Thinking big isn’t always the best approach. In developing economies, including some very large markets such as India and China, targeting small market segments can be a more successful strategy.

In April 2014, we described a strategy we call street-smart sales, which allows companies to arm local sales managers and representatives with new geoanalytical tools and the authority to create compelling offerings for customers in small market segments. The payoff can be considerable. Even in markets where growth is tapering, companies have consistently demonstrated revenue gains of 5 to 8 percent by following this approach. (See “ Going to Market in Developing Economies: Winning Big by Targeting Small ,” BCG article, April 2014.)

Despite India’s extraordinary diversity, marketers have historically employed a broad-brush geographic approach based on zones and regions as their principal means of bringing products and services to market. But maps and demographic data are blunt tools. As income levels rise and companies seek to increase penetration of branded products and services, the shortcomings of this approach become more pronounced.

The street-smart sales strategy, on the other hand, involves developing street-by-street insights. It aims to get inside India’s countless neighborhoods and determine what types of people live in each one, who visits every day for work or other purposes, what they are likely to buy and why, and how well their needs are being met. This kind of analysis is a big challenge, but as we observed in our previous article, if it were easy and obvious, marketers would have adopted it long ago. Fortunately, a powerful new tool—street-level segmentation—makes targeting market segments at a street-by-street level not only possible but much easier and potentially highly profitable.

Diversity Dominates

India is defined by its diversity. More than 400 cities have populations of 100,000 or more. Their neighborhoods are populated by people with a great range of incomes, livelihoods, and social and cultural backgrounds. And across the country, some 1.2 billion people speak 22 languages, belong to six ethnic groups, and practice seven major religions.

India’s size and growth make it attractive. Annual GDP growth has averaged more than 6 percent over the last ten years. Average household income is likely to triple over the next decade, while consumption will increase 3.6 times by 2020.

Income and expenditure patterns vary widely across consumer segments, however. This economic diversity, combined with the population’s mix of social and cultural identities, presents complex challenges to marketers. Moreover, with few large national, or even regional, retail chains, merchandising in India tends to be a localized business—a big challenge for manufacturers and marketers, both local and international.

Identifying the Right Cities to Target

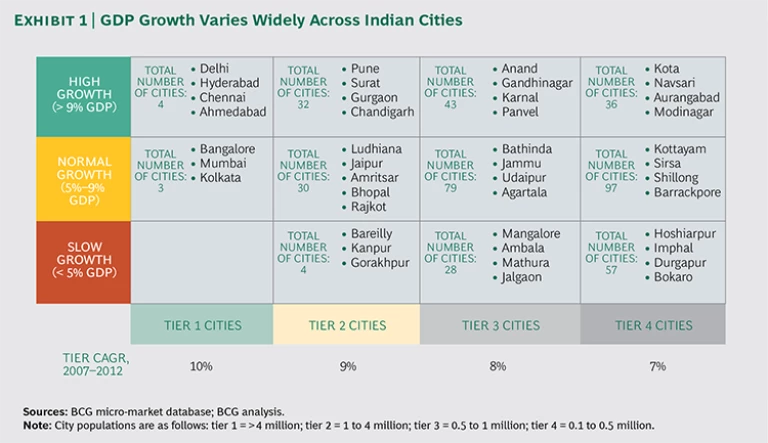

Marketers have historically approached India as a group of four zones that correspond roughly with income level: the high-income south, middle-income north and west, and low-income east. They have also concentrated their efforts on affluent and highly populated markets in India’s major metropolitan centers (those with populations of more than 1 million) and tier 1 cities (populations of 100,000 or more). These broad approaches have several shortcomings. One, of course, is that income levels and economic growth patterns vary substantially within each geographic zone. In the eastern zone, for example, the state of Bihar’s economy grew at an annual rate of 16 percent from 2010 to 2014, whereas Chhattisgarh’s GDP grew at 10 percent a year. Even within states, income levels and growth rates differ enormously by city, making it difficult for companies to know where to focus their resources. (See Exhibit 1.)

