People in Senegal, Mali, Ivory Coast, and Madagascar can use a service called Orange Money to send and receive money through their mobile phones. Likewise, mobile phones can be used to pay insurance premiums in Ghana and Nigeria, to prepay for electricity in Rwanda, and to undertake debit card transactions in Zambia and South Africa. And practically everybody in Kenya who owns a mobile phone has heard of m-pesa, a mobile-phone-based money-transfer service that has thousands of agents around the country and is doing for people in Nairobi and the Kenyan countryside what a traditional bank’s ATMs do for people in the developed world.

All of this activity might suggest that mobile financial services, which are embryonic in most parts of the world, have become a mature market on the African continent, particularly in sub-Saharan Africa. That’s not quite true. Although there has been a surge of mobile-money use in sub-Saharan Africa—a surge that has generated a lot of interest and prompted us to write this report—even in this region, mobile-money services are really just getting started.

Further, as is the case with all high-potential new markets, too many vendors are competing for what is still a small pie; almost certainly, many of these vendors will not survive. (For an overview of the two main types of mobile financial services, see the sidebar “Mobile Bank Accounts Versus Mobile Wallets.”)

MOBILE BANK ACCOUNTS VERSUS MOBILE WALLETS

People often talk about mobile financial services as a uniform offering. In fact, there are typically two offerings that get lumped into the category of mobile financial services: mobile bank accounts and mobile-money solutions (also known as mobile wallets).

Mobile bank accounts are subject to national banking regulations, meaning, among other things, that there is deposit insurance and that the provider must be able to verify the identity of its customers (through the know-your-customer regulations that are increasingly relied on worldwide to prevent fraud, money laundering, and terrorist financing). Mobile bank accounts are designed to tie into banks’ back-office systems, and the technology supporting them is complex.

Mobile-wallet solutions are simple transaction systems that are usually based on mobile billing systems—the same systems that allow mobile users to add airtime or increase their data allowance. This less complex technical solution is not subject to national banking regulations, is often not interoperable (in terms of money transfers between different MNOs), and does not include deposit insurance. In addition, owing to the high amount of prepaid mobile-phone use in sub-Saharan Africa, MNOs usually don’t know who their customers are.

As mobile financial services become more deeply embedded in the lives of sub-Saharan Africans, it’s likely that regulators will start paying closer attention. In fact, that process has already begun. Consequently, it probably makes sense, over the long run, to build a system that has the flexibility to comply with banking regulations.

Mobile Financial Services in Africa Today—and Tomorrow

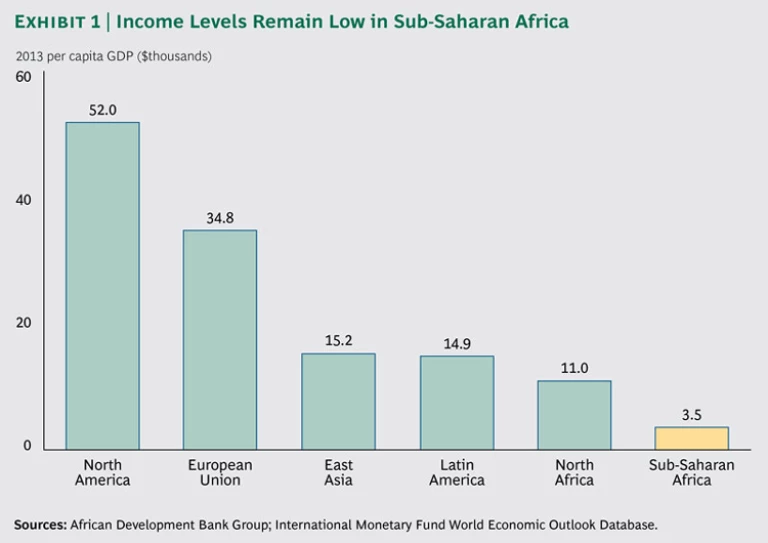

In general, the market for banking in sub-Saharan Africa has developed slowly. The majority of people in sub-Saharan Africa (as many as three in every four) are still unbanked, meaning that their experience with formal financial institutions is at best very limited. This is understandable in a part of the world where, in many cases, people earn the equivalent of $3 or less a day. Today, sub-Saharan Africa remains one of the world’s least-developed regions economically, with less than a quarter of the purchasing power of people in East Asia and about a tenth of the purchasing power of people in Europe. (See Exhibit 1.)

But although the exact shape of the market remains to be determined, African banks and mobile-network operators (MNOs) cannot afford to ignore mobile financial services.

In Africa, mobile financial services won’t primarily be an add-on used by an already “banked” population; rather, for most Africans, taking the mobile route will be their first experience with formal financial services. Indeed, for the many people who are “unbanked” in sub-Saharan Africa or are using only informal financial services, a mobile financial service may be their main means of accessing formal banking services for years to come.

