Consider the following scenario: your company’s new snack-food offering is a major hit. Manufacturing is humming, inventory is robust, you’ve locked in distribution, and forecasts appear spot-on. In every respect, this would be a supply chain success story, except for one: consumers can’t get enough of the product. Literally. Trucks are chronically late, capacity is insufficient, and missed delivery windows are exasperating retailers.

It may be little consolation, but you would hardly be alone. Consumer packaged goods (CPG) companies are having a progressively tougher time getting their products to customers. Transporting goods to retailers is now the greatest worry of supply chain leaders, according to the

The Capacity Crisis

Shortages of truckload capacity pose significant challenges to transportation buyers. Meanwhile, according to the US Bureau of Labor Statistics, driver turnover is more than 100 percent, and recruitment is difficult for carriers. Delays and congestion worsen each year, threatening delivery times and further straining capacity. Intermodal transit, a crucial relief valve, continues to fall short of its promise, frustrating shippers by its lack of speed and reliability. SKU proliferation, channel fragmentation, and the unrelenting demands of retailers are only adding to the pressures. Not only are these challenges likely to persist, but their convergence creates a more fundamental, structural change in the overall transportation system.

On the whole, the CPG industry spends about $15.5 billion each year on transportation, which has up to a 5 percentage point impact on the bottom line. In the past, CPG executives didn’t have to give transportation much thought. Cyclical bumps such as fuel price ups and downs created cost headaches, but on the whole, logistical snags amounted to minor management issues. Today, the problems are systemic and structural. Increasingly, leaders must make uncomfortable trade-offs: pay more to fulfill service level expectations or seek cost efficiencies, often at the expense of speed and reliability.

Transportation costs are eroding supply chain cost savings. Since the last BCG/GMA study in 2012, freight costs have risen by as much as 14 percent, reversing the effects of all supply chain cost-saving efforts. Indeed, only a third of CPG companies have been able to trim transportation costs in the past two years.

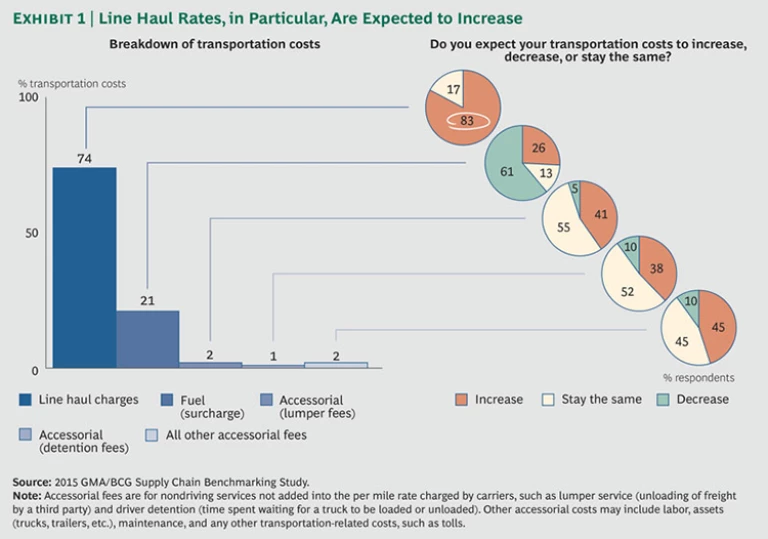

The recent drop in fuel prices provides little comfort, as savings will be offset by further rises in other transportation costs. For example, an overwhelming 83 percent of respondents to our survey expect line haul rates, which make up more than 70 percent of transportation costs, to rise. (See Exhibit 1.)

Across the board, service levels are declining. Perhaps most telling is the metric that has fallen the most: on-time requested arrival date, which fell industry-wide by 4.8 percent between 2012 and 2014.

