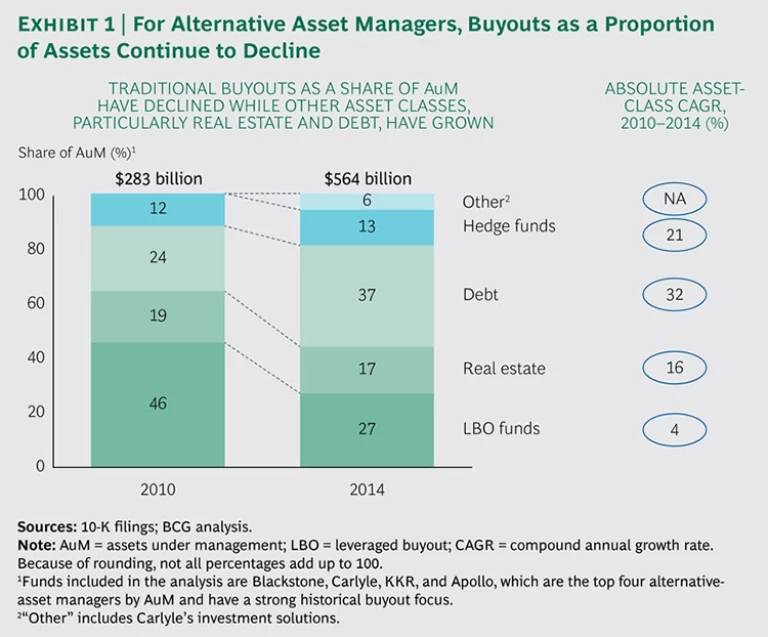

More than a decade ago, large private-equity (PE) firms such as The Blackstone Group, Kohlberg Kravis Roberts (KKR), and The Carlyle Group started to pursue diversification strategies that have allowed them to significantly increase assets under management (AuM) and develop into broader alternative-asset-management firms. Firms took different diversification paths, including entering new regions and sectors, making different types of PE investments, such as venture capital and minority stakes, and investing in other alternative-asset classes. For example, an analysis of the AuM of four large alternative-asset-management firms shows that they have continually added to their investments in debt and specific real assets, including infrastructure, natural resources, and real estate, while shifting focus away from traditional leveraged buyout (LBO) funds. Among these firms, LBO funds as a percentage of AuM have declined from 46 percent in 2010 to 27 percent in 2014. (See Exhibit 1.) Within this, the surge in debt fund-raising, for direct lending in particular, has been notable. In 2014, financial investors raised $29.1 billion for direct-lending funds, compared with only $7.1 billion in 2012.

Why Did These Firms Choose to Diversify?

Our analysis reveals several broad motivations for diversifying: firms’ search for growth (and sometimes also their desire to go public), the synergies achievable from being present across different alternative-asset classes, and demand from fund investors. (See “Blackstone: Building Scale.”)

BUILDING SCALE

As one of the first traditional buyout funds to diversify, Blackstone exemplifies the way firms have expanded into other asset classes. (See the exhibit below.) Blackstone’s diversification started with the launch of its hedge-fund business, Blackstone Alternative Asset Management (BAAM) in 1990. BAAM arose from the opportunity and the investor need created when Blackstone’s management team divested some Blackrock shares and needed to manage the proceeds. Similarly, Blackstone established its real-estate business in 1992 to capitalize on real-estate investment opportunities that arose after the buyout fund acquired several hotel businesses. The real estate group formally launched its first real-estate fund in 1994 with a modest $485 million in AuM.

After pausing its diversification drive for several years, Blackstone set up a corporate-debt group in 1999. In 2008, the firm established a full-range debt-investment business—including, for example, mezzanine debt, special situations, collateralized loan obligations, and senior secured loans—by way of a reverse merger with GSO Capital Partners. Additionally, in 2005 Blackstone acquired the Park Hill Group, a third-party advisory business that conducts placement services for funds.

