In recent years much has been said and written about Africa’s emerging class of consumers, who are often described as inexhaustibly optimistic, highly brand conscious, Internet savvy, eager to spend, and willing to pay more for quality. These generalizations appear to herald the arrival of a new and meaningful consumer base. Yet the details about African consumers’ specific attitudes toward spending, brands, and the media, and how demographic differences affect those attitudes, have been largely absent—until now.

BCG’s 2013 Africa Consumer Sentiment Survey, which polled 10,000 consumers across eight of the continent’s largest countries, provides a quantitative database that supports the theory of not one but many consumer classes emerging across the continent. (See “2013 Africa Consumer Sentiment Survey.”) The male and female consumers we interviewed represent a broad range of ages, incomes, education levels, and household types. In addition to exploring the current spending behaviors of African consumers, we asked about what they intended to purchase and how much they planned to spend with regard to more than 20 different product categories, ranging from appliances and automobiles to clothing and snack foods.

2013 AFRICA CONSUMER SENTIMENT SURVEY

For more than ten years, BCG has conducted an annual Global Consumer Sentiment Survey to gather information on consumer behaviors and trends across many countries. In 2013, for the first time, BCG added several African countries to the survey, enabling comparisons across the continent and with other emerging markets, such as China, India, and Brazil, as well as with mature markets. Altogether, the global survey reached 40,000 consumers in 25 countries and was conducted in 20 languages.

In Africa, we surveyed nearly 10,000 urban consumers in eight countries: Algeria, Angola, Egypt, Ghana, Kenya, Morocco, Nigeria, and South Africa. Respondents represented a mix of consumers of different ages and different income and education levels. The survey explored topics related to income, spending, and budgeting; technology, mobile, and Internet usage; preferred retail-shopping locations; and banking habits.

Additionally, the survey assessed planned expenditures, trading up and down, brand preferences, and shopping behaviors in 20 product categories: automobiles; baby and toddler products; beauty care; beer; breakfast cereals and foods; chocolate and candy; clothing, footwear, and accessories; coffee and tea; consumer electronics; hair care products; health care; home appliances; insurance; mobile phones and devices; packaged food; restaurants and out-of-home eating; snacks; soft drinks and other nonalcoholic beverages; spirits and other alcoholic beverages; and wine.

Note: This sidebar originally appeared in Winning in Africa: From Trading Posts to Ecosystems (BCG report, January 2014). The Global Consumer Sentiment Survey is sponsored by BCG’s Center for Consumer and Customer Insight and funded by the firm’s Global Advantage and Marketing and Sales practices.

Many Markets, Many Consumers

Our research reinforced the fact that there isn’t just one monolithic Africa. Rather, the continent is a collection of many different countries, markets, and consumers—or “many Africas.” Our findings fall into five categories: the optimistic and pragmatic African consumer; the demand for durable goods; the power, promise, and perils of branding; the smart, sophisticated, and selective shopper; and the need for a mix of marketing channels. Taken together, the results paint a clear picture of Africa’s emerging consumer classes. The insights and strategic implications presented in this report can provide critical information for companies seeking to make competitive inroads into these diverse markets.

The Twenty-First-Century African Consumer: Optimistic and Pragmatic

Almost 90 percent of the African consumers we surveyed—well above the global average of 54 percent—said that they are generally optimistic about the future. Despite this optimism, however, many also feel at risk: 43 percent of African consumers either believe that they are in financial trouble or do not feel financially secure, compared with just 13 percent of consumers in India and 12 percent in China. As a result, many Africans are saving for an “unexpected future”—building financial cushions to have cash available for events that they can neither control nor plan for. From 32 to 59 percent of respondents said they’re putting aside money in case of an emergency—a top reason for saving in other parts of the world as well. In many African countries, savings as a percentage of monthly income are comparable with those in developing economies such as Brazil, China, and India, although savings rates vary across Africa and were less pronounced in North Africa. Moreover, fewer Africans are saving to purchase a home, car, or other big-ticket item compared with consumers in other developing economies.

