The Mobile Internet Takes Off—Everywhere

Each successive technological revolution of the modern age—industrial, informational, digital, and mobile—has played out more rapidly and more uniformly than its predecessors. The current mobile revolution is a supercharged global phenomenon; its impact on individuals, businesses, countries, economies, and societies is already felt just about everywhere. The smartphone, along with the tablet—and a fast-expanding family of wearables and other “smart” devices—have totally transformed the way people around the world live, work, play, connect, and interact.

ABOUT THIS REPORT

The mobile Internet is having an enormous economic and social impact as it continues to grow in size and reach. In Europe and elsewhere, it is an important factor in daily life, as well as a significant generator of economic activity.

To better understand this impact, Google commissioned The Boston Consulting Group to prepare this independent report. The results have been discussed with Google executives, but BCG is responsible for the analysis and conclusions.

Both Google and BCG are pleased to present these findings.

In less than a decade, the mobile Internet revolution has overtaken the digital revolution and is still accelerating. Mobile penetration is increasing, the costs of access and devices are coming down, and more and more people in both developed and developing economies are using the mobile Internet as their first—and often their only—means of going online. To be sure, there remain big issues of infrastructure, remote-area access, data security, and personal privacy, among others, to be addressed. But the combination of consumer demand and market-based innovation has consistently and successfully driven the mobile Internet’s growth, generating enormous economic and social benefits. As we have argued before, for almost everyone on the planet today, regardless of where he or she lives and works, the mobile Internet is already, or soon will be, a life-changing phenomenon. (See Through the Mobile Looking Glass: The Transformative Potential of Mobile Technologies , BCG Focus, April 2013.)

This report, the first in a two-part series, looks at the impact of the mobile Internet in Europe—specifically, in the big economies of the EU5 (Germany, France, the UK, Italy, and Spain)—as well as in 8 other countries. Together, these 13 countries make up 70 percent of global

Exploding Demand for Mobile Access and Services

The numbers tell one part of the story. There are currently almost 7 billion mobile phone subscriptions globally, or one for every person on Earth. In Western Europe, there are 530 million mobile subscriptions, or about 1.33 for every person, of which more than half are for smartphones. Research firm eMarketer expects that in 2017, seven of the top ten countries for smartphone penetration will be in Europe (the U.S. will rank 11), and in three European nations (Norway, Demark, and Finland), smartphone penetration will exceed 90 percent.

Several factors are fueling this growth, including greater access, increasingly sophisticated mobile-device functionality, fast-rising device sales, an ever-increasing range of devices and device types, and sharply falling prices. Another factor is more reliable data connections that enable increasingly data-intensive activities. Some 60 percent of the world’s population is covered by 3G connectivity—the EU has 90 percent 3G coverage—and large swaths of territory are covered by 4G service.

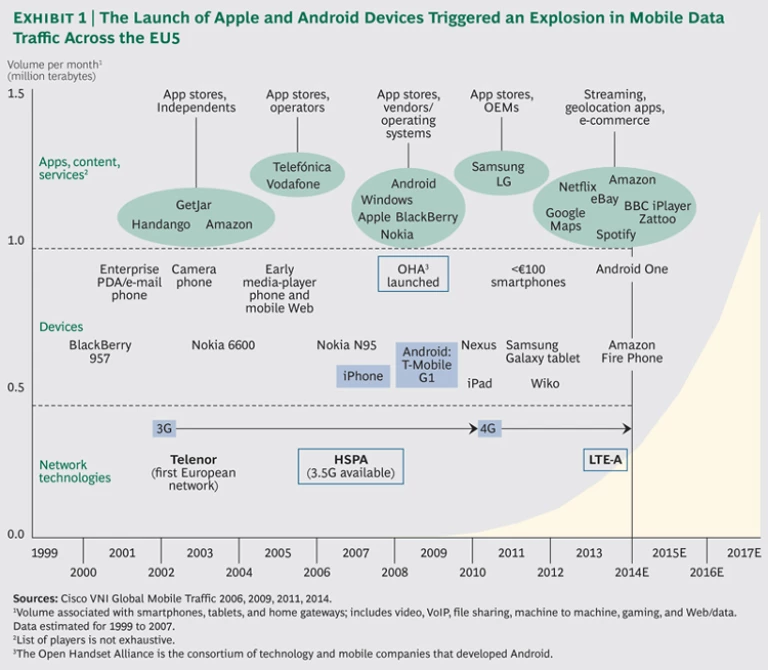

While much has been written on the challenges facing mobile technologies in Europe, consumer demand remains strong. (See “ Delivering Digital Infrastructure ,” BCG article, April 2014.) The volume of mobile Internet data traffic will continue to expand, driven primarily by increased demand for streaming of video and music content on mobile Internet devices. In Western Europe, demand for such services will drive data traffic up sixfold by 2017, from 187,000 terabytes to 1.1 million terabytes a month, supported by more 4G networks coming online and existing operators increasing their speed, coverage, and capacity. (See Exhibit 1.)

More Capabilities for the User

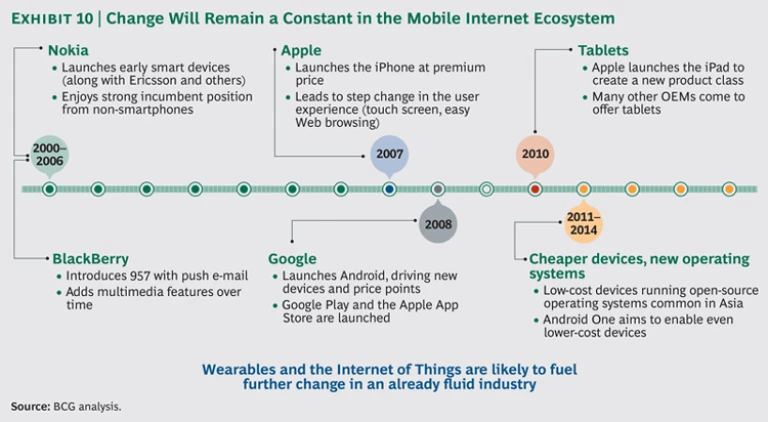

As the mobile revolution has gathered steam, intensifying competition in operating systems and technology has led to more and more innovations in smart-device functionality. Nokia and Ericsson (both European companies) launched the first smart devices with multimedia features in 2000. BlackBerry developed major advances between 2001 and 2007 with such innovations as push e-mail and encryption. The launch of Apple’s iOS and Google’s Android operating system led to a step change in the user experience with the widescale adoption of the touch screen and easy-to-use, full-featured mobile Web browsing, and the rise of third-party app ecosystems.

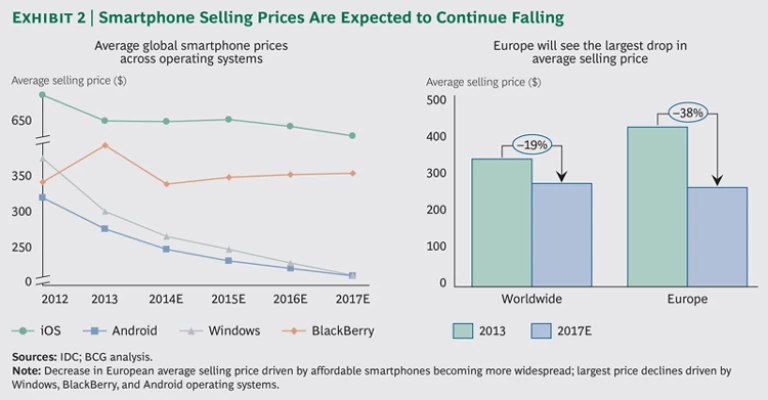

Competition among operating systems and their app ecosystems has also triggered an explosion in device development and sales, as well as in global mobile data traffic. In the EU, smartphones have rapidly come to dominate the mobile phone market as competition provides consumers and businesses alike with more choice, cheaper devices, and new products. Average smartphone selling prices fell 25 percent worldwide between 2011 and 2013 and are expected to drop a further 19 percent by 2017. In Europe, average selling prices are projected to fall even faster—by nearly 38 percent in 2017—for a variety of reasons, including market saturation and prolonged upgrade cycles. (See Exhibit 2.) In France, for example, Wiko devices (launched in 2012) sell for about €70 and captured nearly 7 percent of sales in 2013. Wiko expanded into the UK market in 2014.

SPOTIFY SOUNDTRACKS YOUR LIFE

Launched in Sweden in 2008, Spotify has become a highly popular service and one of the Internet’s household names. The company uses digital and mobile technology combined with a new-to-the-industry business model to give users access to whatever music they want to listen to, whenever they want to listen, wherever they are. Users can stream or download from a library comprising some 20 million songs.

