What do microprocessors, power tools, and air transportation have in common? On the face of it, not much. But dig a little deeper and you’ll find that each of these industries has followed a similar pattern over the past 20 years. Each has a large number of established companies. Each has seen an accelerating pace of product innovation . And each industry has also, unfortunately, seen a decelerating pace of growth.

In response, leading companies in these industries have moved beyond product innovation and redefined the basis of competition. Companies such as ARM Holdings, Hilti, and Qantas have combined new products with new pricing strategies, partnerships, cost models, and a multitude of other changes to their businesses. They have achieved impressive results, and they are not alone.

This is business model innovation (BMI) : a powerful but underleveraged tool that can drive breakout growth in a company’s core business.

Improving Core Growth

Core growth is a critical driver of performance. Even as industry boundaries blur and the shift to emerging markets increases, most companies—around 60 percent in our sample—still derive a majority of their revenues from their core markets and businesses.

Achieving core growth, however, is challenging. Over the past five years, the average growth rate in core businesses and regions was less than half that of noncore ones. This should come as no surprise. As core markets become saturated and new competitors emerge, traditional approaches that have successfully driven growth for years—product innovation and pricing strategy, for example—are reaching the point of diminishing returns.

For leaders of companies facing this reality, now may be the time to move beyond traditional strategies and explore new solutions, just as ARM, Hilti, and Qantas have done. Starting on this journey raises a number of important questions:

- Are there signs that traditional levers that worked in the past are now falling short?

- What alternative solutions can drive superior performance?

- How can leaders successfully implement these solutions?

When Traditional Levers Fall Short: Three Pitfalls

Companies have historically relied on a handful of tried-and-true tools to drive organic growth within the core. Three of the most common are product enhancements, new-product introductions, and pricing strategies such as discounts and promotions. While these levers should still play important roles in a company’s overall growth tool kit, they may not be enough to stimulate strong core growth. Most large companies have operated in the same core business for years—or even decades—and these levers inevitably hit a point of diminishing returns. As customer needs change and new competitors emerge, incremental approaches may not be enough to sustain a growth trajectory.

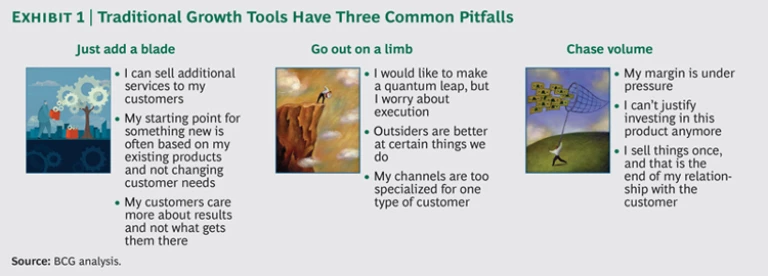

Companies facing these challenges tend to act in similar ways. We have synthesized these into the following three pitfalls, each of which corresponds to a traditional growth lever. (See Exhibit 1.)

- Just add a blade. Incremental product enhancements—such as improving a razor by adding another blade—stop producing results when customers derive most of the value from a service, experience, or outcome related to the product and not just from the product itself. When this is the case, companies that focus on a product-based value proposition will limit their own potential, make innovation investments that are not valued by customers, and risk becoming obsolete because the true customer need lies outside what the product can provide. Until very recently, pharmaceutical companies faced this challenge after developing better drugs that targeted only a small portion of the overall treatment pathway without addressing broader health and wellness needs.

- Go out on a limb. When companies make innovative changes to a product or service without adjusting its supporting partnerships, capabilities, and distribution channels, the results can be disappointing. Even breakthrough innovations—with fundamentally different customer-value propositions—often fail if they aren’t accompanied by the right operating model. An extreme example is LA Gear, a shoe brand that was popular in the 1980s and 1990s. The company changed its value proposition from “fashion” to “performance” to enter the men’s basketball shoe market, but it failed to enhance its suppliers’ manufacturing capabilities accordingly. The shoes literally fell apart on national TV.

- Chase volume. Many companies are tempted to reduce prices or find other creative discounting approaches in the hope of driving increased sales volumes. However, price reductions alone—without corresponding changes to other elements of the business model—can quickly lead to significant margin erosion. Premium offerings, traditional revenue models, and a high cost structure can all limit companies’ ability to reduce prices profitably. Retailers frequently suffer from this pitfall when they discount products heavily; they see an initial increase in store traffic, but ultimately margins plummet.

