Over the next few years, European policy makers will tighten regulations governing insurance distribution. Three regulatory initiatives—the Insurance Mediation Directive (IMD2), Packaged Retail and Insurance-based Insurance Products (PRIIPs), and the Markets in Financial Instruments Directive (MiFID2)—will change how insurance is sold and how insurance products are structured. Although no one knows what the final rules will be or how they will be implemented, the European Parliament’s recent agreement on proposals has removed a lot of uncertainty. It is clear the changes will be sweeping in scope.

Insurers, therefore, cannot afford to do nothing. With top-down analysis suggesting that some market participants face potential volume declines as large as 25 percent, insurance companies must rethink their current strategies and turn this threat into an opportunity. They can do so only if they form a picture of the new regulatory environment—even while some details are still coming into focus.

In broad strokes, the intentions of European policy makers have been clear for months. They want to accomplish the following:

- To minimize intermediaries’ conflicts of interest by illuminating incentives and affiliation—namely, whether they are beholden to a particular insurer or insurers—and reducing or even banning commissions that could be deemed inappropriate

- To enhance the industry’s professionalism by raising the standards for sales advice, documentation, and qualifications of salespeople

- To empower the customer by adding transparency about products and intermediaries’ remuneration

- To level the playing field for financial institutions across Europe by harmonizing the rules

In our view, the optimal way to proceed is to build a scenario that takes into account what the regulatory authorities—the European Commission and Parliament—have proposed so far and that uses these proposals to define a realistic worst case as a base scenario. This realistic worst case boils down to five likely changes, which can serve as the basis for some initial but crucial decisions. (To get a broad sense of what is under consideration, see Appendix 1.)

New Regulations: A Realistic Worst-Case Scenario

The first likely change would be to extend and raise advisory standards. Among other things, this means that before an insurance product can be sold to a customer, the intermediary must do a detailed “customer fit” analysis—similar to what banks and asset managers have to go through to sell complex investment products. It will also involve more extensive documentation.

The second change is hard disclosure of the intermediary’s individual remuneration and the total cost loadings of an insurance product, accompanied by additional “comprehension alerts” that highlight the complexity of life insurance. In the past, the amount of money an intermediary made as a result of selling a particular product had been invisible to the customer. In the next regulatory era, that may well change. If a customer knows that an intermediary is getting a €1,000 commission for selling a particular product, for instance, that knowledge may alter the dynamics of the relationship.

The third change will be a dramatic increase in the sanctions and personal liabilities for misconduct or failure to comply with insurance rules. These sanctions would affect not just intermediaries but also the insurance companies themselves and the managers who run them.

The fourth change involves raising the minimum qualifications of intermediaries by requiring them to regularly take more formal exams with stricter requirements. (The impact of this change may be small in countries where standardized qualification requirements are already in place.)

The fifth change would involve a ban on product “tying.” In the future, although product bundling will still be allowed, companies will likely have to make the components of every bundle available for individual purchase—and they may be forbidden from tying the sale of one product to the sale of another. (For example, companies that make loans are now allowed to require that customers also buy an insurance product, guaranteeing their payments. Such tying may be prohibited in the future.)

The Possibility of Commission Bans

Of course, in a climate that is still uncertain, it makes sense to be prepared not just for a realistic worst case but for the worst case you can imagine. For European insurers, such a scenario would include banning commissions for independent advisors—an idea that was originally put forward by the EU commission and that is still being debated across Europe. We have excluded this from our realistic worst case, partly because the idea was dropped in the most recent proposals and partly because we think there will be ways of circumventing such a policy. (The most obvious way to avoid it would be for intermediaries to change their status from independent to being tied to multiple companies.)

A more intrusive worst case could involve a prohibition on commissions of every type, regardless of product or channel. That would render many of today’s sales models unsustainable, especially those of agents who are tied to a specific company.

It is important for insurers to develop an understanding of how banning commissions might affect their businesses in the long term. They can do this by studying the impact that commission bans have had in the UK, the Netherlands, and Scandinavia—regions that have already introduced such bans and that have put into effect other rules beyond what pan-European regulators are currently contemplating. (See Appendix 2.)