Despite gains in forecasting accuracy, more than 60 percent of companies saw inventories grow in the past two years: inventory on hand rose on average by nearly four days. Last-mile transportation challenges were the biggest reason cited by supply chain executives for why greater forecasting accuracy hasn’t shaved inventory levels or improved service. CPG companies are now forced to take a defensive posture, building inventory to hedge against transportation shocks and longer transit times.

Driver shortages and aging infrastructure are the root causes of the transportation problem. In what was once a cyclical environment, fuel price volatility was the scourge of supply chain leaders. Now leaders battle capacity constraints and cost escalation, structural challenges that appear to be lasting trends. Underlying these challenges are two external factors: driver shortages and aging infrastructure.

The American Trucking Association estimates that by 2022, the industry will be short 240,000 drivers. Given that most freight is transported over the road (OTR) and that self-driving technology is still a long way off, this is a serious concern. Carriers struggle to recruit and retain drivers; the decline in real wages (6 percent in the decade ending in 2013), the difficult lifestyle, and the lure of more lucrative, stable occupations (such as construction) have made drivers scarce. New regulations (limited hours; the compliance, safety, and accountability program; and electronic data logging) cap driver miles, further dampening capacity.

With demand for drivers exceeding supply, carriers are being forced to spend more. Driver scarcity allows carriers to be more selective. Increasingly, carriers are refusing unattractive jobs (congested lanes, less than truckload [LTL] shipments, and runs that require drivers to wait with loads). Bids have been steadily rising; CPG companies are being hit with price increases as large as 15 percent.

Aging infrastructure and its corollary, growing congestion, are also to blame. America’s deteriorating roads, bridges, and railways receive C or D ratings from the American Society of Engineers. And according to the ASE, roughly half (or less) of what is needed to fix roads and bridges is spent each year, indicating little chance of improvement.

CPG companies, retailers, and carriers alike anticipate that OTR congestion will worsen over the next few decades, as long-haul truck traffic grows to a projected 662 million miles per day. Recurring peak-period congestion will affect more national highways, creating slowdowns or stop-and-go conditions on more than 60,000 miles. Although intermodal use is growing (demand rose nearly 11 percent in 2013), the rail industry can’t keep up with demand. Intermodal itself may become overstressed and more unreliable than it is at present if the 63 percent of respondents who said they expect to use more intermodal actually follow through on their plans.

With trucking becoming an increasingly undesirable career and infrastructure continuing to erode (and with no comprehensive remediation in sight), it’s clear that CPG companies’ supply-chain leaders can expect little relief from their transportation headaches. Fragmented channels, SKU proliferation, and retailers’ growing demands only compound the problem.

Optimizing Transportation: The Need for SPEED

As a supply chain issue, transportation used to be neatly siloed, a straightforward and predictable function. But the complexities and magnitude of today’s external challenges are far beyond supply chain leaders’ traditional purview. Leading CPG companies recognize that such challenges call for a more proactive approach, as well as more integrated thinking and solutions. These companies are assessing their transportation strategy regularly, integrating it into their supply-chain business planning processes. More than ever, they know that they need to be able to adapt to shifting constraints and a dynamic environment in a more systematic manner.

Clearly, there is no single solution. But a number of tactics, some already familiar, can go a long way toward mitigating the pressures and significantly improving transportation performance—especially when deployed as part of an overall strategic plan. To the industry, these tactics represent a potential cost savings of 7 percent of spending on transportation, or roughly $1 billion. Individual companies are already realizing cost savings and other tangible benefits.