How can companies pursue the same objectives of traditional growth levers—enhancing customer value, developing a fundamentally new value proposition, and lowering the price point—but avoid the associated pitfalls?

The answer for many has been to move beyond these traditional tools and consider innovation across the entire business model. To be sure, BMI is less familiar than traditional growth levers are and can be perceived as riskier. But as the examples below illustrate, the returns more than outweigh the risks.

The BMI Opportunity: Same Goal, Different Results

The key advantage of BMI over traditional growth levers is that it affords businesses greater degrees of freedom. It can create more value because an orchestrated set of changes across the value proposition and business model can create a new basis of advantage that is harder for rivals to match.

The traditional tools, including product innovation and pricing strategy, typically involve changes to one, or perhaps two, dimensions of a business. With a new product, the manufacturing process may change; with a price discount, there may be a new way to communicate with the customer. By contrast, BMI involves changes to a much broader set of dimensions. We have broken these down into six key business-model elements. Three define the value proposition: product or service offering, target segment, and revenue model. Three define the operating model: value chain, organization, and cost model.

The ability to change multiple elements simultaneously—and in a coordinated manner—is what allows BMI to do the work of traditional growth levers but avoid the pitfalls.

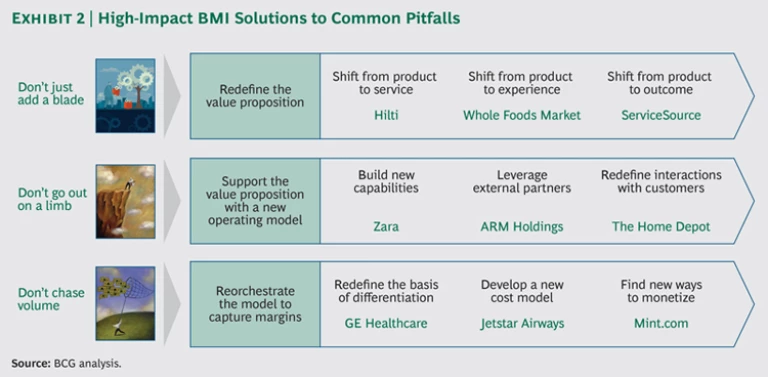

Consider the chasing-volume pitfall. Rather than just reducing the price, companies could also redefine their offering (such as a simplified product with cheaper materials), build a new cost model (such as greater automation and outsourcing), or fundamentally change the revenue model (such as a shift from one-time purchases to smaller, ongoing fees). Or they could do some combination of all three. By using this essence of BMI, we have developed nine particularly high-impact BMI solutions for avoiding typical growth-strategy pitfalls. (See Exhibit 2.) These solutions, and the examples we provide to illustrate them, can lead to a fundamentally new business model.

Don’t Just Add a Blade—Redefine the Value Proposition

When product innovation is leading to diminishing returns—when new blades no longer offer the profit lift they used to—customer needs are not necessarily completely satisfied. What is more likely is that unmet needs cannot be addressed simply by improving products. Think about compact discs. The fact that creating a thinner, lighter CD added little value did not mean that customer music needs were completely satisfied; it meant that needs had to be satisfied with entirely new offerings: digital music and accompanying devices.

If customer value goes beyond the reach of traditional products and services, it may be time to redefine the value proposition in order to recognize that the product is not the main source of customer value. Start by considering the following questions:

- What pain points result when a customer uses the product?

- What else besides the product has an impact on customer experience?

- What objective is the customer trying to achieve by using the product?

Answers to the questions above often reveal a new value proposition, frequently one that shifts from a product to a service, an experience, or an outcome.

Shift from Product to Service. Sometimes customers don’t value the product as much as they value getting the job done. For example, competition in the construction tools industry has typically been based on product features and innovation. Contractors purchase tools out of necessity but care more about completing jobs and moving on to the next project. These customers have several pain points that have not been addressed by traditional product-based value propositions. Tools are expensive and require significant up-front capital. Tool inventories have to be managed regularly to ensure that the tools are not stolen and that they remain in proper working order. There is no efficient way to share tools because employees often move from one job to another. And finally, contractors are forced to buy several particularly expensive tools that are necessary but used only in rare situations.

