Business leaders today are faced with an extremely dynamic business environment, characterized by technological innovation, blurring boundaries among industries, shifts in customer behavior, scarcity of talent, and huge variations in growth across regions. HR functions need to help companies meet these challenges as true strategic partners. To fulfill this mandate, however, HR leaders need a clear view of their current capabilities, their priorities over the next three to five years, and the best way to tailor efforts to improve.

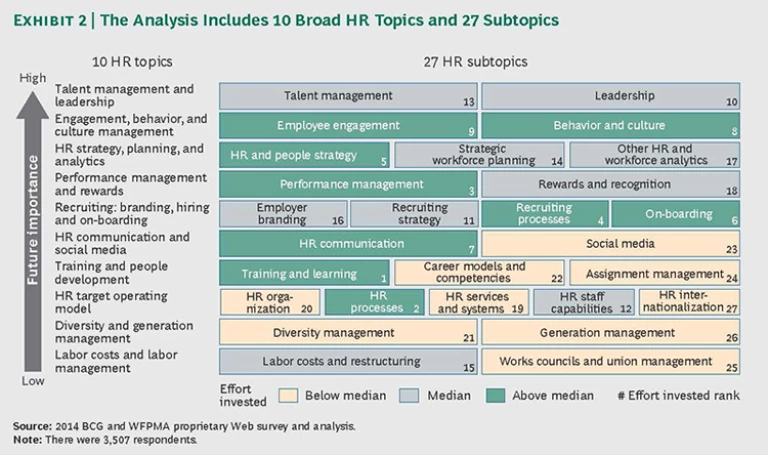

This report, the eighth in The Boston Consulting Group’s Creating People Advantage series, explores key trends in people management by considering ten broad HR topics and 27 subtopics. We looked at each subtopic’s future importance, companies’ current capabilities with regard to the subtopics, the levels of effort invested in them, and how urgently each subtopic needed action. We also explored the link between people management capabilities and economic performance.

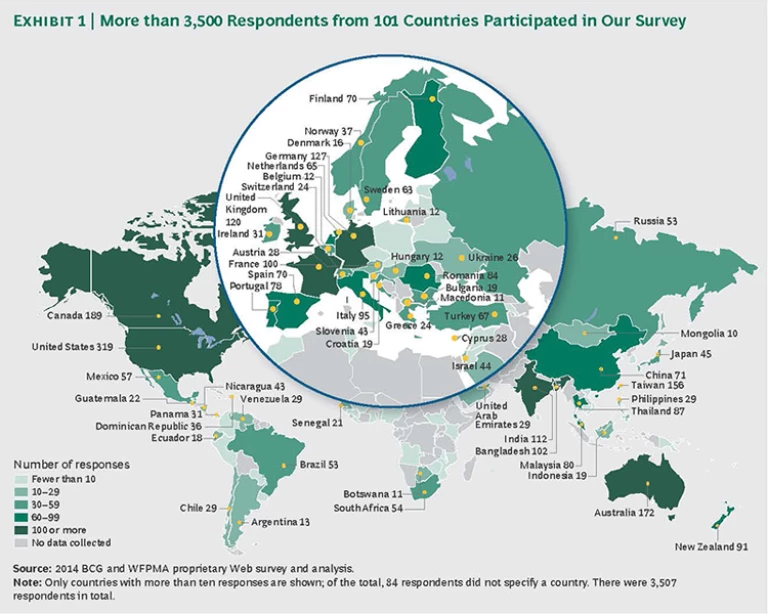

In this year’s survey, 3,507 respondents from 101 countries participated, representing industries including industrial goods, consumer goods, and the public sector. In addition, we interviewed 64 HR and non-HR executives at leading companies around the world. The following are among the most compelling findings:

- HR capabilities correlate with economic performance. Companies that have strong capabilities in HR topics—such as talent and leadership; engagement, behavior, and culture management; and HR strategy, planning, and analytics—show significantly better financial performance than companies that are weaker in those areas.

- Analytics and key performance indicators (KPIs) give HR a seat at the table. There is a strong correlation between the use of KPIs and the strategic role of HR. HR leaders who want a role in strategic discussions with the business must be able to quantify workforce performance. This goes beyond “input” metrics, such as cost and head count, toward more sophisticated “output” indicators, such as productivity.

- KPIs should link to strategic actions. Even high-performing organizations, which are generally more data driven, do not use their KPIs systematically to formulate strategic actions. A clear prioritization and selection of KPIs and tools is needed to achieve best-in-class results.

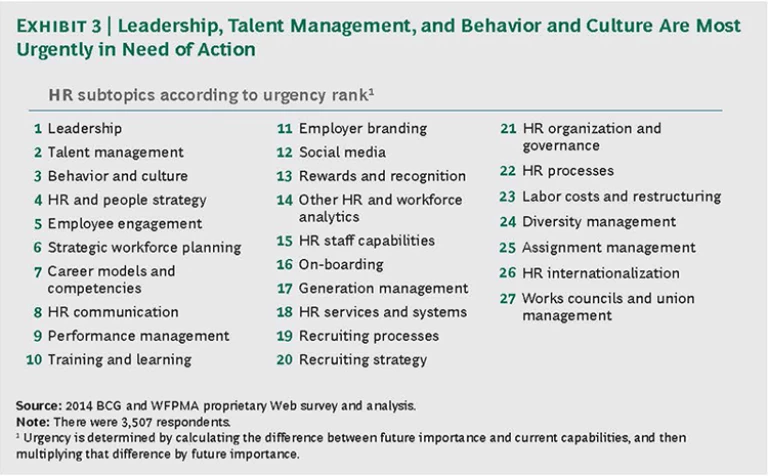

- Globally, the leadership and talent management topics are the ones in the most urgent need of action. Across industries and regions, most respondents identified leadership, talent management, behavior and culture, HR and people strategy, employee engagement, and strategic workforce planning as the topics that are most urgently in need of action by their organization.

