In 1869, two great enterprises, the Central Pacific Railroad and Union Pacific Railroad, joined tracks at Promontory, Utah, marking completion of the U.S. transcontinental line. This concluded a grand contest: the Central Pacific racing eastward from Sacramento and the Union Pacific rushing westward from Omaha. Judged by mileage, the Union Pacific won, having laid 1,085 miles of track compared with Central Pacific’s 690. Yet many consider the Central Pacific stretch the greater feat. Blasting, grading, and tunneling through the Sierra Nevada, the Central Pacific faced taller odds than the Union Pacific met on its route across the Nebraska flatlands. Central Pacific’s reward reflected these odds. The U.S. government paid $16,000 per mile for track on level ground and $48,000 per mile for track uphill.

The rewards for the transcontinental railroad were based on miles of track. For businesses today, the contest is framed in terms of shareholder value. And a key driver of shareholder value is growth. Over a typical one-year time frame, upper-quartile value creators of the S&P 500, for example, create twice as much value from growth as from margin or cash flow improvement. Over the longer term, growth for these outperformers drives 75 percent of shareholder value creation. These observations resonate with many of our client CEOs who have driven operating improvement to points of diminishing return. They—and their investors—know that continued value creation depends on top-line growth.

Yet growth is a challenge. Most of our clients lack the tailwinds that help propel a Facebook or an Amazon. Rather, they must “grow uphill,” facing maturity and commoditization (which erode advantage) or disruption and changing customer behaviors (which erase it). Stagnant developed-market demand, costly M&A, lottery-like innovation odds, and increasing price transparency stand in the path of growth. This is what growth looks like for “the rest of us.” And yet there are players that, like the Central Pacific, beat the odds and reap disproportionate rewards.

Uphill Growers

In search of uphill growers, The Boston Consulting Group studied the performance of 1,600 global companies with revenues over $1 billion. Our study’s design focused on mature businesses that found ways to grow sustainably—growth for the rest of us. To take a longer view of value creation and to avoid extremes in the market cycle, we looked at rolling five- and ten-year periods covering 1990 through 2007. Our criteria: stagnant revenues for the five prior years, breakout growth at double the rate of peers, and sustained growth for at least five years. Only 310 companies—1 in 5—made the cut. And among these uphill growers, there were companies that destroyed value in their attempt—through bad acquisitions, expansion of a doomed core, or unrewarded innovation. We focused on value-creating, uphill growers and looked for patterns among their moves.

Porsche is emblematic. By 1993, Porsche had posted six years of declining revenues. Historically, the company had emphasized a craftsmanship culture and perpetuation of a sports performance niche. It had rejected expansive adjacencies, with one executive asserting that “an entry-level Porsche is a used Porsche.” Meanwhile, foreign competitors were bringing performance to a wider audience at a better price. Volumes sank, and bankruptcy rumors arose. In 1992, a new CEO, Wendelin Wiedeking, declared his ambition. He saw Porsche as “a bigger fish in a bigger pond.” His moves are instructive, and so is their order. First, he cut production layers, reduced the build time of a Porsche from 120 hours to 45, and struck assembly partnerships on low-cost lines. This earned Porsche the “right to grow,” creating necessary competitiveness and investment funds. Next, he reinvested in the neglected 911: twin turbochargers for power and suspension refinements for handling. This strengthened a financially crucial model and the brand overall.

This done, Wiedeking embarked on systematic adjacent expansion. The Boxster brought performance to a new income segment and created a new demand funnel for the brand. Next, the Cayenne broke the performance compromise in the SUV segment. The successful four-door Panamera followed. Work then began on an electric hybrid that would deliver 0-to-60 miles-per-hour acceleration in 2.3 seconds and 78 miles per gallon. At Porsche, Wiedeking toppled statues: a Porsche built on a line with Volkswagens; a Porsche badge on a family hauler. But across these choices, he shrewdly preserved one thing: under each hood, an engine designed and built in Zuffenhausen, Germany. Performance would remain the essence of the brand—a differentiating ticket to adjacent growth. Wiedeking’s strategy reignited Porsche’s growth, quintupling volume from 1992 through 2002. And as each extension brought incremental volume and accretive profit, an average of 19 percent annual total shareholder return was created.

