If you live in a major city like New York, Singapore, São Paulo, or Berlin, it’s likely that many of the people you run into in the course of a regular business day are foreign born. It might be the barista who sells you coffee on your way to work. Or the businesswoman next to you on the commuter train. It might be the head of your department or the CEO of your company. You might be the person from another country.

Related Content

- German Workers

- Swiss Workers

- US Workers

- UK Workers

People become expatriates for a variety of reasons—to escape political strife, improve their economic circumstances, and sometimes, to have a chance for a life-changing experience. With workforce gaps of one type or another starting to dot the world map, would-be expatriates may be in a better position to find work that suits them, especially as information about jobs globally becomes exponentially more available.

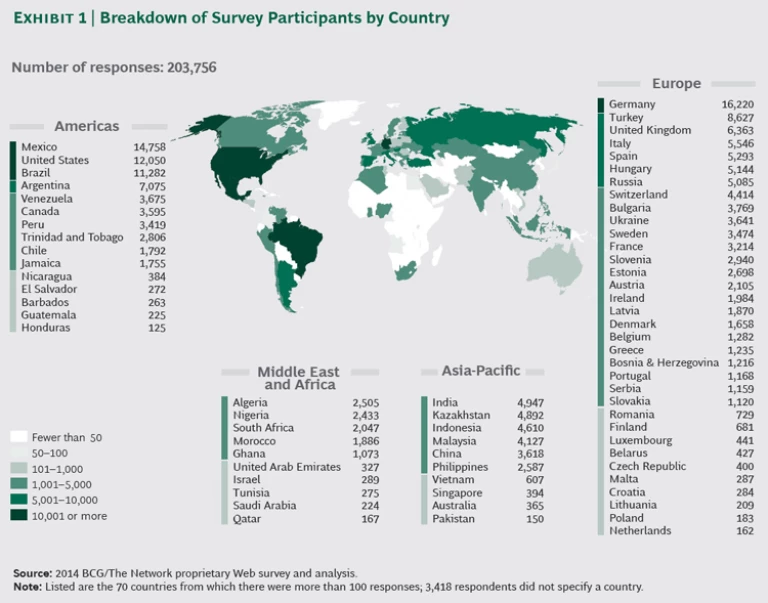

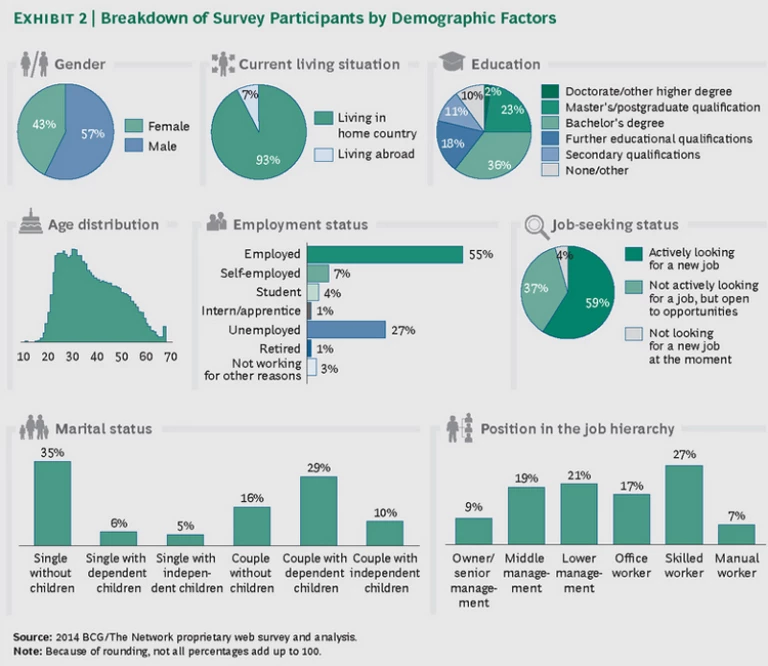

Together, The Boston Consulting Group and The Network conducted research on today’s global workforce—everything from what people in different parts of the world expect of their jobs to what would prompt them to move to another country for work to the countries they would consider moving to. More than 200,000 people from 189 countries participated in the survey, creating a multidimensional picture that employers may find useful both for recruiting internationally and for redesigning their overall people strategies. (See Exhibits 1 and 2 and “A Unique Data Cube: Decoding 200,000 Talent Profiles.”) BCG and The Network also held follow-up interviews with more than 50 study participants, who represent a broad mix of nationalities, ages, personal living situations, employment status, and education. (See the Appendix for the survey methodology.)