- HR departments need to be more consistent in their investment decisions. Many organizations need to invest their efforts in HR topics more strategically to build capabilities. Among the three HR topics rated as most important (out of a total of ten), companies showed merely average capabilities, and they were not specifically targeting their investments to improve those areas.

- HR needs to listen more to internal clients. Non-HR respondents reported a strong need for action with regard to approximately 40 percent of HR topics, particularly in core HR capabilities, such as staff capabilities and communication.

Fundamentally, the report identifies three hallmarks of great HR functions:

- They connect by partnering with stakeholders inside and outside of the company to improve operational and financial performance.

- They prioritize by using data-driven insights to identify and focus on the most urgent HR priorities.

- They create an impact by using KPIs and steering tools to support the organization and its strategic goals.

The report also includes case studies of specific HR best practices from Deutsche Lufthansa AG, PepsiCo, and Transnet.

Key HR Topics

The Boston Consulting Group (BCG) has published an annual Creating People Advantage report—partnering, in alternating years, with the World Federation of People Management Associations (WFPMA) and the European Association for People Management (EAPM)—since 2007. In this year’s report, BCG and the WFPMA conducted a survey of human resources professionals and other business leaders around the world. The report summarizes the survey’s findings, provides a comprehensive snapshot of people management priorities and capabilities, and explores their link to companies’ operational and financial performance.

This report serves as an overview, with highlights of key findings. Follow-up reports will provide more detailed findings and in-depth analyses on specific topics.

Survey Methodology

More than 3,500 respondents from 101 countries participated in our online survey in 2014. (See Exhibit 1.) We also conducted 64 in-depth interviews with HR and non-HR executives at leading companies in a variety of regions. (For more, see the Appendix .)

To identify HR priorities, we analyzed ten broad HR topics, which were further broken out into 27 subtopics. (See Exhibit 2.) For example, the topic of training and people development includes three subtopics: training and learning, career models and competencies, and assignment management. This categorization allowed us to look at big-picture trends and to drill down into specific analyses. We asked the survey respondents to rank each of the 27 HR subtopics by its future importance, their companies’ current capabilities in the subtopic, and the levels of effort invested in the subtopic.

Exhibit 2 shows the ten HR topics ranked by respondents’ assessment of future importance. The 27 subtopics are color-coded according to the levels of effort invested. Interestingly, while levels of effort broadly link to future importance, there are notable exceptions. For example, leadership, talent management, and strategic workforce planning are among the highest priorities, yet they received only average levels of investment. Clearly, companies must be more consistent in their investment decisions.

In addition, we combined future importance and current capabilities into a single metric—defined as urgency for action—and ranked all 27 subtopics

Non-HR Respondents Say That Capabilities Need to Improve

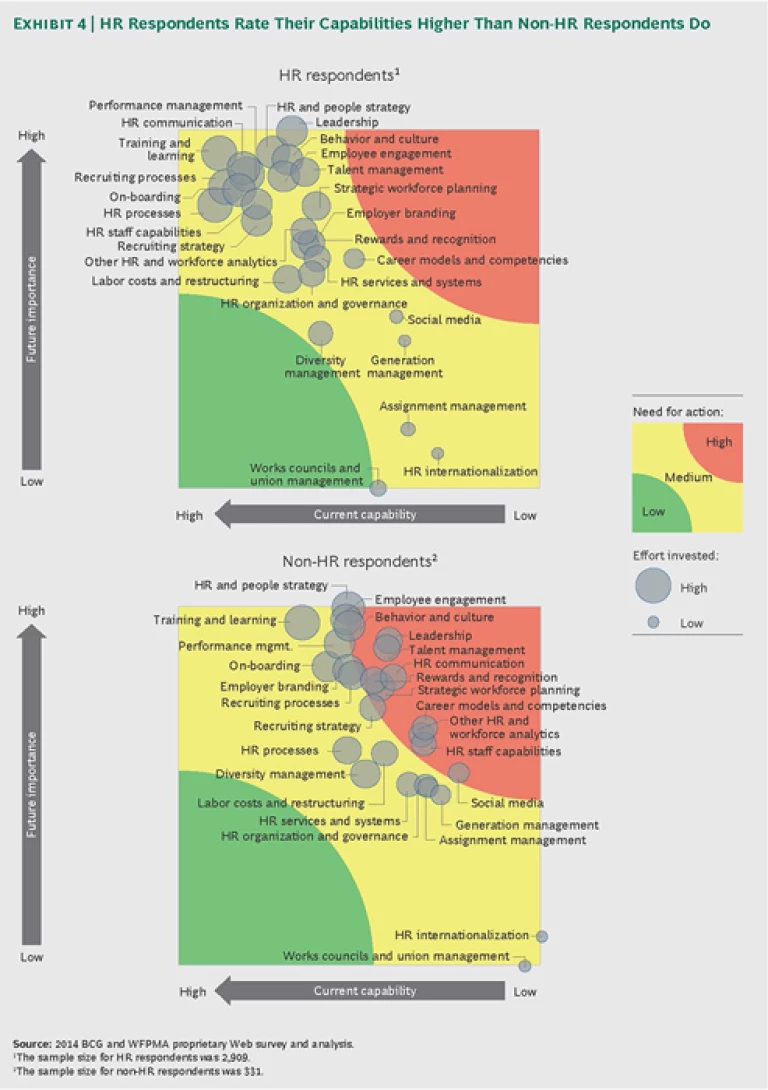

Both HR and non-HR respondents identified the same HR subtopics, such as talent management and leadership, as priorities—that is, the areas with the lowest current capabilities and the highest future importance. However, there were significant differences in the perceptions of their companies’ people management capabilities. (See Exhibit 4.)

