You feel the energy soon after disembarking at Hazrat Shahjalal International Airport in Dhaka. All of Dhaka, the capital of Bangladesh, seems to throb with bustling masses of people. Bridges, expressway overpasses, and major new neighborhoods are continually under construction. Evidence of the country’s rising disposable income is on display at crowded shopping malls such as Jamuna Future Park, the largest in South Asia, and new billboards, which seem to cover every available space, advertise products as varied as packaged foods and smartphones.

To much of the outside world, Bangladesh remains synonymous with poverty. It is time to take a new look at this land of 160 million: this rapidly developing economy is one of the world’s next great growth markets for discretionary consumption.

Although the number of middle-class and affluent consumers in Bangladesh remains small compared with those of other big emerging markets in Asia, Bangladesh is one of the fastest-growing markets worldwide. We project that, each year for the next decade, the annual income of around 2 million additional Bangladeshis will reach $5,000 or more. That means that they will be earning enough to afford goods that offer convenience and luxury, such as air conditioners, imported shampoos, and cosmetics. And although half of Bangladeshis still live at the so-called bottom of the pyramid, economists estimate that another 30 million to 40 million will make the leap from poverty to the entry rungs of the middle class by 2025.

To help companies gain a deeper understanding of the middle and affluent class (MAC) in this increasingly important—but often neglected—market, The Boston Consulting Group’s Center for Customer Insight surveyed around 2,000 households across the country. We asked consumers about their sense of financial well-being, their purchasing habits, and their consumption priorities for some 70 product categories. To help companies anticipate when consumption is likely to take off in these categories, we also analyzed changes in Bangladeshi household consumption of specific goods and services relative to rising incomes.

The following are among our key findings:

- Bangladesh’s consumer class is swelling and dispersing. Although only some 7 percent of the country’s current population can be classified as middle income or affluent, compared with 38 percent in Indonesia, MAC Bangladeshis will account for around 17 percent of the population by 2025. Consumer wealth is also dispersing regionally: projections indicate that within the next decade, 63 cities will have MAC populations of at least 100,000, compared with 36 now.

- Consumers intend to spend but are wary of debt. Sixty percent of consumers report that they expect their incomes to rise over the next 12 months, and 69 percent say that there are more things they want to buy. But they are restrained by concerns—due perhaps to social taboos or to a lack of familiarity with debt instruments—that they will run up debt that they won’t be able repay. Alleviating this concern could unlock great growth opportunities.

- Consumers are highly loyal to brands, but they are also budget and quality conscious. Most Bangladeshi consumers—more than 80 percent in the case of durables—cite brand as a top factor that influences their buying decisions. These consumers work within a budget, and price is often cited as a second priority over quality. Far fewer Bangladeshis than consumers in Southeast Asian emerging markets say that price discounts sway their decisions.

- Consumers increasingly use the mobile Internet. Forty-one percent of Bangladeshi consumers surveyed—and 68 percent of MAC consumers—own Internet-enabled smartphones. Currently, most transactions are in cash, but the popularity of smartphones suggests that more consumers will be making the leap to mobile payment, creating an opportunity for reaching households through wireless mobile services. Eighty-one percent of consumers said that they trust what they read online, and 66 percent search for product information online.

Although these findings suggest that tremendous growth opportunities will unfold over the coming decade, companies must approach this market with a sophisticated understanding of the Bangladeshi consumer. They should also address the constraints that prevent consumers from acting on their strong desire to purchase brands and should introduce products that meet household budgets. Companies can expand their reach through different retail channels and in more locations.

For the next few years, companies should focus on ramping up their operations to meet growing demand from MAC households in Dhaka, Chittagong, and a handful of other cities. But at the same time, they should begin laying the groundwork for a broader expansion as the MAC population continues to grow and as buying power spreads swiftly throughout the country. The strong brand consciousness of Bangladeshi consumers suggests that the companies that can now establish themselves as trustworthy, build market share, and develop a reputation for delivering good quality will be those that reap the biggest rewards in what promises to be one of world’s next big growth markets.