When we examined each African nation individually, striking differences emerged. At the time of the survey, consumers in Egypt were the least bullish on the future, with only 66 percent feeling somewhat or very optimistic. They also reported the lowest savings rates, which is not surprising given the extreme uncertainty during the civil unrest in 2013, when many people were likely spending to acquire basic necessities rather than saving. Meanwhile, more than 70 percent of consumers in Angola reported some degree of financial insecurity, despite savings rates that are higher than average. Ghana had the highest savings rate, with 81 percent of respondents claiming that they save more than 5 percent of their income.

Although they’re putting money aside for a rainy day, African consumers are also eager to spend. Quite simply, buying makes them happy. More than 80 percent of the people we interviewed said that the ability to buy new things brings them happiness, compared with slightly more than 70 percent in other developing nations—such as Brazil, China, and India—and less than 60 percent in developed countries. According to our survey, 60 to 90 percent of consumers in each of the eight African countries we visited expressed a strong desire to buy more things every year—again higher than the averages in Brazil, China, and India, and twice the percentage of consumers in developed nations. Like consumers in other developing countries, Africans are beginning to embrace consumerism, with 65 percent agreeing that the desire and ability to buy products move the economy and culture forward. In contrast, only 30 percent of African consumers said that they already have enough things—a much lower percentage than in other developed and developing nations. This suggests a pent-up demand for new products and services.

The Demand for Durable Goods: Driving Spending in Africa

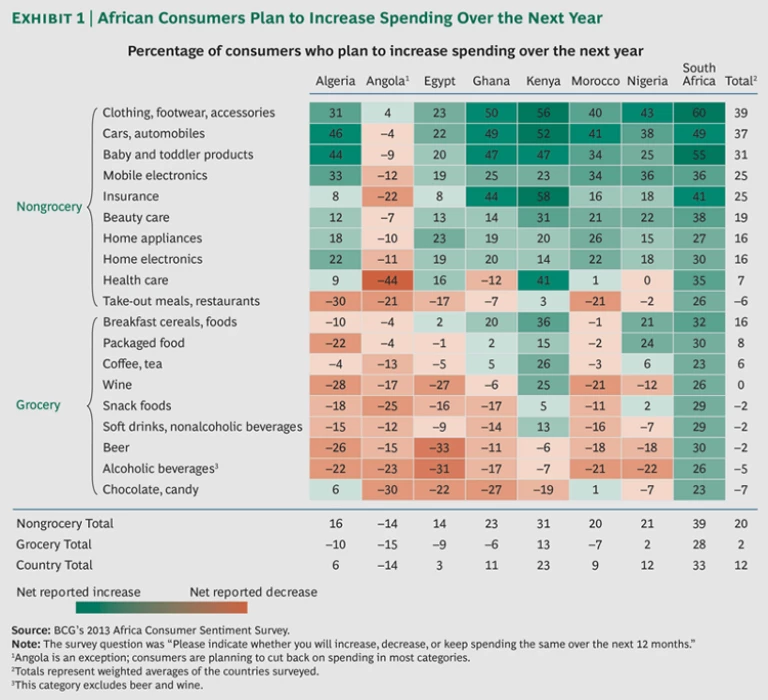

It’s not surprising, then, that the majority of respondents in Africa said that they intend to spend more over the next 12 months, and those expenditures are planned mostly for durable goods such as apparel, cars, and consumer electronics rather than on perishable food and grocery items. (See Exhibit 1.) The people we interviewed plan to spend more on clothing, cars, baby and toddler products, and mobile electronics, and to reduce their spending on restaurant and take-out meals, chocolates and candy, and alcoholic beverages.

Variations across countries are striking. Angola is the only nation where more consumers plan to decrease rather than increase their total spending. There, consumers are planning to spend less across all categories except clothing, with the majority cutting back on health care, chocolates and candy, and snack foods. In contrast, South Africa has the highest number of consumers planning to increase their total spending in all categories—although the increase is greater for durable, nongrocery items and lesser for breakfast foods, packaged food, and beer. Consumers plan to spend more on health care over the next year in Algeria, Egypt, Kenya, and South Africa but less in Angola and Ghana.

