What characteristics distinguish Saudi youth from their peers in other countries? How satisfied are Saudi youth with their lives? What are their most important needs? These questions have become increasingly important to Saudi Arabia’s government and business leaders as they pursue initiatives to improve the lives of the kingdom’s young people.

In a recent quantitative and qualitative study of Saudi youth, The Boston Consulting Group, working with ComRes, sought answers. We found that Saudi Arabia’s young adults lead varied lives. Still, the story of one 24-year-old man helps illustrate the plight of his age cohort: This young man, unemployed and single, lives with his family in Jeddah. He told us that he spends his days sleeping, chatting with friends online, and playing or watching soccer matches. He lacks connections that might help him get a job, he says, citing the prevalence of nepotism in hiring. He wants to find a job, get married, and buy a home and car, but he does not know how to make this happen. “If God wills this ambition, it will come true,” he told us.

Stories like this are all too common among Saudi youth today, and their concerns warrant urgent attention. The 13 million Saudi citizens under the age of 30 represent approximately two-thirds of the population, making the kingdom much “younger” than most countries. On average among countries globally, the under-30 youth segment makes up approximately half the population, and in developed countries, that group is slightly more than one-third of the population.

The consequences of having a large youth segment are already evident and likely to intensify. For example, approximately 1.9 million Saudis will enter the workforce over the next ten years, increasing the size of the current workforce by more than one-third. To accommodate this influx of new workers, the country will need to create more jobs in both the public and private sectors, as well as decrease its reliance on foreign workers. As the “youth bulge” moves through the life cycle, the pressure will intensify to improve the education system, create jobs that pay well, provide affordable housing, and offer effective social services.

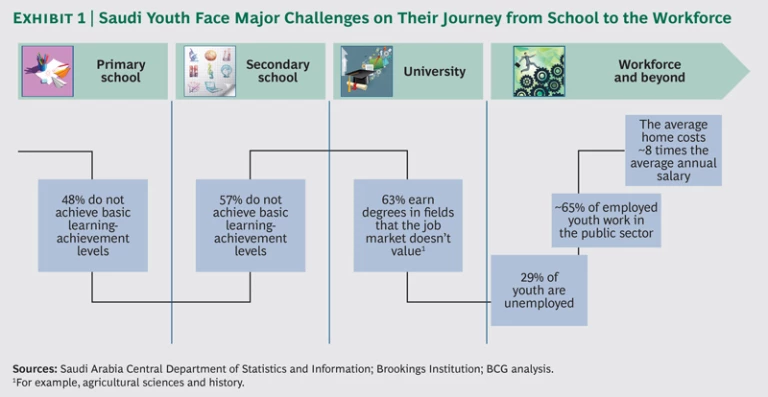

The challenges facing Saudi youth are reflected in data that traces their path from primary school through university and into the job market. (See Exhibit 1.) Forty-eight percent of primary-school students and 57 percent of secondary-school students do not meet basic learning-achievement levels. Sixty-three percent of university students receive degrees in subjects—such as agricultural sciences, education services, and humanities and the arts—that do not provide skills valued by private-sector employers. The absence of valued work skills among young Saudis is reflected in the fact that only 35 percent of those aged 16 to 29 have private-sector jobs. The unemployment rate for this age group is an astounding 29 percent. Furthermore, even those who have jobs struggle to find affordable housing. The average cost of a home is 8 times the average annual salary among all Saudis, compared with, for example, 3.4 times the average salary in the U.S.

Recognizing the challenges reflected in such data, the Saudi government has invested heavily in efforts aimed at improving the lives of the country’s youth. Indeed, the government’s 2014 budget set a record for expenditures focused predominantly on the youth, reaching an estimated investment of 21,000 riyals (approximately $5,600) for each Saudi aged 16 to 29. These investments (excluding infrastructure projects) relate primarily to funding the education system as well as specific intervention programs in education, job creation, housing, and social welfare.

Although the government’s initiatives are beginning to have an impact, they represent just the start of what should be an ambitious and well-coordinated multiyear effort. It is imperative that government policy makers and their partners in the business community who seek to develop nationwide initiatives understand not just the raw data but also the realities facing Saudi youth today.