A Unique Data Cube: Decoding 200,000 Talent Profiles

“Talent management” has become one of the most used buzz words in HR. Companies are scrambling to develop strategies, programs, and measures to recruit, develop, and retain their top employees and keep them motivated at the same time—not an easy task.

BCG and The Network believe that taking a data-driven approach can help solve these challenges. Talent is a company’s most precious resource, but its definition varies from one company to another. Our joint research explores overall workforce data relevant to companies. This publication is based on more than 200,000 replies to an online survey containing 33 questions, of which 13 addressed demographic factors like age, work experience, gender, education, industry, salary, and occupation—questions that can be filtered and combined to group the data. The result is a unique data cube that offers true strategic advantages for developing people strategies.

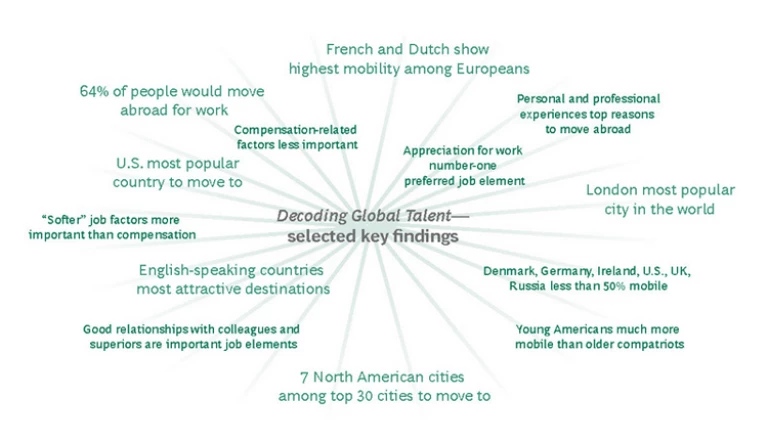

The picture that emerges is of a global workforce that is stunning in its diversity—but that is also in broad agreement in certain areas. The areas of agreement include a high level of willingness to work abroad; the greater appeal of certain work destinations than others; the importance to would-be expatriates of broadening their personal experiences; and the growing interest in “softer” workplace rewards. These topics are discussed in turn below. The report concludes with a perspective on what the emerging global attitudes toward work will mean for economic policy makers, company executives, and job seekers in the future.

Workers' Increasing Mobility

A willingness to work abroad has become the new normal, at least among people looking for new job opportunities, who represent the majority of the survey’s participants. One in every five participants already has international work experience, and almost 64 percent said they would be willing to go to another country for work. (See Exhibit 3.)

In some countries, the eagerness to work elsewhere is impossible to miss. Mihaella Ciornei, a 23-year-old account manager at a securities firm in Romania and part-time anthropology student, says a lot of her friends have left to look for overseas opportunities. “They’re all over Europe, they’re in America, Australia,” she says. “They want to see the world. They are gone.” Ciornei already has a mother living in Italy and a sister living in France, and she herself is among the 81 percent of Romanians who say they would be willing to work abroad.

The proportion of people willing to work abroad is particularly high in countries that are still developing economically or are experiencing political instability. For instance, more than 97 percent of Pakistanis say they’d be willing to go abroad for work.

But there is also a very high willingness to work abroad in some countries that aren’t struggling with major political upheaval. For example, about 94 percent of survey respondents in the Netherlands say they would consider moving to another country for work. In France, where the economy has been showing signs of stagnating, the same proportion (94 percent) is willing to leave home at least temporarily. “Depending on the project, I’m ready to pack a bag and go tomorrow,” says Alexis Sebaoun, a 29-year-old engineer living in Marseille who has already worked in Spain, Argentina, and the UK in his short career.