The increasing number of middle-class consumers is well documented. But often overlooked are the low-income and bottom-of-the-pyramid consumers who also shop and are already buying and willing to trade up for international brands. In fact, the total number of consumers who are likely to buy any given product may be larger than many companies believe.

Taken together, these findings bode well for companies targeting African markets. According to our research, highly optimistic consumers are more likely to spend, although consumers in Angola and Egypt may be less open to making discretionary purchases. Overall, however, the market for new products and services in specific African nations appears especially attractive as new consumer classes emerge.

The Power and Promise of Brands—and the Perils of “One Size Fits All”

Brands are powerful in Africa, but favorites vary by country and age group. A one-size-fits-all approach won’t work on this diverse continent. African consumers are highly brand conscious compared with consumers in other countries around the world, and they report a strong and complex emotional connection with their favorite brands. According to our survey, almost 70 percent of Africans feel that brands represent who they are, validate and communicate their personal values, and provide a sense of belonging, compared with only 40 percent of consumers in Brazil, 29 percent in China, and 24 percent in developed markets.

Interestingly, income is not the biggest indicator of brand preferences, and consumers at all income levels believe that brands have the power to contribute to self-expression and personal identity. Brands appear to be particularly important for status items, such as clothing and cell phones, and durable goods, such as appliances and electronics. They appear to be relatively less important for consumable items such as snack foods, beverages, and other food items with a high rate of turnover on store shelves. Of course, the relative strength of a brand is also a reflection of how much a company has invested in brand building in a given country. Multinationals with global brands have the advantage of scale over local brands, which tend to be more fragmented.

Brand attitudes can often be in conflict, however. Although 70 percent of consumers in Africa believe that established brands are the best—compared with a global average of 38 percent—they are also three times more likely than consumers in other countries to express disdain for their parents’ brands. On the surface, this suggests that multinational companies with well-established and well-known brand portfolios formally entering the African market for the first time could be positively received by a consumer base clamoring for brands that are new to them. It also underscores the importance of rebranding or remaking more traditional brands to better resonate with a changing, more sophisticated, and more demanding African consumer.

Friends and social networks also strongly influence which brands people buy. Africans in our survey were twice as likely as consumers in other countries to decline to purchase a brand or product that their friends disapprove of. In short, African consumers prefer brands that they know, that are familiar to them, that speak to their generation and values, and that are socially acceptable to their peer group.

Brand awareness and recall vary greatly across product categories. While only 68 percent of consumers surveyed could name a favorite brand of medicine, 99 percent could recall a favorite brand of mobile phone, and 89 percent could name a favorite clothing brand—not surprising given the more durable and status-oriented nature of those categories. One unexpected finding is that brands remain important even as income declines. For example, when we asked consumers whether they agreed or disagreed with the statement “Brands say something about who I am, my values, and where I fit in,” 68 percent of the lowest-income consumers—those with household incomes of less than $300 per month—agreed. Similarly, 71 percent of the highest-income consumers—those with household incomes of more than $3,000 per month—also agreed with that statement. Clearly, high brand consciousness exists across all income levels in Africa—at least for some products.

Certainly African consumers are enamored with global brands, but favorites vary by country and product category. (See Exhibit 2.) For instance, 36 percent of consumers in Ghana cited the local brand GoldenTree as their favorite candy, more than three times the number of respondents who preferred Mars, the second most popular brand. But in Nigeria, where consumer favorites are more fragmented, international brands dominate the list of top candies, with Snickers (11 percent), Mars (8 percent), Kit Kat (6 percent), Cadbury (5 percent), and Bounty (5 percent) named most often. In sub-Saharan Africa, favorite brands of beer and restaurants tend to be local or regional rather than global.

That said, African consumers expressed a clear preference for global brands across categories such as mobile electronics, home electronics, and automobiles. The home appliance category, for instance, is dominated by well-known, established global brands such as LG, Samsung, and Sharp, even though the category is highly fragmented. In fact, LG was cited as the favorite or second favorite home-appliance brand by consumers in six of the eight countries surveyed.