What Really Matters to Young Saudis?

To see behind the numbers and understand what really matters to Saudi youth, we went directly to them. Meeting with these young people face-to-face, we asked them to describe their lives and concerns.

In January and February 2014, BCG and ComRes conducted interviews with 1,000 Saudis aged 16 to 29. The sample was weighted to represent Saudi youth demographics in terms of gender, age, social grade (a composite of occupation, household possessions, and monthly household income), region, and urban or rural location. To supplement the survey findings, we conducted focus groups with Saudis aged 18 to 29 from Riyadh and Jeddah. We divided the participants into four groups (one all-male and one all-female group for each of the two cities). Each focus group included a balanced selection of university- and nonuniversity-educated students, public- and private-sector employees, and unemployed.

Our analysis of the quantitative findings included measuring the extent to which different factors influence “life satisfaction”—an individual’s subjective perception of his or her well-being. We conducted separate analyses of the sources of life satisfaction for men and women and used a correlated-components regression (CCR) analysis to determine the most important sources of life satisfaction for Saudi youth.

A Generation Shaped by Islam, Family, and the Internet

Saudi youth are strongly influenced by Islam and the importance of family life, and they have integrated digital communication into this traditional lifestyle.

Islam strongly influences identity. When we asked Saudi youth to identify the main influences that shape their identity, 97 percent of respondents cited Islam as either “important” or “very important.” Nationality and ethnicity ranked lower, at 79 percent and 76 percent, respectively. Islam’s strong influence is to be expected, given that the religion is integral to the kingdom’s identity.

Most focus-group participants regard economically strong countries that have maintained their traditional cultures as models for Saudi Arabia’s development. The non-Muslim countries most prominently cited as exemplary are China, Japan, and South Korea. Indeed, some young people said that they do not regard Western countries as role models for Saudi culture. A woman from Riyadh expressed concern about adopting a Western lifestyle: “We don’t want the European cultures where the female leaves her parents’ house to live alone when reaching a certain age.”

Family is still central. Islam’s teachings strongly emphasize the importance of respect for parents and the centrality of the family in one’s life. As a result, the family remains the strongest institution in Saudi culture and has a major influence on expectations and ambitions. In our survey, 98 percent of young Saudis told us that one of their main goals in life is to make their parents proud.

The importance of family is reflected in the extraordinary amount of time young Saudis spend with their relatives. Eighty-six percent of respondents stated that they socialize face-to-face with parents or other relatives every day—a level of interaction that would be remarkable for young adults in many other countries.

Digital communication has been integrated into the traditional lifestyle. Young Saudis have grown up in a world increasingly dominated by the Internet. But they do not seem to regard the digital lifestyle as being in conflict with the traditional lifestyle. Instead, our survey findings suggest that young Saudis are integrating new modes of staying informed and communicating into their traditional lives. Eighty-one percent of survey respondents told us that they visit YouTube at least once a day. Seventy-one percent said the same for Twitter and 67 percent for Facebook.

Twitter appears to be having an especially pervasive influence on Saudis. According to one study, Saudi Arabia has the most Twitter users as a percentage of online users (83 percent). Another study estimated that more than one-third of Saudis are active users of Twitter. The popularity of Twitter accounts relating to Islam illustrates how Saudis have integrated their digital and traditional lives. For example, a BCG analysis found that seven of the ten most-followed personal Twitter accounts in the Gulf region publish content featuring Islamic values.