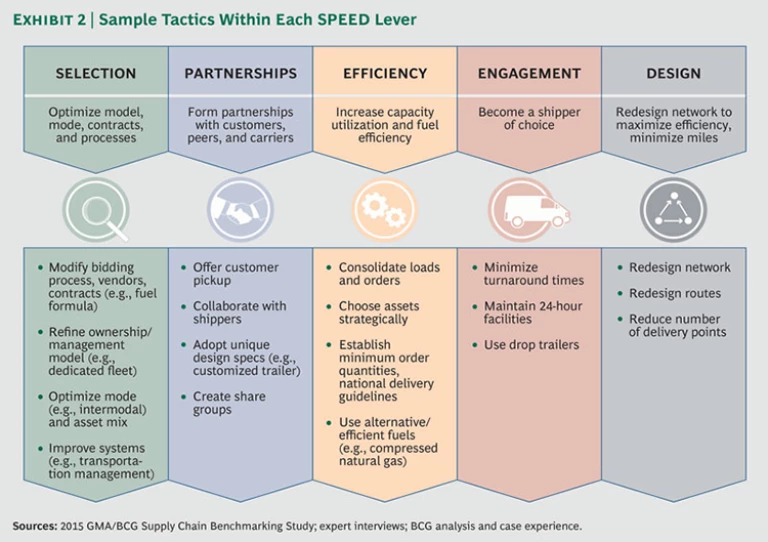

To zero in on the critical factors and most helpful tactics, it’s helpful to consider the repercussions of a transportation interruption. For example: How much would sales decline, if at all? And to what extent would customer relationships be hurt? Would shelf placement be affected? Is there a limited selling season or other constraints? Collectively, the tactics are part of a framework of five levers that BCG calls SPEED: selection, partnerships, efficiency, engagement, and design. (See Exhibit 2.)

Lever 1: Selection. Selection involves choosing the right ownership model, shipping mode, contracting approach, and processes. Most CPG companies (59 percent of respondents to our survey) manage and execute transportation in-house, believing that they need a firsthand view of their customer service, while 41 percent rely on a third- or fourth-party logistics provider, despite its higher cost. Private fleets, which many CPG companies recently abandoned in favor of third-party fleets, are not off the table. The survey found that 63 percent of companies expect to increase their use of intermodal to alleviate the high costs and capacity squeeze of OTR transport. Others optimize the transportation function through sophisticated transportation management systems and bidding processes.

Lever 2: Partnerships. Partnering with customers, carriers, and other manufacturers represents another viable route for CPG companies. (See “P&G Teams Up for Success.”)

P&G TEAMS UP FOR SUCCESS

Carrier consolidation at P&G has actually facilitated collaboration with customers. Fewer in number than in the past, these carrier relationships have become stronger and more strategically oriented. Through its use of strategic broker partners, the company has more drivers available to fulfill surge capacity and boost the overall flexibility of its supply chain.

Consolidation has also helped P&G resolve service problems with retailers more quickly. Service at one distribution center has improved by 25 percent. Joint planning has brought to light data transmission errors and provided customers with better inbound service, thereby increasing distribution center efficiency.

Options include customer pickup, collaboration with other companies to share warehousing or truck space, and combining loads for a full truckload. Bumble Bee Foods, for example, is combining its products with those of three other companies that ship to the same retailer. Share groups are another option, in which the CPG company, retailer, and shipper convene to consider best practices.

Most of the CPG companies in our survey are collaborating with retailers. Some have boosted order volumes and accuracy by conferring with retailers in the order process. A few even share order forecasts with their carriers to help them better anticipate volumes.

Lever 3: Efficiency. Increasing load size is one of the simplest paths toward better capacity utilization. Companies can consolidate orders using any number of tools, from algorithms to order grouping across departments. Cutting packaging weight, improving truck turnaround times, and reducing “empty miles” can also boost efficiency. Other techniques include limiting LTL shipments to a few days a week and choosing assets strategically: using lighter day-cab trucks for shorter-haul shipments, private fleets for the most time-sensitive goods, or intermodal for shipments with longer lead times, such as replenishment freight.

Setting national delivery guidelines and minimum order quantities at the right levels is another way to reduce the number of trucks needed. Rerouting can also save thousands of miles a week; GPS data is useful for optimizing routes to avoid congestion and reduce mileage.