Bangladesh’s Burgeoning Consumer Class

Despite having the world’s eighth-largest population, Bangladesh has been one of the least-noticed economic-growth stories, overshadowed by its giant neighbor, India, which surrounds it on three sides. Bangladesh’s economy is perhaps best known outside Asia for microcredit, pioneered by Grameen Bank, which dispenses small loans to village entrepreneurs. Its nominal per capita income, estimated by the World Bank at around $1,100, places Bangladesh on a level with much of sub-Saharan Africa.

Over the past decade, however, Bangladesh’s economy has been growing at an annual rate of 6 to 7 percent. Inflation has been moderate, and public debt levels low by world standards. Leveraging its huge, low-cost workforce at a time when costs in China have soared, Bangladesh has emerged as the world’s third-largest exporter of apparel, and exports of footwear, pharmaceuticals, and IT services are growing fast. Foreign direct investment is flowing into the manufacturing sector, while the government is stepping up investment in physical infrastructure. The economy is also benefiting from strong growth in remittances from Bangladeshis who work abroad, particularly in Persian Gulf economies and Southeast Asia. Moreover, Bangladesh also has a young and growing working-age population—the median age in the country is 24—that will provide a strong base for rising consumption in the coming decades.

Bangladesh’s strong and stable growth is fueling tremendous upward mobility. Tens of millions of Bangladeshis have been lifted out of poverty and propelled into the ranks of the middle class and affluent.

To measure this upward mobility, we segmented Bangladeshi consumers into five basic income brackets: bottom of the pyramid, which refers to five-member households subsisting on incomes of less than $150 a month; aspirant, $151 to $250; emerging middle, $251 to $400; established, $401 to $650; and affluent, more than $650. For the purposes of this study, we regard the last two income segments—established and affluent—as constituting Bangladesh’s MAC population, because they have attained the purchasing power to buy a broad variety of consumer goods and services and have acquired middle-class purchasing traits, such as buying goods that offer convenience and luxury in addition to basic necessities.

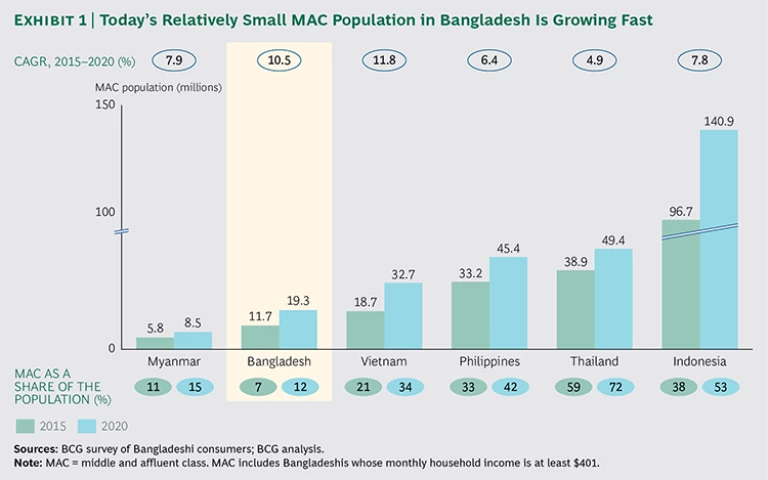

Bangladesh’s current MAC population, estimated to be around 12 million, is still small by Asian standards, accounting for only 7 percent of the country’s population, compared with 21 percent in Vietnam, 38 percent in Indonesia, and 59 percent in Thailand. This MAC population already represents a significant market for many global companies. These consumers also live in close proximity: Bangladesh has one of the world’s densest populations. Its 160 million people are packed into a territory roughly one-quarter the size of Thailand and one-third the size of Sweden.

What is even more important for consumer product companies is that Bangladesh’s MAC population is expanding rapidly—by an average 10.5 percent annually. That compares with 7.8 percent annual growth in Indonesia, 7.9 percent in Myanmar, and 4.9 percent in Thailand. (See Exhibit 1.) If Bangladesh can maintain this pace, its MAC population will grow by 65 percent over the next five years. By 2025, it is expected to nearly triple, to about 34 million.