Virtually across the board, HR respondents rated capabilities more highly than non-HR respondents. They also did not consider any areas to be in urgent need of action. By contrast, non-HR respondents categorized nearly half of the 27 subtopics as urgently needing action. This was especially true for talent management and leadership, two highly important subtopics for which non-HR respondents think their organizations show low capabilities.

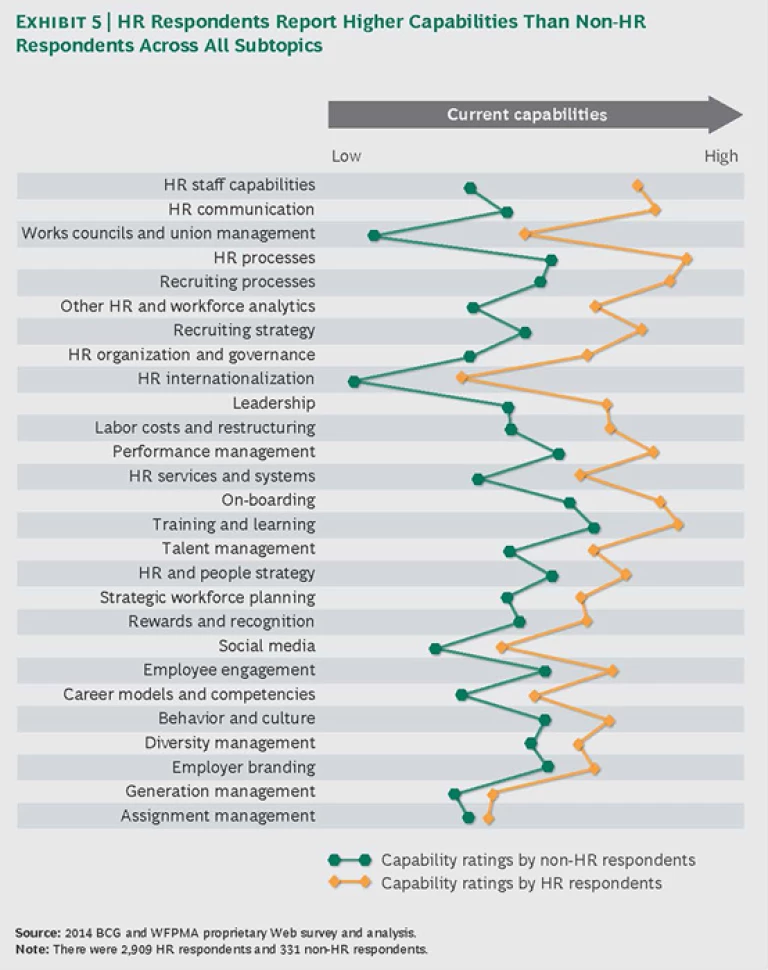

(For more on talent management, see “Decoding 200,000 Global Talent Profiles.”) Also, HR respondents attributed a higher importance to all subtopics—almost 10 percent on average—than did non-HR respondents, and they rated their capabilities as consistently higher.

DECODING 200,000 GLOBAL TALENT PROFILES

Over the past several years, talent management has been consistently rated as one of the HR subtopics in the greatest need of action. Companies are scrambling to develop strategies, programs, and measures to recruit, develop, and retain their top talent and keep them motivated at the same time—not an easy task.

In Decoding Global Talent: 200,000 Survey Responses on Global Mobility and Employment Preferences (BCG report, October 2014), we explored this issue in depth. We partnered with The Network—an association of more than 50 job boards worldwide, with more than 200 million visitors per month on all its websites—to conduct an online survey. The survey included 33 questions about talent mobility and job preferences, 13 of which looked at demographic factors, such as age, work experience, gender, education, industry, salary, and occupation. The result is a unique database that offers strategic insights for developing people strategies.

For example, the report shows worldwide trends in talent mobility across countries, age groups, and positions, among other factors. Global mobility is widespread, with 64 percent of job seekers willing to work abroad. The U.S. is the favorite work destination, followed by the UK and Canada. Germany is the fourth most popular country to work in and the top non-English-speaking market in the group.

One of the survey’s more striking findings has to do with what people say makes them happy on the job: increasingly, workers are starting to put more emphasis on cultural aspects and less on financial compensation. Out of 26 job elements, the single most important one for all people globally is appreciation for their work. (See the exhibit below for the top ten elements.) Good relationships at the office—whether with colleagues or superiors—are critically important and come in second and fourth, respectively. A good work-life balance is the third most important job factor. The implications for companies, economies, and individuals are significant and varied; addressing them will be key for future success.

Equally distressing, the strongest misalignment was in the area of HR staff capabilities, HR communication, works councils and union management, and HR processes. (See Exhibit 5.) HR and non-HR respondents agreed on the level of capabilities in the subtopics employer branding, generation management, and assignment management.

In many organizations, the HR function is perceived as not meeting the expectations of its internal clients. To address this misalignment, HR departments must better align with business units throughout the enterprise, to increase the impact of HR and generate stronger business performance.