Lever 4: Engagement. Becoming a shipper of choice is a strategic decision. CPG companies can work with their carriers to overcome OTR capacity constraints in a variety of ways: by giving carriers predictable volume estimates; minimizing turnaround times; providing 24-hour access to distribution centers; ensuring neatly stacked, full pallets (for faster loading and unloading); and using drop trailers. Predictable lanes, early warnings, and data sharing are also attractive to carriers. These options can be applied selectively (by product line, carrier, or time requirement) or across the entire portfolio. Consider the efforts taken by a major food company: it expanded branch access to 24 hours; upped its percentage of drop trailers to between 70 and 80 percent (with plans to increase that rate); and is speeding turnarounds by streamlining check-in and minimizing wait times at facilities.

Lever 5: Design. Given the current transportation environment, network design is a priority. Our benchmarking showed that 72 percent of CPG companies are now engaged in network redesign, compared with 6 percent in 2012. Companies can reconfigure their logistics network to achieve efficiencies while also improving service. This includes traditional strategies such as optimizing routes and the number of delivery points.

In a pilot program, Bumble Bee Foods is restricting LTL shipments and has created specialized multistop routes to consolidate them. Its savings thus far are 2 percent of total freight costs. Land O’Lakes is aggregating orders to reduce the number of stops per truck on multistop customer shipments. In this way, the company aims to make freight more carrier friendly and boost on-time delivery.

Network design can serve several goals. Positioning facilities on high-volume lanes eases capacity constraints and removes bottlenecks, which, in turn, raises service levels. Consolidating facilities to remove redundancies and leverage scale can reduce distribution costs. By moving facilities closer to customers, CPG companies can also improve product freshness, and relocating closer to peers facilitates collaboration.

The most sophisticated companies are thinking about network design as a dynamic issue, rather than as a one-and-done decision. Supply chain design tools and systems enable transportation leaders to visualize product flows and evaluate network performance on a more regular basis. Land O’Lakes used a supply-chain-design analytics tool to help decide whether to continue using a private fleet for the supply chain of a recent acquisition or to integrate the acquisition’s supply chain into an existing distribution network. The tool helped the company visualize the degree of customer overlap in the two supply chains; with 90 percent overlap, it decided to integrate the two systems. A simulation of the combined supply chain uncovered the potential to improve shipment load factor by 12 percent, which Land O’Lakes subsequently did to realize the savings.

P&G recently created distribution mixing centers closer to population centers. In addition to helping sync product flow with demand, the new routes have helped P&G ease its environmental impact by maximizing vehicle fill and facilitating the use of alternative fuels. With 75 percent shorter delivery distances, the company now has the ability to deliver 80 percent of customer volume in a single day of transit.