Massive upward mobility among households at the lower rungs of the economy is likely to assure that growth in Bangladesh’s consumer class will remain robust for decades. Currently, some 84 million people—more than half of Bangladesh’s population—have incomes that classify them as being at the bottom of the pyramid. By 2025, however, we project that this group will shrink to 48 million. The aspirant income segment, meanwhile, will swell from 44 million people now to 64 million in 2020 and to nearly 92 million in 2025. The population of the next rung, the emerging middle, will increase from 17 million to 27 million in a decade.

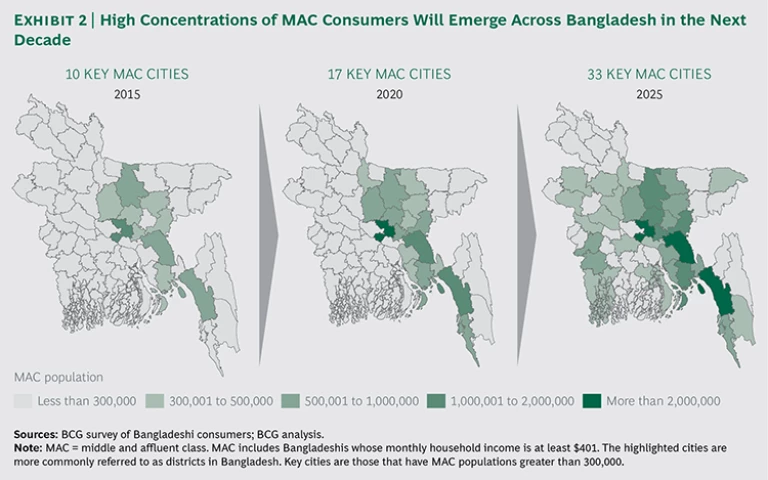

At the same time, buying power will quickly spread through more of the country. Currently, around 80 percent of Bangladesh’s MAC population is concentrated in two cities—Dhaka and the eastern port city of Chittagong. We see the dispersion of wealth unfolding in two waves. In the first wave, most of the MAC population growth will occur in Dhaka and Chittagong and will begin to take off in smaller cities in the eastern half of Bangladesh. This development will have significant implications for business. For the next few years, consumer product companies will need to focus on scaling up their operations and service capabilities in Dhaka and Chittagong to meet surging demand and to attain economies of scale.

In the second wave, major concentrations of buying power will emerge in other places across most of the country. The MAC population will more than double in Dhaka over the next decade, and it will more than triple by 2025 in Rajshahi, an industrial center in North Bengal, and in Barisal, a southern port city. We project that the MAC population will increase sixfold in Khulna, an important, fast-growing industrial hub in southwest Bangladesh. In all, we project that by 2025, compared with only 36 today, 61 cities in Bangladesh will have MAC populations of 100,000 or more—a market big enough to be firmly on the radar of a global company. The number of cities with clusters of more than 300,000 such consumers will more than triple, to 33, by that time. (See Exhibit 2.) At first, growth will occur most rapidly in eastern cities such as Lakshmipur, Gazipur, and Brahmanbaria and then in such western cities as Jessore, Tangail, and Jhenaidah. This second wave of regional dispersion will require many companies to expand their infrastructure, distribution, financial management, and capabilities to many more cities in order to serve important new markets.

To capture the opportunities and establish a leadership position in Bangladesh, companies cannot simply transplant brand, product, and go-to-market strategies that have worked in other emerging markets. A number of traits differentiate the Bangladeshi consumer culture even from nearby Asian emerging markets. These traits are likely to influence purchasing priorities and preferences as households grow more prosperous. Even many multinational corporations with considerable emerging-market experience will need to treat Bangladesh as a new frontier.