Second, people move and demographics shift. In some of India’s largest cities, for example, such as Delhi and Mumbai, infrastructure constraints and other factors have caused population growth to stabilize, while growth in smaller cities and towns is accelerating. Income levels and demographics also change over time. For example, from 1998 to 2005, manufacturing employment increased 41 percent in towns and villages near metropolitan areas, while manufacturing employment in urban centers shrank by 16 percent. These shifts have fueled income growth and purchasing power in many smaller cities and towns. These dynamics mean that for marketers, conventional measures such as zone-based economic indicators, population size, and citywide income levels have never been that effective at identifying high-potential markets. Today, other metrics are available, such as luxury car and smartphone sales, that are often more telling. For example, targeting affluent consumers in a city such as Ludhiana (population 1.4 million) can be more productive than targeting such consumers in much larger Jaipur (population 2.3 million). Even though Ludhiana is smaller than Jaipur, the number of luxury cars sold there is higher, indicating that more of its wealthy consumers are willing to spend. Similarly, for businesses targeting Internet-savvy consumers, analysis of smartphone sales and penetration suggests that a city such as Agra (population 1.3 million) is of greater interest than Kanpur, which has twice the population, because smartphone sales in Agra are much higher.

Street-Level Segmentation

Within individual cities, marketers have traditionally focused on either “catchment areas” or “neighborhood areas.” The former have clusters of shops or a high street that attracts visitors and consumers, while the latter surround a local institution—such as a church, temple, school, or community center—frequented by residents.

A market segmented according to the street-level strategy is much more precise: it is a single area, typically about 2 or 3 square kilometers in size, with a demographically and economically homogeneous population. It may contain no catchment and neighborhood areas, or it may contain several. Most cities can be divided into myriad such street-segmented markets, each exhibiting its own characteristics.

Street-segmented markets generally fall into three categories: work-intensive areas that consist primarily of commercial and industrial facilities, residential-intensive areas that contain mostly housing, and shopping-intensive areas with a heavy retail presence. Within each type of market are concentrations of residents, regular visitors, or employees of interest to particular companies. A marketer of premium goods—fashion or high-end electronics, for example—will find a street-segmented market of high-income residents attractive. A company targeting younger consumers may be intrigued by a concentration of cafés, bars, and restaurants. Companies that cater to workers, such as restaurant chains and transportation businesses, will find work-intensive areas the most promising.

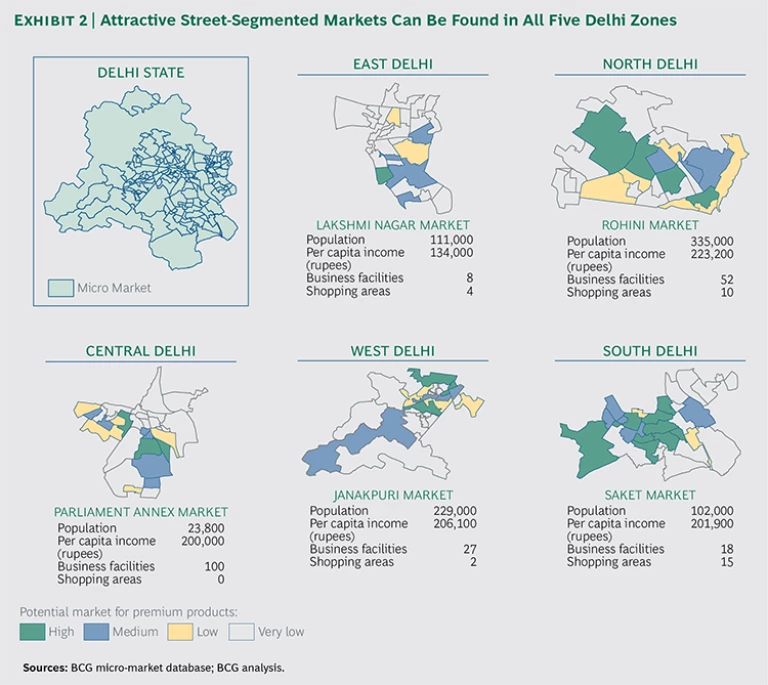

Take Delhi as an example. (See Exhibit 2.) This city of some 10 million people can be divided into five geographic zones. Traditionally, marketers have considered south and central Delhi the preferred areas to target high-income consumers; the south zone, for example, includes seven residential-intensive markets—such as greater Kailash, Saket, and Hauz Khas—where affluent consumers live. Using street-level segmentation, however, we can identify markets in east and north Delhi that are of equal or greater attractiveness than the south and central zones. In east Delhi, these areas include Lakshmi Nagar and Preet Vihar; Rohini and Shalimar Bagh are similar areas in north Delhi.

Based on the results of street-level segmentation, a company can identify high-potential markets throughout Delhi and in many other cities as well. Gurgaon, for example, is a city that a company might have overlooked in the past because a broad-brush catchment- or neighborhood-based analysis would not have uncovered its attractive pockets of consumers.