A bank or MNO that isn’t active in the mobile-financial-service market runs the risk of becoming less and less relevant and of failing to capture the long-term value that would come from business model innovation. (For a perspective on the importance of this area, see “ Driving Growth with Business Model Innovation ,” BCG article, October 2014.)

Partly because of their lack of experience with traditional banks, many African consumers feel more comfortable with informal financial services. For instance, of the 40 percent of sub-Saharan Africans who say they save money, about half do so through savings clubs, which go by different names in different countries (stokvels in South Africa, tontines in Senegal and Ivory Coast, and chilimba, metshelo, or chama in much of east Africa). Almost all of the sub-Saharan Africans who have loans have gotten them through friends or family. The equivalent of roughly $1 billion in remittances flows out of South Africa to other countries in the Southern African Development Community annually—with more than $650 million of that reaching recipients through informal channels, such as private agents or family and friends traveling between locations. That is a lot of bills to count out in villages in Zimbabwe, Malawi, and Swaziland.

Rise in the Number of Bankable Sub-Saharan Africans

Sub-Saharan Africans have many reasons to move away from these informal approaches, which are often suboptimal from an economic or security perspective. For instance, using informal agents to transfer money is certainly riskier and more expensive than using a money transfer operator such as Western Union or Bank of Africa Group. Paper currency in Africa can also be very bulky—in some cases requiring more than 50 notes to equate to a single note in U.S. or European currency—making it inconvenient and risky to carry around. And it’s hard to see how Africans are going to avail themselves of the higher-quality goods and more comfortable lifestyles that they want without an alternative to cash and without something approaching a modern system of credit.

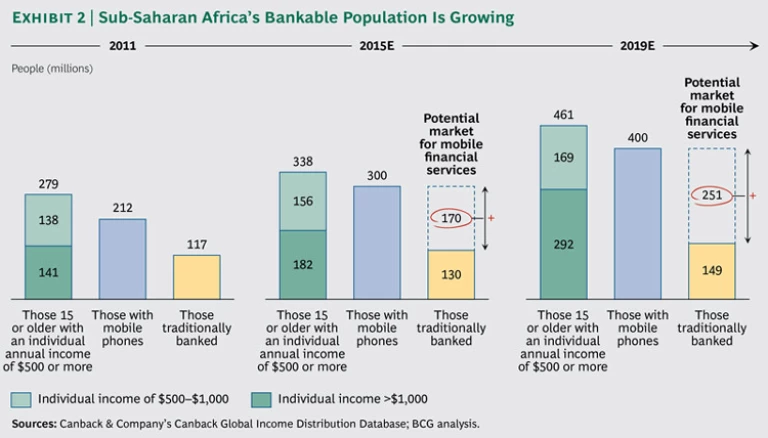

With the population in sub-Saharan Africa growing and becoming wealthier, the number of people aged 15 or older with an individual income of $500 or more per year will rise to more than 460 million in 2019. This trend is likely to strengthen as governments in sub-Saharan Africa increasingly focus on their education, health, and security systems—enhancing the state of well-being in their countries. (See Strategies for Improving Well-Being in Sub-Saharan Africa , BCG report, May 2013.)

According to The Boston Consulting Group’s estimates, there will also be some 400 million unique mobile-phone subscribers in 2019 and almost 150 million traditionally banked sub-Saharan Africans. (See Exhibit 2.) That will leave some 250 million people aged 15 or older who have an income of $500 or more and a mobile phone but no traditional bank account. This gives a sense of the potential market for mobile financial services.

High Levels of Mobile Penetration

Although sub-Saharan Africans do not have much exposure to formal financial services, they make extensive use of mobile technology. BCG’s analysis shows that more than half of all people in sub-Saharan Africa aged 15 or older have a mobile-phone subscription—more than twice the number of people who have an account at a formal financial institution.