Insights into Bangladeshi Consumer Attitudes

To construct a portrait of the rising Bangladeshi consumer, we used several methods. First, we analyzed how household consumption of a broad variety of goods and services changes as incomes rise. Second, we surveyed more than 2,000 Bangladeshi consumers, asking them about their sense of financial well-being, the factors that contribute to their purchasing decisions, their attitudes toward brands, and their purchasing plans and priorities.

Several traits stand out as distinctly Bangladeshi. The respondents expressed a high level of optimism and a willingness to spend that is tempered by wariness of debt. Other traits include a focus on family needs, strong brand affiliation, and a willingness to spend more for quality.

High Levels of Optimism. Our research found that Bangladeshi consumers are among the most optimistic in the world. Sixty percent of the consumers we surveyed reported that they expected their incomes to rise over the subsequent 12 months, a good indicator of their willingness to spend. This sentiment was strongest among MAC consumers, 71 percent of whom believe that their incomes will rise.

Bangladeshis are also optimistic about their country’s economic future. Seventy-nine percent agreed that their generation has a better life than their parents did, and 81 percent believe that the generation to come will live better than they do. This consumer optimism about the future is significantly higher than in other big emerging markets, including China, India, and Indonesia. It also contrasts sharply with sentiment in developed economies. In the U.S., for example, only 24 percent of consumers surveyed believe that the next generation will be better off. In the EU, just 18 percent agree, and in Japan, a mere 9 percent.

Consumer optimism translates into a strong desire to buy. Sixty-nine percent of respondents agreed with the statement, “It seems like every year, there are more things I want to buy.” This sentiment was significantly stronger in Bangladesh than it was in leading Southeast Asian economies, such as Indonesia, the Philippines, and Thailand, where we conducted similar surveys.

Wariness of Debt. Whether or not the strong intent to buy will translate into actual spending will largely depend on the accessibility of credit and whether households are confident that debt will not impose a serious financial burden. Around half of Bangladeshi consumers surveyed reported that they are concerned about their ability to repay their debts, and around two-thirds said that they believe that uncertainty about the local economy could affect their financial health.

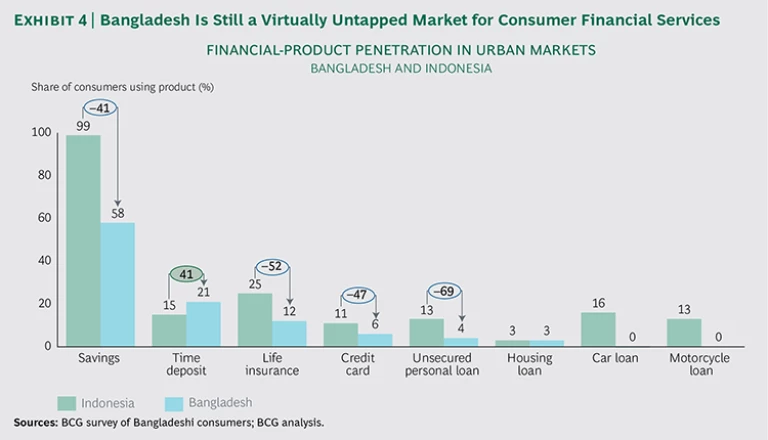

This concern about debt, which is significantly higher in Bangladesh than in such emerging economies as Indonesia and Thailand, could stem from a number of factors. One is that the consumer credit market is very underdeveloped in Bangladesh. Only 20 percent of MAC consumers surveyed—and 6 percent of all consumers—reported that they use credit cards. Only 3 percent of MAC respondents have home loans. The use of such debt instruments is far lower in Bangladesh than in developing economies such as Indonesia. Rather than secure loans from commercial banks, Bangladeshis tend to borrow from friends or from informal lenders, who charge high interest rates. Local cultural attitudes toward debt could also be a factor.

A Family Orientation. Bangladeshis focus more attention on the immediate needs of their large households, which average five members, than do consumers in many other emerging markets in Asia. Seventy-five percent of Bangladeshi consumers surveyed agreed with the statement, “I never spend money on myself until the needs of my family are met.” Among Southeast Asian consumers surveyed, only Filipinos identified more strongly with this sentiment. By contrast, 57 percent of Indonesians, 55 percent of Thais, and 38 percent of Burmese agreed that their family needs come first.