Existing Trends Will Gain Momentum

To whatever degree and in whatever order the base-case changes come, they will accelerate four trends that are starting to emerge in the European insurance industry: declining productivity, diverging transactional and advisory businesses, increasing competition from asset management products, and rising prominence of direct-sales channels. In fact, all countries with more advanced regulation—the UK and the Netherlands, in particular—are already dealing with these trends.

Declining Productivity. One consequence of the new regulations will be a decline in individual sales-agent productivity—especially in the more strictly regulated life-insurance business. Productivity will go down because intermediaries will need to devote more of their time to expanded advisory and documentation requirements. Hardest hit will be those sales agents who currently focus on quick sales and don’t do a lot of individualized analysis before recommending life insurance products to customers. These salespeople may have to entirely revamp their approach. Those who already use holistic advisory tools—which incorporate data about customers’ individual financial situations and expectations—won’t be hit as hard. But even those sales agents will face the challenge of additional documentation and increased liability.

Another contributor to declining productivity will be a drop in the number of customers willing to buy from an intermediary. This is inevitable as remuneration becomes more transparent and some agents find themselves unable to convince customers that the level of their commissions or fees is justified. This will be a particularly big problem in life insurance, prompting some customers to opt for lower-cost options—such as direct channels and asset management products—or to stop buying insurance altogether.

The productivity decline will put so much pressure on some agents’ income that they won’t be able to make a living and will have to leave the business. This will affect mostly agents whose productivity is already low.

Diverging Transactional and Advisory Businesses. The increased costs and liability risks of providing advice—as a result of new requirements for documentation and suitability analyses—will become a disincentive in the low-value—that is, low-income—part of the market. With fewer intermediaries working the low end, the mass market will need to be turned into a “pull” market—one in which customers buy insurance without anyone selling it to them individually. But not every mass-market customer will do this; some will simply drift away, causing volumes in this part of the market to fall.

The higher-value segment of the market, comprising wealthier customers, will become the more logical focus of advisory services. But in an era of greater transparency, intermediaries offering advice in this part of the market—whether their income is fee based or commission based—will have to demonstrate their value very clearly and offer products that cater to the specific needs of their affluent customers.

AN UNINTENDED SIDE EFFECT OF REGULATION

While regulation may well succeed in protecting consumers from harmful insurance-sales practices, it is also likely to have one financial consequence that hasn’t yet received much attention: a negative impact on retirement savings.

As a result of the Insurance Mediation Directive (IMD2) and Packaged Retail and Insurance-based Insurance Products (PRIIPs), the life insurance market in most European countries will probably undergo a significant decline—in some cases exceeding 10 percent, even without any restriction on commissions.

Although a portion of those sales will be diverted to asset management products, not all will be—and the result will probably be a rise in immediate consumption and a drop in retirement savings (if no regulatory countermeasures are taken). Since this behavior is likeliest among people who have the lowest level of retirement savings to begin with, it is something that policy makers may eventually find themselves having to address.

The net effect of these different dynamics will be to create an “advice gap” at the low end of the market. Even though this trend is probably unavoidable, insurance companies and their distributors will likely take steps to hold on to their customers in both segments. At the high end, they will focus more on specific, high-quality, and flexible propositions. At the low end, there will be more standardized products supported by online “self advice” engines and remote sales support, so customers will feel confident about making a largely unassisted direct purchase. Insurers will have to revamp their product portfolios accordingly. (The low end of the market may see another shift that few people have considered. See “An Unintended Side Effect of Regulation.”)

Increasing Competition from Asset Management Products. Compared with banks and asset managers, life insurers have benefited from a less stringent regulatory environment over the past few years. The lower liability risks and less stringent documentation requirements have made it more advantageous to sell life insurance products than other investment products. However, this has not prevented banks and asset managers from trying to take a share of the retirement savings business from insurers. And as new regulations level the playing field for asset managers and insurers, banks and asset managers will intensify their efforts to muscle in on this part of insurers’ business.

This trend will be enhanced by the introduction of so-called key-information documents, which are basically financial spec sheets. There seems to be a high likelihood that these documents will end up being the same for life insurance and asset management products. However, since key-information documents will probably focus on expected returns over one-, five-, and ten-year periods—the periods most relevant to asset management products—life insurance products (which are not typically tailored toward short-term returns) may be put at a disadvantage.