The Link Between Financial Performance and HR Capabilities

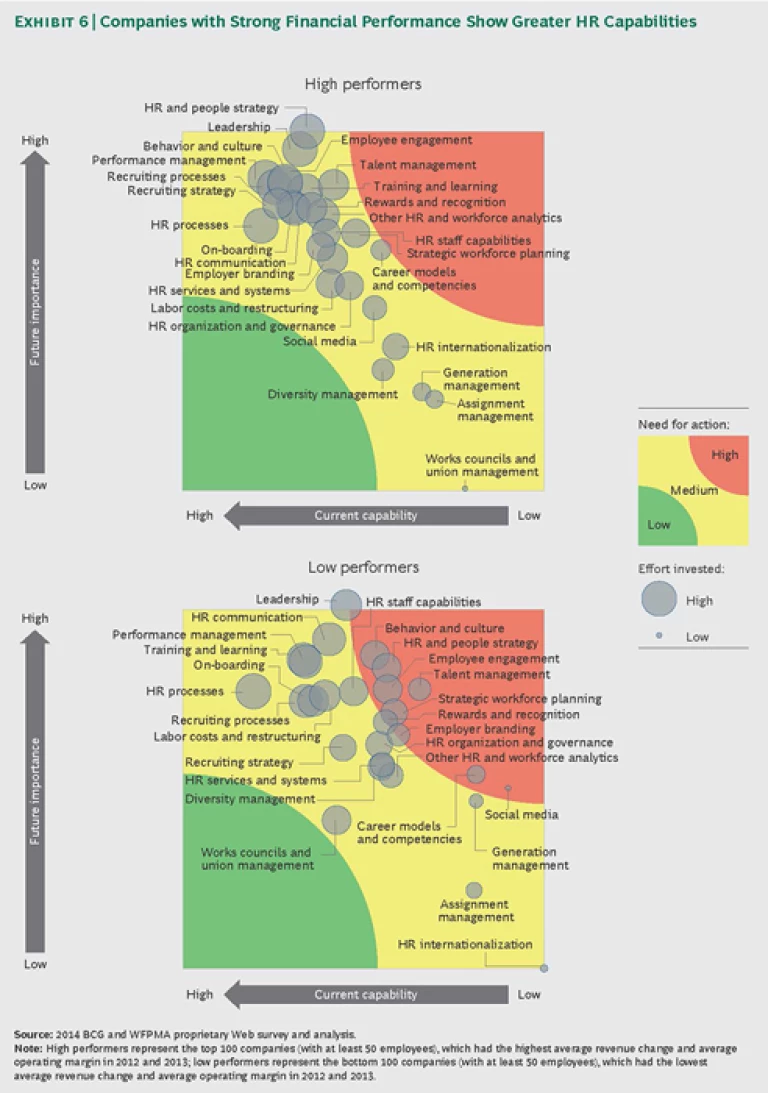

A central finding of our survey is the correlation between HR capabilities and financial performance. We segregated the top 100 and bottom 100 companies according to financial performance, as measured by average operating margins and average revenue changes during the previous two years (2012 and 2013), and we included only companies with at least 50 employees. (See Exhibit 6.)

We found that companies that are stronger in people management have a correspondingly higher financial performance. Among high performers, no HR subtopic is designated as being in urgent need of action.

In contrast, companies with the worst financial performance show a greater need for action across virtually all 27 HR subtopics, with seven clearly in the red zone and three more at the border.

This has been a consistent finding in previous Creating People Advantage reports and in publicly available research. Looking at the publicly listed companies that made Fortune magazine’s “Best Companies to Work For” ranking in 2014, and their share prices over the decade from 2004 to 2013, it is clear that the most successful people companies consistently outperformed the market, by nearly

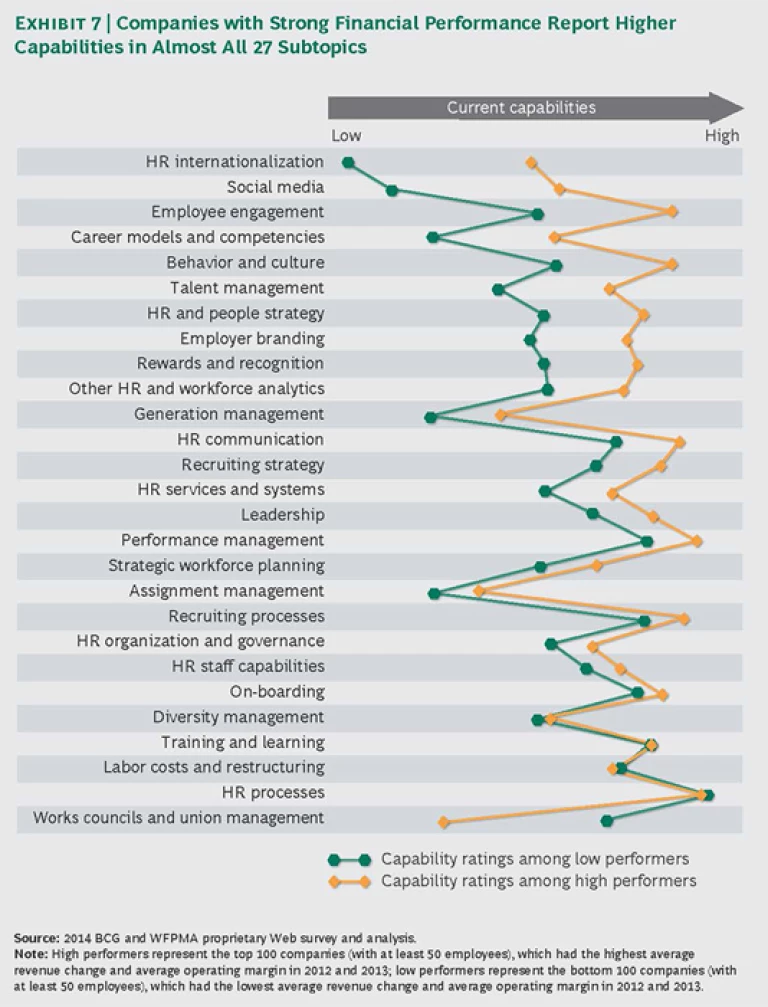

In our survey data, there was a troubling difference in capabilities between companies that are high performers and those that are low performers. (See Exhibit 7.)

This was greatest in HR internationalization, social media, employee engagement, career models and competencies, and behavior and culture.

High- and low-performing companies also have different priorities in terms of future importance. HR internationalization, HR and workforce analytics, recruiting strategy, HR and people strategy, and career models and competencies are significantly more important in high performers than in low performers.