These findings indicate that companies should expect that the strongest growth will occur in categories that benefit the entire family. A refrigerator would take priority over an Apple iPhone, for example. Companies should keep this strong family focus in mind when they determine the mix of products, retail channels, and marketing-communications strategies they deploy in Bangladesh.

Strong Brand Identification. There are great opportunities for brands in Bangladesh, according to our research. Bangladeshi consumers cited brand as the leading factor they consider when purchasing a product, followed closely by price and then quality. Factors such as impact on health, convenience, discounts and offers, and social status ranked low as priorities.

Brand loyalty is most important in the consumer durables category: more than 80 percent of respondents cited brand as their top priority when making a purchase. Around 60 percent identified both brand and quality as factors in buying personal-care items, household care products, and packaged food and beverages.

These findings suggest that, as many are first-time buyers in some product categories, Bangladeshi consumers want known brands because they feel that they can be sure of their quality and reliability. Our research also found a strong preference for imported personal-care products over local brands, especially among MAC households.

A Willingness to Pay for Good Quality. Although our research found that consumers want to work within a budget, it also found that they are willing to spend more if that means that they are getting better quality for the product categories that matter most to them. Bangladeshis are also less likely to be influenced by discounts and promotions than consumers in most other emerging economies.

Only 38 percent of Bangladeshi respondents agreed with the statement, “I enjoy hunting for the best deals, discounts, and promotions.” That compares with 53 to 76 percent who agreed in Myanmar, Thailand, Indonesia, Vietnam, and the Philippines.

The Key Opportunities for Consumer Product Companies

The rapid rise of MAC families will provide a major new growth market in the coming decade for providers of a broad variety of goods and services. Millions of households are approaching an income level that will allow them to move beyond basic necessities to purchase more goods and services that offer convenience, comfort, and luxury.

But the opportunities will vary by product category. Companies in some categories should prepare for sales to take off in the near term, while in other product categories, companies should be preparing the ground for a future push. The strongest opportunities will be in product categories in which Bangladeshi households trade up to goods and services that offer greater convenience and luxury but also meet the needs and budgets of families. Companies should develop strategies around the shopping habits of Bangladeshi consumers, who still purchase the vast majority of fast-moving consumer goods through traditional retail channels but are also rapidly embracing the mobile Internet as a shopping tool. Our analysis revealed three general traits of Bangladeshi consumer behavior.

A Growing Desire to Trade Up. An analysis of consumer takeoff curves for consumer durables in Bangladesh illustrates that, as their incomes rise, consumers tend to trade up to products that offer greater convenience and comfort. By the time consumers attain the aspirant monthly household income of at least $151, around 80 percent already own a color TV, and more than 90 percent have a basic mobile phone.