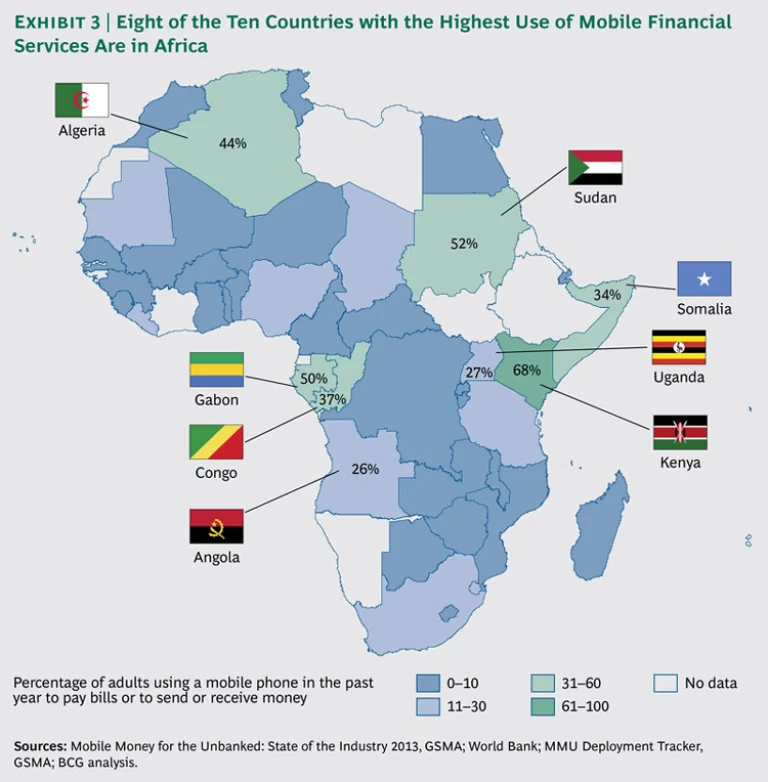

Considering their reliance on mobile phones and their lack of experience with formal financial institutions, it is probably no surprise that Africans are among the world’s most enthusiastic early adopters of mobile financial services. Eight of the ten countries that make the most use of mobile financial services are in Africa. (See Exhibit 3.) Use is particularly high in sub-Saharan Africa, which is the region with the highest number of registered mobile-financial-service accounts in the world (98 million as of 2012, compared with 36 million in the Middle East and North Africa; South Asia also had 36 million) and the highest proportion of active accounts (43 percent). Sub-Saharan Africa also has a far higher proportion of active accounts than other regions.

But when you look a little deeper, it becomes apparent that the mobile-financial-service market in Africa is not as advanced as some might think. Around the world, there are roughly 200 mobile-money services but only a dozen have more than 1 million users, and the mobile-money market in sub-Saharan Africa is equally fragmented. (The one exception is Kenya, where a unique set of circumstances has enabled m-pesa to reach critical mass and become the dominant service; see the sidebar “The Secret to M-Pesa’s Success.”) In most parts of sub-Saharan Africa, people pick from among a number of platforms, which are typically not interoperable (meaning that someone using one mobile wallet might not be able to send cash to someone using another, and vice versa) and which do not pay interest on, or guarantee, the money that is “deposited” in them.

THE SECRET TO M-PESA'S SUCCESS

It’s good to be smart. But it’s even better to be lucky.

M-pesa, the only breakaway success in Africa’s mobile-financial-service sector so far, had the incalculable advantage of government support. Early on, the Kenyan government said it would use m-pesa to make payments to Kenyan citizens, providing an alternative to a cumbersome system in which Kenyans had to cash government checks at the post office. And because m-pesa was going to benefit the Kenyan government directly, the government decided to remove one of the obstacles that might have impeded the service, allowing m-pesa to operate outside the provisions of banking law.

On top of what was effectively a birthright, Safaricom, the MNO that started m-pesa, made a smart call in turning remittances, which are hugely important in Kenya, into one of the first use cases outside of government payments. Safaricom also did a good job of building customer trust and adding agents that could sign people up for service all over the country.

As a result of these advantages, m-pesa has grown to serve 17 million customers—almost two in every five Kenyans use it. M-pesa’s revenue growth averaged more than 42 percent annually from 2010 through 2013; it now generates more than a quarter of a billion dollars in revenues per year.

M-pesa’s success has caught the attention of banks and mobile operators all over sub-Saharan Africa. But to see m-pesa as a template that can be applied elsewhere is to miss the special enablers of its success, especially the part played by a friendly government.

Indeed, at this point, m-pesa poses some risks to Kenya. The first risk is the sheer volume of payments flowing through the system—without the consumer protections that a true mobile-banking system would offer. And with so much of Kenya’s GDP now changing hands over m-pesa, government officials may understandably be concerned about the fact that m-pesa is partly a foreign entity. (In 2000, the UK company Vodaphone acquired a 40 percent stake in Safaricom.)

Safaricom tried to replicate the success of m-pesa in South Africa. But given the tougher regulatory environment there than in Kenya, the absence of any dedicated m-pesa agents, and the less advantageous remittance market, the original release of the service failed to take off. M-pesa hasn’t given up in South Africa; in mid-2014, it introduced a revamped version of the service that it hopes will be more successful.

Further, most of the services are led by MNOs and most of the transaction software is built atop MNO billing systems, meaning that the services lack the rudiments of mature banks’ transaction systems, including security, leaving them vulnerable to misuse and regulatory intervention as they reach more and more customers.