Rising Prominence of Direct-Sales Channels. The net effect of all of these changes will be to increase the importance of direct-sales channels—specifically, online distribution, telephone or remote-video fulfillment centers, and in-person service at insurance company branches. At the same time, platforms will gain importance. Intermediaries will increasingly use B2B platforms to simplify their business and bring costs down; consumers will use B2C platforms to find advice and buy products online.

The Market Impact: Varying Top-Line Effects Across Countries

To gain insight into the impact of regulations, The Boston Consulting Group and financial-research company Sanford C. Bernstein conducted an economic analysis of how certain European markets would be affected if the realistic worst-case scenario materializes.

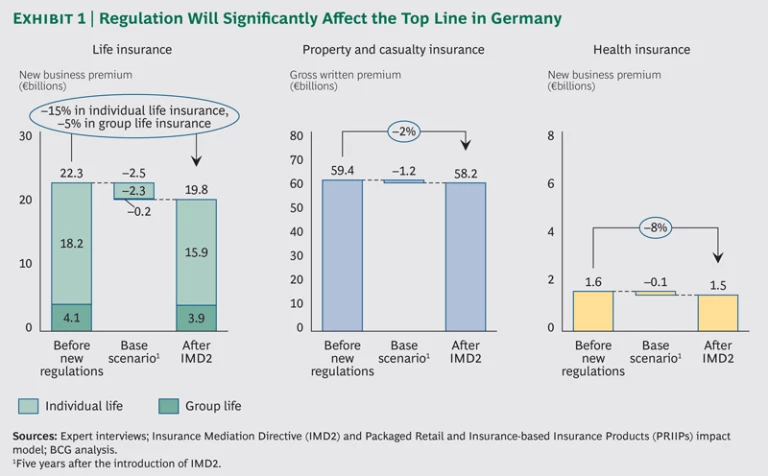

In Germany, for example, markets for life and health insurance would probably decline by about 15 percent and 8 percent, respectively. (See Exhibit 1.) The market for property and casualty insurance—a less complex area that is not the focus of the new regulation—would remain largely unchanged. (This analysis reflects only pan-European regulatory change; it ignores other factors that could have an impact on Germany’s insurance market, such as more stringent national regulations, interest rate changes, and changes in consumer behavior.)

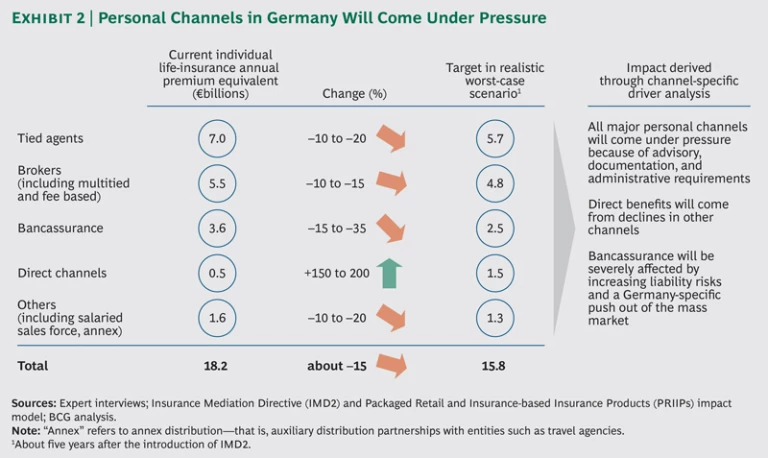

Our analysis suggests that the sales channels in Germany would be affected in different ways. (See Exhibit 2.)

- Tied agents would suffer a decline in productivity—although the impact would vary. Agent networks that aren’t fully dependent on life insurance or are already providing sophisticated holistic advice would fare better than average; agent networks focused on aggressively selling standard life-insurance products would fare worse.

- Brokers, or independent advisors, would be affected by the same dynamics as their tied peers. But they would fare slightly better, because brokers already leverage holistic and automated advisory tools to a greater extent than tied agents do today.

- Bancassurance would see a less severe decline in productivity, but this channel would still lose significant market share. There are two reasons for this: First, many German banks already operate at low levels of profitability, and the introduction of new regulations would cause the mass-market insurance products they sell to become even less profitable for them. Second, at the high end of the market, banks will increasingly try to sell their own asset-management products instead of newly regulated insurance products.