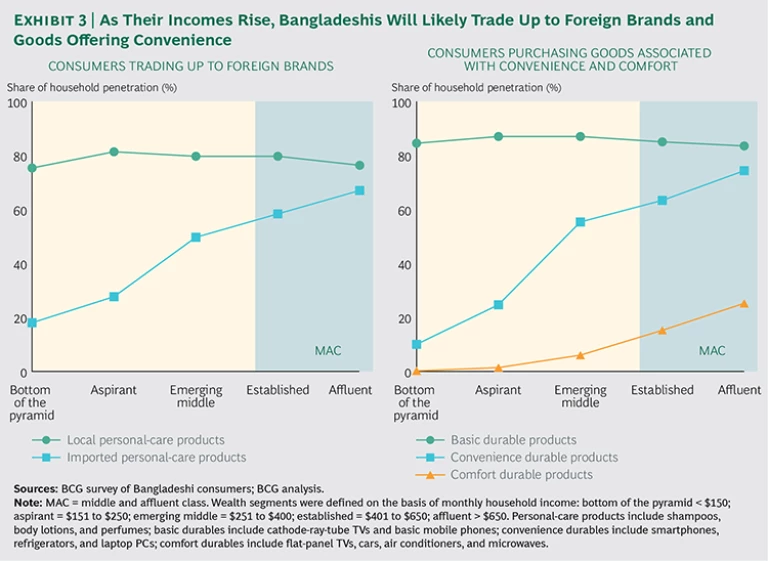

Consumers’ purchases of appliances that offer more convenience, such as refrigerators and smartphones, accelerate as their incomes rise. Consumption of goods offering more comfort and enjoyment tends to take off as households enter the established middle class. This is particularly true for durables such as air conditioners, flat-panel TVs, automobiles, and microwaves (See Exhibit 3.)

Ownership of such items is relatively low, at around 5 to 10 percent of households, until the income of average Bangladeshi households reaches the emerging-middle level of at least $251 a month.

Trading up is particularly pronounced in wireless telecommunications. Our research found that the market penetration of smartphones in Bangladesh leaps from 25 percent of households among aspirant consumers to around 60 percent among emerging-middle consumers. Use of basic mobile phones—which is virtually universal among those at the bottom of the pyramid—declines as household income rises.

Companies that can win brand loyalty in packaged-food, personal-care, and home care products can also anticipate strong growth as Bangladeshi consumers trade up. Average monthly household spending on fresh produce rises by 14 percent when household income reaches the established bracket, but it leaps by 53 percent, to around $103 a month, when it comes to packaged foods. When consumers pass the established threshold, spending on personal-care items jumps by 40 percent, on home-cleaning products by 68 percent, and on floor- and toilet-cleaning products by 104 percent. This shift in purchasing behavior suggests that Bangladeshi consumers spend more to keep up their homes as their living conditions improve.

International brands stand to benefit most from the growth of Bangladesh’s MAC population. Around 35 percent of established and 45 percent of affluent households purchase imported beauty products, for example. Consumption of imported creams increases by more than half, and imported shampoos by more than 60 percent, when households enter the established bracket. Still, Bangladeshi households tend to buy entry-level foreign-brand products priced at $10 to $60. Purchases of more expensive, higher-end imported products remain modest even among the affluent.

In some major product categories, the Bangladeshi market has barely been tapped. One such category is financial services. As mentioned above, very few Bangladeshis use credit cards or take out loans to purchase homes or automobiles. Penetration is also relatively low in other basic consumer financial products. Comparisons with Indonesia are enlightening. Only 58 percent of Bangladeshi consumers we surveyed have savings accounts, compared with 99 percent of Indonesians. Just 12 percent have life insurance policies, compared with 25 percent of Indonesians. (See Exhibit 4.) This indicates that for companies that can offer affordable terms and can establish themselves as trustworthy, there are potentially huge untapped opportunities in Bangladesh for consumer financial products—especially as households enter the market for big-ticket items such as cars, larger homes, and major appliances that require financing.

A Heavy Reliance on Traditional Channels. Although our research shows that Bangladeshi consumers increasingly use modern retail outlets such as convenience stores and supermarkets as they gain wealth, they still overwhelmingly do most of their everyday shopping in traditional channels. The most prominent format is the mudir dokan, Bengali for a mom-and-pop shop. The typical mudir dokan consists of a merchant selling products over a counter. Buyers have little opportunity to comparison shop: brand options are limited, prices are not well displayed, and visitors cannot browse the outlet.

Around 94 percent of MAC households in Bangladesh report that they still do most of their grocery shopping at traditional retail outlets. That compares with 76 percent in Myanmar, 77 percent in the Philippines, and only 27 percent in Thailand. MAC households also purchase more than 80 percent of their home-care and personal-care products at such shops.

Modern retail channels are likely to become more important as they become more available and closer to the country’s growing concentrations of MAC households. MAC consumers purchase 87 percent more packaged goods from supermarkets and 110 percent more from convenience stores than do consumers in lower-income segments. But such modern channels still account for a small portion of purchases. For the foreseeable future, therefore, getting more of their products onto the shelves of mudir dokan shops will be a necessity for companies hoping to boost their share of the Bangladeshi market.