Spotify offers both a free, ad-supported service that gives users limited access to songs and a premium version that lets users download songs and playlists. It provides access via the Web and multiple mobile devices, including those operating iOS, Android, and Windows. Users build playlists tailored to their tastes or to accompany different tasks or activities, which they can listen to at home or in the office and while commuting, shopping, working out, or traveling. They can share songs and playlists through social media such as Facebook and Twitter.

Spotify is available in 58 nations. It was one of the early pioneers of legal music downloading and sharing, with a business model that provides users with access, choice, and convenience at low cost, while also ensuring that songwriters and rights owners receive compensation.

Spotify reached the 10 million user mark in 2010. Its user base doubled by 2012 and doubled again by 2014, to 40 million. The company has paid more than $2 billion in royalties. It had revenues of $577 million in 2012, and $250 million in new funding in 2013 gave it an implied valuation of some $4 billion.

Choice and new products abound. There are more than 18,000 Android mobile-device models currently in circulation, manufactured by a host of third-party OEMs. Global tablet sales will surpass 260 million units in 2014, including 72 million in Europe. TVs are increasingly becoming connected devices that can run apps and perform computing functions as well as broadcast programming. Wearables—smart watches, connected glasses, and fitness monitors (so far)—are a new product category, and market growth and size projections vary. IDC predicts that total wearable shipments will grow from 19 million units in 2014 to 128 million in 2018. Smartphone technology is being built into more and more automobiles.

A Revolution in Behavior

From shopping to sharing to socializing, the mobile experience is a whole new universe of connectivity that’s local (it’s always where you are), personal (tailored to your needs and preferences), social (all your friends are there as well)—and it’s always on. (See “Spotify Soundtracks Your Life.”) Continuous access to information, communication, friends, and entertainment—among myriad other things—is changing the way billions of people go about their daily lives.

Sharing photos and videos on the move is now commonplace, as are tweeting, pinning, and posting. Of Facebook’s 829 million active daily users in June 2014, 654 million (almost 80 percent) were mobile users. Much has been made of the role of smartphones in social uprisings and the response to natural disasters. We regularly watch images on the evening news shot not on video cameras but on smartphones.

Travelers today use their phones to board planes, unlock hotel rooms, monitor devices at home (temperature settings, for example), and check in via live video with their families. Mobile payments are common in many economies; mobile apps are transforming banking. The lines between traditional retail, e-commerce, and m-commerce have blurred almost to the point of indistinction in some markets, as consumers research online, offline, and on the go and buy wherever and however they find the best selection, service, and deals. Moreover, mobile technologies and apps provide a bespoke service to countless subsegments of consumers with highly particular needs. (See “Providing the Disabled with Accessibility Information While On the Go.”)

PROVIDING THE DISABLED WITH ACCESSIBILITY INFORMATION WHILE ON THE GO

Launched in Germany in 2010 by Raul Krauthausen, Wheelmap provides accessibility information to wheelchair-bound people worldwide. The wheelmap.org website or mobile app reads a user’s location and provides a map showing area restaurants, restrooms, schools, churches, and other destinations rated according to their wheelchair accessibility. Ratings are based on data provided by the users themselves—anyone can sign up to contribute. A green flag represents ready accessibility, yellow means partial accessibility, and red signals that the destination is not wheelchair accessible.

Wheelmap was always intended for mobile use. As the company’s Andi Weiland puts it, “The potential to have this tool available whilst out and about is what our users really appreciate. People no longer have to plan their day in advance, or from a laptop, before they leave the house.”

The Wheelmap app has more than 470,000 crowd-sourced data entries and 35,000 monthly users. It is available in 22 languages and has spawned several copycats.

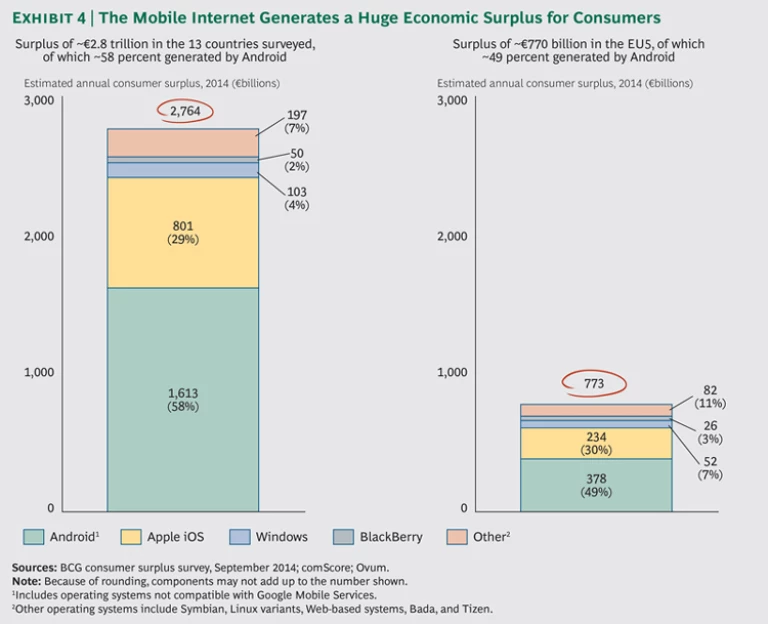

Consumers realize an enormous benefit from all this activity, which can be quantified using an economic concept called consumer surplus—that is, the perceived value that consumers themselves believe they receive, over and above what they pay for devices, apps, services, and access. In the EU5 alone, the benefit accruing to consumers is about €770 billion ($1 trillion) a year. The mobile Internet’s total consumer surplus across the 13 countries surveyed is approximately €2.8 trillion ($3.5 trillion) a year.

Consumer surplus and the other benefits of the mobile Internet are only set to increase—exponentially. An entire generation of 18- to 34-year-olds, a larger group than the baby boomers, already accesses the Internet primarily through their mobile devices. A 2013 survey by Telefónica found that 79 percent of so-called Millennials in Western Europe and 60 percent of those in Eastern Europe own a smartphone. Smartphone penetration among 16- to 24-year-olds in the UK is 88 percent, compared with 65 percent for other age groups. Young users spend on average 2.5 times more time on their smartphones every day than the rest of the UK’s adult population.

Businesses Are Benefiting, Too

The mobile Internet is creating entirely new businesses as well as transforming traditional companies. A technology entrepreneur in Europe today is more likely to be building a business around a mobile application than a website. All kinds of businesses are using mobile technologies to improve operations, cut costs, and reach new markets and customers. The digital economy is flourishing on mobile devices as consumers access and buy apps, music, videos, books, magazines, and other content anytime from anywhere and receive many purchases instantly. They can also buy physical goods on the go using dedicated retailer apps from brick-and-mortar stores such as Tesco, IKEA, and Media Markt, or from online shopping platforms such as Amazon, eBay, and Net-a-Porter.

The app economy is flourishing. There have been more than 200 billion cumulative downloads from the various app stores since 2008. The rate of growth is mind-boggling: more than 100 billion downloads took place in 2013 alone, of which around 20 billion were in the EU.

Payment apps are increasingly popular, and some businesses are cutting out the cash register altogether (DASH, GoCardless, Uber, and Hailo, for example). There are more mobile bank accounts in Kenya than in the UK, but banks in Europe (as in other developed markets) are using mobile apps to transform the banking experience for consumers (you can deposit a check by taking a picture)—and winning plaudits from their customers in the process.

Retailers are embracing m-commerce. France’s Groupe Casino employs near-field communication (NFC) tags on shelves to help visually impaired customers download product information to their phones. It also uses NFC technology to help all customers track costs and speed up checkout. UK retailer John Lewis reports that more than half its online traffic comes from smartphones and tablets. The company’s mobile app topped a 2014 UK user poll of the best mobile shopping experiences, outpacing Amazon, among others.

Mobile commerce in the EU5 reached €23 billion in 2013 (up 76 percent from 2012) and accounts for 13 percent of all e-commerce. Nearly two-thirds of EU5 e-commerce purchases occur on tablets; the analogous figure for the U.S. is about 50 percent.

It’s not just a retail phenomenon, either. All kinds of businesses are finding innovative ways to put mobile devices and technologies to work. According to one survey in the U.S., more than 85 percent of B2B customers access content on their mobile devices. Another survey found that 56 percent of B2B customers read reviews, 55 percent access product information, and 50 percent compare features using mobile devices. Mobile commerce accounts for 3 to 5 percent of B2B sales, and mobile drives 7 to 10 percent of B2B traffic for tasks such as search. These numbers are bound to grow as more B2B users apply the lessons of the B2C marketplace to their businesses.

