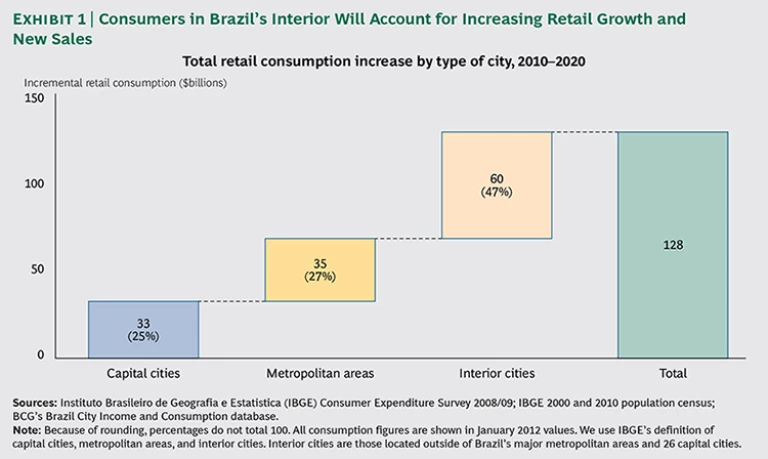

Concerned about the future, many Brazilian consumers are keeping a tighter hold on their wallets. Over the last 15 years, Brazil enjoyed a period of economic stability that fostered a strong consumer market. But the country’s economic growth is slowing—and with it, consumers’ appetite for spending. However, although consumption is projected to slow overall, Brazil’s interior cities are bucking the trend as demand growth moves inland. Through 2020, consumers in the interior regions are expected to account for more than 45 percent of growth in the retail sector, or $60 billion in new purchases. (Given the volatility of exchange rates, these numbers are approximate.) (See Exhibit 1.)

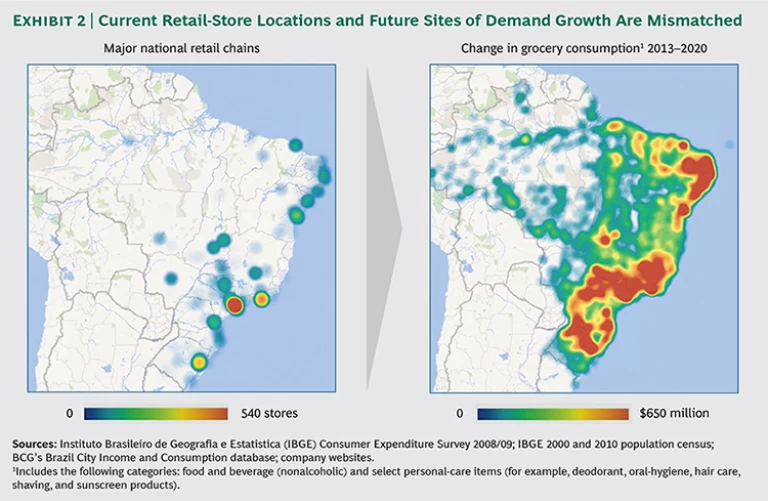

Yet few of the country’s retailers are prepared to capitalize on this growth opportunity, largely because they’ve focused their efforts almost exclusively on Brazil’s highly populated coastal cities. This mismatch between the location of current retail stores and the sites of future demand growth is striking. (See Exhibit 2.)

As consumption in today’s leading retail locations slows and consumer demand shifts to the interior, retailers must determine how to profitably reach those markets.

Recognizing the Challenges

Moving into Brazil’s interior presents a new set of challenges that can be difficult for retailers to address in a cost-effective manner. Because inland populations are less dense, consumer demand is more fragmented, making it difficult to reach the minimum thresholds that warrant the modern retail presence of branded stores (versus traditional mom-and-pop shops) seen in urban coastal areas. Distribution and logistics are also problematic. The interior is harder to reach and more costly to serve with the typical retail supply chain. Another obstacle is finding local store managers and sales reps with the necessary skills, knowledge, and education. Finally, many retailers lack an understanding of the buying patterns, preferences, and behaviors of consumers in Brazil’s interior, who spend differently from their urban counterparts even at the same income level.

Because of these four challenges—fragmented demand, high cost to serve, shortage of local talent, and lack of consumer understanding—most leading retailers have largely ignored Brazil’s inland regions. This was fine when demand was strong in the urban coastal areas, but with demand growth migrating inland, retailers must find ways to overcome these challenges.

Targeting the Interior

Although most major retailers have yet to target Brazil’s interior cities, some retailers are already winning market share and customer loyalty. Drawing on these success stories and our own work with the retail sector in Brazil and other global markets, we’ve identified five actions that can help retail companies in Brazil move strategically and profitably inland: mapping the landscape, developing new store formats, creating a multichannel strategy, rethinking operations, and building a local workforce.