The Big Potential of Small Segments

Street-level segmentation has at least four advantages over more traditional approaches. First, companies can identify high-potential markets wherever they exist, rather than approaching each city as one large, homogenous market, and, as a result, wasting human and financial resources. For example, most marketers would not consider Panchkula, Ludhiana, Amritsar, and Surat top priorities. But each has street-level markets that place in the top 20 in India based on household income. Faridabad is another example. Although it is ranked only twenty-first nationwide for affluence, Faridabad has five street-level segments in which two-thirds of households have annual incomes of 1 million rupees (about $17,000) or more. This kind of analysis allows marketers to apply their resources to attractive street-level segments in multiple cities rather than saturating one or two large cities completely—and inefficiently.

Second, street-level segmentation facilitates more precise identification of target groups. It can help companies determine where potential customers live, shop, and work, which can aid in creating more accurate retail and distribution strategies. Segmentation also helps in assessing demand at the micro level by addressing not only target customers’ ability to buy (based on income levels) but also their propensity to buy (based on sales of comparable products). This microlevel analysis makes for more efficient management of demand planning, inventory, marketing and communications, and sales force assignment and incentives.

Third, street-level segmentation allows companies to distinguish highly competitive areas from those where competition is less intense. They can identify the strongest competitors in any given area and assess the commitment and strategy of each based on data from other markets. The segmentation approach also helps companies identify “white spaces,” areas with high potential and low competitive intensity. Late entrants looking for a foothold or companies looking to expand in an already saturated city may find this information especially useful.

Fourth, companies can use the approach to scrutinize the changing city landscape and identify promising areas to establish a foothold ahead of competitors. Street-level segmentation can also have a tangible impact on business development costs, particularly real estate. For instance, using street-level analysis, a mobile-phone marketer compared two small markets in Delhi and found that while both had similar sales potential, rents in one were three to four times higher than in the other.

Multiple Applications for Many Businesses

Street-level segmentation has applications for many different kinds of businesses and business functions.

Sales Force Optimization. Companies can allocate sales territories on a street-level basis, aligning targets with each territory’s potential and assigning relevant and achievable targets to sales representatives. Street-level segmentation also helps ensure efficient routing and use of resources.

Demand Planning. Companies can calculate the market potential (both current and latent demand) of a street-level market by using relevant proxies such as per capita income, household earnings, number of schools, number of corporate offices, and neighborhood attractions, such as cafés, restaurants, or other gathering spots. In network planning, for example, telecommunications companies can analyze metrics such as population, income level, and Internet usage in a particular area to estimate the size of the subscriber base and its use of specific services, enabling better projections of the number of base transceiver stations needed. One large international mobile-handset manufacturer, looking to establish a retail network in India, used street-level segmentation to short-list attractive small markets in 150 cities, distilled from an initial list of 500. The company analyzed more than 20 parameters, including household earnings, luxury-car sales, and social-network usage, to calculate the potential of each street-level market.

Channel Mix. Companies can determine the channel mix (general trade versus modern trade versus luxury stores) at a street-segmented level much more precisely than at a citywide level.

Footprint Enhancement. Street-level segmentation can show companies where to open stores and how many would be needed in order to penetrate high-potential areas. For example, it can help banks estimate more precisely the number of branches and ATMs needed to cover a city. One bank, which sought to more than triple its network to 700 branches over three years, identified high-potential markets by mapping the banking landscape in 200 cities. It analyzed economic and demographic parameters and assigned each potential market to one of four categories: must-have, potential highly attractive, underpenetrated or high growth, or attractive commercial area.

Merchandising. Companies can decide which SKUs to push in different street-segmented markets based on much more accurate predictions of what is likely to sell. Similarly, they can vary in-store stock according to demand in different markets, using demographics (such as age and income levels) and behavioral characteristics (such as Internet usage and shopping habits) to determine which products are most relevant to target customers. An appliance company, for example, might sell less expensive, direct-cool refrigerators in areas with high population density and low per capita income and frost-free machines in more affluent areas.

Media Planning. Certain types of media may be more effective in some parts of a city than in others. Just as digital technology allows companies to send targeted ads to specific consumers, street-segmented data enables companies to plan below-the-line marketing efforts, such as coupons and in-store activations, in a highly informed manner in the off-line world. Not only does this improve targeting, it also helps measure the return on the company’s marketing investments more effectively.

India is only one of many emerging markets defined by diversity. Marketers that apply a one-size-fits-all approach in such countries waste resources and fail to reach their potential. Conversely, companies that think small, embracing diversity from a business perspective and turning local differences to their advantage, are likely to win big.