Further pushing the limits of diversification, Blackstone has also subdiversified within each of its businesses across regions, industries, and investment structures. For example, Blackstone has established regionally dedicated real-estate funds such as the Asia Real Estate Fund and the Blackstone Real Estate Special Situations Advisors. Blackstone’s PE business, to cite another example, features four categories of funds: traditional buyout, tactical opportunities (including minority investments), energy, and secondary products.

Although Blackstone was opportunistic in its initial entry into other asset classes, it made a strategic decision to pursue diversification only in asset classes in which it could build a world-class business at scale. In some cases, such as with venture capital, the challenge of building a truly scaled global business was a deterrent to entry.

Another example is Blackstone’s divestment of its advisory business—including restructuring advisory as well as placement advisory—whose growth was constrained by potential conflicts with Blackstone’s investment business. Because Blackstone couldn’t grow the advisory business to scale, it decided to divest it, in keeping with the group’s broader diversification strategy.

Firms Aspire to Increase AUM

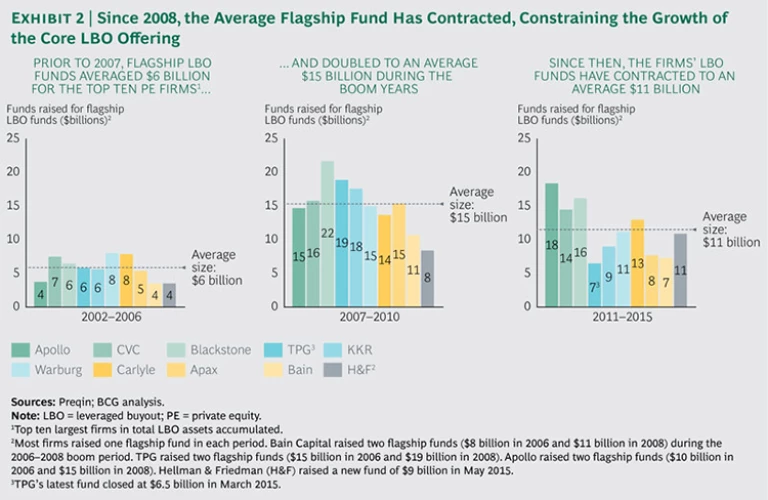

During the boom years from 2006 to 2008, some of the largest buyout funds ever were raised. The influx allowed firms to significantly increase AuM. Since 2008, however, many general partners (GPs) have faced a more challenging fund-raising environment. BCG analyzed funds raised from 2002 through 2015 by the ten largest PE firms and found that the average capitalization of new flagship funds more than doubled from around $6 billion from 2002 through 2006 to roughly $15 billion from 2007 through 2010. Since 2008, however, the average size of new LBO funds contracted by 25 percent and fell to around $11 billion from 2011 through June 2015. (See Exhibit 2.) Although there are exceptions—the latest Apollo fund raised around $18 billion in 2014—most of the top firms have seen a significant decline in the size of new LBO funds.

Firms therefore went looking beyond traditional buyout funds to grow their AuM. For many large fund investors, also known as limited partners (LPs), PE makes up a relatively small proportion of their overall investment allocations. For example, CalPERS, the influential California state pension fund, has a total of $296 billion in assets, but invests only $31 billion (or slightly more than 10 percent of assets) in PE. In comparison, CalPERS invests 53 percent of assets in public equities and 9 percent in real estate. In fact, according to a London Business School study of 1,200 U.S. and UK pension funds, public pension funds directly allocate on average only about 5.6 percent of their assets to PE funds. While firms have made an effort to increase allocations to their buyout funds, they are also increasing the availability of investment opportunities in other asset classes to increase their allocation share with LPs.

GPs Aspire to Go Public

Several PE firms have aspired to go public as well. But because of the cyclical nature of the buyout industry, PE firms need to diversify to make their shares more attractive to initial public offering (IPO) investors. The five firms that have gone public (Blackstone, KKR, Apollo, Carlyle, and Oaktree) had all diversified into two or three other asset classes (such as real estate, debt, or funds of funds) by the time of their IPO. Any PE firm looking to go public needs to address the market’s concerns about the volatility of PE performance fees. For example, Carlyle’s IPO in 2012 was priced lower than expected because of the market’s concerns that Carlyle, with 63 percent of AuM in buyout investments, was insufficiently diversified. At the time of Carlyle’s IPO, Fortune magazine reported that “it’s also possible that Carlyle received an extra demerit for being the private equity-est of all the publicly traded private-equity firms (i.e., the least diverse).” At the time, 63 percent of Carlyle’s AuM was in buyout investments, a number that has since declined to about 33 percent, bringing Carlyle more closely into line with its peers.