On the other hand, people in the U.S., Germany, and the UK—three economies that have rebounded more convincingly—aren’t nearly as willing to go abroad for work. Barely a third of U.S. respondents say they’d consider the idea, and only about 44 percent of those in the UK and Germany say they would be interested in taking a job in another country. The reasons for the lower numbers differ, but many people in these countries say economic stability and the comfort of home keep them from considering a job abroad.

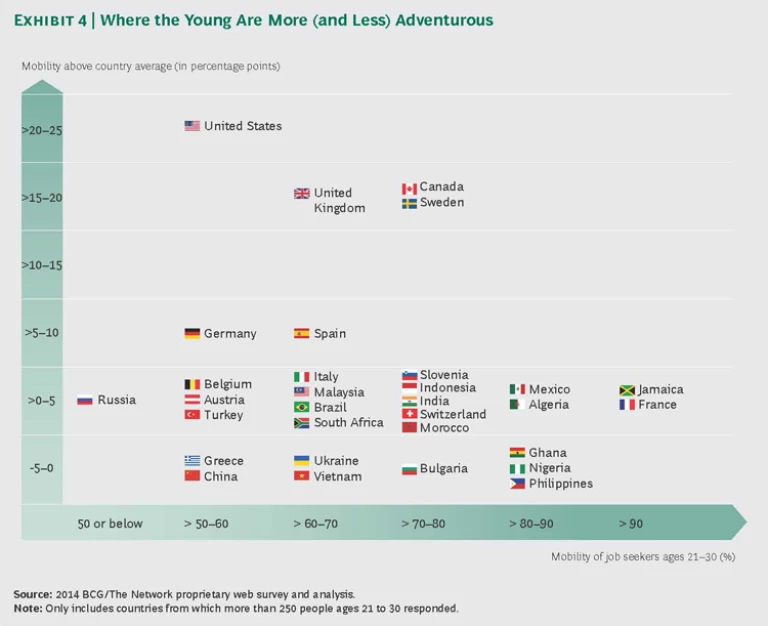

Movement of Youth

In most countries, young people are more mobile than their older compatriots. One of the biggest differentials is in the U.S. At 59 percent, Americans 21 to 30 are far more willing than Americans in general to consider opportunities abroad, possibly because of the difficulty many of them have had in getting their careers started in the wake of the financial crisis. Partly in reaction to this, many educated young Americans now consider nontraditional starts to their careers, for instance, through temporary overseas assignments with nonprofits like Teach for All.

Young people in Germany are much more conservative about the idea of working abroad; while there is a difference in the willingness to do so between younger Germans and the country as a whole, the difference is a relatively small 8 percentage points. (See Exhibit 4.) This may be explained by Germany’s singularly strong performance in the wake of the financial crisis and its aura of economic security. The country has the lowest unemployment rate in Europe for people under 25.

More and Less Mobile Occupations

People who work in engineering and technical jobs—in the information technology and telecommunications fields, in particular—are the most likely to say they would be willing to go abroad (roughly 70 percent of engineers say this). The world is hungry for what these workers have to offer, and engineers may in turn sense that they have a chance to significantly increase their earnings by going to places where there is a high demand for what they do, such as Silicon Valley in the U.S. and Silicon Roundabout in the UK.

At the lower end of the mobility spectrum are those in the medical and social work fields. Only about half of the workers in these highly regulated areas say they would be willing to go abroad for work. This may be a cause for concern in the many countries facing physician and social-worker shortages in coming years. Indeed, some countries are embarking on programs to attract qualified health-care workers from abroad. Germany, for instance, is tapping the Asian labor pool for Vietnamese workers willing to learn a new language, emigrate, and work as elder-care nurses in rural areas of Germany.