Gauging Life Satisfaction and Its Sources

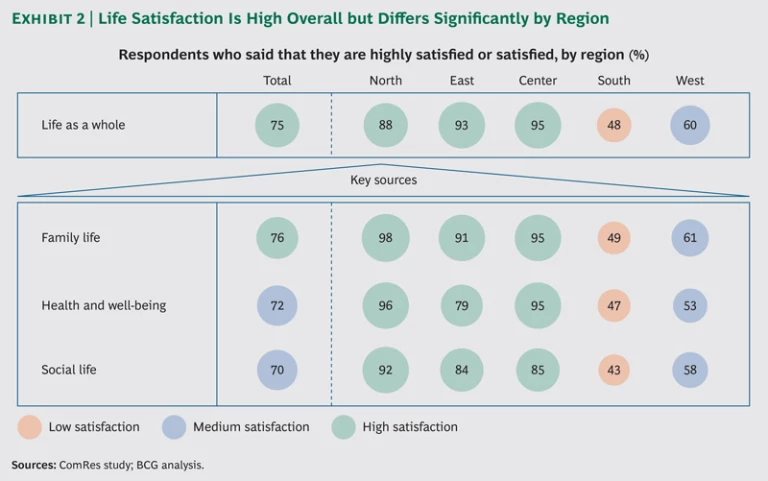

Seventy-five percent of the sample reported satisfaction with life. In terms of specific aspects of life, respondents said that they are most satisfied with family life (76 percent are satisfied or highly satisfied), followed by health and well-being (72 percent), and social life (70 percent). (See Exhibit 2.)

Respondents indicated much lower levels of satisfaction with other aspects of life, such as career opportunities and education. However, the CCR analysis found that satisfaction with family life, social life, and health and well-being were also the best predictors of overall life satisfaction. Satisfaction with family life was the best predictor, followed closely by the other two categories.

We found significant regional differences in life satisfaction: respondents in the southern and western regions reported much lower levels of satisfaction. During the focus group discussions, participants noted that the country’s northern, eastern, and central regions have enjoyed continuous development, which promotes both better opportunities and greater life satisfaction. In contrast, the south and west have lagged behind.

The regional disparity in satisfaction with social life is especially notable. Even in cases where satisfaction levels were high, focus group discussions revealed that many young Saudis are frustrated with the absence of social outlets, making this a critical area for policy makers to address. (See “Helping Saudi Youth Find Outlets for Social Activity.”)

HELPING SAUDI YOUTH FINDS OUTLETS FOR SOCIAL ACTIVITY

Many focus-group participants cited the absence of social outlets and activities outside the home as undermining their satisfaction with social life, a primary source of overall life satisfaction. One young woman told us, “We want places that we can visit with our families. There are no parks. There is nothing for us. We want a place where we can relax without harassment.”

Some young Saudis suggested that participation in volunteer activities would be a valuable social outlet, but they expressed frustration about the lack of available information related to such activities. A young woman explained: “There are no advertisements for voluntary associations. We find out about volunteer activities just a few days before they end.”

To address such concerns, policy makers might encourage traditional and digital media to report regularly on opportunities to participate in charities and other volunteer activities. The government might also consider ways to make it easier to establish volunteer organizations and develop ways for young people to get information about them. A government-sponsored umbrella body—say, a National Association of Community Organizations—might be created with a strong online presence. Such an umbrella body could provide support and one-stop access for people seeking to start or join community organizations.

Young Saudis’ Top Concerns

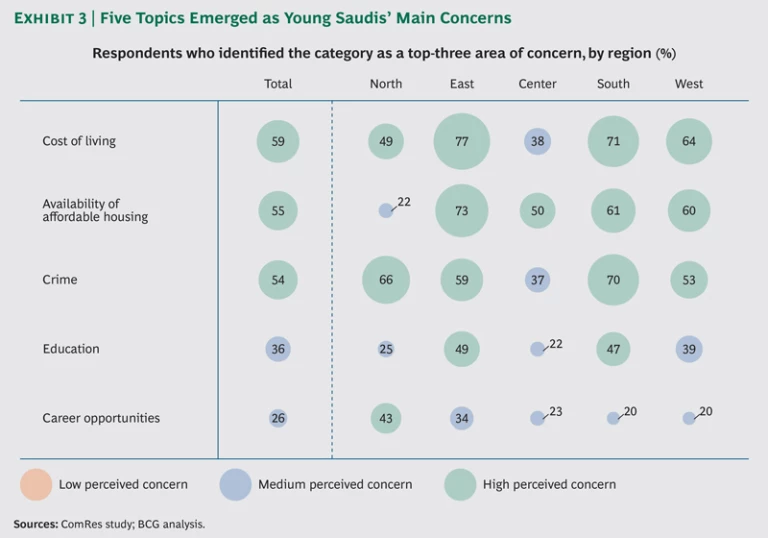

We asked young Saudis to tell us about their primary areas of concern. The percentage of respondents citing an issue as one of their top three concerns was used to identify the five categories of concerns that Saudi youth perceive to be most important. (See Exhibit 3.)