Firms Realize Substantial Operational Synergies from Diversification

Given their growth ambitions, some firms sought to leverage their intellectual capital by realizing operating synergies from their diversification activities as a source of competitive advantage. They have invested significantly in risk and compliance systems to ensure that they can realize operational synergies such as the following:

- Deal-Sourcing Synergies. Flagship buyout funds can provide visibility across a broad array of investment opportunities, in many cases, across locations and industries. Therefore, buyout funds receive leads to potential deals that, while they are not ideal buyout transactions, might be more suitable for funds focused on other asset classes. Similarly, a buyout fund might acquire a company that includes a simultaneous opportunity to invest in another asset class, such as debt. For example, many of Triton’s buyouts have involved a debt component that would be resold to the market after the acquisition. But Triton found that in several cases the debt offered an attractive return and was potentially a good investment for its debt fund.

- Deal Evaluation Synergies. The ability to accurately value companies is a core expertise of many PE firms. The same valuation expertise can be applicable across asset classes if target investments are similar. For example, Triton’s core expertise is in investing in midsize Western European companies in the consumer, business services, and industrial sectors. Triton has considerable skill in evaluating such companies and, therefore, seeks different investment opportunities across asset classes that suit its valuation expertise. Its entry into the debt market allows it to focus its valuation expertise on the same set of target companies but directs it toward a different asset class.

- Deal Execution Synergies. Because diversified PE firms can offer a larger range of investment solutions, including mixed-asset-class integrated solutions, such firms can also be compelling partners for corporations. This capability can be a significant competitive advantage for both closing deals and exposing LPs to differentiated investment opportunities. In many cases, having a multiasset platform can also help close a deal. Blackstone’s buyout fund, for example, frequently partners with its real-estate division to structure and invest in acquisitions. Blackstone’s acquisition of Centre Parcs and Cineworld are prime examples of deals that leveraged expertise from both the buyout and the real estate groups.

- Portfolio Management Synergies. A diversified firm can also leverage its expertise from different funds to help its portfolio companies grow. For example, Blackstone’s real-estate-operations team contributes significant development expertise to help grow the companies acquired by the buyout business. Deals such as the Center Parcs and Cineworld acquisitions, which included sizable real-property holdings, created opportunities for Blackstone to leverage the scale of its real-estate operations to develop new properties and grow the assets.

Likewise, Blackstone’s global group purchasing program harnesses the combined purchasing power of Blackstone’s PE and real-estate portfolio companies. More than $4 billion of annual spending is managed through group purchasing programs in more than 70 categories, including such essential products and services as IT hardware and software, office supplies, overnight small-parcel shipments, hotels, insurance, energy, and telecommunications. On a global basis, approximately 95 percent of Blackstone’s portfolio companies have taken advantage of the group purchasing initiatives. Taken together, Blackstone’s portfolio companies represent a significant market, enabling its vendors to deliver outsize cost savings. As a result of its critical mass and buying power, the Blackstone Group purchasing program has achieved more than $700 million in annualized savings for portfolio companies since 2005.

There Is Investor Appetite for Diversified Solutions

In addition to the operational synergies, there are also substantial marketing synergies from diversification. KKR, for one, has relentlessly built on the benefits that its diversification affords to offer its LPs a compelling value proposition. (See “KKR’s Diversification in the Round.”).

KKR’S DIVERSIFICATION IN THE ROUND

Johannes Huth, head of KKR Europe, the Middle East, and Africa, told us, “We have been thoughtful about our organic growth, entering new markets and businesses where we believe they build on our areas of strength, intellectual capital, and industry relationships and where attractive opportunities exist to further broaden our asset and investor base.”