A $1.5 Billion Revenue Opportunity by 2019

For the moment, sub-Saharan Africans use mobile financial services to make payments. Generally, they are urban workers sending money back to family members in rural areas or people using their phones to purchase more airtime or to prepay for electricity or water in their homes. These basic payment activities will continue to account for most of the region’s mobile-money usage for the next few years. We estimate that in and of themselves, these payment activities—along with deposit income—could produce up to $1.5 billion in fees for mobile-financial-service providers in sub-Saharan Africa in 2019.

And other new sources of revenue are likely, as Africans look for more-efficient ways to handle their financial transactions. Microloans are a good example of an area in which a mobile financial service could position itself as a trusted alternative, especially in places where the best current option is a local informal moneylender. Savings are another area of promise, with the selling point being the ease—and security—of being able to save by keying in a few commands on a mobile phone versus depositing money with a stokvel, tontine, or chilimba. Some sub-Saharan Africans don’t even use these community-based savings vehicles; they just keep any extra money they may have in their homes, under the proverbial mattress.

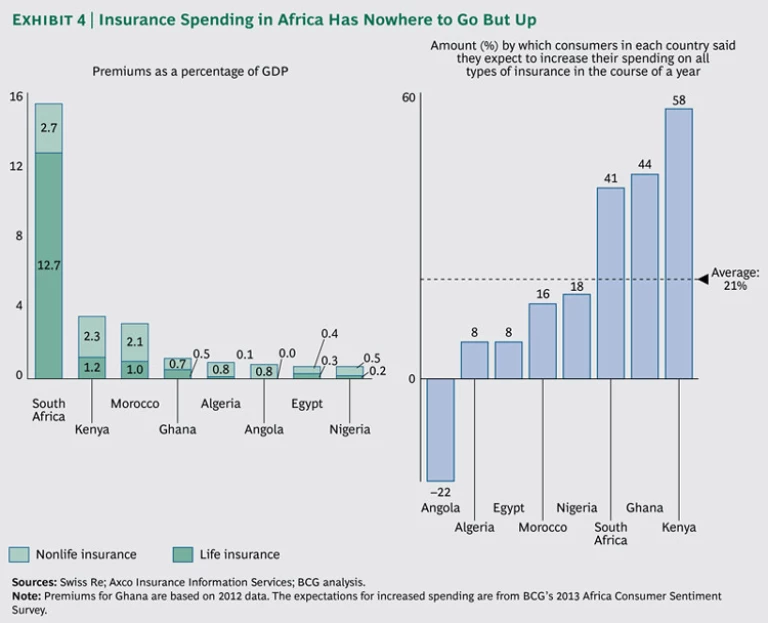

As Africans’ incomes increase, there will also be opportunities to give them access to other financial products, such as mortgages and insurance. People in Africa have traditionally spent very little on insurance, but that may be changing; a recent survey by BCG showed that Africans planned to increase their spending on insurance by an average of 21 percent in the ensuing 12 months; Ghanaians and Kenyans planned to increase their insurance spending by considerably more. (See Exhibit 4.) (For more information, see Understanding Consumers in the “Many Africas” BCG Focus, March 2014.)

Compulsory auto insurance is one reason for the increase, but some Africans are starting to see the benefits of other forms of insurance. Express Life in Ghana, which was bought in 2013 by UK insurance giant Prudential Financial, gives Ghanaians access to health and life insurance as well as funeral coverage. The premiums can be as low as 2.6 Ghanaian cedi per month (about 70 U.S. cents), and many customers pay the premiums using their mobile phones.

Then there is the opportunity to mine transactional data. As mobile financial services are more widely adopted, they will generate a significant amount of data that will be of use to financial institutions. The activity logs of hundreds of thousands of users in a given African country can be mined—using big data techniques—to understand what these users do with their mobile financial services and what other services they might be interested in. Financial companies can use the information that’s generated in their core processes or sell it to third parties such as credit bureaus, provided that they stay within privacy laws.

Another industry segment that could benefit from the rise of mobile financial services is retail. Daily shopping in Africa is mostly done through cash transactions at street markets and kiosks; the owners of these mom-and-pop shops end up carrying a lot of cash—and being vulnerable to theft. The driver of a truck that distributes soft drinks or confectionery products to African markets may likewise end up with a lot of cash and the same vulnerability. If these transactions could be done using a mobile financial service, the security risk would drop significantly. Mobile financial services could likewise help manufacturers of fast-moving consumer goods—and the larger retail chains that are starting to enter the African market—get a better handle on cash management and on their working capital.

How to Win in an Era of Mobile Money

The question for the next three to five years isn’t whether there will be an opportunity for banks and MNOs in mobile financial services; rather, the question is how to capture it. To succeed, companies must make ongoing investments in three areas: infrastructure, business capabilities, and governance.

