to increase penetration in the Southeast Asian markets where they already have a presence. Investing in international talent and improving their international supply chains are other top priorities.

Our survey also revealed that multinationals and regional companies based in Southeast Asia are concentrating on different things to boost their competitiveness. Multinationals are focusing on understanding the nuances of specific Southeast Asian markets more clearly and on adapting their business models to local conditions. By contrast, big globally minded companies based in Southeast Asia—which have a stronger understanding of local markets and can readily apply strategies honed in other rapidly developing economies—are placing greater emphasis on building international organizational capabilities and operational excellence. (See the sidebar, “How Two Southeast Asian Companies Are Going Regional.”)

HOW TWO SOUTHEAST ASIAN COMPANIES ARE GOING REGIONAL

Few companies are in a better position to capitalize on ASEAN integration than the area’s strongest regional players. Many of these fast-growing, internationally minded companies have been methodically building their presence in the region for years. Now they are moving to seize strategic advantage. Jebsen & Jessen and Universal Robina illustrate two paths for becoming regional.

Jebsen & Jessen, a diversified conglomerate based in Singapore, has been expanding its engineering, manufacturing, and distribution businesses across the region for five decades. It established its first operations in Malaysia in 1963 and expanded to Thailand and Indonesia in the 1970s. Now it has operations in nine ASEAN economies, and it recently opened a representative office in the tenth—Laos.

The company taps into the technological expertise of its international partners and the local know-how and talent of its many partners in Southeast Asia. The company’s joint venture with Terex’s heavy-equipment manufacturer Demag, for example, has eight production facilities and 35 service centers across the region. Today, half of Jebsen & Jessen’s businesses—including specialty chemicals, cranes, hoists, rail projects, and offshore cables—have market- leading positions in Southeast Asia.

Universal Robina, the Philippines’ leading consumer-foods company, has been increasing its market share in six of the ten ASEAN countries by adapting its business models and broad range of products to local consumers’ tastes. In 2006, Universal Robina began making and selling its C2 line of flavored teas in Vietnam—the only market outside the Philippines where it does so—after the company’s research indicated that the drinks would become big hits there. Ads remind consumers that the tea is grown in a famed Vietnamese tea-growing region.

In May 2014, Universal Robina announced that it would establish a facility in Myanmar—a new market—to make biscuits and confectionaries that appeal to local consumers. The company’s sales have grown by an average of 13 percent annually since 2008.

It may be a while before Southeast Asia fully enjoys the free flow of goods, capital, and labor that the ASEAN Economic Community hopes to reach in 2015. But the experiences of Jebsen & Jessen and Universal Robina show that farsighted companies are reaping the rewards of integration now.

Most of the measures outlined above are actions that forward-looking companies are taking regardless of whether ASEAN governments significantly advance the regional-integration agenda much further.

Taking Integration to the Next Level

The economic integration of Southeast Asia is an ambitious vision that presents important opportunities both for companies based in the region and for multinationals. But at this point, companies should not be waiting for ASEAN governments to take further action. Southeast Asian integration has gained momentum of its own. The race for competitive advantage across the region is well under way. If those governments implement the remaining measures needed to achieve the free flow of goods, capital, and labor, that race will accelerate.

Securing talent is the most urgent need for all companies targeting the challenging ASEAN markets. Indonesia, for example, faces growing gaps in its workforce, from entry-level workers and middle managers to senior executives. (See Tackling Indonesia’s Talent Challenges , BCG Focus, May 2013.) A scarcity of talent can become a hindrance to understanding local markets and to successful sourcing, distribution, product development, and marketing. Nurturing and retaining talent, therefore, will become a critical source of competitive advantage.

Beyond that, regionally minded Southeast Asian companies and multinationals generally face different sets of priorities. Regional companies should focus on making their organizations international and attaining operational excellence so that they can compete head-to-head with the best in the world. Multinationals, however, must strive to deepen their knowledge of a wide variety of local markets and adapt their products, business models, and organizations accordingly.

Southeast Asian companies that currently have a domestic focus have three choices. They can choose to stay domestic and channel their energies into defending or increasing their market shares. They can go regional by branching out into neighboring economies and working aggressively to gain share organically or through M&A. Or they can create partnerships and extend their reach through joint ventures and alliances with multinationals and regional challengers that want to expand at home.

The approach a domestically focused company chooses should depend on its industry and its position in the market. In the consumer goods and industrial sectors, defending domestic markets may prove difficult. In regulated industries, such as financial services and telecommunications, a domestic orientation may remain viable. Domestic conglomerates that are in multiple businesses need to decide in which industries they should attempt to go regional.

ASEAN governments can help domestic businesses meet these challenges and make ASEAN economies more attractive in ways that go beyond trade and financial-market liberalization. Governments can expand the pool of local talent by investing more in higher education and vocational training. They can also reduce risks and improve the ease of doing business, such as by continuing to fight corruption and by making regulations more transparent and predictable. Governments can upgrade infrastructure through direct investments or public-private partnerships.

Governments must also help domestic SMEs, which have the most to lose from integration and are generally doing the least to prepare for it. For political reasons, countries may be tempted to raise nontariff barriers in the name of protecting such enterprises. But that would be shortsighted: in the long run, open markets provide the best conditions for companies to innovate and become more productive. They also provide citizens with better choices of goods and services. Governments could choose instead to fund programs that improve companies’ understanding of other regional markets, facilitate joint ventures with new entrants, increase productivity, and provide better access to talent through closer partnerships between SMEs and educational institutions.

Southeast Asian companies should also keep working with their governments to advance the AEC agenda—or at least to preserve the gains that have been achieved so far. Support by business is critical for building the political will necessary to further reduce nontariff barriers and to avoid protectionist impulses. Halting or reversing the process of integration would likely damage economies far more than it would help. Consumers with the strongest spending power, facilitated by cheaper regional travel and easier online shopping, will gravitate toward markets that provide the best value for their money. Protected companies in closed markets would have the most to lose in that scenario.

While we hope that governments will not become more protectionist, we also do not expect many additional major breakthroughs. Governments have already created tremendous opportunities. It is up to the private sector to seize them.

Acknowledgments

This report would not have been possible without the efforts of our BCG colleagues Pim Altena, Chong Chi Hung, and Yong Hui Yoong.