The Appeal of Specific Foreign Destinations

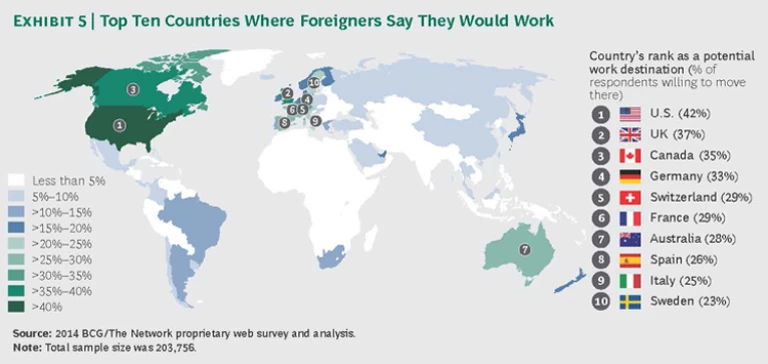

The United States is the destination with the highest appeal to foreign workers. Of all respondents, 42 percent say the U.S. is one of the places they would consider moving to. (See Exhibit 5.) The U.S. maintains its appeal among workers in many impoverished nations, including Nigeria, Ghana, Nicaragua, and Honduras. Sixty percent or more of respondents from those nations say the U.S. is a place they would move to for work. The UK and Canada get the next highest declarations of interest from survey participants: 37 percent and 35 percent, respectively. The UK, Canada, and the U.S. are all in the top ten in terms of nominal GDP, per capita GDP, or both. They all also benefit from being largely English-speaking at a time when English is the most frequently taught second language.

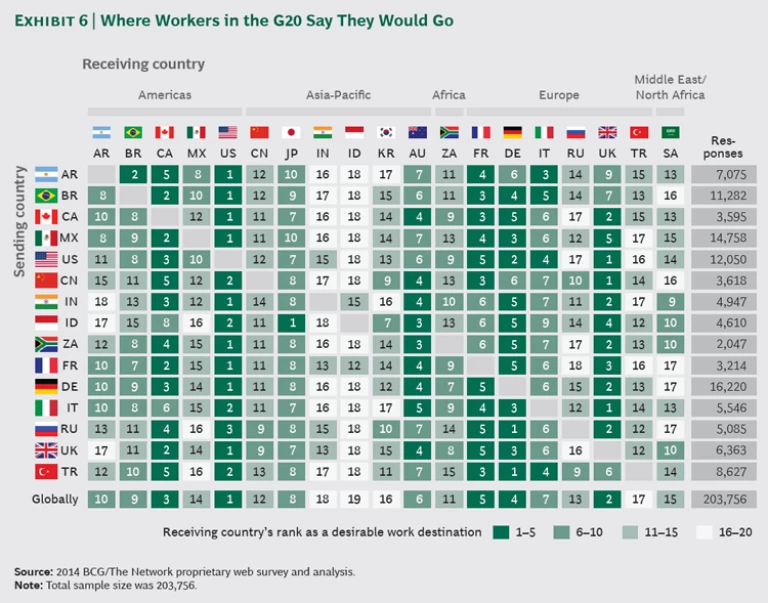

Among workers in large economies—the so-called G20—the U.S. is often the most popular destination. (See Exhibit 6.) Mexicans, whose focus on financial factors is at the high end of all the nationalities in the survey, put the U.S. first as a possible work destination. So do people from France and from India. The U.S. is the second most popular work destination for people from China after the UK.

French, Indian, and Chinese respondents are also positively disposed toward work opportunities in the UK, with 53 percent of people from France, 43 percent of people from India, and 42 percent of people from China saying they would consider work opportunities there. The UK also appeals to workers in Africa. “England is a country of opportunity,” says Humberto Santos, a 57-year-old originally from São Tomé and Príncipe, a central African island nation, who is in England and recently got a job there as an aircraft engineer, maintaining planes and repairing defects identified in flight reports.

As for Canada—where French retains its status as an official language alongside English—59 percent of French respondents to the survey say they would consider working there. Other people for whom Canada holds appeal are Mexicans, South Koreans, Saudi Arabians, and Britons. Philip Webb, who works in the IT department of a bank in Toronto, is among those from the UK who have found their niche in the country. “Canada has all the good things they have in any other country and none of the bad,” says Webb, 43.

Among non-English-speaking countries, Germany (named by 33 percent of respondents), Switzerland (29 percent), and France (29 percent) have the most appeal. Germany is particularly attractive to Italians, Russians, and Turks, who have long seen Germany as a promising place to work, and it is also starting to appeal to others, such as Mexicans. Explaining Germany’s appeal, Matej Hrapko, a native of Slovakia, says, “Germany is attractive because it is the most successful country in the European Union at the moment.” Hrapko, 35, lives near Munich with his wife and two children and works as a mechanical engineer.