- Direct channels would gain substantially from the small base they have today. But this gain would not all go to the websites of direct insurers. Existing insurers that are able to combine self-service direct models with additional forms of assistance—such as advice by phone or integration with salaried sales forces—would also benefit from this growth.

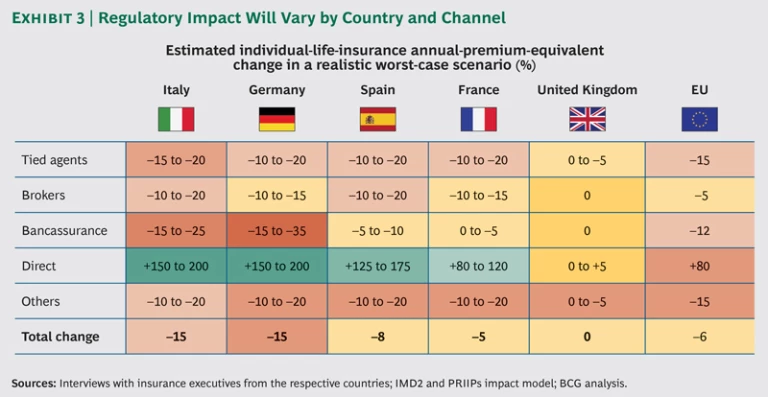

We did a detailed analysis of four other countries—Italy, Spain, France, and the UK. (See Exhibit 3.) For those countries and Germany, we expect an overall revenue decline of about 6 percent in individual life insurance. On the face of it, this may not appear too dramatic. But the decline in volume will vary significantly among countries and sales channels—and even more dramatically among individual market participants.

Here is a summary of how the realistic worst case would play out in those four countries:

- Italy. Overall impact would be similar to that in Germany, with some differences in channels. In particular, the Italian bancassurance channel, which is extremely important—making up about half of the Italian life-insurance market, compared with 20 percent in Germany—would probably hold up slightly better than it would in Germany. But we expect a slightly bigger impact on Italian tied agents (16 percent market share) and brokers (29 percent market share), since these sales channels would have further to go in terms of complying with new rules and offering high-quality advice.

- Spain. The impact on Spanish agents and brokers is expected to be very similar to that of Germany. However, we predict that the Spanish bancassurance channel—which has approximately an 80 percent share of the life insurance business—to hold up relatively well in the medium term. Because banks in Spain need to simplify their balance sheets, they are going to be less enthusiastic about selling their own asset-management products. In addition, Spanish retail-banking networks still suffer from significant overcapacity. This will make it easier for them than for German or Italian banks to handle increased documentation and advisory requirements—at least until this overcapacity has been reduced (which may happen after the implementation of IMD2 and PRIIPs).

- France. French brokers (who have a 12 percent market-channel share) and tied agents (7 percent market share) will be affected by the same dynamics and to a similar extent as their German counterparts. But the bancassurance channel—which makes up about 60 percent of the French individual-life-insurance market—will fare much better in France. This is because, when it comes to selling life insurance, French banks are already largely out of the mass market. Moreover, the revenues and profits these banks earn by selling life insurance to affluent customers is simply too significant for them to give up. The long and the short of it is that asset management products don’t currently have the same replacement potential in France that they have in other markets. For this reason, the top-line threat to insurers is less severe and probably farther off in France than it is elsewhere.

- UK. British insurers have already had to adapt to national regulations that have moved faster and been more severe than those taking shape at a pan-European level. As a result, the EU regulations will likely have minimal impact on most companies in the UK—for the same reason that tossing a bucket of water on someone who has just emerged from a swim in the ocean doesn’t have much impact. The only channel in the UK that is likely to be affected in a negative way is the already-decimated broker channel, which may thin out some more because of increased documentation requirements. Any loss in volume here, however, will likely be made up by more business in the direct channel.

These country-by-country forecasts give a sense of how life insurance is likely to change as a result of regulation. Individual company performance, of course, will fall into a considerably wider range. For instance, life insurance companies with a large footprint in Germany and Italy would be very vulnerable; companies in countries that have stronger starting positions in direct transactions would probably benefit. Our analysis of real-life market participants in these five countries suggests that the revenue impact would vary from a decline of as much as 25 percent for some companies to an increase of as much as 9 percent for others.

Critical Success Factors

What will distinguish the winners in the new regulatory environment? We believe that they will exhibit six critical success factors, which will also be important to investors.