Hilti, whose core business is tool manufacturing, picked up on these unaddressed pain points. In response, it shifted from selling tools to selling a tool management service aimed at alleviating the burden on contractors so they could focus on getting the job done. Hilti now leases tools to contractors, guarantees availability of the right tool at the right time, and automatically upgrades customer fleets with the latest equipment. It also provides theft insurance. Its service is accompanied by a new revenue and operating model. Many contractors, who in the past had purchased a small share of their tools from each competitor, dramatically increased their share of business with Hilti in order to obtain the full benefits of the company’s tool-management service.

Hilti’s success depended on possessing a deep understanding of how the customer uses tools and what causes them frustration. Based on this understanding, the company expanded its view of the role it could play in delivering value to customers. This was a shift from a purely product-based mind-set to one that also included supporting services and solutions.

Shift from Product to Experience. Sometimes customers are looking for an emotional connection and not just a product. Whole Foods Market, for example, has found an innovative way to differentiate itself in the highly competitive grocery-store sector, providing customers not just with groceries but with a unique shopping experience. Whole Foods Market has leveraged high-quality natural and organic products, strong customer service, and attention to corporate social responsibility to give shoppers the experience of a healthier lifestyle.

First, the company’s decentralized structure gives store managers significant autonomy to discover local sources for products, ensuring that high-quality goods meet unique needs of customers in each store location. Second, Whole Foods Market has made an effort to inspire its employees through a common set of values, leading to effective customer service in an industry traditionally known for employee indifference. Within each store, employees are trained to be knowledgeable and friendly, helping customers select the best items to meet their needs. Third and finally, staying true to the third tenet of its mission statement, “Whole Foods—Whole People—Whole Planet,” the chain engages in “green initiatives,” such as reducing its own environmental footprint and giving 5 percent of profits to community and nonprofit organizations each year. Customers can gain the experience of living a healthy, responsible lifestyle when shopping at Whole Foods Market—both by buying healthy products and supporting a company that contributes to sustainable practices. In this way, the company delivers customers the whole package, allowing it to charge premium prices.

The Whole Foods Market business model has driven breakthrough growth and high margins in a traditionally low-margin industry. From 2007 to 2012, Whole Foods Market achieved a 12 percent compound annual growth rate (CAGR) in revenue growth, a 17 percent CAGR in EBITDA, and it averaged around 8 percent EBITDA margins. Its strong performance has put it on a level above traditional industry leaders such as Kroger, for which revenue and EBITDA grew at 7 percent and 4 percent, respectively, with an average EBITDA margin of 5 percent.

There are many opportunities for companies to shift from products to integrated customer experiences through BMI. Nike+ lets athletes and users track their performance statistics and improvement over time and track their individual goals along the way. As Nike CEO Mark Parker has said, “[Nike+ is] about much more than a shoe. It represents a shift for Nike from product to product plus experiences.” Similarly, Apple, with its iTunes and iPhone offerings, combined innovative products with a wide range of music, videos, and games and other apps. The key is to recognize what enhances a customer’s experience when using the product and then directly incorporate these services into the offering.

Shift from Product to Outcome. Sometimes addressing an unmet need is not enough. Consider the example of ServiceSource. The company, involved in cloud-based software, recognized a potentially huge, frequently neglected source of revenue for many companies: recurring revenue streams from contracts and subscription renewals. In the technology sector alone, ServiceSource estimates that around $30 billion in renewal revenue is not captured annually; around 50 percent of customers do not renew simply because of a lack of contact from a sales team. ServiceSource saw an opportunity to help clients capture this revenue but realized that companies might be wary of the offering because they would be putting significant revenues at risk by outsourcing a portion of their sales process. To overcome this, ServiceSource had to develop an innovative business model to effectively launch its unique offering and capitalize on this unmet customer need.

When ServiceSource started, it offered an outsourced managed-services solution, using its clients’ customer data to identify renewal opportunities. ServiceSource differentiated itself when it entered this market by not just selling a service but instead selling an outcome. The company charges customers on the basis of renewal revenues generated, not the hours of sales service provided. By using this pay-for-performance revenue model, ServiceSource shares the risk with its clients by putting its own revenues at risk.

ServiceSource’s business model goes beyond just an innovative pricing model. As Christine Eckert, executive vice president of marketing, strategy, people, and systems for ServiceSource, said recently, “We offer clients a set of managed services, where we can solve the problem for them. We can give them everything they need to outsource this problem to us. We take it on and deliver them back a result.”