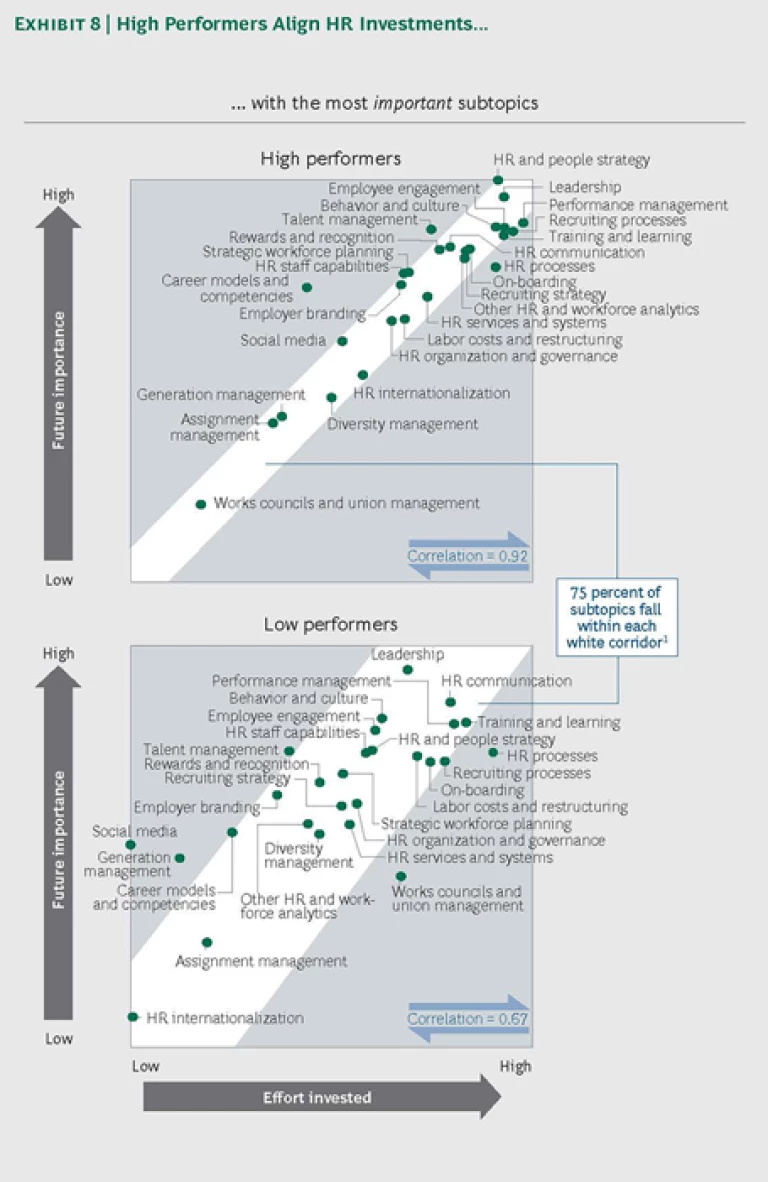

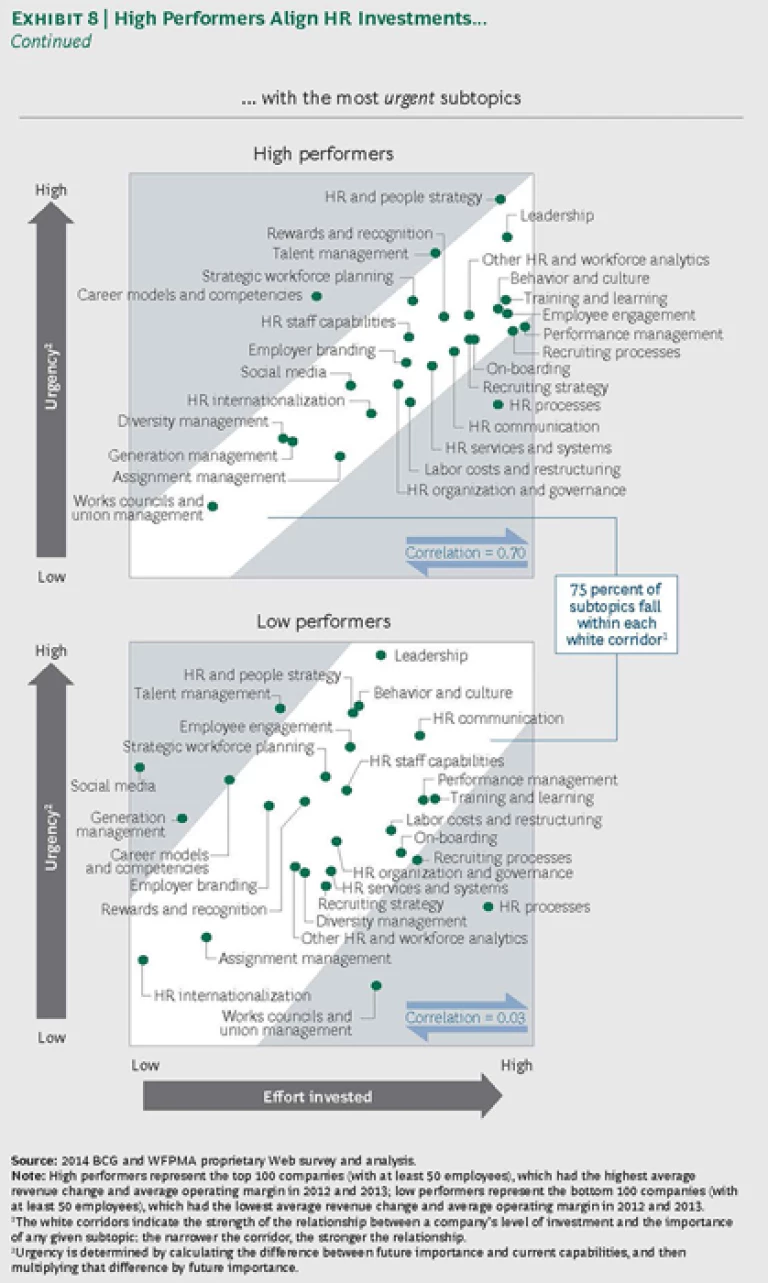

One possible explanation for the superior HR achievement of high performers is their strategic allocation of investment. (See Exhibit 8.)