The Asia-Pacific region doesn’t generate as much interest as a possible work destination as the U.S. or Europe, largely because of the perceived difficulty of learning Asian languages (a perception that is particularly strong in Europe and the Americas, where most of the survey participants are based). China, for instance, isn’t the top work destination for people in any of the G20 countries, and Japan ranks first only among Indonesians.

However, some fast-growing Asian countries are starting to reclaim workers they have lost. “This is probably the craziest place in the world right now—if you’re looking for growth, you come to China,” says 31-year-old Xiaomu Liu, who just moved back after six years working in the Canadian oil and gas industry and after earning his MBA in the U.S. Xiaomu says he was concerned that if he stayed in North America much longer, Chinese hiring managers wouldn’t think he had the right experience for the Chinese market, and he would lose his chance to get a job in the rapidly expanding economy of his native country. (For the cities workers would most like to move to, see “The Other Part of the Question: Picking a City to Work In.”)

The Other Part of the Question: Picking a City to Work In

Ask someone “Where else besides your home country would you work?” and you are likely to get a two-part answer. The first will be the countries on the person’s short list. The second will include the cities he or she finds appealing.

London and New York are the metropolises that came up most often when we asked survey respondents (without making any suggestions) which cities they would consider moving to for work. (See the exhibit.) This is probably no surprise: in addition to being global centers of business and culture, London and New York have the biggest foreign-born populations of any cities in the world, with about 3 million foreign-born people each. This immediately makes those places seem more welcoming—or at least less intimidating—to people from other places.

“If you ask a young person in this country, ‘Where do you want to go in the UK?’ they’ll never say Liverpool or Manchester,” says Ali Aslan Gümüş, a 45-year-old who has worked in Brussels and is now back in his native Turkey. “They all say London because of the Turkish population that’s over there and the cultural harmonization.”

Given that one of the top reasons for moving abroad is acquiring work experience, it isn’t surprising that certain cities come up again and again. In terms of reputation, it’s hard to beat Zurich if you’re a banker, Los Angeles if you’re an aspiring film actor, and Singapore if you’re an international customs broker. A few years in one of these cities can be career-making.

But mobile workers are not focused strictly on their careers. They are equally interested in broadening their life experience—and that can impel them toward cities where there is more freedom than in their home countries. “People are very open-minded here—you can see it in how they dress and how they behave,” says Matej Hrapko, 35, a Slovakian who lives and works in Munich, the fourteenth most-cited city in our survey. “It’s a very cosmopolitan city from my point of view.” Germany has two cities in the top 15, the same number as Spain and behind only the U.S., which has three.

The sheer uniqueness of certain cities gives them an almost mystical appeal. Consider Paris, with its storied history the third most-cited city in our survey. Graham Campbell, a 53-year-old U.S. resident who is originally from Canada and is currently out of work, says he and his wife would be tempted if a job in the French capital presented itself. “It’s an interesting city, inspiring to the imagination,” Campbell says. “It’s one of the only cities I’ve been in where you can make four right turns and be in a completely different place. That’s pretty exciting.”