Infrastructure

The transaction system for a mobile financial service must have several characteristics. It must be low cost. It must be modular so that future changes can be accommodated. It must be compliant with minimal financial regulations (reducing the likelihood that future overhauls will be required), and it must be interoperable with other transaction-processing systems and payment platforms. Today, neither the typical MNO billing system nor the typical core banking system meets all of these requirements—the MNO billing systems are too inflexible, and the banking systems are too expensive.

The second essential infrastructure component is secure communications. No consumer will use a system that might leave him vulnerable to losses or fraud.

Among communications protocols, SMS is the least secure and USSD is somewhat more secure.

The third essential infrastructure component is a network of agents. These are the physical places where customers can sign up for a mobile financial service and put cash into their accounts or take it out. Without these agents, a mobile financial service has no more chance of being heavily used than does a highway with no on-ramps.

The most obvious starting point for banks and MNOs is to have their existing branches or stores double as mobile-money agents. Generally speaking, however, these outlets exist only in Africa’s larger cities, so independent agents, perhaps mobile-phone-store operators, will be needed to bring mobile bank offerings to rural areas. Even this is not a straightforward solution, however, because most mobile-phone-store operators in sub-Saharan Africa don’t keep a lot of cash on hand. Fundamentally, the challenge is to develop a sufficient number of local liquidity points—neither too few to provide coverage nor too many for the people running them to reach profitable scale. The tactical challenges include preventing fraud, equipping the agents with the necessary tools, and establishing some “super agents” that can provide liquidity to these more ubiquitous local agents. To succeed with this, companies will have to build out the network locally and institute a well-thought-out incentive structure.

Business Capabilities

To develop successful mobile financial services, banks and MNOs will need six capabilities.

Strategic Agility. Mobile financial services are new, and companies will need to make adjustments to their operating models and try various tactics to get the results they want. Among the areas in which strategic agility will be most important is the planning and management of the agent network, especially with respect to making individual-agent economics work. For example, one mobile-money operator in West Africa has set up a revenue-sharing model designed to be very generous initially, in order to give agents an incentive to sign up as many customers as possible. Once the service reaches critical mass, the operator plans to normalize those contractual arrangements.

Consumer Insights. This speaks to a bank’s or MNO’s ability to identify and develop the offerings that would matter most to consumers. For instance, in some parts of Africa, the use case that will drive adoption may be long-distance domestic remittances; in other markets, it may be added airtime or even church donations. Consumer insight means knowing which additional services to roll out and when.

Marketing and Customer Engagement. To be successful with mobile money in Africa, banks and MNOs need to get inside the heads of customers. Like consumers everywhere, Africans respond best—and are most likely to make word-of-mouth recommendations—when a product or service provides an easy-to-use, intuitive experience. In the case of mobile financial services, a certain amount of education is also necessary to ensure that customers trust the product and have the financial literacy to use it. More-conventional marketing tactics (such as offering free airtime when using a mobile service to add minutes) can coexist with the more-intrinsic offers derived from customer insights (like offering vouchers for customers’ favorite shops), helping to drive uptake.

Start-Up Mentality. The need for quick decision-making and course corrections will be one of the biggest challenges for many banks and MNOs, which tend to engage in top-down decision making and are not known for introducing new services quickly. Those characteristics mean it may be beneficial for the teams working on mobile financial services to be organizationally separate. Competition for banks and MNOs will come partly from venture-funded companies that already have a start-up mentality and speed to market as goals.

Simplicity-First Approach. Every phase of building a mobile financial service—from getting it off the ground, to adding and tweaking features once the offering is in the market, to adjusting to regulatory requirements—will bring additional complexity. This is natural and to some extent necessary.

However, complexity doesn’t always add value. Non-value-adding complexity (complicatedness) could come in many forms: in customer agreements that keep getting longer (and harder to understand), in approval and administrative processes that take too long, in data that needs to be entered multiple times or stored in multiple places, in an increase in the number of organization layers or reporting lines, and in key performance indicators that conflict with one another. Similarly, the economics of a mobile offering are potentially threatened when legacy systems or comprehensive core banking systems are used. Instead of wasting money and slowing development with interface complexities and unnecessary functionality, a separate and modular IT-architecture development should be used. Complicatedness must be minimized if the customer experience is to be simple and appealing and if the offering is to remain a low-cost service.

Regulatory and Risk Awareness. Banks typically put every prospective customer through the same rigorous identification process. With documentation hard to come by in Africa—many Africans, for instance, receive their salaries in cash—it makes sense for mobile financial services to take a more staggered approach to identifying customers. For example, they could accept low-transaction customers on the basis of almost any form of ID whereas other customers who meet a certain risk profile (those requesting a loan or doing a transaction of a level high enough to raise suspicions of money laundering) would be subject to full know-your-customer identity checks.