Many companies intuitively understand the outcomes their customers are trying to achieve, but changing the value proposition to selling this outcome directly—instead of simply selling products and services—requires an innovative business model. To transition away from a more traditional model, companies need to make the following changes to their revenue models:

- A shift from product sales to outcome-based payments

- An expansion of offerings that includes complementary products and services

- An operating model adapted to support the new approach to selling, including new sales tactics, incentives, and value-chain configurations

Don’t Go Out on a Limb—Support the Value Proposition with a New Operating Model

When an organization has had a series of failed innovations, the problem may not be with the innovations themselves. The real issue may be that the company has gone out on a limb and introduced the innovations without the operating elements required to support them. Established companies are often tempted to apply the same capabilities, channels, and value-chain configurations to new innovations. Changing the operating model—along with the value proposition—is an imperative because it creates the appropriate support system to enable breakthrough value creation.

In many ways, the operating model is the foundation—the roots—of the business, and it needs to reinforce the new insight that is driving the entire business-model redesign. Without the right root system, new limbs are at risk of withering. The operating model can change in many ways, but shifts tend to involve building new capabilities, leveraging external partners, and redefining interactions with customers.

Build new capabilities. In Zara’s case, this meant building a lightning-fast supply chain. Zara’s branded stores and trendy apparel are ubiquitous throughout Europe and are rapidly growing in new markets. The retailer pioneered the short-cycle business model in fashion, with a compelling value proposition for consumers: thousands of designs per year, constantly refreshed based on changing customer tastes. This value proposition would not be possible, however, without Zara’s unique supply-chain configuration and corresponding set of capabilities.

While most apparel retailers outsource manufacturing and logistics, Zara retains the majority of its value chain in-house, including even seemingly mundane activities such as cutting. At the same time, the firm has built a rapid store-to-manufacturing feedback loop, requiring sophisticated logistics as well as close interaction between store staff and designers. These capabilities allow the company to achieve best-in-class lead times: less than a month from design to store shelves, compared with lead times of up to nine months for competitors. Because of this unique model, Zara has enjoyed consistent growth, averaging more than 15 percent over the past decade.

Zara’s success points to a key lesson for companies: it pays to set an ambitious vision for a new value proposition and break any compromises that stand in the way of achieving it. This type of agenda typically requires a new operating model—with a new set of capabilities. Companies can build these capabilities internally or, as the next example illustrates, make use of external partners.

Leverage external partners. In the case of chip-maker ARM Holdings, doing better meant doing less. A recent study tallied nearly 4,000 distinct Android models available to customers—and this is just a portion of the overall smartphone market. Phone manufacturers are all competing to deliver maximum performance and battery life in the smallest possible form. Doing so, however, requires customization of microprocessors to fit the dimensions and performance requirements of each unique model, which is a tough task for just one company.

ARM recognized this Herculean task and decided to create a chip-licensing business and not a chip-manufacturing business. It sells what is essentially the blueprint to the “brain” of a chip to a network of 250 semiconductor partners, which then design customized and integrated “systems on a chip” to support a variety of different mobile devices. By doing less itself and enabling customization from this wide network, ARM has built a model that supports smaller and more energy-efficient chips compared with its competitors’ more standardized—and power-hungry—offerings. ARM’s licensing business created a platform for collaboration with more than 1,000 partner companies, including hardware, software, and design vendors. It helped the organization gain more than 95 percent market share in mobile devices.

External partners can bring many different assets and capabilities to the table. In the case of ARM, the key was its partners’ thorough understanding and technical know-how, which allowed the company to customize and improve ARM’s blueprint. Regardless of the specific assets and capabilities external partners bring, leveraging those assets requires new ways of operating and delivering value. Companies must reconfigure their value chains, incorporate new elements into their offerings, and think carefully about which capabilities would benefit more from external partners than through an in-house effort.

Redefine interactions with customers. For The Home Depot, growth required focusing on how to sell as much as on what to sell. The retailer drove many years of strong growth with its innovative do-it-yourself concept—helping consumers do home improvement projects that once necessitated a contractor. The company provided the necessary materials and taught consumers how to get the job done. However, in the wake of the housing crisis, far fewer people were doing renovations. The market for home improvement products and services shrank significantly. The Home Depot recognized that improving its customer-engagement model was critical to capturing a greater share of the remaining demand and driving growth. As Marvin Ellison, head of U.S. stores, said at the company’s 2012 Investor and Analyst Conference, “We sell projects, not just products…. The project nature of our business places an increased level of importance on the engagement between our customers and associates.” The Home Depot deployed a three-pronged approach to address the distinct needs of consumers and professional customers and increase associate productivity:

- It redesigned the sales associate role with a new customer-centric focus.