The Impact of the Mobile Economy

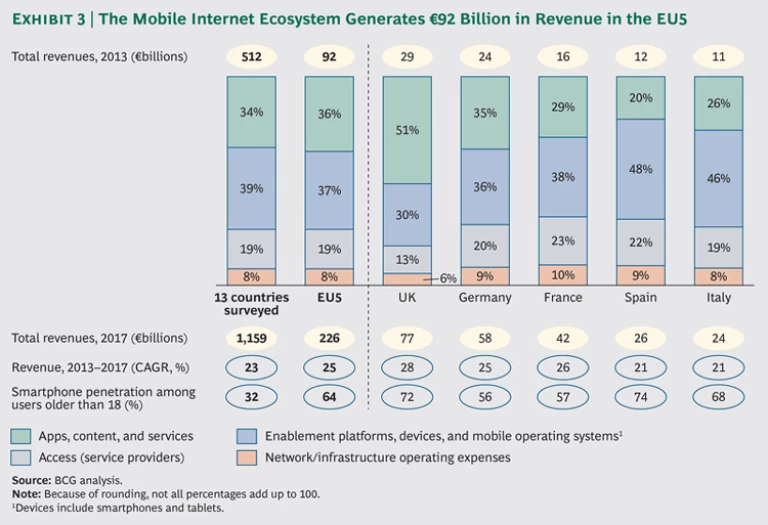

In the EU5, the mobile economy generated about €90 billion ($120 billion) in revenue in 2013, and it is responsible for approximately half a million jobs, of which about half are physically in EU5 countries. In the 13 countries surveyed for this report, the mobile Internet is already generating some €512 billion ($682 billion) in revenues annually—the equivalent of almost €585 ($780) for every adult in the surveyed countries. The mobile Internet economy employs approximately 3 million people in those countries.

The mobile Internet attracts substantial investment. For example, leading app-store operators paid developers over $15 billion between June 2013 and July 2014. Major companies, from telcos (such as Telefónica, Deutsche Telekom, and Orange) to hardware, software, and semiconductor manufacturers (such as Ericsson, ARM, and SAP) to content providers (such as Spotify, Pearson, and Yudu) invest billions of euros in R&D and capital expenditures, and countless start-ups are also attracting investments, innovating, and launching new products.

Mobile has only begun to touch the surface of multiple industries that have an enormous impact on GDP—health care, for example, where wearable devices are beginning to monitor data related to consumers’ health and well-being. Travel and transport are going mobile, and the opportunities to expand educational opportunity are endless. These are only a few of the countless potential applications.

As the volume of mobile traffic and activity relentlessly expands, the complexity of the industry that transports and delivers millions of terabytes of information globally every day increases as well. The industry is evolving rapidly. Competition within and among ecosystems is fueling innovation, diversity, and choice for end users.

Competition Drives Mobile Internet Growth

In Europe as elsewhere, mobile usage is growing fast as consumers shift from fixed to mobile devices for online media consumption, commerce, information seeking, and social networking, among other activities. Increasing mobile access everywhere is leading to new uses of the Internet—in fields from banking to education and from health care to the delivery of public services—further propelling its growth. Companies, governments, schools, hospitals, not-for-profits, and NGOs, among other organizations, increasingly realize that they need to interact with their stakeholders not just online but via smartphones and tablets. It is only a matter of time (and perhaps not much more time) before the Internet becomes a mostly mobile phenomenon.

Mobile Internet Revenues Are Growing Fast

The revenues generated by the mobile Internet ecosystem are a substantial contributor to global GDP as well—€512 billion ($682 billion) across the 13 countries that account for 70 percent of global GDP. The mobile Internet is driving significant and growing revenues across Europe—€90 billion ($120 billion) in the EU5 in 2013. Put another way, adult Europeans in these countries each spend €555 a year on phones, tablets, data plans, apps, digital content, and m-commerce. (See Exhibit 3.)

By 2017, EU5 mobile Internet revenues will have more than doubled to about €230 billion ($300 billion)—an annual growth rate of 25 percent, which is comparable to the growth of these revenues in both China and the U.S. The single largest contributor to this growth will be the apps, content, and services component of the ecosystem, driven by the rapid expansion of mobile shopping and advertising. By 2017, we estimate that mobile Internet revenues will have grown to €1.16 trillion ($1.55 trillion) across the 13 countries surveyed, an annual increase of 23 percent.

The Mobile Internet Creates Jobs, Too

Revenues are one part of the picture. The mobile Internet is also a major job-growth engine. We estimate that the total impact for the EU5 is about half a million jobs, of which half are physically located in EU5 countries. These jobs are primarily in device sales, distribution, and production, as well as in apps, content and services, service providers, and network infrastructure.

Across the 13 countries surveyed, we estimate that approximately 3 million people were employed by the mobile Internet economy in 2013. While many of these jobs are in Asia, where the manufacturing of mobile devices is centered, the rapid growth in device sales generates retail jobs throughout the U.S. and Europe, as well as in other regions. Network and infrastructure installation and maintenance take place worldwide. Enablement platform and mobile operating system-related jobs are based primarily in the U.S. and Europe. These jobs tend to be created in countries with well-educated and skilled workforces, and their numbers will grow as activity in these and other segments of the ecosystem expands. A significant proportion of these positions are entrepreneurial and situated in small enterprises—young (or maybe not so young) men and women hoping to impress users with the next big thing and hiring others when they do.

With revenues from the mobile Internet forecast to more than double by 2017, there will be a related—and significant, if not proportional—increase in the number of jobs generated. Some of these positions will replace jobs currently found in the broader Internet ecosystem—for example, positions related to feature phones, particularly in developing economies. We expect a substantial number of new and incremental jobs to be created, too, as the demand for apps, content, and services rises disproportionately with the increase in the installed user base. The advent of new apps that automate and enhance existing activities, in fields such as finance, health care, and education, will help fuel this growth. Many of these jobs will require a high level of technical skill and creativity, and it will be important for governments to support appropriate education, training, and mobility programs to ensure that their workforces are in a position to take advantage of the opportunities that will be generated by the mobile Internet.

Challenges in Europe

We have argued elsewhere for EU policy makers to help fuel the growth of Europe’s digital economy. (See “ Europe’s Digital Economy Needs a New Foundation ,” BCG article, October 2013.) Many of the same principles apply to the EU’s mobile Internet economy, particularly with respect to advancing the goal of a single digital market through the EU’s Digital Agenda for Europe, addressing Europe’s inefficient and fragmented system of spectrum allocation, and furthering the development of a vibrant digital-services sector.

Europe was an early adopter of faster data connections. Some 90 percent of the population is currently covered by 3G connections, 3G devices account for more than half of all devices, and the EU has the largest number of 3G SIM cards per capita globally. Data is also relatively inexpensive. Fierce competition has driven down prices to the point where the monthly cost of a 5 gigabyte mobile broadband subscription is €18 in the UK, €19 in France, €23 in Germany, €9 in Italy, and €39 in Spain—compared with the equivalent of €42 in the U.S. The European Parliament has voted to abolish roaming fees by December 2015, but the Council of the European Union still needs to approve this policy.

That said, investments in mobile infrastructure equipment have fallen by some two-thirds since 2004, as investment in long-term evolution (LTE) technologies have not matched the heavy spending on 3G networks. European LTE spending, on a per-subscriber basis, is half that of the U.S. and Japan. In the EU, 4G connections make up only 3 percent of the total, compared with about 25 percent in North America. While there are significant gains to be had from 4G, EU carriers need greater economies of scale and scope to invest in and integrate EU-wide systems.

One result of this lack of investment is that data connections are slower in Europe than elsewhere. The average mobile connection speed in Western Europe was 1.5 megabits per second (Mbps) in 2012, compared with 14.7 Mbps in South Korea, 10.7 Mbps in Japan, and 2.6 Mbps in North America. This data-speed gap is set to widen: the average connection speed in Western Europe will reach 7.0 Mbps in 2017, only half the speed of North America’s 14.4 Mbps.

Another result is that European carriers lag those in other markets in their ability to generate revenue growth from mobile broadband consumption. Average revenue per user in the EU has fallen more than 5 percent in the last six years. Part of the problem is consumption: EU users consume only 415 megabytes (MB) of data per month, compared with 810 MB, on average, for U.S. users. This creates something of a conundrum: the cost per unit of data remains high for carriers, and the speed of connections (3G rather than 4G) stays low for customers. Part of the answer lies in enacting policies that provide incentives for infrastructure investment and building economies of scale for infrastructure layers such as telcos. (See “ Reforming Europe’s Telecom Regulation ,” BCG article, July 2013.)