Quality, performance, and familiarity were the top reasons given for choosing a brand. In each sub-Saharan country, more than 60 percent of respondents cited better quality as the top driver of brand favoritism and nearly half mentioned best performance. Across the continent, the primary reason given for not purchasing favorite brands was affordability, although in Nigeria and South Africa four out of ten respondents also noted a lack of availability where they shopped. Lower-income consumers in Nigeria were more challenged by availability than high prices when shopping for their favorite brands.

These findings suggest that many well-known global brands already have a head start in Africa. But to succeed there, global brands will also have to create an emotional connection with target consumers along specific dimensions, such as values, beliefs, and family—even more so than in other countries. What’s more, multinationals can drive growth by playing up the brand and product attributes that appeal to African consumers—such as quality, performance, and familiarity—and by addressing the obstacles that tend to hinder purchasing, such as price and availability.

Smart, Sophisticated, and Selective: Value Matters in Africa

Perhaps because disposable income is limited, African consumers are selective and smart about what they purchase. Of the people we interviewed, 70 percent said they knew a lot about the details of the products they buy. When compared with a global average of 57 percent, this suggests that African consumers are both knowledgeable and diligent in their decision-making process.

Rather than buying indiscriminately, 74 percent of African consumers, compared with a global average of 67 percent, said they focus their spending on the few product categories that matter most to them. Important categories, where consumers are most willing to trade up and least willing to trade down, include clothing, health care, and baby products. Less than a third of consumers said they want to spend the bare minimum or to save money in those categories. Moreover, almost 75 percent reported saving and cutting back on spending in other areas to pay more for products that are important to them. Consistent with consumers in other developing economies, 72 percent of African shoppers said they value quality over quantity; the global average was 53 percent.