- It leveraged technology to further enhance the shopping experience.

- It sought to forge deeper emotional connections with customers beyond the in-store experience.

The Home Depot retrained all its associates in 2008 and again in 2010 to revive commitment to customer service. The Customer FIRST (“find, inquire, respect, solve, thank”) and FIRST for Pro training programs were geared toward making sure that associates understood the distinct needs of consumers and professional customers. In addition, The Home Depot instituted its 60/40 program: a reduction in sales associates’ noncustomer-facing activities through operational improvements and an increase in time spent on customer-facing activities to 60 percent from 40 percent.

Four technology-driven innovations have further improved customer experience: the FIRST phone, The Home Depot iPhone apps, payments through PayPal wallet, and the customer care resolution team. The FIRST phone, a cross between a phone and a walkie-talkie, can be used to raise alerts to store managers and other associates, to check out customers (especially helpful when there are long lines), and to locate products within the store or at nearby stores in real time. To further improve shopping convenience, separate iPhone apps were designed for consumers and professional customers with features such as a “view it in your home” tool for consumers and a materials calculator for professional customers. Products can be purchased through the app and then picked up in the store. To increase speed and convenience at checkout, a recent partnership with PayPal allows customers to check out using PayPal wallet, a mobile payments solution. Finally, in an effort to drive continuous improvement, the customer care resolution team identifies dissatisfied customers by scanning social-media sources for complaints and reaching out to solve their issues, as well as by providing feedback to management about how to improve customer service processes.

Going beyond in-store service, The Home Depot engages with the local community with weekend clinics and “do-it-herself” workshops to form a deeper emotional bond with customers. For professional customers, The Home Depot has a special delivery program to bring materials directly to the job site.

By engaging with customers on a new level, The Home Depot has significantly increased its score on the American Customer Satisfaction Index, boosting it by 11 points from 2007 to 2011. This has helped drive revenue growth (4 percent) and EBITDA growth (11 percent) past Lowe’s, its main competitor, from 2009 to 2012.

The Home Depot’s story highlights the fact that often the most important element of the operating model is not how the product or service is made but rather how it is experienced by the customer. In today’s market environment, companies must step into their customers’ shoes to understand that the way a product is delivered can have as great an impact as the product itself.

Don’t Chase Volume—Reorchestrate the Business Model to Capture Margins

When company leaders decide that prices need to decrease, a complex problem arises. It is a common strategy to reduce prices and try to make up for lower margins with increased volume, but chasing volume is also a dangerous choice: companies risk significant declines in profitability if the increased volume fails to materialize.

Organizations that succeed in reaching this new price point while maintaining—or even increasing—margins embrace the complexity and recognize that it is a delicate task that requires changing not just the price but several elements in the business model. Reaching a lower price point might involve a new offering, operating model, revenue model—or a combination of all three. BMI can enable profitable value creation by reorchestrating the business model elements around the new price point. This often involves redefining the basis of differentiation, developing a new cost model, and finding new ways to monetize a low-cost (or even free) offering.

Redefine the basis of differentiation. For GE Healthcare, redefining the basis of differentiation meant creating a unique offering at a low price point. In the 1990s, the company served the Chinese ultrasound market with sophisticated machines that had primarily been developed for hospital imaging centers in the U.S. and Japan. GE soon found out that the $100,000-plus devices were too expensive for the vast majority of its customers in China—rural hospitals and clinics—and they were not portable enough to be brought to the patients that were typically unable to travel to an urban hospital. GE responded by developing a compact, portable ultrasound machine that combined a regular laptop with sophisticated software—and sold at nearly one-fifth the price of the full-scale versions. Although the imaging quality was not as high, the compact machine served the rural clinics sufficiently well; doctors used it for applications such as spotting stomach irregularities and enlarged livers and gallbladders. The company has seen dramatic growth of these machines not only in China but also in other developed markets around the world.

There are many ways for companies to redefine how an offering is differentiated to support a lower price point. Swatch repositioned its traditional watches as low-priced fashion accessories with plastic bands and flashy designs, while Redbox shifted from selection to convenience by offering a limited range of new-release movies in kiosks. The key is to understand the different sources of customer value and pick one that, while still enhancing that value, can be delivered more cheaply.