Starting Position Matters

The Porsche experience is illustrative but not universal. Not every company can profitably employ Porsche’s strategy of adjacent expansion. Pursued adjacencies—be they markets, price points, channels, or categories—can fail and also carry the risk of distracting from priorities in the core. Indeed, companies such as Starbucks and WD-40 have restarted growth by avoiding adjacent distractions, seeking to “do one thing well,” and pursuing this approach to its limit. If similar strategies yield dissimilar results, how are executives to choose among the many paths to growth?

Should we grow the core or expand adjacently? Should we build growth organically or acquire it? Should we pursue one investment path doggedly or place multiple bets? The truisms often quoted in response to these questions—typically, M&A destroys value; growth is best pursued within the core—crumble when applied specifically.

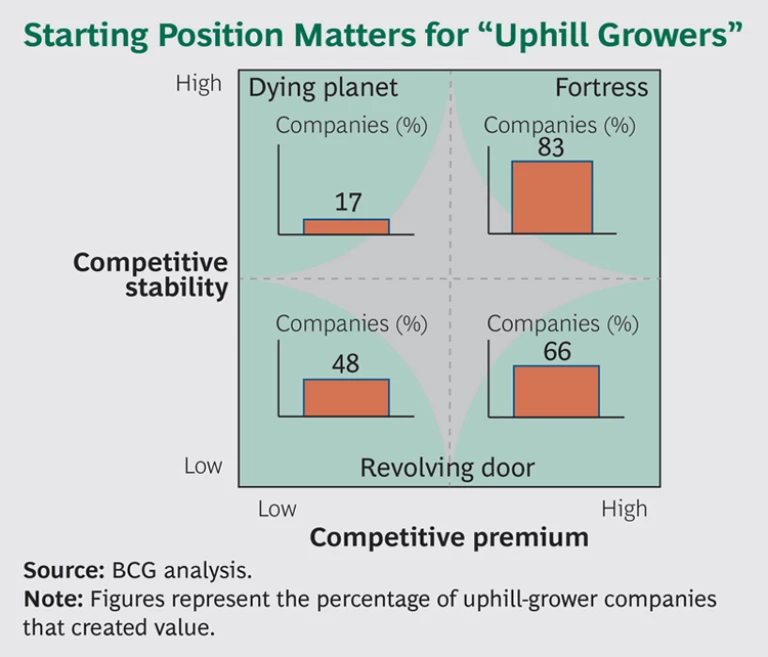

Our uphill-grower research suggests useful direction. Among the most important is that starting position matters. We define starting position along two dimensions. The first is competitive premium: Does the business command a gross-margin advantage over rivals? There are many ways to accomplish this. Wal-Mart achieves its premium through a low-cost supply chain; Target, through differentiated marketing; and Kroger, through excellence in store operations. Other companies rely on powerful brand equities, control points in the business system, or scale. The second dimension is competitive stability: Is the business characterized by equilibrium (relatively steady market shares, stable demand, or high entry barriers) or turbulence (competitive churn, disruptive technologies, or fast-changing consumer behavior)? A business’s stance in relation to these two questions has bearing both on the probability that a dollar invested in growth will create value and on which growth paths to pursue. (See the exhibit below.)

In the top-right quadrant of the exhibit, “fortress” businesses command a competitive premium in a stable game. Of these companies, 83 percent created value through their growth investments. Their advantage is insulated by entry barriers, relationships, and “sticky” customers. The downside of this stability is stability. Volume is hard to lose—and hard to gain. Value-creating growers with this profile typically reinvest some growth capital to reinforce their core premium, and they project that advantage into close-to-home adjacencies. They look just beyond a stable core to exploit their advantage. Porsche, an example of a fortress player (once it had reinforced its premium), created value through adjacency. P&G, another example, used cash generated from its advantaged detergents business to fund disruptive adjacent expansion in household-cleaning (Swiffer) and air-freshening (Febreze) products.