One of the biggest constraints on more mobile data usage is the availability, allocation, and use of the mobile spectrum—the bands of radio waves over which data and voice communications (as well as other over-the-air media) travel. Lack of harmonization at the regional and international levels—meaning, for example, that the same operator’s 3G network operates on different bands of spectrum in different countries or in different regions of the same country—leads to significant inefficiencies and higher costs. The GSMA (Groupe Speciale Mobile Association) has estimated that harmonizing data spectra across Europe would generate €119 billion in incremental GDP between 2013 and 2020 and create some 156,000 new jobs. Delaying harmonization until 2017 would reduce the impact on GDP by €16 billion and the number of new jobs by 67,000. In the meantime, some European telcos are coming up with innovative alternative solutions. (See “Crowdsourcing Wi-Fi Signals into Community Hotspots.”)

CROWDSOURCING WI-FI SIGNALS INTO COMMUNITY HOTSPOTS

Launched in 2006, Spain’s Fon uses an innovative crowdsourcing approach to expand the number of Wi-Fi “hotspot” connections available to mobile users. In the process, it addresses two issues. It helps users with devices such as Wi-Fi-only tablets stay connected on the go, and it reduces data traffic strain on telcos’ mobile networks. The company has hotspots in 1,000 cities in 200 countries. It offers more than 13 million hotspots, which it plans to increase to 35 million by 2016.

The cleverness of Fon’s model lies in its crowdsourcing simplicity. Users make their home or business Wi-Fi signal available to outsiders; in return, they get free access to Fon’s other Wi-Fi hotspots. Sharing does not compromise privacy or speed. To join, users either buy a Fon router or join one of Fon’s 11 national telco partners, such as BT in the UK and KPN in the Netherlands. Users who don’t want to share their Wi-Fi connections can pay to access Fon.

Fon hotspots are available throughout Europe and the U.S. and in most of Latin America, Asia, and Australia. In 2014, Fon launched a business service that allows small and medium-size companies that share their Wi-Fi signals to receive customer use and location data, which, in turn, allows these companies to provide users with customized promotions.

There are wider social benefits to better mobile connectivity as well, in health, education, and government services, among other fields. Mobile health solutions can influence patient behavior, enable remote treatment of chronic illnesses, help improve diagnosis, and make health care more efficient. There are already multiple apps on the market that help patients with such diseases as diabetes and hypertension; other apps are designed to bring new capabilities to doctors, hospitals, and other health-care providers. Better m-health could benefit 185 million EU patients and cut nearly €100 billion in health care costs, according to the GSMA. In the dynamic market for online learning, most operators of massive open online courses, or MOOCs, offer mobile apps enabling students to engage in courses and coursework wherever and whenever they choose. Forward-thinking municipal governments are using mobile technology to reduce energy consumption, cut pollution levels, and improve public safety. Madrid’s integrated traffic-management system has reduced emergency services response times by 25 percent.

The App Economy Soars

Mobile apps—the software programs that perform designated functions on a mobile device—may be the fastest growth story in recent history. Originally designed primarily to facilitate productivity and information retrieval (mobile calendars and e-mail, for example), mobile apps quickly expanded into numerous other fields, including gaming, navigation, health and fitness, media consumption, communication, and commerce, to name a few. Europe has some of the largest and most successful mobile game developers in the world, including Rovio, King, Mind Candy, Supercell, Mojang (Minecraft), and Wooga. UK-based Mind Candy launched Moshi Monsters in 2008 and now has more than 80 million registered users across 150 countries. Germany’s Wooga has more than 50 million active monthly users across its series of hit games that include Diamond Dash, Jelly Splash, and Pearl’s Peril.

Apps are coded by developers, many of whom are app entrepreneurs, and sold through app distribution platforms such as the Apple App Store, Google Play, the Windows Store, Amazon Appstore, and BlackBerry World. App developers have made 1.3 million apps available through both the App Store and Google Play, some 255,000 through the Windows Store, 240,000 through Amazon, and 130,000 through BlackBerry World. In 2013 alone, apps were downloaded 102 billion times globally (of which 9.2 billion downloads were of paid apps), a 60 percent increase over 2012. Downloads are forecast to rise to 269 billion (15 billion paid) by 2017. Although many apps are given away free of charge, app revenues in our 13 country sample reached $26 billion in 2013 and will almost triple to $76 billion in 2017.

Despite—or perhaps because of—this extraordinary growth, there are anecdotal signs that the app industry may be starting to mature. For example, the average number of apps downloaded across all devices per month in the UK fell from 2.32 apps per user in 2013 to 1.82 apps per user in 2014.

App Developers: Show Us the Money!

Even with the astronomical growth in the app economy, many app developers still struggle to monetize their endeavors. The vast majority of app downloads continue to cost nothing: nine out of ten downloads in 2013 were free; eight of the ten most-used apps globally are given away.

Developers are faced with a challenging business environment: a hit-driven market, in which relatively few apps gain critical mass, and low barriers to entry, with copycats and knockoffs of successful apps an all too common phenomenon. As a result, many independent developers earn little.

Since apps generate revenue through up-front download fees, ads, and “in-app” purchases (of extra content like bonus game levels), a developer’s income typically depends on a large number of downloads and regular use of one or more of its apps. But only the top 200 to 300 apps are seen and downloaded by substantial numbers of users. Large developers backed with deep pockets can tilt the playing field by paying to advertise their apps through a variety of channels.

Adding salt to the wound, some developers “copycat” apps, undermining innovation. It took more than a year for one developer to craft a popular puzzle called Threes!; copycats hit the market only 21 days after its launch. In addition, some unscrupulous developers seek to game the ranking algorithms in order to move up on lists of consumer preferences, despite the best efforts of app stores to maintain quality control.

More than half of all developers earn less than $500 a month per app, and the top 1.6 percent of developers earn more than the other 98.4 percent combined.

Developers Seek to Adapt

In the face of these and other challenges, developers are using a variety of strategies to adapt. For example, some are choosing to specialize, producing niche apps in narrow fields (wedding planning, for example) in which they can charge a premium. While the market is smaller, the competition, especially from free alternatives and copycats, can be less intense—at least for now. On average, developers that focus on “mass-market reach” apps earn half as much as developers that build niche apps for consumers willing to pay for the service.

One area of growth is apps for business. Productivity apps are increasingly in demand, and companies are more likely than individuals to spend money on regular maintenance and updates.

Other developers are focusing on emerging areas of the mobile ecosystem. The so-called Internet of Things (IoT)—machines and devices that communicate directly with other machines and devices—is widely expected to become a major source of digital growth, but the initial winners have been big manufacturers, such as Adidas in health and fitness, rather than independents.

App developers, along with others throughout the mobile ecosystem, also face continuing challenges in such areas as security. Threats are on the rise. Reports of mobile malware rose 167 percent in the 12 months ending in June 2014, with some 15 million mobile devices infected in 2014, up from 11.3 million in 2013. Just as Windows has been the target of most malware aimed at desktop operating systems, the most popular mobile operating systems are targeted because they are where the largest number of users can be found. Fragmented open-source code can be more vulnerable to malware, and secondary app stores are key targets. One response from entrepreneurial developers has been new apps designed to secure phones (such as MobileIron, Samsung Knox, and XenMobile), but these usually rely on installation and updating by users rather than by device manufacturers.

Building sustainable revenue models for independent developers continues to be a big challenge. We expect developers to focus on two primary approaches.

Advertising-Supported and “Freemium” Revenue Models. More and more advertiser spending will shift to mobile over time, as consumer usage continues to increase and targeting technology improves. Global mobile advertising revenues will reach $18 billion in 2014, up from $13.1 billion in 2013, and this growth will continue until 2017, when spending will exceed $41 billion. Europe accounts for about 17 percent of global mobile advertising spending, according to the Interactive Advertising Bureau.

About 90 percent of Apple’s global App Store revenue in 2013 was attributable to freemium apps—which are free to download but can ultimately lead to in-app purchases—up from 77 percent in 2012. Freemium apps have demonstrated their profitability, but some have also come under criticism for allowing users to incur unexpected costs, such as through any in-app purchases that they wind up making.

Building Apps for Others. One area where developers are demonstrating success is building apps for other businesses. Some 70 percent of developers say they are profitable when doing contract work for others. Demand for app development is growing as industrial applications increase. Companies often do not have their own in-house developer talent and are willing to pay for functionality that can increase sales and profits.

For example, developers are finding new opportunities to connect, monitor, and control IoT devices remotely. Some 25 billion new devices (including cars, heating and air-conditioning units, lighting systems, farm equipment, wearables, and security systems) will come online from 2015 to 2020, doubling the current number. (See “The Next Big Thing: The Internet of Things.”)

THE NEXT BIG THING: THE INTERNET OF THINGS

The long anticipated, much maligned, Internet-enabled fridge is actually a reality. The Internet of Things brings inanimate objects online and enables them to communicate their internal state, among other types of information, to humans and other “things” through the Internet. Many of these objects are things on the move, such as cars and aircraft; they use mobile technologies, sensors, and software to stay connected. Once an object can represent itself digitally, it can be controlled remotely.