The High Cost of Living. Overall, nearly 60 percent of young Saudis ranked the high cost of living as one of their top three concerns. Regional disparities are quite apparent: respondents from the east and the south were more likely to cite this as a top concern than were those from the center.

In the focus groups, many young Saudis expressed fear that the high cost of living would limit their ability to marry and have children. One focus-group participant cited the disparity between salaries and living expenses: “Currently, salaries are very low, and the cost of living is very high. If a young man earns 3,000 or 4,000 riyals per month, how can he afford the cost of living when he might be spending around 200 or 300 riyals per day?” A university-educated man echoed the concerns of many: “In general, the high cost of living is the reason for all the problems in life. In the past, people used to marry at 21 or 22, but nowadays it’s very difficult to do that. You will find a person 35 years old and still unmarried.”

The Shortage of Affordable Housing. Closely related to concerns about the high cost of living are concerns about the availability of afforable housing. Overall, 55 percent of respondents included the availability of affordable housing among their top three concerns. This is an especially significant concern in the east, where nearly three-quarters of respondents included it in the top three, compared with only about one in five respondents in the north.

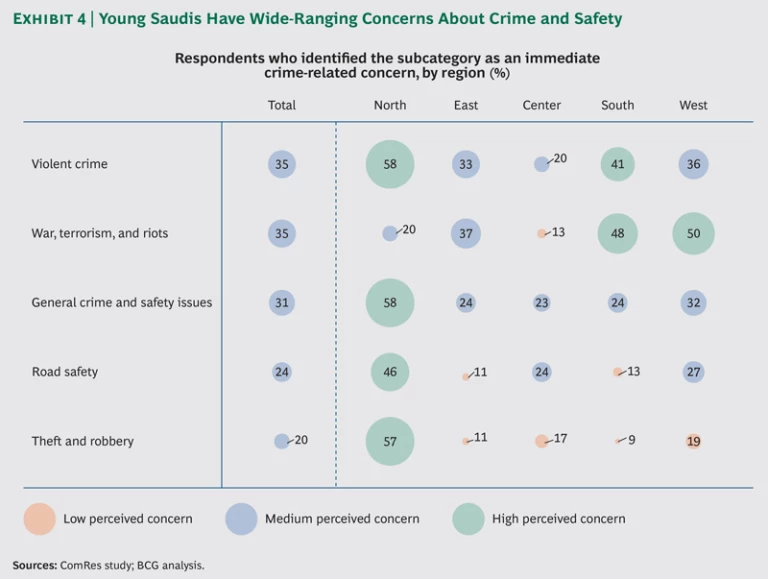

Fear of Crime and Violence. Along with economic issues, many young Saudis are concerned about crime and violence. Nationwide, 54 percent of respondents included crime-related issues among their top three concerns. However, crime appears to be of greater concern in the north and south, where 66 percent and 70 percent, respectively, cited it among their top concerns. In contrast, only 37 percent from the center did so.

A regional breakdown of responses by crime-related topic shows that nearly six in ten respondents from the north expressed concerns about crime in general, violent crime, or theft. Road safety is also a concern for nearly half of respondents from the north. For respondents from the east, south, and west, the main concerns were war, terrorism, and riots. (See Exhibit 4.)

Many focus-group participants said that they had experienced crime firsthand. A young woman echoed the fears of many others: “There is a high rate of unemployment, and there are lots of robberies. You are even afraid that someone will rob your purse while you’re walking around. They even steal your mobile phone from your hand.”

Despite such concerns, Saudi youth do not regard the police as their primary source of protection. When asked with whom they engage if they become aware of any illegal or unethical activity, young Saudis listed the police fourth. Family ranked first, followed by friends and religious leaders.