Map the Landscape

In large metropolitan areas with high population density, retailers can analyze potential consumer demand by city or even by neighborhood. To address the problem of fragmented demand in the interior, however, companies must think in terms of clusters—that is, groups of cities that are relatively close to each other. Consumers in Brazil’s smaller interior cities often are willing to travel much farther for a product than their big-city peers. According to a leading apparel retailer in Brazil, interior consumers are willing to travel up to 20 miles (30 kilometers) to make a purchase. This willingness to travel varies by product category. Companies must understand how far buyers will travel for which product categories and view their “market” as the cities that fall within that radius.

At the same time, retail companies must identify the commercial hubs for each cluster. These hubs are the cities with businesses that serve the other cities in the cluster. For example, Ribeirão Preto in the interior of São Paulo state attracts traffic from neighboring towns. Although the city itself has only about 200,000 households, which account for approximately $4 billion in purchases per year, its relevance increases significantly when we include the neighboring cities for which it currently acts as a commercial hub: when cities within a 60-mile (100-kilometer) radius are included, the Ribeirão Preto cluster serves approximately 1 million households that account for more than $16 billion in purchases—not much less than Recife, the capital of Pernambuco. As a result, Ribeirão Preto attracts significant commerce; for instance, an Iguatemi shopping center opened there in September 2013.

Commercial hubs such as these are prime locations for new stores. Analytical tools such as The Boston Consulting Group’s Brazil City Income and Consumption database can estimate consumer demand for more than 200 product categories and identify clusters that meet certain thresholds of consumption so that companies can set priorities for expansion.

The next step in mapping the landscape is to assess the extent to which competitors are already meeting consumer demand in each cluster. One advantage of interior markets is the relative absence of competition. The apparel retailer Pernambucanas has set up more than 60 percent of its stores in the interior—the highest penetration of this area of Brazil among leading retailers in the sector. As a result, the company has far fewer competitors in its locations than other apparel retailers, which typically face four or more competing stores in most of their locations.

Develop New Store Formats

To profitably enter Brazil’s interior, companies must create a local presence in a cost-effective way. It may be necessary to try out different formats such as smaller, mobile, pop-up, and “virtual” stores.

Eletrozema tailors the size of its appliance stores to the size of the towns in which it operates; some stores are quite small and have only a few employees. All of the company’s stores operate more like showrooms, offering a limited selection of merchandise but making a wider assortment available online and through catalogs. (See "Eletrozema: A Home Appliances Empire Based in Brazil's Interior Cities.") Similarly, Magazine Luiza, Brazil’s second-largest appliance retailer, has large showrooms in select interior cities and “virtual stores” in smaller cities and poorer neighborhoods. The virtual stores have just a few small items (such as cell phones) on display but offer a greater variety of merchandise through online catalogs and provide a direct contact for shopping assistance. Many customers who have little or no experience with online shopping are likely to feel more comfortable in these stores than they would buying directly on the Internet.

Eletrozema A HOME APPLIANCES EMPIRE BASED IN BRAZIL'S INTERIOR CITIES

Eletrozema is Brazil’s ninth largest home-appliance retailer, with 7,000 employees, annual revenues of approximately $500 million, and double-digit growth. Almost 90 percent of its stores are in cities with fewer than 50,000 residents, and more than 90 percent are in the interior—the vast majority in the southeast. The company offers a wide range of products, from smartphones to cement mixers to chicken roasters, but focuses on traditional products instead of the “latest and greatest.”

Its stores are designed primarily as showrooms that feature select products, with a wider assortment available online and through catalogs, and products are delivered to customers’ homes. The stores are tailored to population density. The smallest format is less than 550 square feet (50 square meters) with just two employees in a town of 4,000 people. Eletrozema’s marketing budget is limited, and the company relies heavily on word of mouth.

Eletrozema has a breadth of categories similar to the bigger appliance retailers but focuses on popular, less expensive products rather than premium brands. The company’s storefronts and floor space tend to be smaller than those of the larger competitors, so displays are denser. Eletrozema seeks to hire local talent and trains managers in its local university.

Eletrozema’s success is due to several key factors. In addition to having strong management and cost controls, the company avoids direct competition from other appliance retailers by focusing on interior cities. Eletrozema offers financing on 60 percent of purchases and keeps default rates low by maintaining its own collections department. To build the trust of its customers, the company also offers free after-sales service—a rarity given that many manufacturer networks don’t reach the interior cities. The company also differentiates itself by offering free product assembly and generous installment plans with ten payments, compared with just four or five in competitors’ stores.