The number of connected devices is growing fast. There were 500 million of them in 2003 and 12.5 billion in 2010; these numbers are expected to rise to 25 billion in 2015 and to 50 billion in 2020 as costs, especially for sensors, fall. A sensor that cost €50 in 2009 sold for €15 in 2013.

The potential applications are endless. A few examples: airplanes that warn of component wear and potential failure; cars that automatically schedule their own maintenance; buildings with HVAC systems that can be controlled remotely; buses that update their performance against schedule in real time; tracking devices in farm animals that monitor food intake, temperature, and movements. In almost every sector, the Internet of Things will vastly lower costs, improve safety, and heighten efficiency for consumers and businesses alike.

Already companies such as Italy’s Solair Corporate are designing company-specific apps for the Internet of Things. Using Solair technology, manufacturers can monitor machine performance to optimize production, streamline maintenance plans, identify faults early, and reduce costs. The company provides an automated app platform that helps connect and automate machines and activities in such areas as fleet management, maintenance, and health and safety in six markets: retail, industrial machinery, smart buildings, energy, transportation, and health care.

A big area of potential growth is machine-to-machine (M2M) communication—networked devices of all kinds, in such industries as automotive, consumer goods, and utilities, that exchange information and perform functions without the physical assistance of humans. An aircraft engine that monitors and reports operating data in-flight is one example; buses and trucks that continually report their location, speed, and other information is another. Research organization IDATE expects the M2M market to reach €40 billion by 2017, with Europe as the biggest geographic market in terms of revenue. The EU had 52 million M2M connections in 2012 (about a quarter of the global total), and these are expected to grow to 295 million in 2017 (30 percent of the global total).

Consumers Win Big

The revenue numbers measured in the previous chapter are large. But they pale in comparison with what must be considered the real value of the mobile Internet: what all this activity is worth to the end user. Consumers, especially European consumers, are the big winners here. And the margin of victory runs into the trillions of euros.

Europe has come under criticism for “missing out” on the digital and mobile boom; with a few exceptions, this story goes, most of the big names in these industries—Apple, Google, Facebook, Alibaba, and Samsung, among others—have emerged from the U.S. and Asia. Putting aside whether this story is true, it clearly hasn’t stopped European consumers, along with consumers in the rest of the world, from making full use of the benefits the mobile Internet offers.

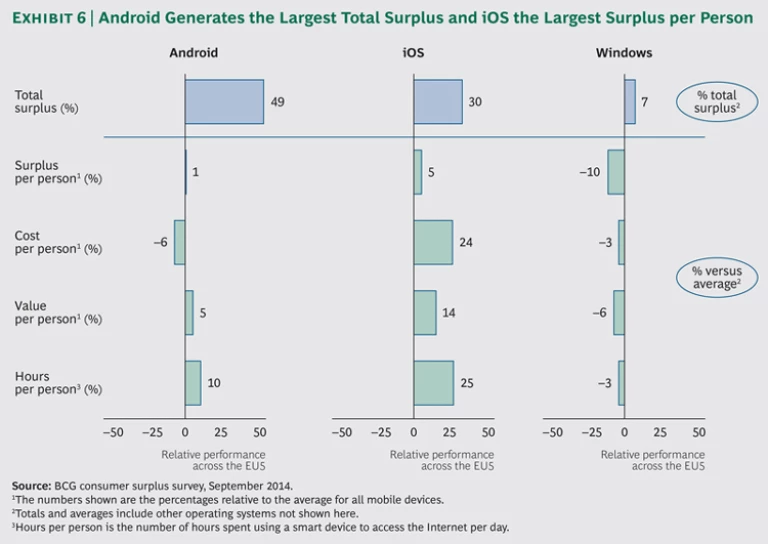

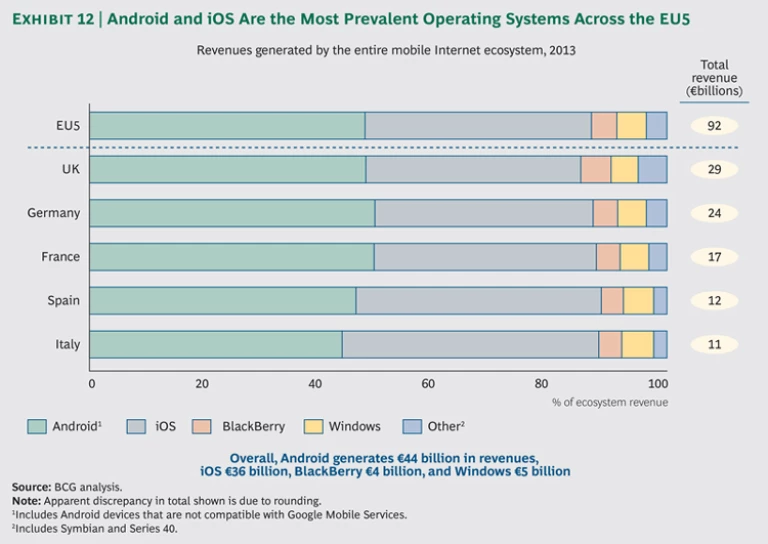

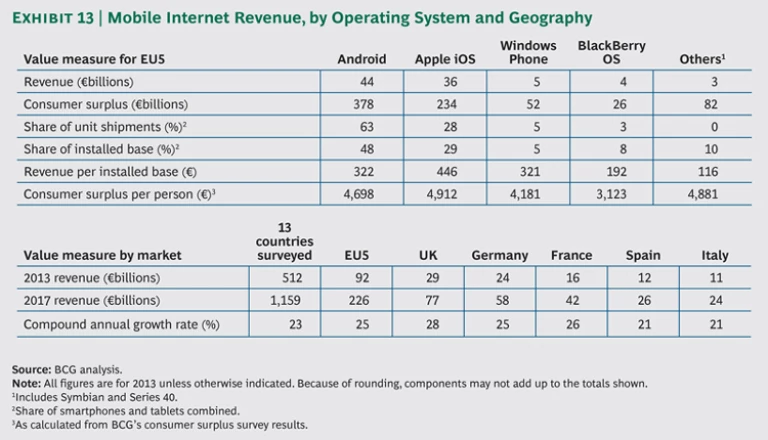

The consumer surplus from the mobile Internet in the EU5 alone is about €770 billion ($1 trillion) per year. The mobile Internet’s total annual consumer surplus across the 13 countries surveyed is approximately €2.8 trillion ($3.5 trillion). In the EU5, Android generates almost half of this surplus (€378 billion), iOS produces 30 percent (€234 billion), and the rest is divided among the other mobile operating systems. Across the 13 countries in our survey, Android is responsible for 58 percent of the surplus and Apple, 29 percent, reflecting Android’s popularity in most developing markets. (See Exhibit 4.)

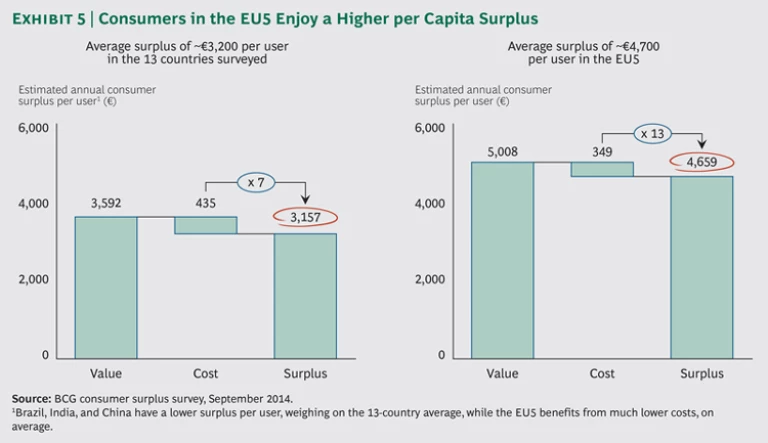

On a per capita basis, the average annual surplus in the EU5 is €4,700 ($5,900), almost 50 percent more than the €3,200 ($4,000) average surplus in the 13 markets surveyed. Europeans benefit from both lower costs and higher value. The surplus that consumers in the EU5 receive from the mobile Internet in terms of communication, consumption, commerce, and information is about 13 times what they pay, almost twice the average (of 7 times the amount paid) across the 13 markets. (See Exhibit 5.)

German users generate the highest consumer surplus per person (€5,100), as well as the largest total consumer surplus in the EU5 (€199 billion). The UK has the second highest total surplus, followed by France. In Europe, as elsewhere, the Android operating system generates the largest surplus share, owing to the lower average cost—and generally high value—of Android devices and their resulting popularity. Apple’s iOS generates the largest surplus per person. (See Exhibit 6.)