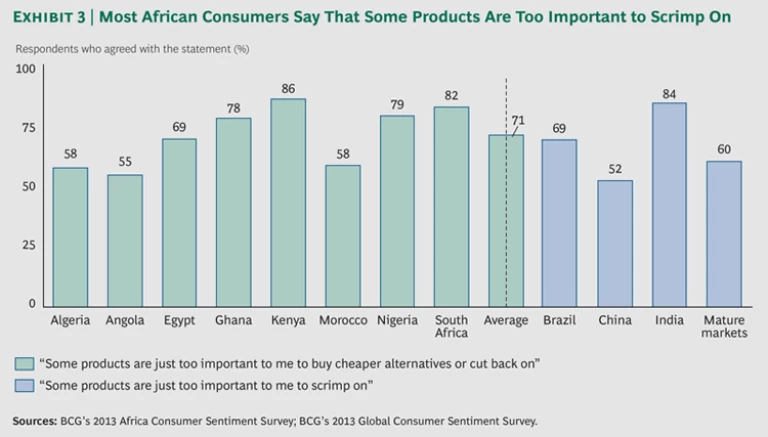

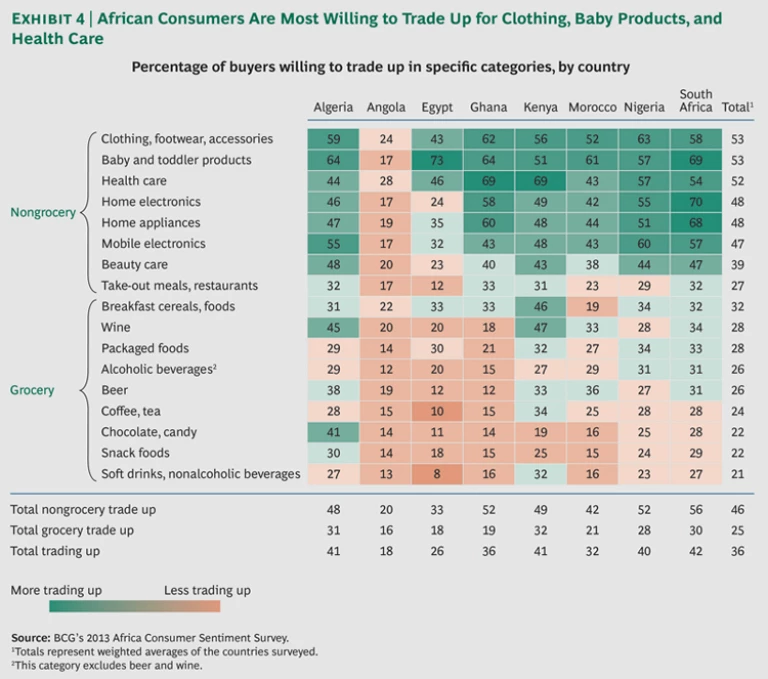

This focus on quality also affects decisions about trading up and trading down. Of the African consumers we interviewed, 71 percent—compared with 60 percent on average in mature markets—said that some products are just too important to swap for cheaper alternatives or to cut back on. (See Exhibit 3.) While all consumers consider some products to be of paramount importance, the categories they value can differ. For example, only a third of lower-income Nigerian consumers are willing to trade up on home electronics, while more than 90 percent of Nigerian consumers making more than $20,000 per year said they are willing to pay more for items such as stereos and TVs. By contrast, few consumers are willing to pay more for a product when a less expensive alternative exists and they perceive no meaningful differences between the two.

As a rule, African consumers will trade up for quality and trade down to economize and stretch their budgets. About half of the respondents reported that they are more willing to pay a premium for nongrocery categories, such as clothing (53 percent), products for infants and toddlers (53 percent), and health care (52 percent). (See Exhibit 4.) More than 40 percent are inclined to trade up for durable goods, such as mobile electronics, home electronics, and home appliances. On the other hand, groceries are shaping up to be a competitive, low-margin category. Few African consumers plan to increase their spending in this category, and many plan to trade down.

Where do African consumers make their purchases? Although most shoppers go to traditional retail outlets such as shops, markets, and kiosks, these local venues are giving way to a wider range of more modern formats. Many African consumers said they now shop for consumer durable goods and packaged food at specialty retailers, hypermarkets, and supermarkets. Pharmacies and clinics are the primary source for health care products and services. But here as well, retail preferences vary greatly by country, income level, and product category. Since the marketing and distribution approaches that work in one African country may not work in another, companies must identify the leading retailers for specific products in different markets for the different consumer segments. The reality is that distribution and availability can be challenging for many products in Africa. Companies must also figure out where consumers seek their products and find ways to deliver to those outlets.

Clearly, African consumers have more disposable income and more choices than ever before. Still, their selectiveness is largely driven by necessity, and the need to economize leads to forced tradeoffs. Smart companies will invest in understanding these diverse consumers—and how their behaviors vary market by market—to determine which product categories are priorities, how much of a premium different products can command, and what it will take to win in those categories. Certainly, luxury categories with largely untapped potential do exist, but multinationals must evaluate the size of the market and how strongly a high price is associated with high quality. Moreover, given the changing retail landscape, companies must think carefully about product placement in African markets and optimize distribution accordingly.

Marketing Channels: Reaching the Many Africas

The importance of friends and family, particularly spouses, in the purchase decision-making process is clearly evident among the African consumers we spoke with, who tend to trust and respect the opinions of those closest to them. The Internet and social media are growing in importance as ways to stay connected and share opinions.