Shortcomings in the Education System. Overall, about one in three young Saudis cited education as a top-three concern. However, nearly half of respondents from the east and south did so.

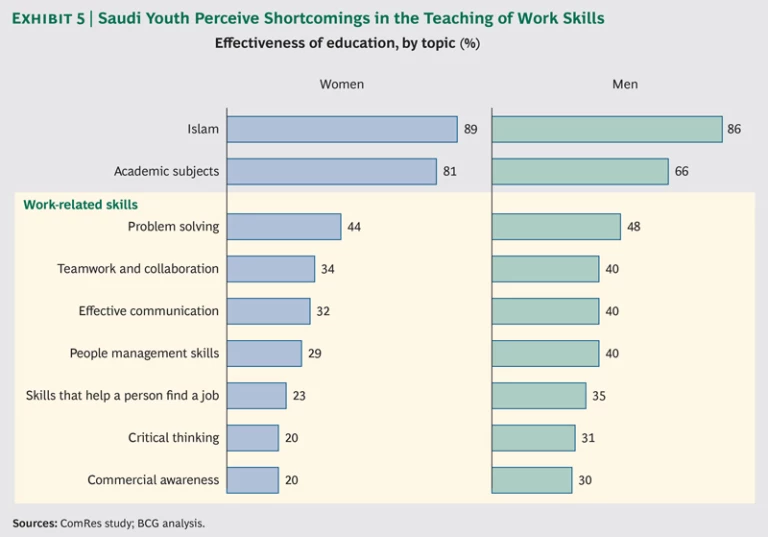

We asked young Saudis about their perception of the effectiveness of the education system. (See Exhibit 5.) Young Saudis consider it effective for teaching them about Islam and basic academic subjects (mathematics, reading, and writing). However, they reported much lower levels of satisfaction with instruction in the “soft” skills—for example, problem solving, teamwork and collaboration, effective communication, and critical thinking—that private-sector employers value. Saudi youth think that despite the great importance of these skills, the education system has not prepared them well, and they lack the skills to succeed in the job market or the workplace.

Focus group participants also voiced concerns about the quality of instruction in computer skills, which are critical in the workplace. A man from Jeddah explained: “We learned a little about computers—but not in depth. And what we learned is nowadays considered outdated.”

The Lack of Career Opportunities. Overall, only about one in four young Saudis cited career opportunities among the top three concerns. Regional differences were significant for this topic as well, as illustrated in Exhibit 3. Forty-three percent of respondents from the north included career opportunities as a top concern, compared with only 23 percent from the center.

Reflecting this regional disparity, one focus-group participant emphasized the limited opportunities for jobs in public-sector departments outside the center, where Riyadh is located: “All the departments are gathered in Riyadh, so everyone has to go there. There are no opportunities in other areas.” Another participant described the frustration in seeking employment: “Every day, I have to search for a job and fill out applications, but it’s hopeless.”

Tailoring Initiatives to Saudi Arabia’s Unique Context

The Saudi government is already pursuing many reforms to address young people’s concerns in the areas that matter most to them. How can this study’s findings be applied to ensure that these reforms achieve the greatest benefits?

In designing and communicating initiatives, policy makers should be guided by two principles: the importance of communicating with all generations—not just the youth—and enabling two-way discussion using digital channels of communication.

Communicate with the entire family, not just the youth. Although reforms are targeted at improving the lives of young Saudis, communication with all generations is essential given the importance of family hierarchies in shaping ambitions and life decisions. Communications about reforms should target multiple generations, using the channel most appropriate for each.

Mobile and online channels should be used to communicate initiatives to young people, whereas traditional print and broadcast media are more appropriate for their parents. Communications through separate channels should be coordinated and should encourage parents and young Saudis to work together to achieve shared ambitions.

Enable two-way discussion using digital channels of communication. Government ministries should use Twitter, Facebook, and instant-messaging services (such as WhatsApp) to encourage a dialogue with young Saudis. The Ministry of Labor and the Ministry of Commerce and Industry, among others, have already adopted this approach by using Twitter and other social media to promote content and respond to inquiries. The Ministry of Commerce and Industry has also created a smartphone app that citizens can use to report violations of commercial laws and regulations (for example, restaurants’ violations of sanitation rules).