Develop a new cost model. As airline Qantas faced the challenge created by low-cost carriers (LCCs), it realized that making incremental changes in cost structure would be insufficient. It needed to launch its own LCC with competitively superior economics. Many incumbent airlines had tried to introduce LCCs, but virtually all failed—leaving companies such as Southwest and JetBlue to dominate this space. For many LCCs of established airlines, connection to the parent and its traditional cost model hampered efforts to reduce costs, despite changes such as greater seat density and more limited on-board offerings.

In 2004, Qantas introduced its LCC, Jetstar Airways, with an entirely new cost and operating model. It features a single and separate plane type in its domestic operation, point-to-point flights, separate commercial systems, and a heavy mix of online-generated sales. Jetstar also has autonomy from Qantas on most business functions.

Qantas recognized the importance of creating a new model that was not burdened by old ways of operating. Many companies may be tempted to adjust their existing cost models when faced with fierce competition. But when the business model is challenged by truly disruptive change, what is often required is an entirely new approach.

Jetstar has been an enormous success, expanding its domestic operations to include long-haul international business flights and establishing a number of short-haul franchise businesses in Asia (Singapore, Japan, and Vietnam). Annual revenues now exceed $3 billion, and Jetstar earns higher margins than does its more premium-focused parent airline.

Find new ways to monetize. Mint.com , an online personal-finance service offering from software company Intuit, creates value for multiple customers—but extracts it only from some. Mint helps users, as the company says, to “simplify the business of life” by offering a free service that allows them to track cash, checking and savings accounts, credit card transactions, investments, and loans all through a single-user interface. Mint gives users a clear and complete picture of all their finances in one place. With Mint, there is no local software to install, and it is a service that can be accessed through any Web browser or mobile device. This allows for quick and easy access to finances on the go. Mint makes money from this free service by offering targeted recommendations for ways to save on credit cards, home loans, insurance, and other services. Mint also gets paid a commission when users switch their accounts to a new bank. Mint not only offers a value for individuals but it also uses information about individuals to create value for financial institutions.

Be Prepared for Resistance

Armed with these solutions, companies should find it easier to navigate around the common pitfalls that stand in the way of core growth. Understanding the solutions, however, is only the beginning of a longer journey. To drive meaningful impact, these ideas must take root within the organization, receive sufficient funding, and be given the runway needed to achieve scale.

BMI can take years to fully show results. It entails greater risks as well as longer-term payback than more incremental moves, and there is often organizational resistance to change. Indeed, implementation challenges are the largest obstacle many companies face when innovating their business models. The following are a handful of best practices to help companies manage resistance:

- Have the CEO set a bold ambition for growth from the outset. It may seem counterintuitive, but it often works best if he or she provides few details on how to achieve the target. The gap between current state and aspiration can be a powerful motivator for change.

- Bring in experts who have successfully implemented new business models in the past. Shy away from those in nearby sectors; the key is to find people with fundamentally different perspectives.

- Secure alignment up front—before the innovation effort even begins—to ensure a sufficient runway for the new model to succeed. This often requires engagement at the highest levels, including the board.

- Ensure that the working team includes both champions and naysayers. And engage with the latter early and often to address concerns well before the go-no-go decision.

- Commit to a small scale up front. It is important to succeed somewhere first before implementing the new business model more broadly.

- Finally, plan for managing the new model as a separate business or division. A new organization, with separate talent, processes, and metrics, is often required to bring the new capabilities that are needed to run the business.

Starting the Journey

With solutions and best practices in mind, company leaders should reflect on their three- to five-year plan for the core business. For some, it might make sense to stow away the BMI tool for the time being. But for the 50 to 70 percent of companies with large but slow-growing cores, now is likely the time to consider using this tool. For those about to begin the journey, there are four important questions that leaders should take to their organization:

- What is the growth ambition for the core business?

- Are traditional approaches still sufficient, and will they remain so?

- What business model solutions from outside the industry could deliver superior return on investment?

- How could these solutions be put to work in the organization?

Bolder BMI solutions can be the key to driving growth in the core business and maintaining sustained outperformance. Along the way, leaders must watch their business cycle, their competitors, their customers, and especially those pitfalls.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the following: Sachpreet Chandhoke, Shriram Salem, and Nicolas Finger for their help in writing the piece.