At the top left, “dying planet” businesses are disadvantaged players in a stable game. Only 17 percent of these players saw a value return on their growth investment. Sector stability makes positional change difficult, and growth investment becomes good money after bad. The 17 percent that defied these odds typically reshaped their portfolios and pursued a more distant adjacency. General Dynamics, a subscale defense player, shed 70 percent of its portfolio, bought Gulfstream Aerospace, and shifted from hardware to IT. Over a five-year period, the company quadrupled the top line and created shareholder value at triple the rate of the S&P 500 index. More often, the value-creating course for dying-planet players is to attack their premium disadvantage first—moving to the top right—before taking their 17 percent chances on growth.

At the bottom of the exhibit, where the game is turbulent, competitive premium matters less. The odds of valuable growth approach 50-50 in both quadrants. This is intuitive: turbulence implies that today’s advantage may be tomorrow’s liability. The fluidity and churn of a turbulent sector offer growth opportunities to winners and losers alike. Value-creating growers in both turbulent quadrants pursue similar strategies. Rather than pursue a single, long-range growth bet, successful growers place a “bet portfolio” across core, adjacent, and more distant frontiers. Experiments are rapidly killed or scaled as results unfold. In these “revolving door” businesses, success comes not from the power to predict but from the agility to respond.

Consistent Lessons

Four lessons from our uphill growers apply across every quadrant.

Earn the right to grow. Value creators pursue growth in its proper order: operational soundness first, followed by core premium reinforcement and core or adjacent expansion. Nearly all value-creating growers in our study held or expanded margins as they grew. They avoided expensive resuscitation of structurally unwinnable positions or divested these altogether to concentrate on areas of advantage and strong capital returns. They built margin through concurrent, aggressive fund-the-future operational improvement. And they pursued profitable growth by favoring adjacent segments with higher margin exposures.

Know your advantage. Companies do best when they define precisely what they do well and use that knowledge to edit portfolios and evaluate growth opportunities. Wolverine, one of our uphill growers, had an advantaged capability in making sanded pigskin leather. This allowed the company to make shoes people have to wear feel like shoes they want to wear. Understanding this advantage helped Wolverine make choices, divesting losing positions in retailing and in athletic shoes and aggressively expanding in casual and work shoe adjacencies.

Aggreko, a U.K.-based provider of power generation and temperature control solutions, overcame growth headwinds by exploiting its advantage in rapid temporary power deployment. As volume stagnated in its core business, providing power for construction projects and events, it found a strong tailwind in addressing electricity blackouts and shortages in developing markets.

Expand your field of vision. Companies have biases and comfort zones related to where and how to grow that can constrain opportunity. Look broadly before selecting a growth plan. Are there faint signals in the core—such as unusually profitable customers or rapidly growing subcategories—that can be amplified? Beyond the core, consider adjacencies that deliver standalone growth, profit accretion, or some reinforcing benefit to the core. Finally, new frontiers of opportunity can exploit old advantages or assets in radically new ways. Gerber Products, for example, has grown by multiple means throughout its history. It expanded organically from baby food to the toddler segment. And it found an unconventional way to exploit its trusted brand by moving adjacently into juvenile life insurance.

Integrate vision, choices, and action. Having envisioned the phonograph, Thomas Edison drew a quick sketch, marked it with the words “Make this,” and handed it to his machinist, John Kruesi. The unheralded Kruesi turned vision into action, a translation that eludes many value-destroying growers. One of our clients—who says that vision is “where the rubber meets the sky”—is taking pains to translate the company vision into concrete choices on where to play and invest. The company is creating a culture of growth execution by chartering specific initiatives, defining new and needed capabilities, and aligning operating metrics and targets. This alignment of vision, choices, initiatives, capabilities, and metrics is a hallmark of our successful clients—and of valuable growers.

Our research shows that when companies face tough odds, even small changes in the trajectory of profitable growth can create substantial value. Over longer time frames, mature companies that increased their top-line growth even modestly (by 2 points or more) delivered shareholder returns 40 percent higher than the market average. They even handily beat the returns of historically fast growers that simply sustained their rate of growth. This offers encouragement for the rest of us. And lessons from value-creating growers provide the playbook, which can help business leaders tilt the odds as they blast, grade, and tunnel their way to growth—uphill.