High Engagement Through the Mobile Internet. In Bangladesh, consumers are rapidly embracing digital technologies—particularly the mobile Internet—as tools for shopping. Since third-generation (3G) wireless services were launched there in late 2013, consumers have adopted smartphones and high-speed mobile services at a breakneck pace. Some 41 percent of all urban consumers surveyed—and 68 percent of urban MAC households—have smartphones. By comparison, 43 percent of MAC households and 9 percent of lower-income households own laptop PCs. What’s more, Bangladesh is still at an early stage of adoption. Because of the growing availability of inexpensive smartphones, we anticipate that Bangladeshi consumers will switch to high-speed mobile services at a much faster pace than did consumers in most other Asian developing economies when 3G or 4G networks became widely available.

The widespread use of high-speed mobile Internet services will have significant implications for companies, which will need to quickly deploy mobile-centric e-commerce strategies. Bangladeshi consumers will increasingly engage with companies and brands through their handsets. Indeed, for many households, the smartphone will be the first—and, in many cases, the only—portal into the Internet. Because many consumers who currently make all of their purchases in cash will make the leap directly to mobile transactions, companies will need to set up e-payment systems tailored to mobile.

Our research found also that Bangladeshi subscribers use their devices to guide their shopping decisions. Among consumers we surveyed who use the Internet, 66 percent said that they search for product information online, 54 percent visit company websites and Facebook pages, and 37 percent check social media.

Furthermore, Bangladeshis also place a remarkably high level of faith in the information they read on the Internet. Eighty-two percent of survey respondents said that they trust any online source of information—just slightly fewer than those who said that they trust the recommendations of friends and relatives—and 70 percent said that they trust official company websites for goods and services. Indeed, consumers indicated that they have much more trust in these sources than they do in online reviews (45 percent) and third-party websites (19 percent).

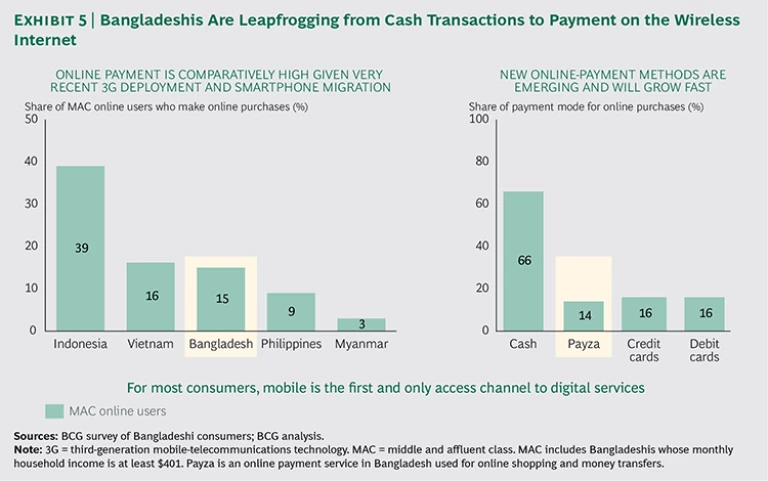

E-commerce remains nascent in Bangladesh, however. Only 15 percent of MAC households reported that they shop online, compared with 39 percent in Indonesia. Still, MAC consumers are twice as likely as lower-income consumers to purchase products online. As the incomes of households rise, therefore, it is likely that so will consumers’ preference for shopping online. Consumers in Bangladesh are also using diverse online-payment methods. For example, around 14 percent of online purchases—almost as many as those made with credit cards and debit cards—currently are conducted through Payza, an online payment service. (See Exhibit 5.) We expect that these alternative payment nodes will grow rapidly.

The findings indicate that the mobile Internet will become an increasingly powerful tool for engaging with Bangladeshi consumers and that companies should place a high priority on their mobile digital content and services.