Some retailers focus on the customer experience by creating stores that are a form of entertainment shared with family and friends—and that become attractive destinations. Havan, a fast-growing apparel retailer, fuels its expansion in Brazil’s interior cities across the south, southeast, and midwest by building megastores on major highways. Besides offering a wide range of apparel, the stores have cinemas, food courts, and play areas for children. (See "Havan: A Destination Megastore.")

Havan A DESTINATION MEGASTORE

Havan has used aggressive marketing and branding to create a department store empire, and its huge stores, which offer a wide variety of products and activities, have become tourist attractions in their own right. Stores are concentrated in small and midsize cities in the south of Brazil. Almost 80 percent are in cities with fewer than 500,000 residents,; some are in cities with as few as 20,000 residents. Unlike the competition, which tends to focus on major cities and shopping malls, Havan sets up many of its stores on busy highways to capture passing traffic. On a fast track for growth, it has increased the number of its stores by 42 percent in 2013 alone. Customers often note the company’s strong local brand, and its billboard, radio, and TV ads are everywhere.

Shoppers with limited retail options in Brazil’s interior find Havan’s size and product variety—more than 100,000 items—to be major draws. In addition to offering products as diverse as apparel, tools, furniture, bedding, consumer electronics, camping equipment, and children’s toys, the company makes shopping a fun experience. Its smaller stores offer credit, free parking, a wedding registry, and free delivery of appliances, and its larger stores have additional features: food courts, cinemas, and play areas where children can be left for a reasonable fee while their parents shop. Other amenities include gift wrapping, travel services, and ATMs. Many even have a storefront replica of the Statue of Liberty with an observation platform. Unlike most other retail stores, which close at 6 p.m., Havan stays open until 8 or 9 p.m. on weekends and holidays. It also encourages employees to have fun at work.

Although not always the cheapest option, Havan offers reasonable prices on lower-end goods and keeps costs low with simple merchandising and displays. The company runs very few price promotions, instead using an “everyday low prices” strategy, with the occasional deep discount on a select item. In core categories such as bedding, Havan offers a wide selection of SKUs; in noncore categories such as appliances, it carries a narrower selection. With this strategy, Havan avoids intense head-to-head competition with the major home-appliance chains. The fairly high density of stores in Brazil’s Santa Catarina region facilitates distribution, and the company maintains a large distribution center to service the area.

In categories such as beauty and grocery products, for which consumers are less willing to travel, retailers need to develop smaller store formats and adapt their product range and service model to serve the interior in a cost-effective way. For instance, Chocolates Cacau Show expanded into the interior by using a smaller-format store—Loja Light—that is intended for cities with fewer than 70,000 inhabitants and requires an initial investment approximately 70 percent less than that for a conventional store. Today, Loja Light stores represent more than 20 percent of the company’s properties.

Retailers can also join forces with companies that already have a presence in the interior, embedding an outpost for their products or services in existing stores. For instance, mobile phone companies that want to expand their reach are teaming up with nontraditional points of sales such as local pharmacies and beauty salons to sell prepaid mobile plans. Similarly, Subway sandwich shops are partnering with gas stations and bus terminals to expand into smaller cities. These outposts fit in spaces as small as 430 square feet (40 square meters), and Subway plans to have 8,000 of them in Brazil in ten years. Alternatively, two or more retailers can join forces to extend their reach into interior cities. For instance, Love Brands joined up with three other known Brazilian brands—Imaginarium, Balonè, and Puket—to offer consumers in interior cities a diversified mix of products ranging from accessories and novelty gifts to underwear and sleepwear. With 39 locations across the country, the stores target interior cities with populations of 40,000 to 200,000.

Create a Multichannel Strategy

The explosion of mobile devices and social media is transforming how consumers connect with one another and make buying decisions. Studies consistently show that Internet penetration drives e-commerce—a dynamic that has played out in the U.S., other developed economies, and China. On a global basis, Brazil already ranks fifth in terms of the total number of Internet users. More than half of the country’s population is already online, and over 60 percent is expected to be connected by the end of the decade. And because a growing number of consumers use mobile phones to access the Internet, the emerging 3G and 4G networks will make e-commerce faster and easier. These faster networks already outnumber slower 2G connections in Brazil and are expected to account for more than 80 percent of mobile Internet access in 2018. As a result, the Internet may reach some nonurban areas and the lower rungs of the economic ladder in Brazil more quickly than traditional retail stores will.