The Desire to Broaden One’s Personal Experience

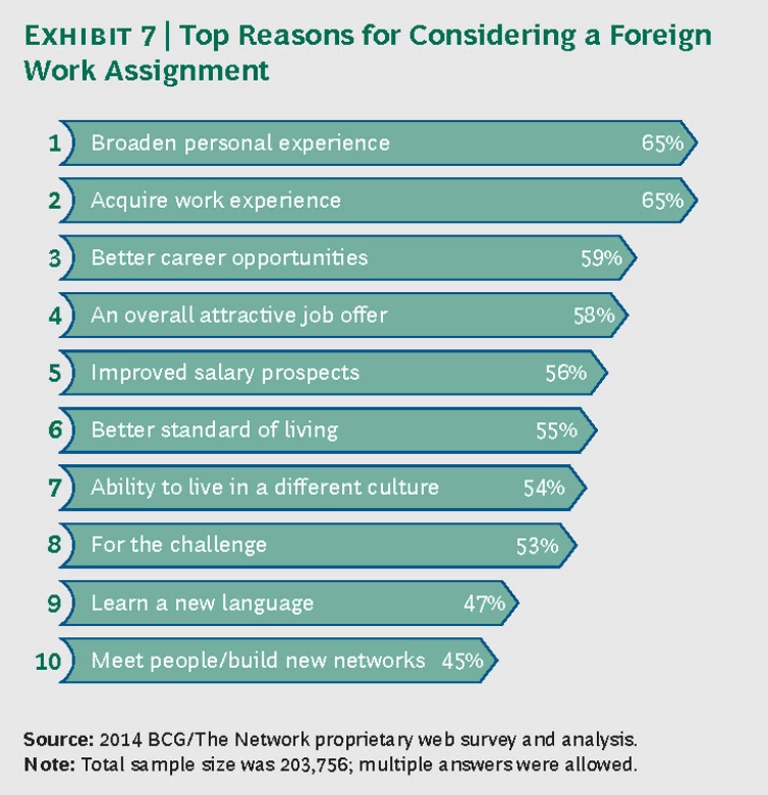

Why would people be willing to uproot themselves and head to a foreign country for work? For many (65 percent), the answer is personal: they want to broaden their life experience and that of their families.

“I would like to bring up my kids to be global citizens,” says Mpho Hlalele-Banda, a 37-year-old single mother in Johannesburg who in the past has worked as a communications and events specialist. “I would love countries that offer them that opportunity.”

This idea is echoed by some people who have already left home. “We really like the international atmosphere,” says Anne Granelli, 44, a Swedish biomedical researcher who travels around the world for work and now lives in India (after a previous stint in Canada) with her four children and husband, a telecommunications executive. “It is a great opportunity to get different views and learn a lot.” Granelli’s children—ranging in age from 5 to 14—now attend an international school in New Delhi; all have learned English and the youngest ones have picked up some Hindi.

An equal proportion of people—two-thirds—also view working abroad as a way to acquire professional experience. Better career opportunities, including the chance to run a business or advance through the ranks, figure prominently among professional motivations. (See Exhibit 7.)

The importance of these factors varies by country. In parts of Europe that are doing well economically, people tend to be influenced less by financial factors when deciding whether to take a foreign assignment and more by the chance to broaden their personal experience and live in a different culture. For instance, less than a quarter of Germans or Swiss who are open to working abroad say a better salary would factor into their decision to do so.

Worldwide, the number of people who say that a better salary would tempt them to work abroad is much higher, at 56 percent, and is higher still in some countries of the Americas (Mexico, Peru, and Argentina) and Asia (Malaysia and the Philippines), where per capita income is at the lower end of the spectrum. Ukrainians and Venezuelans, buffeted by some of the highest levels of economic and political uncertainty of any nationalities in the survey, are also among those most likely to say they would move for a better salary or standard of living.

Globally, 28 percent of all respondents say they would work abroad to gain access to a better educational system. The proportions are especially high in parts of Africa and in two Asian nations, Indonesia and Vietnam. Almost half of all Vietnamese willing to move abroad for work say the prospect of having access to a better educational system would be a factor.

To some, getting access to a better health-care system is likewise a reason to pull up stakes. For instance, more than half of respondents in Greece and Venezuela say they might take a job abroad to get access to better health care. Health care matters even more in Bulgaria, an economically troubled European nation where almost two in every three respondents say they would factor health care into their decision to work abroad.

Job Preferences: The Growing Importance of “Softer” Factors

One of the survey’s more striking findings has to do with what makes all respondents—not just those willing to move abroad—happy on the job. The survey provides compelling evidence that workers are putting more emphasis on intrinsic rewards and less on compensation.