The insights into consumer attitudes and consumption traits identified by our research should help guide companies in their approach to Bangladesh’s rapidly growing market of MAC households. Establishing a lasting competitive advantage and market leadership, however, will require much more than tactical adjustments. It will require a comprehensive strategy based on deep knowledge of Bangladeshi consumers, a scaled-up on-the-ground presence, and, for most companies, a transformation of their Bangladesh organization.

An Approach for Winning in Bangladesh

Bangladesh presents a rare opportunity for global consumer-product companies that act now. Not only does Bangladesh offer one of the world’s fastest-growing populations of MAC households, but also many Bangladeshis are entering the consumer class for the first time. Very few global companies saw this market coming, so market leadership is very much up for grabs. Brand loyalties, preferred retail channels, and purchasing methods have only just begun to evolve.

Our research has uncovered several distinct attitudes and cultural traits that companies must take into account if they are to be successful in the Bangladeshi market. Companies can alter consumer perceptions with smart communications, product positioning, and go-to-market strategies.

We believe that the key elements of an approach for winning in Bangladesh include the following imperatives:

- Stress quality. Even though their incomes may be low in terms of global standards, Bangladeshi consumers are willing to pay more to buy high-quality goods and services for their families. They are, however, also budget conscious. Companies must create a strong value-for-money proposition to win over Bangladeshi MAC households.

- Conquer the debt dilemma. Companies that can ease consumer anxieties related to personal debt will be able to unlock significant growth opportunities in Bangladesh. To the extent possible, companies should introduce consumer credit at affordable interest rates and educate customers on how to manage debt. Greater acceptance of commercial financial products will unleash massive pent-up demand for major appliances, motorcycles, and other big-ticket items.

- Establish your brand. The exceptionally high importance that Bangladeshis place on brands indicates that companies should start fighting now to establish their brands in the minds of consumers. Companies should also begin to build their brand presence in cities that currently do not have high concentrations of MAC households but are likely to have them in the future. Although today most MAC consumers say that they prefer foreign brands in certain categories, there are also big opportunities for local brands that meet consumer expectations for good quality and value. Brands that can win consumer loyalty now will be in a strong position to win in the future.

- Educate consumers. Some consumer sectors in Bangladesh are so underdeveloped that much of the MAC population remains unfamiliar with the available options. Indeed, most consumers don’t yet know the right questions to ask. Such product categories include financial services, health care, and education—categories that are well established in many other emerging markets. Companies should gain a deeper understanding of the demand for new goods and services that has been created in other economies with large MAC populations.

- Develop creative ways to serve traditional channels. Although Bangladeshi consumers will increasingly use modern retail outlets as they become available, companies must adapt to the reality that, for the foreseeable future, the vast majority of purchases of fast-moving consumer goods will occur in small mudir dokan shops. This presents a variety of logistical challenges. Even in big cities such as Dhaka, poor physical infrastructure makes it difficult to reach such shops. What’s more, mudir dokan shops stock very few items. Consumer product companies will need to develop complex distribution networks to push their products in small quantities across a very large number of mom-and-pop shops in remote locations across the country.

- Build mobile-centric digital platforms. Advanced mobile technologies are being rapidly adopted by MAC households and are likely to accelerate consumption. Dynamic new retail channels will emerge as consumers get savvier about curating product information through their smartphones and grow more comfortable with wireless payment. Companies should start building robust e-commerce platforms designed for interacting with consumers through small digital screens—rather than primarily through computer screens—as well as e-commerce fulfillment capabilities that can meet growing mobile-enabled demand.

For most companies, winning in Bangladesh’s rapidly growing consumer market will require not only a ramped-up presence. It will also require an entirely new approach that is based on deep insights into Bangladesh’s MAC consumers and a transformation of their organizations. Companies that move now to get into position have an opportunity to build a sustainable competitive advantage in one of the world’s next important growth markets.

Acknowledgments

This report would not have been possible without the contributions of LightCastle Partners, Puja Agarwal, and Sadat Reza.