As a matter of fact, few firms have gone further in building on the synergies unleashed by diversification than KKR—both between different products and in marketing.

For example, KKR’s real-estate team leverages resources from other KKR platforms, including the buyout group and the debt team. Access to KKR’s diverse platforms is a source of competitive advantage, because, Huth said, it “provides far greater resources to source, analyze, and execute real estate transactions and address the needs of our clients.” To cite another example, KKR’s credit platform has built on KKR’s buyout history and experience, and this has “resulted in a deep and established network of relationships with banks, advisors, companies, sponsors, and trading counterparties. It is this network that we believe gives us a competitive advantage of finding and identifying investments for our clients.” KKR recognizes that the sourcing synergies among its different investment platforms provide a competitive advantage that helps KKR generate better deals and, therefore, higher returns for its investors.

KKR also realizes marketing synergies through diversification. It has a dedicated 70-person sales team whose mandate includes offering tailored alternative-asset investment solutions beyond specific investment funds.

In short, KKR rarely passes up an opportunity to use its diverse investment platforms to improve deal sourcing and execution and to offer compelling value propositions to a broad range of investors.

Especially for large LPs such as pension funds, diversified funds can offer several compelling benefits, including the following:

- A Credible and Trusted One-Stop Shop. LPs can invest in multiple funds that match their asset-allocation needs. Pension and sovereign-wealth funds are typically invested across many different asset classes in order to diversify risk. For LPs that might have limited in-house capacity to pick the best of breed in each asset class, a trusted and credible diversified fund offers a compelling alternative.

- Lower Management Fees. Many large LPs are attracted to multiasset funds because they allow investors to deploy more capital through fewer GPs, thereby reducing overall management fees. Recently, U.S. public pension funds have come under political scrutiny for the amount they spend on management fees, and, as a result, they are reducing the number of GPs in an effort to cut costs. For example, CalPERS announced recently that it was looking to shrink its roster of PE managers by two-thirds to 120 in order to cut costs. Since that CalPERS announcement, other funds such as the Future Fund (Australia’s sovereign-wealth fund) have made similar statements.

- Better-Aligned Performance Fees. Some multiasset managers offer a combined-performance fee structure, which charges carried interest, or carry, only if the overall performance of all investments across all asset classes clears a specified combined hurdle rate. For example, an LP may invest with one firm across several different funds. Under a typical performance-fee structure, the LP would pay carry on every fund that outperformed its benchmark. Under a combined hurdle-rate structure, the LP would pay carry only if the net performance across all funds should exceed the required rate. This structure accounts for the underperformance of investments in some asset classes and better aligns the GP’s performance incentives with the overall performance of an LP’s portfolio.

- Curated Investment Solutions. LPs are starting to look for additional full-service asset-management solutions, in which PE firms have more latitude to allocate and invest capital on behalf of the LP across a range of funds. In many ways, large diversified funds are assuming the role of traditional asset managers rather than acting as typical PE GPs. In 2011, for example, the Teacher Retirement System of Texas (TRS) committed $3 billion to both KKR and Apollo Global Management to manage as a separate account. TRS committed an additional $2 billion to each manager in 2015. KKR and Apollo had mandates to invest the capital using several different strategies across their asset funds and even had the latitude to place capital in new investment opportunities as they arose. The partnership deal was attractive to TRS’s managers because they believed that the investment expertise of KKR and Apollo was superior to their own and would enable the fund to achieve better returns.

Blackstone’s new Total Alternative Solution Advisors is similar to the asset management services for large LPs but is targeted at high-net-worth individuals (HNWIs), enabling them to invest in one of Blackstone’s existing funds. Carlyle, for its part, builds on the fund-of-funds offering it obtained through its acquisition of AlpInvest, as well as hedge funds obtained when it acquired Diversified Global Asset Management. The result is a curated fund for HNWIs with a pooled vehicle that allocates capital across Carlyle’s buyout funds. Given that on average, HNWIs allocate only 2 to 3 percent of their invested capital to alternative assets (including both PE and hedge funds), there is clear potential to increase this allocation.