As more financial services are added to the platform, mobile-money operators will need to be able to use the information they have on customers’ mobile-money activities and from other sources to monitor and assess individual users’ creditworthiness. This ability to gauge risk is especially important in sub-Saharan Africa’s cash-driven economies because there is typically no easy, convenient way to gauge a customer’s ability to pay. At the back end of the credit business, efficient collection procedures—compliant with consumer protection and other regulatory legislation—are needed to recapture loans that are past due.

Credit risk is not the only type of risk that must be managed. Operational risk (which is connected to the stability of the service’s IT architecture and the scalability of its transaction processes), when not properly managed, can lead to customer-facing system downtime, payment delays, and failure to deliver on service promises (such as a 24-hour turnaround time on complaints).

Governance

Mobile financial services should not be a go-it-alone proposition, in our opinion. Neither banks nor MNOs on their own have everything that’s needed to succeed. The banks have the back-office systems and the understanding of financial-industry regulations; the MNOs have the access to consumers and the preexisting agent networks. When it comes to mobile financial services, banks and MNOs are complementary, each having something the other needs. In many cases, it will make sense for them to team up. To date, however, there have been very few partnerships of this sort.

Such partnerships, when they do come together, will require strong governance. The first area of governance involves overseeing the overall ecosystem. This means choosing the right partners by assessing capabilities and determining the best fit in terms of strategy, goals, and objectives. It means defining the legal and commercial nature of the partnership and setting up the partnership so that all parties have something to gain.

The second area of governance involves overseeing the partnership. Good governance of an individual partnership starts with a clear separation of responsibilities in order to minimize inefficiencies. It also involves making sure that long-term customer needs are prioritized over the near-term profit considerations of either party. In addition, the partnership should be arranged in such a way that both parties regard it as a long-term commitment. In practice, this is hard to enforce in a contract, so the careful selection of a partner in the first place is the most important element.

What’s at Stake and How to Proceed

In sub-Saharan Africa’s emerging economies, mobile financial services represent a significant new development. There is no single path that will be right for all banks and MNOs, but they certainly can’t wait for the market to unfold and for competitors’ strategies to solidify.

Banks

On the positive side, mobile financial services could allow African banks to capitalize on the trend toward financial inclusion and to start generating revenues from the tens of millions of Africans who have never used banking services before but may be in a position to do so as their incomes increase. Failure to develop a successful mobile-money offering could cause banks to miss this opportunity and could erode their existing customer bases as the banked population in Africa increasingly makes use of mobile money.

In building mobile financial offerings, most African banks aren’t starting from a strong position. Their current services are designed to derive profit from a base of wealthier Africans, not from those Africans who are ascending to banked status for the first time. And to the extent that they devise good mobile offerings and keep their existing banking customers in the fold, banks may end up replacing some more-profitable transactions with less-profitable ones.

Of course, cannibalization of this sort is something practically every industry occasionally experiences, with companies sacrificing one portion of their business when a new trend comes along. For instance, in the last few years, automakers BMW and Daimler have shifted their sales strategy to focus not just on selling cars but also on promoting car-sharing services, allowing drivers in some European cities to rent cars on an as-needed basis. In taking this tack, BMW and Daimler have acceded to a new market reality: that a segment of the driving population—particularly younger consumers—no longer wants to own automobiles.

It’s different with mobile financial services because some customers will have a hybrid profile: they will access banking services through both traditional brick-and-mortar banks and mobile services. But the basic principle is the same: it’s better to get some revenues than none at all, even if you have to develop a less expensive (and less profitable) version of what you sell.

In any event, it’s unlikely that many African banks can realize the full potential of mobile financial services operating on their own. Most banks don’t have a low-cost, secure communications infrastructure, and most lack the critical elements of an agent network. They have never had to serve the low-income, unbanked population segment and therefore don’t have a good understanding of what the segment needs. Some would probably even have a hard time entering into a partnership they did not clearly lead.

Some of these are capabilities that MNOs do have, so banks should consider partnering with MNOs. (Another option for a bank is to set itself up as a mobile virtual-network operator [MVNO] and try to enter the mobile-money market that way. The MVNO approach has limitations, however. See the sidebar “The MVNO Option.”) In a partnership with an MNO, a bank would naturally fall into certain roles—such as handling the banking license and regulatory reporting, maintaining the balance sheet, driving product development, and overseeing back-office functions. The nature of mobile services means that the interface to the customer would likely remain the domain of the MNO.

THE MVNO OPTION

In lieu of entering into a partnership with an MNO, some banks may want to turn themselves into “virtual” telecommunications companies and provide phone service themselves. Here’s a brief assessment of this option.