- Diversified Business Portfolios. Because the new regulations will mostly target life insurance, there is an obvious risk in being too dependent on this area. Companies that can leverage other insurance products through their sales forces—health and property and casualty in addition to life—will be better off.

- A Strong Presence in Direct Channels. The first must-have here is a lineup of life insurance products that people can buy without assistance—perhaps because of an easy-to-use online interface that connects to sophisticated advice algorithms. But only a small percentage of people will feel comfortable making unassisted purchases of life insurance. Successful direct offerings will also include remote support through call centers; “cobrowsing,” during which support personnel temporarily take control of a customer’s computer in order to help the customer find an important online form or complete a transaction; and retail locations where the customer can speak to a service representative.

- Best-in-Class Advisory Systems and Support. Systems and processes that automate the sales and advice function (including call centers that handle some of the advisors’ administrative work) will allow agents to focus on lead generation and selling—countering the impact of new regulations. Besides saving advisors’ time, well-designed systems may also reduce liability risks for the sales staff and for the insurer itself.

- Cost Efficiency. A low cost basis will be crucial in an era of increased regulation. It will help at the low end of the market, where there will be less advice and less product differentiation—and, therefore, thinner margins. And it will help at the high end to the extent that it gives intermediaries lower-priced, more competitive products to sell.

- A Product Line Customized to Channels and Customer Segments. If ever there was a time when the same insurance product could be sold to all customer segments in all channels, that time is over. In the future, insurers will need to offer simple products at competitive prices for mass-market customers who opt for self-service, as well as a variety of products responding to the specific needs of their wealthier customers and fitting the specific requirements of their revised advisory processes.

- Strong Brand and High Customer Satisfaction. As pull sales gain importance, lead generation will become a significant challenge. To address it, insurers will need strong brands and superior customer satisfaction. Closely regulated Scandinavia offers an example; the fastest-growing insurers in that region all leverage word-of-mouth that is marketing based on high customer-satisfaction ratings.

No-Regrets Moves That Insurers Can Make—Now

With traditional distribution channels weakening, insurers can’t afford to wait until every aspect of the new regulatory environment has come into focus. The changes that will be necessary require time to implement—and to put off making them is to risk losing access to the market. Instead, insurers should start making adjustments that will be beneficial regardless of the exact shape of the industry after IMD2. Among these no-regrets moves, four are vital:

- Make strategic investments in the direct and digital parts of your business. Insurers must look for ways to excel in direct sales. Part of this involves having an intuitive Web interface with simple-enough product offerings, and part of it involves providing support where intermediaries and customers need it. Opposition from traditional channels will make this an organizational, as well as a tactical, challenge.

- Shore up your position in bancassurance. Regulation poses a huge threat to insurers’ bancassurance businesses, since banks, like insurers, will face higher liability and sales costs. Given how important the banking channel is for many insurers, they should make an across-the-board effort to improve their bancassurance products as well as the service and support they provide to their banking partners. Once lost, a preferred banking-partner position will be hard to recover.

- Look for new ways to support your agents. It will be essential to get the most out of advisors who serve the lucrative higher end of the market and have the wealthiest customers. Having best-in-class advisory systems is a big part of the answer. The idea is to put advisors in a position to have more customers and, thus, do as well as before—even if they earn less money per sale after new regulations take effect.

- Support and develop platforms for brokers. As cost effectiveness and regulatory compliance become bigger challenges, brokers will continue to consolidate and will seek to further automate the administrative sides of their sales processes. Providing brokers with the right technical platforms to do so can be a great opportunity for insurance companies. Success can ensure their long-term presence in this part of the market and even deepen their relationship with brokers. In contrast, insurers that fail to support or provide broker platforms might find themselves losing a large part of their sales margin to third-party platform providers.

Turning a Threat into an Opportunity

Sales regulations will accelerate and deepen some of the most momentous trends in the insurance industry. It will change the competitive dynamics of all European markets and separate market participants into clear winners and losers.

The silver lining is that regulation is much more than a technical challenge for compliance departments and an exercise in minimizing the downside of change. The new regulations present a significant opportunity to gain market share. The insurers that prepare well and take some smart early steps to evolve will be in the best position to capitalize on this coming opportunity.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Robert Hertzberg for writing assistance.