Our analysis shows a strong relationship between the levels of effort invested and the future importance of the subtopics being addressed. That is, high performers are more strategic in the way they allocate their efforts; they take a systematic approach to improving capabilities; they are able to accurately distinguish high-priority topics from lower priorities; and they can then direct their resources accordingly, potentially improving their financial performance.

We found that low performers, by contrast, have a more arbitrary relationship between efforts invested and the importance of areas targeted for improvement. Investments tend to be misaligned; the most important issues don’t necessarily win the greatest investment.

This suggests that low performers don’t have a rigorous process in place for improving their people-management practices. Many companies lack a way to clearly identify the subtopics that are most important to their organization. They struggle to implement governance that effectively targets their resources, and they lack the discipline to enforce alignment with need over time—a necessity for the kind of sustainable improvements that can ultimately impact the bottom line.

The alignment issue also arises when looking at the urgency of specific HR subtopics. Again, top performers are more strategic in the way they invest their efforts, focusing on the subtopics that they deem to be most urgently in need of action.

For example, consider Pirelli, a leading tire manufacturer, which systematically prioritizes its HR processes to allocate investment according to urgency. As Christian Vasino, the company’s chief human resources officer, explains, “We conduct an annual internal survey to map the perceived sense of priority and satisfaction among 12 HR processes. The outcome of the survey was discussed within HR’s top management as a starting point for developing the people strategy.” Through this assessment, the company is now able to focus on its most urgent areas, which they define as strategic workforce planning, recruiting and on-boarding, training and development, and employee engagement.

HR's Business Impact

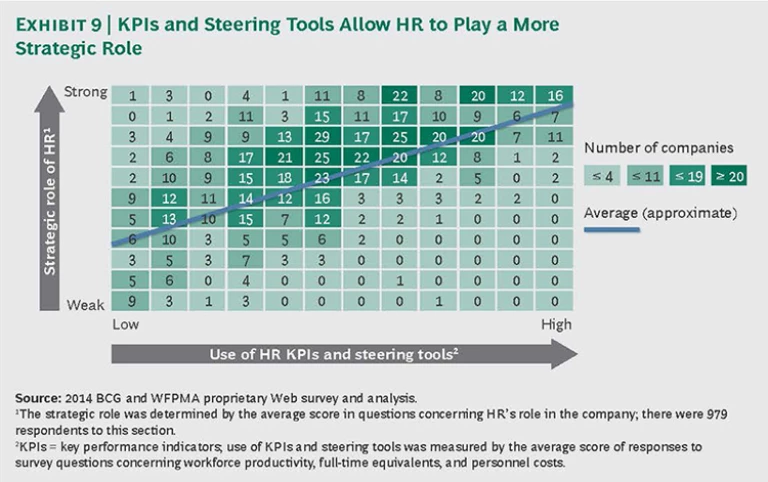

Another key finding is that HR leaders will have a seat at the table for strategic discussions only if they can demonstrate the business impact of HR. That is, they need to be able to quantitatively establish the areas in which HR supports the organization’s strategic decisions. Our experience has found that data-driven, analytical HR departments are more likely to play a strategic role in their organizations, and the survey data supports this. (See Exhibit 9.)

HR functions that use people-related KPIs and steering tools (such as simulations and forecasts) to measure areas such as workforce productivity and personnel costs, and then analyze and communicate the results throughout the organization, have a greater strategic role in the organization.

Yet our survey data also shows that using a data-driven approach is far from universal. Nearly half of the respondents (44 percent) said that if they use KPIs and steering tools, they do so only occasionally to track workforce productivity. An even larger proportion (55 percent) said that, at best, they use them only occasionally for tracking personnel costs—a relatively basic output metric.

An HR organization that does not use metrics and analytical techniques simply cannot play a strategic role in its organization. Without a clear, data-driven understanding of how the organization is leveraging its human capital, HR leaders have little to contribute to big-picture strategic discussions.

Such results reinforce a common stereotype of HR: that the function is better at working with “softer” aspects of human capital, such as training and development, and is less skilled at applying the economic logic required for higher-level areas, such as workforce productivity, planning, and forecasting.

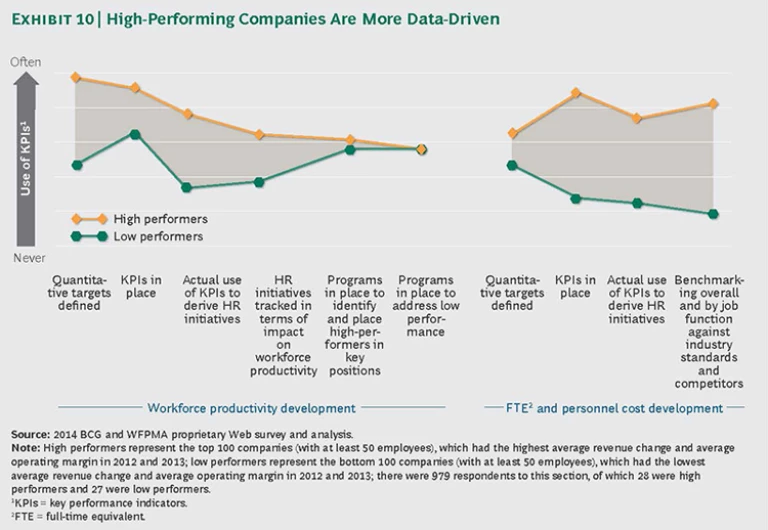

The use of HR KPIs and steering tools is yet another point of differentiation between high performers and low performers. (See Exhibit 10.)