To create an early-warning system for problems relating to the delivery of public services, ministries should extend the use of two-way communications for all public concerns and services. The government should ensure that citizens can use social media and instant messaging to contact all public-service agencies—and that those agencies respond to inquiries and provide feedback. Ministry staff should analyze communications from the public and share the analyses with decision makers, eventually responding to citizens with information about the steps being taken to address the issues they have raised.

Putting the Insights into Action

These principles should be applied to the development of initiatives that respond to each of the five main concerns cited by Saudi youth. For each area of concern, we suggest initiatives, as well as a communication strategy, that policy makers and business leaders might pursue.

Alleviating the High Cost of Living. The government might consider sponsoring a “marriage fund” that would provide direct financial support to low-income newlyweds. Such an approach is already being used in the United Arab Emirates. The UAE government provides eligible couples with a grant of AED 70,000 (approximately $19,000) in two annual installments during the first two years of a couple’s marriage. Approximately 12,000 Emiratis have benefited from this program during the past three years. In Saudi Arabia, a similar fund extended to cover the first three years of marriage might require couples periodically to submit proof that they are still married and remain eligible for annual installments. At the same time, the Saudi government might establish a public-private partnership that would provide newlyweds with a discount card they could use for reduced-price purchases of, for example, furniture and groceries at participating retailers.

Public communications might promote the importance of marriage as a religious—rather than financial—union. For example, the UAE’s marriage fund does not cover wedding or dowry expenses, but the government publicly congratulates its young citizens who marry despite very small dowry payments. A similar campaign in Saudi Arabia might bring together traditional religious leaders and entertainers who are popular on YouTube and social media. To reach all generations, a coordinated communication campaign should be launched through traditional and digital channels.

Making Housing More Affordable. Addressing the high price of real estate will be an essential element in reducing housing costs for young families. In our discussions, many young Saudis expressed their frustration at seeing real estate prices rise at the same time that many lots remain unused throughout cities.

Academic and other private-sector experts have proposed redressing this situation by taxing owners of unused real estate. The Ministry of Housing recently announced that it is exploring the possibility of introducing such a measure, and the benefits could be significant. Imposing levies on unused real estate would encourage development and increase the housing supply, thereby reducing prices in the local real-estate market and putting home ownership within the reach of more families. Some landowners will choose to sell parcels rather than develop them. In such cases, the increased supply in the market would drive down the price of undeveloped parcels and ultimately lower housing costs. Money the government collects from such a tax should be allocated explicitly for investment in building affordable housing. Countries in which this land-value-tax approach has been adopted include Australia, Canada, Denmark, Singapore, and the U.S., and the impact has been significant. For example, the city of Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, reduced the number of vacant land parcels by 80 percent after adopting such a tax.

A communication strategy aimed at promoting a land value tax should emphasize the benefits to Saudi society of using vacant real estate for affordable housing. Landowners should be encouraged to recognize the greater good that arises from developing their properties, as well as the economic benefits that they themselves will enjoy. The government should work with business leaders to engage with large real-estate owners about the benefits of promoting development.

Partnering to Prevent Crime and Improve Safety. Young Saudis’ pervasive concerns about crime and safety warrant in-depth examination and research. Policy makers from government ministries should discuss these concerns with young people in meaningful two-way conversations. The objective should be to gain a better understanding of the types of crime that affect Saudi youth and to determine what steps might be taken to address the problem.

The results of these conversations should inform the government’s design of initiatives that will enable citizens and communities to participate in crime prevention. Such initiatives might include making it easier for citizens to report crimes. For example, in the U.S., the Santa Cruz, California, police department offers a smartphone app that allows citizens to report suspicious activity and receive police alerts. Nearly half of the city’s residents have downloaded the app, and they use it to report three to five valid crime tips daily. The Saudi government might also consider creating forums in which local community members and the police can discuss priorities for patrols and other safety measures.