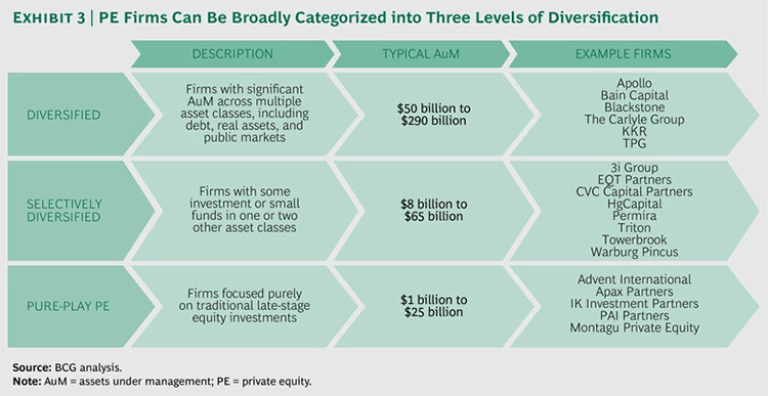

Why Do Some PE Firms Choose to Remain Pure Plays?

On the other end of the spectrum, many firms have remained focused, succeeding by specializing and demonstrating expertise and depth in specific industries or regions. The Boston Consulting Group recently analyzed the investment strategies of 19 of the largest PE firms. The analysis reveals that about a quarter of the firms—5—are still pure buyout funds. Of the 14 firms that have diversified, the majority—8 of 14—have selectively diversified along only one dimension, and only 6 have diversified across multiple asset classes. (See Exhibit 3.) At the 2015 SuperReturn International conference, Guy Hands, of Terra Firma, predicted that smaller firms would return to their PE roots and concentrate on smaller, focused fund-raising rather than seeking to become large generalist asset managers.

Pure-play PE firms offer critical advantages, including the following:

- They alleviate investor concerns that PE firms lose focus on core LBO activities as management attention disperses across multiple asset classes. By remaining pure plays, they can keep their top talent focused on their core activities.

- They eliminate the risk of incentive misalignment between GP and LPs. Some LPs are concerned that management fees are so high for large multiasset-class firms that performance fees become a secondary objective.

- They avoid concerns about deal allocation between funds. In many cases, diversified GPs have discretion to allocate investments to specific funds, as some deals might be suitable for more than one.

- They address LP needs for specific exposures. LPs looking to fill specific exposures in their portfolio will look for best-of-breed pure-play funds—for example, those that focus on a specific country. This can also apply to larger funds. Cinven, for example, has prospered by focusing on buyouts of large Eurozone players.

PE firms choosing between diversification and specialization will reach differing conclusions, depending on their current strategy and position in the market. Large diversified firms will continue to push to diversify and further establish themselves as alternative asset managers with multiple product lines. For example, while Blackstone is spinning off its advisory business, KKR Capital Markets continues to advise on executing financing transactions. Similarly, to strengthen its presence in hedge funds, in August 2015, KKR acquired a 24.9 percent minority stake in Marshall Wace, a London-based hedge fund with £22 billion in AuM. Meanwhile, Blackstone is contemplating launching a fund that, like Berkshire Hathaway, takes a long-term-value-investor approach to a relatively small portfolio of high-quality businesses.

Some midsize firms might engage in opportunistic diversification, either by acquiring or building a team in a sector adjacent to its core. Triton, for example, carefully and selectively diversifies as opportunities present themselves. It has started taking minority stakes in public companies and expanded into a £500 million debt fund while maintaining its focus on the types of companies that are in its buyout-fund portfolio, meticulously allocating control positions gained through debt purchases to its main PE fund and minority debt positions to its debt fund. Small, pure-play PE firms, meanwhile, will likely specialize further to clearly define their focus areas, be it by region, industry, or a matrix of the two. This strategy seeks to attract LPs that seek best-of-breed specialty buyout funds.

As should be clear, there is no single right choice applicable to all PE firms. But every firm should deliberate carefully before it chooses, because the direction it takes today will shape the firm’s course for years to come.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to acknowledge the contributions of their BCG colleagues Cristina Henrik, Maarten Bekking, and Eric Ritsema.