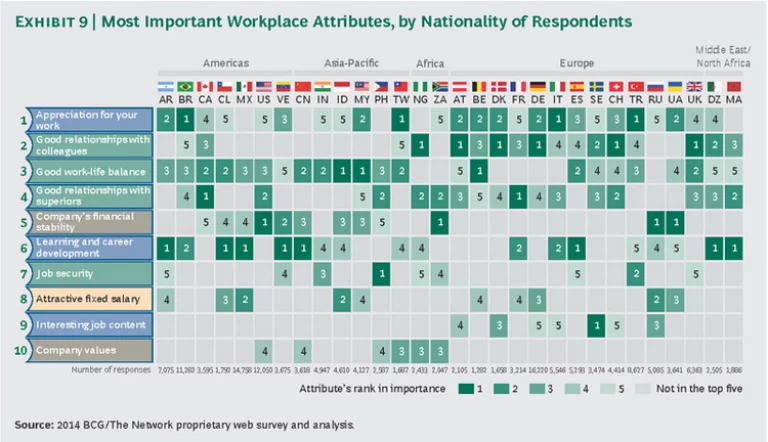

Globally, the most important single job element for all people is appreciation for their work. (See Exhibits 8 and 9.) To Tarik Aboussahel, 38, this is a basic human need. “What you do is what you are and what you are is what you do,” says Moqtad, who works as a logistics supervisor at a paint company in his native Morocco. “You must be appreciated.”

When people feel appreciated, their job satisfaction skyrockets. Dina Kiseleva, a 37-year-old interpreter from Russia, recalls the accolades she received when working as an English teacher at a university language center in Bangkok. “I was performing my job well, and they [the university administration] immediately started rewarding me—telling me I was a top-ten teacher and giving me the student groups and extra groups I wanted. My bosses had a really positive attitude toward me. I felt very appreciated and excited.”

Workplace Relationships

Along with appreciation for one’s work, good relationships in the workplace—whether with colleagues or with superiors—are critically important. “I really like that teamwork experience, especially when it’s multidisciplinary,” says Meera Bhagauti, a 43-year-old from Canada who lives in Los Angeles, is a PhD candidate in business psychology, and is training to become a certified practitioner of Ayurvedic medicine. As for relationships with superiors, it’s “important to me because I would like to learn and grow” and having the right supervisor “can help facilitate that,” she says.

Bhagauti’s view that “money isn’t everything” is typical of many workers today. Indeed, for most workers, compensation-related factors—including performance bonuses, health care insurance, paid time off, and the generosity of any retirement plan—don’t even make it onto their list of top-ten priorities.

After appreciation for work and relationships with colleagues comes another soft factor, work-life balance. As 39-year-old Nicole Dessain puts it, “I am not willing anymore to get up every Monday morning at 4 a.m. to head to the airport.” Dessain, a German expatriate, lives in Chicago with her American-born husband and recently went into business as an independent consultant. Compared to when she was in her twenties, she says, “The whole aspect of work-life integration has become more important to me.”

One tangible work attribute that retains high importance globally is learning and career development. “To me, it is the most important thing,” says Alejandro Vega, a 25-year-old supply-chain analyst from Mexico who is now working in Colombia. In putting career development first, Vega is like most people in Mexico, in many South American and European countries, and in China.

How Priorities Shift with Age and Position

While the interest in intrinsic work rewards is unmistakable, various factors influence the importance of the different attributes. One obvious factor is a worker’s age. Although an appreciative atmosphere is always near the top of the list of desired workplace attributes, other factors rise and fall in importance as workers go through their careers and gain experience. For instance, career development fades as a priority once workers grow out of their thirties. Work-life balance, too, rises in importance in certain periods—during child-raising years, for instance—and diminishes in others. But as workers age and family responsibilities ease, people again become more focused on the relationships they have at work and on the extent to which the work itself is holding their interest.

Another factor that seems to influence the weight that workers assign to different job attributes is their position within the organizational hierarchy. Workers lower down on the hierarchy assign more importance to their relationships with colleagues than to their relationships with superiors—exactly the opposite of higher-level managers—and they focus on factors that wouldn’t usually matter to an executive or a high-level manager.

The most obvious example of something that matters more to a lower-level worker than to an executive is job security. Job security is at the top of the list for manual workers and almost as important to office workers, but it isn’t a big concern to people in top management positions. With their skills and connections, people high up on the organizational ladder may believe that they could easily find a job elsewhere if they had to. Retaining these exceptionally talented people, given the expanded opportunities they have in a more global economy, will be at the core of the challenges that HR departments face over the next decade. (See “For HR Departments, It’s Time to Change the ‘Total Offer.’”)

For HR Departments, It’s Time to Change the “Total Offer”

There’s no question that there’s been an evolution in what workers value. What’s less clear is whether companies are moving to address the shift.