Weighing All the Options

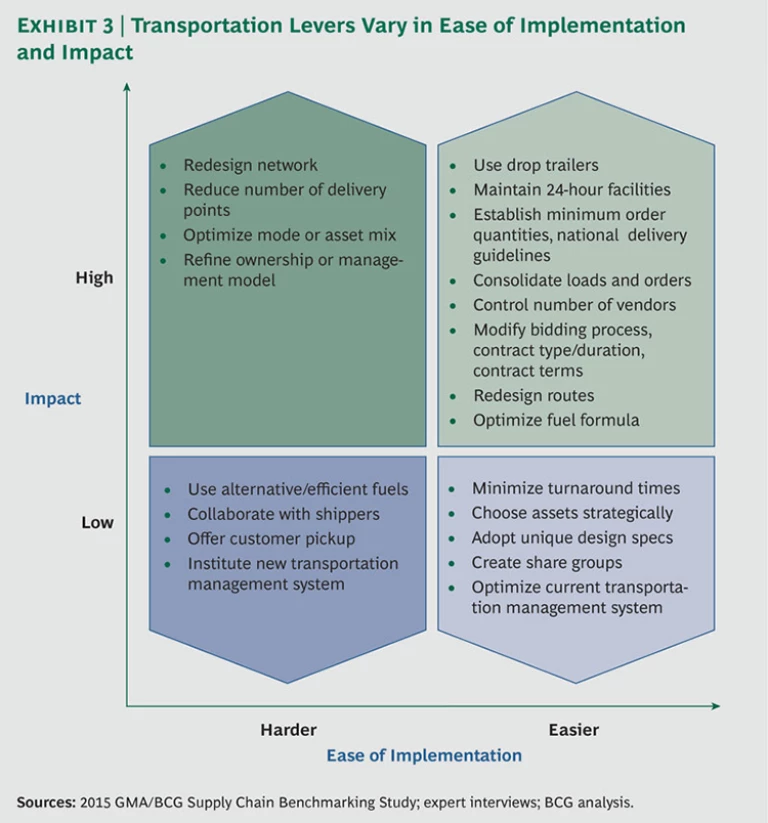

The five levers that constitute the SPEED framework vary in ease of implementation and impact. (See Exhibit 3.) Among the highest-value components are network design, drop trailers, and order consolidation. Moreover, some levers are better suited to replenishment freight and others to customer freight.

Some CPG companies are also adopting such innovative approaches as shared distribution centers. Here, a third-party broker seeks other suppliers to use extra space in a company’s distribution center, facilitating combined, full-truckload shipments to retailers. Others are employing an open-book policy with carriers, which provides visibility into carrier margins.

Although ease of implementation and impact are crucial considerations, the choice of tactics cannot be made in a vacuum. Step one for any company is to assess its particular needs by evaluating the role of transportation in the enterprise and in each business unit. Where should transportation fit within overall supply-chain priorities? What percentage of sales (and of the supply chain budget) do these costs account for? How flexible is the supply chain, and can transportation strategy help mitigate shocks?

Thinking strategically about transportation means distinguishing between those products for which transportation is—or isn’t—a key differentiator. “Time agnostic” products (such as paper towels or canned corn) may be more suitable for low-cost transportation. With “mission critical” products, in contrast, time sensitivity trumps cost, and transportation interruptions have serious repercussions (think of Halloween candy in October or rock salt in a region hit by snow and ice). A third category, “unique” products—fragile items (eggs), perishables (milk), and hazardous goods (aerosol cleaners, household solvents)—often require specialized transportation. These segmentation decisions should be driven by business priorities, which is yet another reason why transportation-focused senior leaders need to be involved in the strategic planning process.

From Adversity to Advantage

Mounting external challenges are squeezing CPG companies’ resources and business processes. But for any company, a solid, well-executed transportation strategy can become a key differentiator. When transportation is integrated into strategic business planning, it has the potential to enable overall business success. Outside of the steps any one CPG company might take independently, the industry could begin a dialogue through broader share groups or consortiums to brainstorm and implement solutions. For example, retailers could increase the use of dedicated windows and allow more drop trailers to decrease wait and unload times for drivers. CPG companies could engage in more collaborative shipping programs or backhaul to better utilize the limited OTR capacity across the industry.

New priorities and technologies are emerging that offer promise as well as potential disruption. Alternative fuels and new electronic tools (GPS-based technologies, mobile apps) represent potential double-duty solutions: they can support sustainability goals (which are becoming increasingly important), while providing relief from key structural problems, such as capacity and congestion. Further down the road, self-driving vehicles and on-demand ride-sharing programs along the lines of Uber may render driver shortages a thing of the past.

Above all, success with transportation in the new environment requires that transportation be elevated to the supply chain strategic agenda. Supply chain leaders must communicate the issues these challenges pose—and their strategic implications—to their peers so that the organization can take concerted action. Companies can then integrate transportation into the sales and operating planning process. With a robust toolkit of tactical levers, agile supply chains, and a comprehensive strategic approach to transportation, CPG companies have the opportunity to realize much more than cost savings. They can transform transportation from a source of adversity into a source of competitive advantage.

Acknowledgments

The research described in this report was sponsored by the Grocery Manufacturers Association’s Supply Chain Committee and was performed by BCG in partnership with GMA. The authors would like to thank the members of that committee as well as Daniel Triot at GMA. In addition, the authors offer their sincere thanks to their BCG colleagues Demi Horvat, Katherine Jones, and Laura Sluyter.