How It Works. The bank pays for the use of the MNO’s infrastructure.

Upside. The bank has full control of the service—it doesn’t need to negotiate details with any partner.

Downsides. This approach could be costly to implement, and the bank could face high switching costs. In addition, the bank might have to bear the full cost of developing the service itself and wouldn’t have the advantage of an MNO’s mobile-marketing know-how.

Conclusion. Without the help of an MNO, not many banks could attain the critical mass and scale needed to make the MVNO option work. They would be better off partnering.

As they move into mobile financial services, banks in sub-Saharan Africa must make a few overarching decisions. The first decision is whether to launch the service in a country where they already have a retail presence or to use the service as a vehicle for entering a market in a new location. A bank must also figure out what its innovation strategy will be: getting to the market first with a mobile financial service versus seeing what rivals offer and then trying to match or improve on it. For most banks (and for most MNOs), it will probably take several years to launch a product. (See the sidebar “From Green Light to Mature Offering: Four Phases and Several Years.”)

FROM GREEN LIGHT TO MATURE OFFERING

Four Phases and Several Years

Any bank or MNO that wants to offer a mobile financial service has to go through a four-phase process. Here’s a look at what must be accomplished along with the likely time frame for each. After each phase, the strategic choices regarding business model, governance, and infrastructure for the subsequent phase should be reviewed on the basis of market success, customer response, and economics achieved.

Phase One: Understanding Existing Capabilities. After a decision is made to build a mobile-financial-service solution, the company must make a realistic assessment of the capabilities it has versus the capabilities it will need. From there, it must decide how it is going to add the capabilities it doesn’t have—by developing them, acquiring them, or partnering. It is imperative to have a vision of the fully built product in this phase in order to reduce the risk of expensive and disruptive infrastructure overhauls in subsequent phases.

Duration: This phase will require two to four months.

Phase Two: Preparing the Payment Platform and Launching in the Market. Either on its own or with a key partner, the company builds and launches a fully functioning payment system that has the transaction and security pieces in place. Ideally, the design of the system allows for growth and is flexible enough to accommodate future regulatory requirements.

Duration: This phase will require 7 to 15 months.

Phase 3: Getting the Platform to Scale. The selection of the right use cases is critical to get users to try the service. This is also the stage at which the agent network must be developed and trained. And it’s the time to start teaming with other players—including, potentially, retailers, utilities, and the government.

Duration: This phase will require 12 to 18 months.

Phase 4: Opening the Platform to Other Financial Services. With a critical mass of users, other use cases can be added. Opening up the ecosystem will involve many additional partnerships. Third parties can be instrumental in offering lending, savings, insurance, and other financial services.

Duration: This phase is open-ended.

Another crucial decision for banks is how to build a mobile-financial-service business. They can base their approach on one of four organizational archetypes:

- They can develop the mobile financial service in-house, using their existing organization.

- They can develop a mobile financial service in a unit that is physically separate from the existing organization.

- They can fund the service’s development using a corporate-venture-capital or incubator model, making a decision later to bring the service back in-house, divest it, or continue to operate it as a partial shareholder.

- They can acquire an offering that has been developed externally and that is in an early stage of development or commercialization.

Every approach has its challenges and no single approach has proved infallible, but building the service outside the bank’s core organization, and as a separate business, has a lot to recommend it. Such a structure allows for faster decision making, offers a better chance of ensuring a low-cost mentality, reduces the chance of turf wars, and ensures that no one undermines the emphasis being placed (in many cases, for the first time) on a low-income customer segment.

MNOs

For MNOs, mobile financial services represent a chance to diversify their revenue streams and create a path into other areas, such as mobile music services and e-commerce. In this way, they can sidestep one of the risks that MNOs face in any market, including Africa: becoming mere data utilities or “bit pipes.” As data utilities, they would be vulnerable to price competition and to a superior way of transferring bits that might come along.

The good news for MNOs is that they—unlike banks—already have a lot of what’s required to put together a credible mobile-financial-service offering. For starters, they have the necessary secure, low-cost communications network. With the mobile outlets selling their service, they already have the beginnings of an agent network. They know how to market to Africans in the lower-income segment, because they are already doing it. They have good brands and a good understanding of consumers.

However, a few things are missing in the mobile-financial-service offerings that MNOs have introduced. Because these offerings are generally built on top of MNOs’ billing systems, they aren’t compliant with banking regulations. This is not an issue currently because these offerings are treated as mobile-wallet or mobile-money solutions—not as banking products with depositors. However, that will change as the amount of money in these services increases and as regulators take more notice of them.