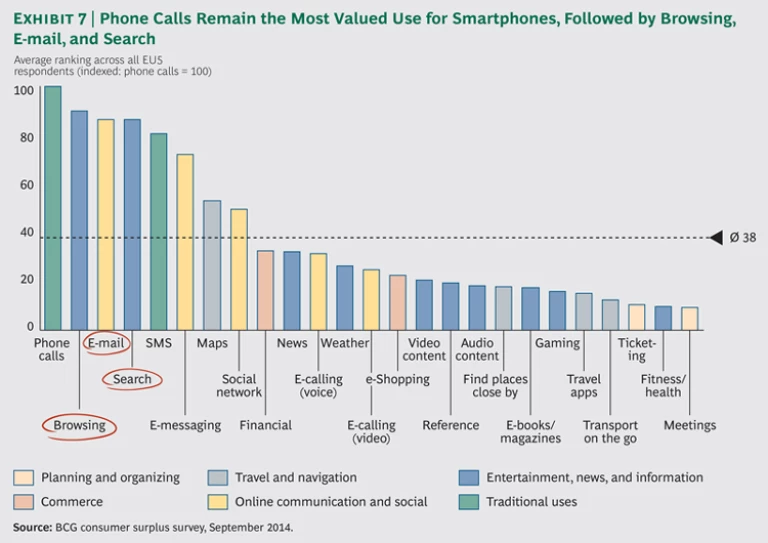

Consumers use their mobile devices for a wide variety of purposes. In Europe, the most valued feature is still phone calls, but this is followed closely by Web browsing, searching the Internet, and e-mail. Mapping capabilities, social networking, and financial functions are also very popular. (See Exhibit 7.)

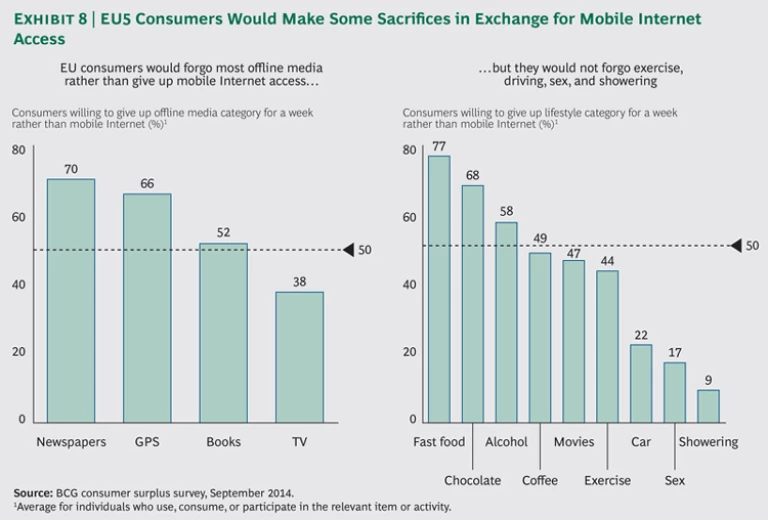

It’s no exaggeration to say that consumers everywhere have come to depend on the mobile Internet. Whether it’s for communication, consumption, commerce, or information, they are loathe to give up the capabilities that the mobile Internet confers. Large majorities of Europeans and other consumers would forgo most offline media (the one exception is TV) before forgoing mobile Internet access. Substantial majorities are also willing to give up such luxuries as fast food, chocolate, alcohol, coffee, and movies. Europeans are somewhat more restrained when it comes to such trade-offs and are more likely to put a higher value on cars, sex, and showering. (See Exhibit 8.) A significant minority of consumers (14 percent in the EU5) are not willing to give up their mobile Internet access at any price. As one person put it, “The Internet is part of my body. I feel the Internet running in my blood. I’d rather give up something else than this.”

The Mobile Internet Stack

The mobile Internet ecosystem is big and complex, involving thousands upon thousands of individual companies and organizations that interact with one another in countless ways. Some of these entities are global in scale and reach, employing thousands of people and generating billions of dollars of revenue—telecommunications providers, device manufacturers, and software companies, for example. Many have multiple products, services, business units, and profit centers—think Apple, Google, and Amazon. Others are as small as an individual app developer working on a PC (or tablet) at his or her kitchen table.

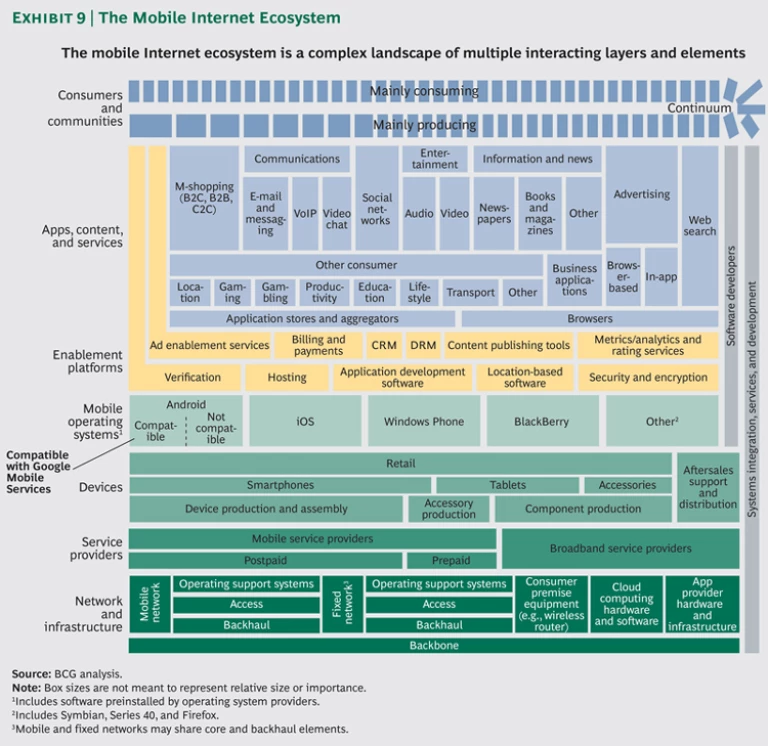

A Multilayered Stack

To illustrate the structure of the mobile Internet ecosystem, and how all these disparate players fit together and interact, we have borrowed from network engineering the concept of the “stack,” a set of layered software and hardware that work together to drive a computer or other device. Each layer of the stack is made up of competitors and collaborators, interacting among themselves and with the other layers to provide services to the layers above and ultimately to the end user. The skeleton of the stack is a set of rules, usually technology paradigms, laws, and government and industry regulations that define how groups coexist and co-participate. Stack architecture is typically found in information services, but it is now starting to emerge in health care and other industries.

The foundation of the mobile Internet stack is the physical infrastructure—the mobile and backbone networks that provide the necessary connectivity and bandwidth, without which the stack could not function. Next come the mobile and broadband service providers that facilitate network access for users. Mobile devices, manufactured and marketed by OEMs in partnership with the companies providing the mobile operating systems (and sometimes also with telcos), occupy the next layer. The mobile operating systems that power smartphones, tablets, wearables, and other devices occupy their own layer of the stack, followed by enablement platforms, which handle everything from hosting to security to billing and payment. (Some vertically integrated companies, such as Apple, operate at multiple layers of the stack.) Near the top of the stack stand the app developers, content creators, software providers, and social networks. At the very top are consumers and communities—the people and organizations that make use of all the layers below in their interactions with one another. (See Exhibit 9.)

The economics and nature of competition vary considerably within layers of the stack. The app market, for example, is international in scope, but a significant portion comprises apps that are entirely local in nature (for such reasons as language and culture). There are several big, global names in content (music and video, for example), but also some strong national and regional players—as well as millions of users. Dailymotion.com, a French video website, has 20 million unique visitors who generate 2.5 billion video views each month. M-commerce has both big international names (Amazon and eBay are two) and strong local and regional flavors (such as Alibaba in China and Flipkart in India), thanks to differing consumer tastes and supply chain considerations. Traditional retailers are rapidly blurring the lines between digital and brick-and-mortar commerce, adding further complexity to the mobile stack. (See “ The Mobile Internet Takes Off—Everywhere ,” above.)

The enablement platforms layer consists of services such as ad placement, billing and payments, identity verification, and publishing tools; it involves global companies like SAP, Spring Wireless, IBM, and Woodwing. Likewise, device manufacturers tend to be global businesses, with a wide range of companies (Samsung, Apple, LG, Nokia) competing across countries and regions. For legacy and regulatory reasons, the service providers—telcos—are primarily national or multilocal companies. Some are developing regional strength—four carriers are active across multiple European countries, for example.