That said, there is still room for improvement among the high performers. While these companies were far more likely to define quantitative targets and have KPIs in place, there was still a noticeable drop-off in the number of companies that take the next step—using those KPIs to formulate new HR initiatives. So, the low performers need to become more data oriented, and both high and low performers need to use that data to take action.

Key performance indicators are crucial in assessing HR impact, yet many companies struggle to ensure that they’re measuring the aspects of performance that truly matter. For example, many companies look primarily at the “input” elements of HR, such as head count or costs, rather than the “output” elements, such as productivity. They neglect to track the effectiveness of their HR spending to ensure that it supports the company’s strategic orientation. (For more on KPIs, see “ How Lufthansa Consolidated Its KPIs to Measure the Things That Really Matter .”)

Regional and Industry Considerations

To highlight the biggest priorities for companies in various regions and industries, we looked at all 27 HR subtopics, using our urgency metric to determine those with the greatest need for action.

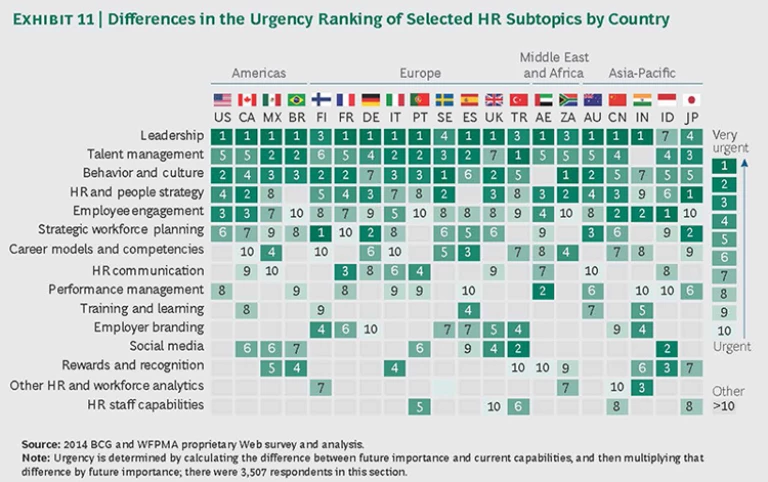

Regional: Leadership & Talent Management Show Urgency

Across most countries, the leadership subtopic was ranked by far as the one most urgently in need of action, and talent management was ranked the second most urgent. Beyond those clear-cut results, however, we found considerable differences in the rankings of subtopics across countries. (See Exhibit 11.)

For example, behavior and culture, as well as employee engagement, were all ranked as more urgent in the U.S. than they were in most other regions. In that market, growth is slowly returning and unemployment is easing. As a result, the competition for labor—particularly in skilled positions—is becoming tougher. Increasingly, some companies are finding that they have to manage their employees on a long-term basis.

In other markets of the Americas, such as Brazil, the focus is still primarily on talent management, given the shortage of candidates for many positions. “The challenge that we see is a huge lack of qualified professionals in Brazil, which is restraining Brazil’s growth and, consequently, the growth of Brazilian companies,” says Simone Cristina T. Salsa Nunes, a corporate strategic people development manager at Queiroz Galvão, a Brazilian conglomerate with investments in infrastructure, energy, food, steel, and shipbuilding industries.

Notably, rewards and recognition were ranked as more urgent in Brazil than in most other markets. This is primarily due to the country’s current economic situation, with relatively low productivity growth and increasing salaries. As Brazilian companies lose competitive ground, they must work harder to motivate their existing employees.

The talent management challenge also exists for Asian countries. According to Joseph Bataona, a human resources director at Indofood Sukses Makmur, “Indonesia has a talent crisis at the national level—in almost every sector, including government. The shortage of talent is not being addressed in higher education, whereby graduates are not really ready for the professional world. There is also a shortage of vocational training. Companies really have to invest more in developing people, even at the entry level.”

In many European countries, by contrast, demographic challenges, such as those posed by an aging labor pool, are compelling companies to adopt strategic workforce planning, which was ranked as far more urgent in Germany, among others, than the global average. (See “The Global Workforce Crisis.”)

THE GLOBAL WORKFORCE CRISIS

In The Global Workforce Crisis: $10 Trillion at Risk (BCG report, June 2014), BCG examined long-term labor issues in 25 of the world’s major economies, looking at imbalances in supply and demand over the next 10 to 20 years. As shown in the exhibit below, which summarizes the findings for 15 countries, some countries are likely to experience tremendous labor shortfalls. The workforce in Germany, for example, will likely fall 4 percent short of the country’s needs by 2020 and 23 percent short by 2030. Brazil is expected to experience a shortfall of 7 percent of its workforce needs by 2020 and 33 percent by 2030. In some of these countries—notably Germany—companies are already feeling the pinch, struggling to find qualified people to meet workforce demand.

These dramatic shortfalls only underscore the importance of subtopics directly related to long-term human capital planning and preparation, such as strategic workforce planning, diversity, and generation management. Yet most organizations in northern Europe—with the notable exception of German companies—are not prioritizing those topics. (See “ Transnet Has a Clear View of Future Employment Needs. ”)

Countries in southern Europe are facing a different set of challenges, namely sluggish growth and high unemployment. In general, the closer a country is to economic crisis, the more companies in that country will need to differentiate among their employees, to ensure that they can keep the most promising workers in the event of staff reductions.