A communication campaign should provide information about safety-related issues through media events and social media, highlighting cases in which citizens helped prevent or solve crimes. It should also promote the police force as a service that works with and for the public.

Helping Young Saudis Learn Employment Skills. The government, in partnership with the private sector, should pursue initiatives aimed at helping young Saudis build the skills they need for private-sector employment and providing access to information about private-sector careers.

The government could, for example, sponsor the development of an online portal that would provide instructional material for career education, including career development guidance and how-to information on writing effective résumés and cover letters. Young people could use the portal to find information that would help them make decisions—on the basis of their career goals—about the next steps in their education, including the courses they should take. They could access information on which jobs are likely to face a shortage of skilled applicants and on career planning. They could also find links to job listings and tools that would help them match their existing skills to a particular career.

All Saudi youth and educators should have free access to the material. Similar online portals have been created in, for example, Australia, France, and New Zealand. OniSep, a French website that offers career information and services, had 35 million visits in 2013. It distributed 15 million free career guides and organized 20 career fairs.

The communication initiatives related to the career portals should enlist successful young businesspeople, entrepreneurs, and educators to promote these websites through social and traditional media. The communication campaign should also be prominently featured on the campuses of secondary schools, colleges, and universities.

Promoting Career Opportunities in the Private Sector. Initiatives that promote private-sector employment should challenge a common assumption: that a public-sector career offers better job security and a more comfortable work environment.

One approach to consider is a large-scale secondment program, in which young public-sector employees with high potential would be encouraged to take two-year assignments at private-sector companies as a prerequisite for promotion. The government might subsidize some of the costs, for example, reimbursing the companies for seconded employees’ salaries during an initial three-month tryout period. A “leadership academy,” jointly funded by private-sector companies and the government, might be established to train seconded employees on professionalism, communication and leadership, and other soft skills. A secondment program would allow participants to gain the experience of private-sector employment while retaining the security of their public-sector jobs. Some participants will decide to seek private-sector employment on a permanent basis while others will return to the public sector, where they will apply their new skills and knowledge.

The Saudi context is unusual in that young people in the kingdom favor public-sector jobs over jobs in the private sector. The converse is true in many other countries, where secondment programs have been used to promote the movement of talented young people to the public sector. Teach For America, which focuses on improving the quality of teaching in low-income areas, is a U.S. example. The program recruits recent university graduates and young professionals for two-year teaching positions at public schools, where they have opportunities to apply their skills, build leadership capabilities, and make an impact through teaching. Many participants choose to remain in the public-school system. As of 2011, more than 7,000 of the 24,000 Teach For America alumni were still teaching, and more than 15,000 were working in education positions or pursuing degrees in education.

The government’s communications on private-sector employment should focus on showing young Saudis that in the private sector they will be able to hone their employment skills and build their résumés—whether or not their long-term goal is a career in the public sector. In media interviews, senior public-sector officials might discuss their preference for employees who have worked in the private sector and developed the valuable skills discussed above.

Shaping the Kingdom’s Future

Policy makers and business leaders seeking to improve the lives of young Saudis face the challenge of designing and communicating initiatives that will drive the greatest impact across a highly diverse population. There is no archetype for Saudi youth. In our survey and discussions, the young people we interviewed revealed many different attributes and expressed a wide range of concerns, many of which differed significantly by region. However, our findings point to ways to maximize the impact of initiatives by targeting the most important sources of life satisfaction and the most prevalent concerns.

In mastering the challenges involved in improving young Saudis’ lives, policy makers and business leaders will build a stronger kingdom without sacrificing its traditional foundations. This difficult task begins with understanding what matters most to Saudi youth.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Andy White and his colleagues at ComRes for their support in conducting the survey of Saudi youth and reporting the findings.

ComRes is a leading market- and opinion-research consultancy providing data-driven insight into corporate reputation, public policy, and communications. In addition to conducting polls for media clients including the BBC and CNN, ComRes teams work as consultants to a range of blue-chip brands, governments, and nonprofit organizations across the world. Coverage includes public and elite audiences across all sectors in all global markets.