The Mobile Operating System Layer

The center layer of the mobile stack is occupied by the operating systems that make smartphones smart and that enable the convergence of computing power and portability in tablets and turn wearables into something much more than a wristwatch or an article of clothing. This layer is particularly dynamic and fast changing. Understanding distinctions among the major operating systems, each of which has its own goals, strategies, and impact, is essential to grasping how the mobile Internet industry works.

The operating system and device layers of the stack are both very fluid, and the size, roles, and influence of the various players have shifted dramatically over time. (See Exhibit 10.)

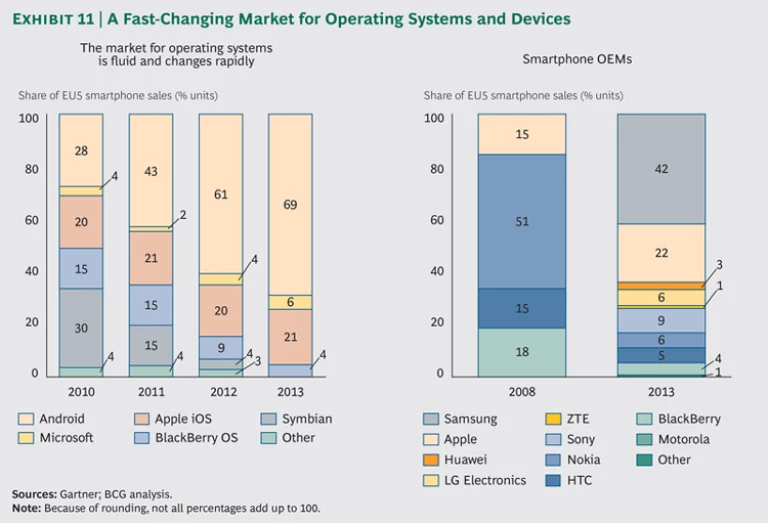

Nokia and BlackBerry accounted for more than two-thirds of smartphone sales in 2008. As recently as 2010, four major operating systems (Nokia’s Symbian, Google’s Android, Apple’s iOS, and BlackBerry OS) shared 93 percent of smartphone unit sales in the EU5—with BlackBerry and Symbian accounting for more than 45 percent. (See Exhibit 11.)

Today, Android accounts for 69 percent of devices sold in the EU5 and iOS accounts for 21 percent, while BlackBerry and Symbian have fallen to 4.2 percent and less than 0.5 percent, respectively. Android and iOS also account for most of the value generated in the EU5. (See Exhibits 12 and 13.)

Each of these operating systems has very different goals and strategies. Android aims to increase mobile Internet usage with an open-source operating system that is given away free with few restrictions. Android’s ultimate goal is to provide as many users as possible with access to the Internet, thereby maximizing revenues through the use of Google’s search and advertising services. Because device makers can install the operating system at no cost and differentiate on top of it, Android furthers competition among manufacturers and lowers costs for consumers. Its open-source architecture means it has many partners across multiple layers of the stack.

While Android supports a diverse set of devices, many at low price points, Apple focuses on selling premium devices that perform at a high level through the tightly controlled vertical integration of Apple computers, phones, tablets, other devices, and the apps they run. To deliver on its brand promise, Apple develops innovative products that depend on the tight control of the user interface and experience. Its highly integrated model imposes exacting design criteria and standards on its partners. The resulting products appeal to many users: Apple is the world’s most valuable company by market capitalization.

Two other operating systems together share about 10 percent of the EU5 market. Microsoft is building a third major ecosystem with its Windows Phone by leveraging the strength of its brand, its powerful desktop operating system, and its vast experience and capabilities in software design. It also aggressively promotes its cloud-based software and services. BlackBerry, once the market leader in corporate or “enterprise” mobile services, aims to sell devices, software, and services to the enterprise market based on its secure operating system and messaging services as well as a predictable user experience. Its recently announced partnership with Amazon Appstore signals an intention to focus resources on enterprise services and phones, while relying on Amazon to address the consumer side.

Today’s lineup will almost certainly change as current players and other competitors develop new technologies and services. Newer operating systems, such as Amazon’s Fire OS, Nokia’s X platform, Xiaomi MIUI, Firefox OS, and Tizen, are increasing both user choice and competition in the stack while decreasing prices. Fire OS and X platform are both Android “forks,” or altered copies, that legitimately use variations of the open-source Android operating system to pursue their own directions. In fact, few device OEMs today use a “pure” version of Android. Google makes the entire source code freely available for modification through the Android Open Source Project, and each OEM can decide whether it wants to include Google Mobile Services (Google Play, for example) on its devices. Those that do must have their device and operating system specs checked (using Google certification tools) to ensure that all app programming interfaces are supported. Although OEMs can still make modifications to the user interface and user experience to differentiate their devices in the marketplace, Android’s baseline compatibility standards aim to reduce fragmentation.

Other OEMs take a different route, choosing to install their own versions of these apps or services instead of Google Mobile Services. To do so, they must have access to an alternative source of apps, and no further interaction with Google is required. Examples of this approach include Amazon’s Fire OS, which seeks to create its own ecosystem of devices and apps built around its e-commerce model, Nokia’s X line series of devices, and MIUI, the brainchild of China’s largest smartphone vendor. (MIUI does not include Google apps in the Chinese market, but they are included in other Asian markets such as India, Singapore, and Indonesia.) MIUI pursues a low-cost, low-margin model that is engendering intense competition across Asia and will likely expand beyond the region to increase competition elsewhere.

The Firefox and Tizen operating systems are both based on Linux. Like the popular Firefox Web browser, Firefox OS was developed by Mozilla. It is designed to compete in price-sensitive markets, and the first Firefox OS phones are intended to bring better performance to the low end of the market. Mozilla and its partners are also expanding into midtier devices. Intex Technologies has launched a $33 Firefox OS smartphone in India in an attempt to undercut affordable smartphones from Google’s Android One program, which retail for closer to $100. Tizen, sponsored by Samsung and Intel, among others, serves two purposes: it provides its sponsors, which include device makers, semiconductor manufacturers, and telecoms, with an alternative to Android, and—by developing a well-resourced and strongly backed competitive open operating system—it encourages Google to preserve the openness of Android.

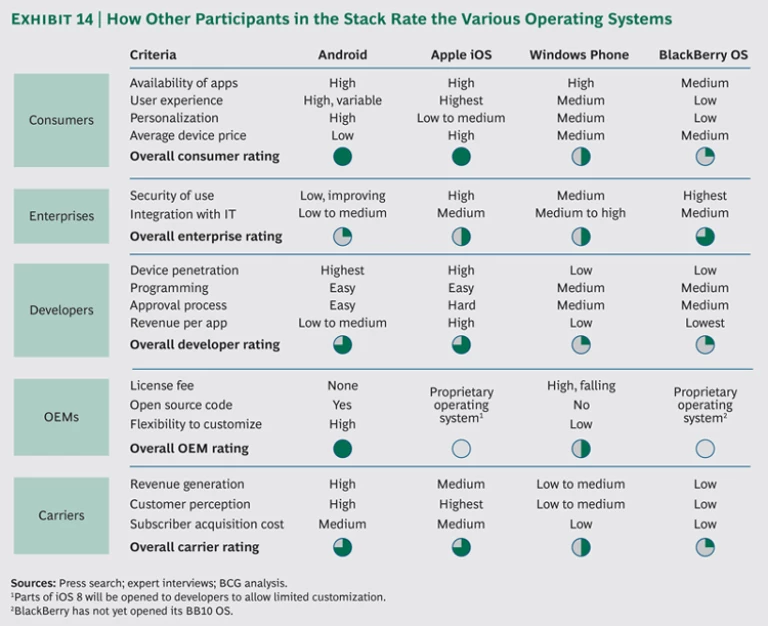

The Great Debate: Open Versus Closed Systems

In recent years, competing operating system strategies have emerged, each with variations on open or closed models. Android grants OEMs full access to its operating system code. Windows is available on Microsoft phones and on those of licensed third-party OEMs. BlackBerry’s proprietary system is available only on BlackBerry handsets. Finally, Apple iOS is a vertically integrated operating system available only on iPhones and iPads. Industry participants debate which is preferable, and each offers advantages and disadvantages to consumers, device makers, and developers. The attributes of each determine how the company behind the operating system interacts with other participants in the stack. (See Exhibit 14.)

Broadly speaking, open-source operating systems, which can be modified and adapted by OEMs, have many participants involved in system development, device manufacturing and marketing, and app development and marketing. Each device manufacturer does business independently of the operating system developer, and multiple app vendors operate under more loosely controlled standards and testing. The leading example, of course, is Google’s Android and its many device manufacturers.