Industry: Energy and Financial Institutions Stand Out

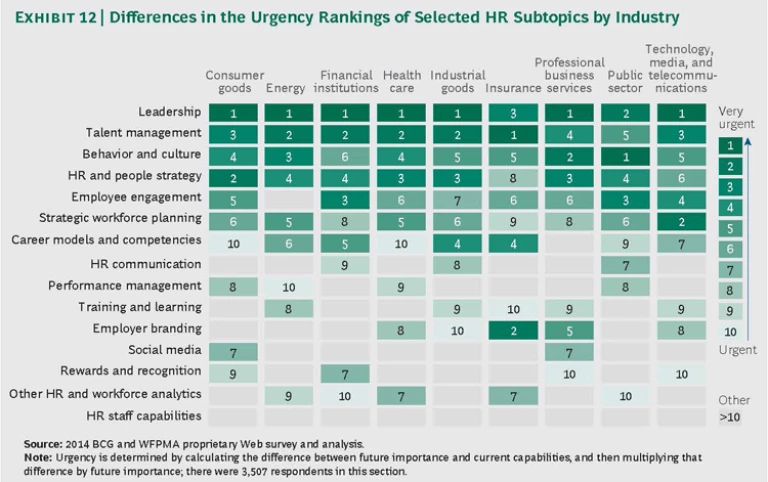

An industry breakdown shows similar differences among the relative levels of urgency of specific subtopics. While leadership, talent management, and behavior and culture were ranked as the three most urgent across most industries, we uncovered several key insights. (See Exhibit 12.)

In the energy sector, leadership was rated the most urgent topic. Leaders in the oil industry are facing significant challenges, such as growing demand for environmentally sustainable processes, bad publicity from recent spills and other accidents, and pressure on financial results. Because of these factors, they have to move from traditional (technical) competencies in the sector to more twenty-first-century skills, such as how to manage uncertainty. Also, in the utilities sector, there are significant uncertainties with respect to supply, which means that leaders must navigate among, and negotiate with, multiple stakeholders. Talent management was the second most urgent topic in the energy sector, mainly due to the lack of talent—especially skilled technical workers—needed to meet the strong demand for new oil and gas projects.

Among financial institutions, several differences stand out. These companies are slowly resuming growth after the financial crisis. Accordingly, rewards and recognition were ranked as more urgent priorities than in other industries. By contrast, behavior and culture were seen as less urgent than in other industries. Given the fact that many financial-services companies promised to change the way they work after the crisis, this subtopic should be a bigger priority in the sector.

What Sets Great HR Functions Apart

Based on BCG’s experience, and supported by the survey data, we see that great HR functions are critical differentiators that separate high-performing companies from the rest. Collectively, the three ideas below describe best-in-class HR functions.

- Connect. An HR department needs to connect with internal clients to ensure that its HR and people strategies are clearly linked to the overall business strategy. A fundamental component of this is getting the basics right. That is, if HR is to have credibility as a true strategic partner with the business, it must first establish strong processes and develop core capabilities, particularly in the areas of recruiting and communication.

- Prioritize. HR also needs to identify the most important and most urgent priorities for its organization and then target investments accordingly. As the survey findings show, talent management, leadership, and employee engagement are the topics that virtually all HR departments will need to focus on. Strong HR departments have precise and trackable leadership-development initiatives in place, along with enterprisewide training measures and firm control over internal mobility. These departments shape engagement and leadership behaviors to foster a more vibrant and productive corporate culture.

- Impact. Robust HR departments generate and report people-based KPIs, which provide the data for formulating strategic actions and ultimately impact the business. This is particularly true for strategic workforce planning, which is increasingly important for most companies. People analytics—defined as the increased use of data to generate insights on people management processes—is now taking off in terms of use and importance. Just as other functions of a company increasingly rely on sophisticated algorithms in areas such as pricing and supply-chain management, HR analytics are becoming an indispensable tool to help HR functions impact the business.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the many executives who shared their thoughts during interviews, as well as the respondents who completed the online survey. The insights and expertise of these individuals have greatly enriched this report. A list of interviewees who were willing to be named is provided in Appendix II. We thank Jacqueline Betz, Nico Geisel, Katrin Jaskiewicz, Julie Keveny, Charlotte Pallua, Cleo Race, Samuel Schlunk, Susanne Schrader, Carlos Tielesch, and other BCG colleagues for their research and analysis, as well as Jeff Garigliano for his help in writing this report.

The authors also thank the members of the BCG and WFPMA steering committees for their help with this project. From BCG: Jens Baier, Vikram Bhalla, Grant Freeland, Pappudu Sriram, Peter Tollman, Dean Tong, and Roselinde Torres. From WFPMA: Max Becker, Izy Behar, Patrick Belpaire, Stephanie Bird, Even Bolstad, Catherine Carradot, Joe Gerada, Ute Graf, Soli Johansson, Roberto Luna, Leena Malin, Kim Staack Nielsen, Vanda Pecjak, and Svetla Stoeva.

Moreover, we are grateful for the support we received from various BCG colleagues in coordinating and conducting interviews and for their expert advice: Alfonso Abella, Alexandre Amoukteh, Vassilis Antoniades, Monique Baars, Jens Baier, Julio Bezerra, Massimo Busetti, Davide Corradi, Emanuele Costa, Guido Crespi, Christopher Daniel, Filiep Deforche, Camille Egloff, Maxim Fedotov, Alessandra Ferraro, Gabriele Ferri, José Antonio Gil, Alberto Guerrini, Tatu Heikkila, Jörg Hildebrandt, Adrian Hofer, Jens Irion, Chryssos Kavounides, Meg Kedrowski, Klaus Kessler, Ivan Kotov, Daniel López, Manuel Luiz, Jussi Mattsson, Stéphanie Mingardon, Riccardo Monti, Matthias Naumann, Mikko Nieminen, Gözde Yalazi Özbek, Christina Paraskevopoulou, Knut Olav Rød, Michael Seeberg, Alexander Schudey, Achim Schwetlick, Michael Shanahan, Art Uprety, and Jan Dirk Waiboer.