Even as employers have begun to modify the branding they use to recruit workers—correctly anticipating the shift to a postcrisis world in which money isn’t everything—companies have not really done much to push their reward systems toward new and compelling “total offers” that include many of the attributes relating culture, relationships, and appreciation that employees covet these days. Instead, company rewards are still largely built around compensation, and the culture inside many companies remains hierarchical, with complex guidelines, limited flexibility, and highly political agendas. It’s the rare employer that has found a way to institutionalize appreciation—the attribute that workers, especially younger workers of Generation Y, now seem to crave.To retain the best employees and keep them motivated, companies will have to come up with new strategies to keep their employees engaged. This isn’t to say that companies are entering an era of diminished status for compensation specialists, so prominent in the HR function now. Money may not be everything but it still matters, and compensation experts will still be essential.

But there need to be other kinds of expertise, too. In particular, HR needs to find ways to get more involved in shaping corporate culture, in encouraging meaningful relationships between and among bosses and workers, and in ensuring that appreciation for a job well done gets the company-wide attention it deserves. Otherwise, the most talented employees will leave and companies will face a strategic disadvantage.

Companies also need to take account of the varied reward mechanisms that are effective depending on workers’ career stage, management level, and nationality. This will be a big change for many HR departments, requiring fresh thinking and new areas of analysis, but the best will find ways to get it done.

Decoding the Impact

The looming global workforce shortage has important implications for three constituencies: economies, companies, and individuals.

Economies (countries) will need to find ways to attract and, especially, to retain their most talented and highly skilled people. Building attractive cities to live and work in, strengthening the education sector, and ensuring an adequate public-health system are prerequisites to successfully competing with countries that are currently “talent magnets.” Failing that, countries will be runners-up in the international competition and won’t be able to do anything but watch as their most gifted citizens emigrate and do not return.

As for companies, they need to ensure that they decode what their workers want. This means rethinking their overall people strategies and overhauling their approaches to recruiting, rewarding, developing, retaining, and motivating their workforces. They will have to think globally and find ways of showing appreciation for work that go beyond money. Companies need to ask themselves whether they fully understand these challenges and are prepared for the changes, and whether their existing people strategies and HR operating models will allow them to successfully master these shifts.

Individuals may think the trends are all moving in their favor—but like most things in life, it isn’t that simple. If workers have exactly the skills that are needed in their country of origin or in the country they want to move to, they may indeed be in great shape. But the better the opportunity, the more likely there are to be hundreds or thousands of highly skilled foreigners coming in to compete for the available positions, especially in economies and companies that have laid the right groundwork.

In other words, there is likely to be a much freer flow of talent in the workplace of the future. If they want to be part of it, individuals may not have much choice but to spend parts of their careers in places that aren’t home. To do anything else could be career stifling.

“To me, it’s a must,” says Harald Legros, a 39-year-old Frenchman who has worked in Singapore, Hong Kong, and the UK and is now back in his native country, living in Bordeaux and running an international trade business. “You have to be able to move to the locations where there might be jobs or new business opportunities. If you just say, ‘No, no, I’ll stay in my country forever,’ that might be complicated because in this day and age the world is pretty much open.”

This report is one of BCG’s many publications on people topics and HR trends, which provide companies, economies, leaders, and others with insights into today’s and tomorrow’s people challenges. It also represents a continuation of The Network’s research in the area of international talent mobility. The Network did other studies on this topic in 2006, 2009, and 2011.

For further information on the survey conducted by BCG and The Network (including comprehensive insights into the data), please visit www.globaltalentsurvey.com .

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank The Network’s members for their role in distributing the survey and collecting responses. We also thank the participants who completed the online survey, as well as those who took part in follow-up interviews.

We thank the members of the project team, namely Florian Adolph, Pierre Antebi, Hana Besbes, Jacqueline Betz, Julien Bigot, Pamela Cabral, Meike Decker, Katrin Jaskiewicz, Geraldine Kaiser, Dominik Keupp, June Limberis, Tania Moser, Cleo Race, Samuel Schlunk, Susanne Schrader, Sarah Schröder, and other colleagues from BCG and The Network for research, coordination, and analysis.