In closed systems, by contrast, proprietary code is not made available to OEMs or other participants. There is tight vertical integration across the system developer, device OEMs, and app vendors. These operating systems typically involve only a single or small number of device manufacturers and a single app store with strictly controlled standards and testing.

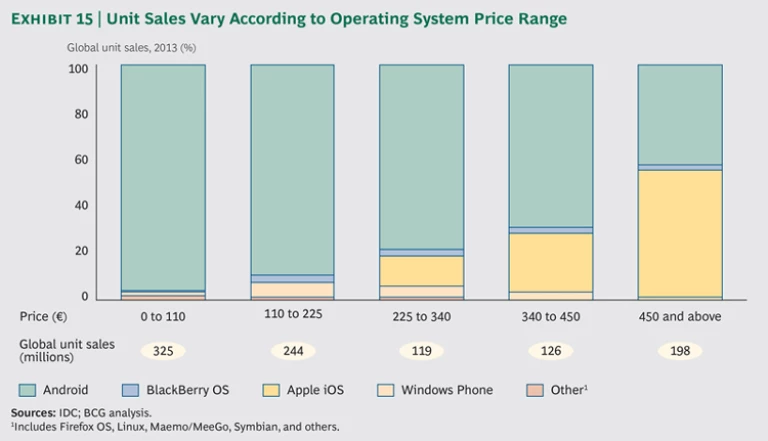

Open systems generally provide consumers with greater choice when it comes to operating systems and devices (remember that there are more than 18,000 Android-powered device models). These include “pure” Android systems, Android-compatible OEM modifications, and Android “forks.” Consumers also have more opportunity to customize the device experience (for example, by personalizing the look, feel, and features of their smartphones). And app developers are often able to more deeply integrate with open systems, creating further differentiation and customization. The various “launcher” apps that are available on Android enable users to opt for a completely different user interface than the one that comes preinstalled on most devices. Finally, open systems tend to lead to a greater range of price points, since multiple OEMs control the pricing of their respective devices. (See Exhibit 15.)

Open access to source code and device features promotes innovation, but it can also mean that features are not fully tested on all devices and may be less reliable. The forking of an operating system can reduce its scale of use and hence developer interest, and consumers can find that forked systems don’t run all apps properly. There is also a higher potential for security flaws on noncompatible forked operating systems (malware, spyware, privacy violations), and multiple app stores create more potential sources of security attacks.

Closed systems, in contrast, offer consumers a limited number of one-size-fits-all devices that are typically made available at few—and often premium—price points. Apple, for example, offers two sizes of its iPad tablet, which is available in black, white, or—as of 2014—gold. Many features are not customizable, but since all have usually been fully tested on all devices, they are always reliable. Apps are available only from a single app store, which can limit choice but is an effective means of reducing security attacks and risks for users.

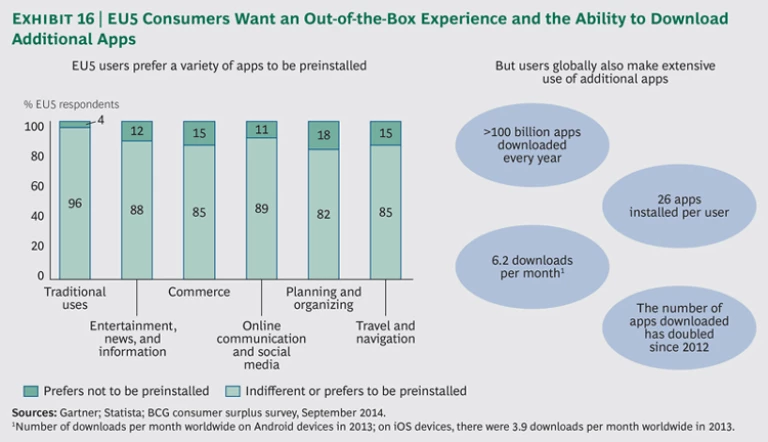

Whether the operating system is open or closed, consumers’ priorities are in certain respects consistent: they want a ready-to-go, out-of-the-box experience combined with the flexibility needed to download supplemental apps. (See Exhibit 16 for the preferences of consumers in the EU5.)

For developers, the greater consumer choice provided by open systems leads to a more segmented market that spans many price points. With open systems, no single app store is the sole “gatekeeper,” with the power to control market access for a developer’s app; developers have multiple options to get their apps onto devices. The fragmentation of devices and operating system forks, however, adds complexity. Developers often must create multiple versions of the same app for each operating system flavor, and app performance may vary across devices. As a result, fragmentation can easily and quickly drive up development and support costs.

The often more focused ecosystem of a closed system can be attractive to developers, especially since users are often paying a premium for devices and apps. At the same time, the single gatekeeper app store can determine whether any single app gets access to the ecosystem. One large app store with exacting standards for a small number of devices means that developers typically only have to create one or a very few versions of a given app.

Competition among open and closed systems furthers innovation and keeps the mobile ecosystem thriving. In Europe and elsewhere, it drives rising revenues, the growing consumer surplus, investment, and jobs.

Keeping the Mobile Internet Moving

The economic benefits of the mobile Internet are big, clear, and undeniable. As we have seen, competition has driven innovation and experimentation that have generated billions of dollars in new economic activity, millions of jobs, and a large and growing consumer surplus. It should be a goal of European policy makers to keep the mobile Internet moving forward.

To be sure, the disruption that game-changing technologies such as mobile often cause creates issues for consumers and others that require full debate and fair resolution. One of the most important of these is data privacy, data security, and the ways in which data is used by those that collect it. We have discussed previously the need to balance the potential value that personal data can unlock with the rights of individuals and societies to determine what are, and are not, legitimate uses of data. (See “ Rethinking Personal Data: Strengthening Trust ,” BCG article, May 2012.) There are also concerns about new business models, such as those at work in the “sharing economy” that create considerable consumer value but disadvantage legacy companies that often have to adhere to different sets of rules. Some consumer advocates and others point to the potential for overcharging consumers through in-app purchases and other subscription models, the cost ramifications of which some consumers may not fully understand. (Earlier this year, after discussions with industry players, the European Commission and the EU member states launched a coordinated action with respect to in-app purchases associated with online and mobile games, asking Apple, Google, and relevant trade associations to provide concrete solutions across the EU.)

These are all legitimate concerns. In Europe as elsewhere, policy makers can help keep the mobile Internet economy moving by pursuing proven policy goals that can mitigate risks to growth and encourage innovation, value creation, and consumer welfare and choice. The European Digital Single Market initiative, for example, should help app developers and others reach multiple markets much more quickly with new products and services. Other policy goals should include the following:

- Promoting investment in expanded coverage, high-speed infrastructure, and affordable mobile Internet access

- Putting a priority on education and skills building

- Encouraging innovation and entrepreneurial activity

- Adapting existing legislation or policies to allow for the growth of new business models that create consumer value

- Encouraging organizations to be clear about the collection and use of customers’ data and to follow sound practices when charging for in-app purchases and subscriptions

In addition, policy makers need to take into account how quickly technologies and the innovations they enable are evolving and, where necessary, modernize regulatory regimes and regulations in ways that support innovation and investment across the entire mobile Internet value chain. Simple, transparent, ex ante policies work best in fast-changing environments. Existing regulations should be reviewed for the possibility of reducing or eliminating rules that impede technological innovation and business model experimentation. And taxation of digital activities should not become an undue burden for the sector, as it may undercut innovation and stunt the growth of independent developers. Governments should avoid, or look for alternative approaches to, adding new regulations or expanding existing regulations to new sectors. In some instances, self-regulation can be a viable option in competitive markets.

Policy makers also need to recognize that, like individual countries and markets, companies and organizations operating at each layer of the stack face different kinds of challenges. (See “ The Mobile Internet Stack ,” above.) As we argued in “Reforming Europe’s Telecom Regulation,” for example, there is a need for reform at the network and infrastructure layer of the stack on the specific issues facing Europe’s telcos. In other parts of the stack—the operating system; device; and apps, content, and services layers being three examples—the market economy is doing its job quite handily. Competition reigns, prices are falling, innovation is bringing new technologies, products, services, and apps to market at a near breakneck pace. And consumers are realizing a huge and growing benefit. The mobile Internet economy is creating jobs and making a material contribution to GDP.

We are still only starting to realize the benefits of the mobile Internet for consumers, businesses, and society. These benefits are built, fundamentally, on competition-driven consumer choice and access. In an age of globally mobile capital and talent, the economies that develop and maintain such markets will see the greatest payback.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to the following partners and colleagues for their insights and assistance with the development of this report: Philip Evans, David Brooks, Samuel Cohen, Caterina Preti, Henry Fovargue, Marcus Müller, Gaby Barrios, and Emmanuel Huet. In addition, they would like to thank Arnaud Miconnet of Sunesis Research.