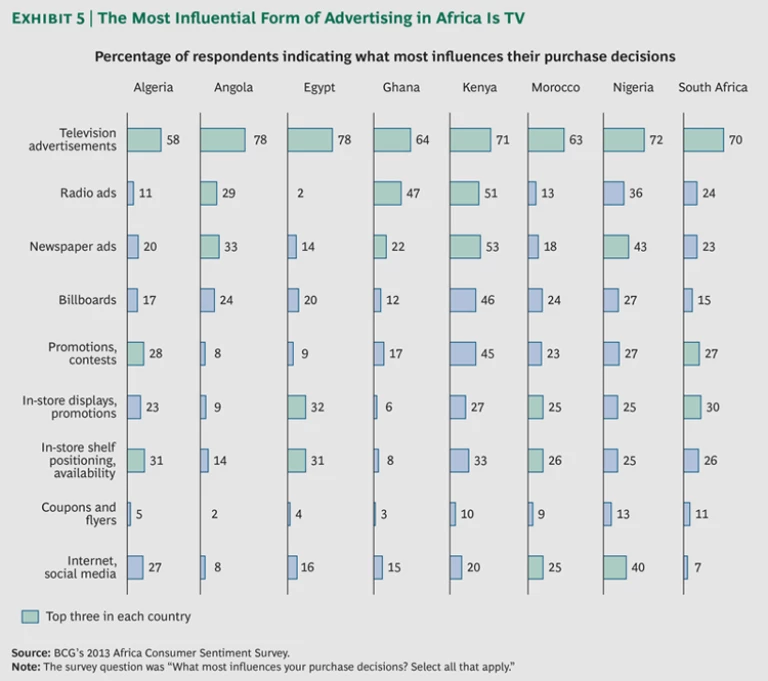

When it comes to mass media, almost three-quarters of the consumers we interviewed said that television ads have the biggest influence on their purchase decisions. (See Exhibit 5.) Our survey revealed nuances across countries, however. Radio is a greater influence in Ghana and Kenya than in other African nations, while newspapers are more influential in Kenya and Nigeria. Although the Internet and social media have minimal impact on purchase decisions today, these online channels are gaining traction in some countries, including Algeria, Morocco, and Nigeria. In Nigeria, for instance, 40 percent of the consumers we interviewed reported being influenced by online product reviews and blogs. Not surprisingly, demographic differences also come into play. A higher percentage of wealthier consumers (60 percent of households with annual incomes of more than $20,000 and 54 percent of households earning from $10,500 to $20,000 per year) and younger consumers (50 percent of those ages 18 to 24) said they were influenced by the Internet.

Although African consumers have broad access to the Internet and some spend a great deal of time online, e-commerce opportunities are still largely in the future. Sixty percent of the people we interviewed reported having Internet access, and about half of those with access spend more than two hours a day online. Still, in most African countries, less than 10 percent of consumers said they make online purchases; Nigerians are most likely to do so. Although they’re not buying products, consumers do research products, search for information, and educate themselves online.

In terms of how they access the Internet, 58 percent of the people we interviewed use their mobile phones, 37 percent use laptops, 23 percent use desktop computers, and 11 percent use tablets. About a quarter of respondents go online at work, and less than 15 percent use Internet cafes or other public places. Our survey revealed regional differences, however. Most North Africans, for instance, access the Internet at home: 77 percent in Egypt, 63 percent in Morocco, and 59 percent in Algeria. Yet, with one exception, sub-Saharan consumers prefer to use mobile phones: more than 80 percent of Kenyans, Nigerians, and South Africans chose this option. The exception is Angola, where consumers prefer to go online at home, using either a desktop or a laptop.

To capitalize on this growing market, companies must develop digital strategies and integrate their online and offline marketing. Moreover, given the growing number of African consumers who use mobile phones to access the Internet, optimizing the mobile experience should be a priority. Until e-commerce takes off, smart companies will use digital channels to build their brands, engage consumers, provide product information, and drive offline sales. When the online marketplace matures, these forward-looking companies will be well positioned to drive online purchases.

Companies that succeed in Africa’s many markets will have a deep understanding of how consumer preferences and behaviors vary across the continent—often in very nuanced ways—according to income, gender, age, location, and other factors important to a particular product category. Achieving this degree of understanding requires an investment in data collection and analysis, on-the-ground observation, and carefully developed insights into different consumer segments and their needs. Only companies with this degree of granular information will be able to make the right branding, packaging, pricing, marketing, and distribution decisions for Africa’s many different countries, markets, and consumers.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Miriam Benedi, Belinda Gallaugher, David Michael, Carey Wikstrom, and Nomava Zanazo for their contributions to this report. They would also like to thank Martha Craumer for her assistance in writing the report.