For the moment, most MNOs seem to be treating mobile financial services as a secondary strategy—something they do to support their primary strategy of creating income from voice and data services. The rudimentary nature of most MNOs’ mobile financial offerings reinforces this impression. Further, most MNOs have opted to use their billing systems as the backbone for their mobile-money offerings rather than building separate systems—a decision that will prevent the offerings from developing into full-fledged financial services. And most MNOs have done nothing, so far, to make their mobile-money offerings interoperable with those of other MNOs.

No MNO in sub-Saharan Africa would erect a wall preventing its customers from placing voice calls to the customers of other networks; such a policy would lead to mass customer dissatisfaction. Yet such restrictions are the norm among the mobile-money services that have sprung up. On a short-term basis, this is understandable. The MNOs are probably patterning their mobile-wallet services after m-pesa, which has succeeded with a captive system that allows only m-pesa–to–m-pesa money transfers. But m-pesa is not an easily replicated model, for reasons already discussed. And on a long-term basis, having a closed system and treating mobile financial services as a secondary strategy are ill-advised ideas that will backfire.

MNOs may have more options than banks in terms of potential partners; their options include financial institutions and possibly third-party service providers. But they almost certainly need to partner, and they need to treat mobile financial services as a priority. (See the sidebar “How One Newcomer Is Making Waves” for a look at what both established banks and MNOs are facing competitively.)

HOW ONE NEWCOMER IS MAKING WAVES

Big banks and MNOs aren’t the only ones looking for a foothold in Africa’s emerging market for mobile financial services. Some newcomers have also stepped in. One of them is Take Your Money Everywhere (TYME), an operator of branchless banking solutions. In 2012, in partnership with the South African Bank of Athens, MTN (a mobile-network service), and Pick n Pay and Boxer Superstores (two South African retail chains), TYME introduced a simple system called Mobile Money. The system allows customers to send money, buy airtime and electricity, and deposit or withdraw cash at so-called till points maintained by the retailers.

TYME’s strategy is simple: anyone 16 or older can qualify for a basic account if they have an active cell-phone number just by keying in a valid South African ID. As of March 2014, Mobile Money already had 2 million customers, with an average balance of about 80 South African rand (roughly $7) in active customer accounts. TYME has put in place a tiered approach to meet regulators’ know-your-customer (KYC) requirements, with a lighter process for basic accounts and fuller KYC processes for customers looking to do more. Among the services that TYME is developing or considering are loan, insurance, and savings products and the enablement of cross-border remittances.

TYME partnered with a local investment company in Namibia and supported the development of EBank. EBank received its banking license in the spring of 2014 and is now in operation, with the goal of adding more Namibians to the country’s banked population.

Are TYME and the other mobile-financial-service start-ups that are beginning to operate in Africa friends or foes? To bigger banks and MNOs, they could be either. The only sure thing is that they are forces to be reckoned with and examples to learn from.

The Key Strategic Questions

As they start to stake out their positions in the market, banks and MNOs need to answer a few key questions.

For banks, the questions are as follows:

- Do we want to roll out mobile financial services in the markets we’re already in, or do we want to take the opportunity to target other countries in sub-Saharan Africa?

- Do we want to design a service that is innovative and stands out to consumers? Or would it be better to follow the lead of others in terms of product design and to innovate and try to create advantages for ourselves in other areas?

- Should we operate our mobile-financial-service unit as a stand-alone unit outside of the bank or house it within the core bank organization?

- With which companies should we look to partner for telecommunications and distribution?

For MNOs, the following questions are foremost:

- With which companies should we partner—traditional banks or nontraditional financial players including start-ups?

- Have we identified the use cases that will matter most in the countries we’re targeting?

- Does our product-development plan take into account the likely increased involvement of regulators?

- Should we pursue mobile financial services as an independent source of profits, or should we initially look at it as a driver of our telecommunications revenues?

- Does our long-term strategy include an emphasis on interoperability—that is, on allowing our customers to exchange money with customers of other mobile financial services?

It’s true that the current numbers are relatively small and that the shape of the market is still to be determined. But with the technology having arrived, with mobile penetration already deep and growing, and with a huge portion of the population approaching bankability, there is no question of the direction in which sub-Saharan Africa is heading. Before long, mobile financial services are going to be big in this part of the world. The vendors that want to establish a strong market position are going to need to find the right partners and develop an offering. Those things won’t happen in a few weeks; they will take months and in some cases longer. The time to begin is now.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the contributions of these BCG colleagues in putting together this report: Monique Baars, Alenka Grealish, Stefan Hoffmann, Klaus Kessler, and Robert Tucker. In addition, the authors acknowledge the contributions of those from organizations outside of BCG: Bruno Akpaka, John Campbell, Rolf Eichweber, Leslie Falvey, Costas Joannides, Huw Newton-Hill, Ilze Wagener, and Rosa Wang.