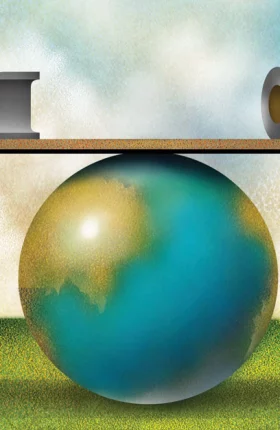

Calls for conservation and sustainability are increasingly vehement and urgent. Vital natural resources are being depleted, even as consumption levels climb. Population increases are one measure: in 2050, the world’s population will total 9.6 billion people, an increase of 2.6 billion over the current total that will occur mostly in African and Asian countries.

Related Article: Steel as a Model for a Sustainable Metal Industry in 2050

Expect a transformation. By 2050, the world and the way it uses its resources will be different. Rules are changing, societal pressure to act more sustainably is growing, and technological advances are creating new possibilities. The push for sustainability is challenging ways of doing business across industries. But for the mining and metal sector, the challenges are fundamental: these companies are extractors and users of finite mineral resources, and they face significant demands and expectations regarding sustainability from across the value chain and from various stakeholder groups.

Mining and metal companies can meet these challenges. Doing so requires changes in mind-sets and business models and a long-term view; sustainability will be an imperative in the years leading up to 2050, and beyond.

The Boston Consulting Group, in conjunction with the Mining & Metals in a Sustainable World 2050 initiative of the World Economic Forum, has analyzed the outlook for mining and metal companies and established a framework to navigate these changes.

No End in Sight

Mining and metals are essential to the global economy and societal development. These companies stand at the beginning of most value chains, supply crucial materials and products, and generate trade, employment, and economic development globally. This sector will also be central to meeting the demand for global growth in a more sustainable world.

With that foundation, BCG and the World Economic Forum's initiative find no reason to anticipate an end to mining. Primary extraction will continue, although volumes are unlikely to grow in line with GDP growth. Therefore, to prosper as businesses that retain a license to operate, mining companies will have to combine cost-effectiveness with environmentally and socially responsible behavior, leading to new partnership and operating models.

Nor will metal companies disappear. Metal companies can survive by acting as liaisons between commodity producers and end industries. Opportunities will exist for these companies to adapt business models and reposition themselves as materials providers.

Already, the mining and metal industry is reacting to the new agenda. A Joining Forces: Collaboration and Leadership for Sustainability found that 80 percent of senior executives believe that sustainability-oriented strategies are essential for current and future competitive advantage.

A Framework and Principles for Sustainability

To make the necessary adjustments and to put sustainability at the heart of corporate culture, the initiative compiled a framework of key questions that mining and metal companies must answer:

- How will the balance of primary and secondary commodity supplies look at various points in the future?

- Which supporting resources (such as water and energy) face the largest risks of scarcity and cost increase?

- What long-term downstream and end-use trends could most affect the sector?

- Which technological developments will affect mining and metals, and how?

- How can the sector attract people with the right skills?

- How is regulation being shaped, and how are different nations’ varying regulatory speeds being addressed?

- Which parts of the business model and overall strategy need to be adjusted for a more sustainable world?

Mining and metal companies can turn to this framework to check the progress of their strategies toward sustainability as the environment evolves. They can evaluate and adjust their approaches or trigger new action plans.

What are they planning for? A set of overarching principles sets the direction that mining and metal companies must target. The end state could encompass the following: environment and climate conservation, fair value and development, transparency and human rights, and health and well-being.

Changing Resource Use

A key element in the new sustainable world is circularity. Products will have greater longevity as they are increasingly reused and recycled. Instead of being thrown away at the end of their life, products (or, at least, many of their components) will be dismantled for recycling and reuse. This will demand changes at several points in the value chain.

In particular, product designs need to be altered so that products, and their components, can more easily be repurposed when they are no longer useful in their original states, at the end of their life. It should be possible for components to be easily and inexpensively extracted. Steel rods and beams from buildings could be reused after demolition. Components from electrical products such as smartphone displays should be easy to extract. Achieving more reusability will demand standardized component designs and specifications along with close collaboration and cooperation along the value chain.

Reuse can also be ensured through remanufacturing, in which a product is not scrapped but disassembled, cleaned, repaired, and reassembled. This is an extremely environmentally friendly and energy-efficient way to make domestic appliances, machine tools, and (in particular) engines and turbines reusable. Reusing a remanufactured engine rather than producing a new one consumes up to 83 percent less energy and can save up to 87 percent of emissions.

Governments are likely to push circularity by using life cycle assessments, which measure the true environmental impact of a product. Governments can also be expected to demand a reduction in the waste associated with mining and metals—currently estimated at 10 billion tons per year, or 40 to 55 percent of the global total—and an increase in recycling.

More efficient treatment of waste would also benefit mining companies. It has been estimated that with the right technology for treating bauxite waste, aluminum production per ton extracted could be increased by 20 percent, a significant value gain.

Recycling rates will need to rise. Wasteful bottlenecks, such as the 30 percent of aluminum scrap that is not collected in the U.S., must be eliminated. End-of-life recycling rates vary from 40 percent for zinc to 85 percent for steel. Even in high-recycling steel, an increase of recycling rates (and scrap used in new steel) is possible. More recycling also means more-efficient energy use. Recycling aluminum takes only 5 to 10 percent of the energy needed to produce primary aluminum. When steel is produced using 100 percent scrap inputs, the process uses up to 60 percent less energy than the same process via the integrated route, which cannot run only on scrap.

In the face of the sustainability imperative, mining and metal companies must address not only the overarching trend toward sustainability but also other relevant supporting factors, including the impact of technology, staffing needs, and relationships with host communities, especially in mining. A clear understanding of the potential challenges and opportunities is key to prospering in the new sustainable world. By acting now, mining and metal companies have the opportunity to define the role they can play and embrace the changes to come.