Citing trust issues, the lack of reliable delivery, difficulty with returns and refunds, and the need to see and touch products, Brazil’s interior consumers tend to purchase less online than their big-city counterparts, but they do use the Internet for researching potential purchases, making brand decisions, connecting with friends, and staying on top of trends. This holds true for most categories, including electronics and groceries. For example, 25 percent of respondents in Brazil’s major metropolitan areas said they might use the Internet to purchase consumer electronics, compared with only 18 percent of respondents from interior cities.

Given these realities, forward-looking retailers must create a strategy for Brazil’s interior that integrates multiple channels—both on- and off-line. This will allow them to expand their reach in lower-density regions. As noted earlier, Eletrozema has small showrooms that shoppers can visit but offers more merchandise online and through catalogs, integrating three channels to meet the needs of local customers. Morena Rosa, a fashion company targeting interior cities, sells its apparel through a combination of company-owned stores, franchises, multibrand stores, and an e-commerce platform. The company invests significantly in marketing (recent campaigns have featured Sarah Jessica Parker and Naomi Campbell), hires bloggers, and uses social media such as Facebook and Instagram to spread the message to interior-city fashionistas. Natura Brasil, a leading cosmetics player, recently complemented its direct sales with an online channel—Rede Natura—that offers its beauty consultants another way to serve customers. Boticário’s franchise owners began spontaneously visiting nearby towns that were too small to support a retail presence. This direct-to-consumer sales operation is now an established channel for the company.

Until consumers in interior regions are more comfortable purchasing on the Internet, retailers can use websites or mobile apps to drive shoppers to offline stores. Online promotions, discounts, loyalty programs, and celebrity advocates are effective ways to engage consumers and turn them into customers. An added bonus: with more data on shoppers’ online and in-store activities, purchase patterns, and preferences, smart retailers will be able to create highly targeted, relevant marketing campaigns and in-store interactions.

Because the Internet breaks many of the compromises that consumers face in their traditional off-line shopping experiences by providing greater convenience, speed, price transparency, and product information, we expect that e-commerce activity in Brazil’s interior will grow significantly in the coming years, as it has in other developed countries—and retail companies must be ready.

Rethink Operations

To reduce the high cost of serving interior regions, retailers must rethink their approach to logistics and inventory management. Modern retail models tend to rely heavily on proprietary distribution methods. To keep costs low in the interior, however, outsourcing logistics to a third-party provider may be a better option—particularly if companies can find vendors that focus on distributing in specific regions and have a critical mass of customers.

Inventory management is another area of operations that retailers should revisit when serving inland markets, so as to further control costs. A common pattern we’ve observed is a trend toward stocking stores with broad but shallow assortments of merchandise, such as clothing in one instead of many colors so that shoppers can still get a sense of the item and how it fits. In fact, many retailers offer a wide range of product categories that is similar or superior to competitors’ offerings in larger cities. Although they stock fewer options within each category, retailers in the interior complement these shallow assortments with online offerings. Also, some companies increase their store footprint or storage areas so that they can stock more merchandise and reduce delivery frequency—viable options in the interior, where real estate costs are lower and distribution costs are higher.

Develop a Local Workforce

When it comes to the availability of qualified managers, engineers, and other employees, Brazil lags behind 13 countries, including Russia, India, and China (the other BRIC nations). (See Turning Brazil into a Business and Investment Hub , BCG report, April 2013.) Given the shortage of local talent, retailers that want to compete in the country’s interior must develop strategies to attract, develop, and retain human resources.

Franchise models can help overcome some of the people challenges by attracting motivated entrepreneurs with a clear stake in the business and a strong incentive to succeed. Boticário’s franchise model allowed the retailer to rapidly expand to more than 3,600 stores in more than 1,500 cities—80 percent in the interior. Other companies draw talent to less developed areas through internal mobility programs. For example, food producer BRF transfers people from the northeast to the midwest, where skilled employees are in short supply.

Companies must also make targeted investments in training. Eletrozema trains 70 managers per year in its corporate “university.” Leading snack company Mondelēz International has a “food university” to train employees in the northeast region of Brazil. McDonald’s and Ambev also have their own universities. Such efforts can go beyond company walls. Novartis, a leading pharmaceutical company, partners with the Federal University of Pernambuco to offer the local community a free postgraduate course in drug manufacturing. The Brazilian Franchising Association recently partnered with Sebrae to offer training in 120 interior cities to 25,000 people who own small businesses or plan to become entrepreneurs.

Today, a striking gap exists between where Brazil’s leading retailers currently operate and where future growth is projected to come from. To reposition themselves for success, the country’s retailers must follow consumer demand growth as it migrates from the major coastal cities to the interior. The five strategies outlined above will help companies make the leap—and do so profitably.