Ever since the world’s second merchant set up shop to compete with the first, pricing has bedeviled retailers. The Internet has compounded the complexity by providing consumers nearly complete transparency across retailers, regions, and even national borders, as well as access to any “store” anywhere, anytime. Successive technological innovations, such as the smartphone and tablet, automated price-comparison capabilities, and price-change alerts that track dynamic pricing movements, have strengthened the ability of every consumer to shop like a bargain hunter all the time—without having to expend much additional time or effort in the process. The technology—and its impact on retail—continues to evolve. No one knows for sure what the retail industry will look like in five or ten years, but it is quickly becoming clear that those retailers that do not take steps now to embrace an omnichannel future will soon find themselves severely disadvantaged.

Companies are not without their own resources. Digital technologies offer new and powerful ways to engage with consumers. Retailers have access to more and better tools—principally in the form of an unparalleled breadth and depth of data—than ever before. The trick is determining the role that each category plays in a retailer’s mix and using the right tools to set pricing in line with economics so that customers are encouraged to buy in whichever channel they see as best for them.

As The Boston Consulting Group has argued before, many retailers have not figured out where and why they are winning and where and why they are losing. They have difficulty determining which prices and promotions are working best, and a hard time taking advantage of all the contextual information around transactions that could make a difference in sales. In effect, they know the outcomes of millions of real-time experiments, but they are not able to look at and learn from them. (See “Making Big Data Work: Retailing,” BCG article, June 2014.)

This leads to missed opportunities. And it opens doors to online and direct sellers, which often have better data (or a better ability to use data) and more sophisticated analytics. Many retailers struggle specifically with how to link store and online pricing strategies, and the challenges of selling low-price-point versus high-price-point items. They are unsure how to deal with store zones in a price-transparent environment and unclear on whether or when to match Amazon and other online competitors. They also struggle with distribution economics that make it cheaper to sell low-price-point items in stores, often challenging other stores rather than the online merchants over which they have an advantage. Meanwhile, they risk losing sales of higher-ticket items to online competitors, where the economics favor digital players.

In our experience, many retailers struggle in three areas with respect to pricing: strategy, technology deployment, and organizational decision-making. Some have trouble getting started and fear making costly mistakes. Other rush in, offering discounts without much thought to data or strategy in order to compete with online marketplaces or “pure plays.”

Retailers need to price for the benefit of their business and not be driven by the actions of others—whether brick-and-mortar, online, mobile, or omnichannel players. They also need to harness the volumes of data that they have access to and turn this data into a pricing asset, which requires deploying the right technology and software tools. Establishing clear organizational lines of pricing authority that are designed for an omnichannel world, and instilling the ability to experiment and adjust on the basis of results, should be additional priorities.

This report, a collaboration between BCG and Boomerang Commerce, a leading developer of dynamic pricing technology, provides a roadmap for retailers who want to get it right—pricing that maximizes revenue while protecting margins in an omnichannel world.

Pricing Strategy: Start with Economics and Goals

Pricing today is a multidimensional challenge, but digital commerce is still commerce—profitable businesses still need well-defined strategies rooted in a firm understanding of consumer needs, competitive differentiation, and sound economics. Retailers should take a deep breath and a big step back and look at pricing through two strategic lenses: channel economics and the role of each channel for each category.

Channel Economics, Price Elasticities, and the Need for A/B Testing

Smart multichannel retailers will invest time and effort in understanding the economics and price elasticities of each channel that they use. It is more economical to sell $5 packs of pens in a store than online. Conversely, online retailers have more room to trim margins on high-price-point items, such as a hard drive or a high-end fountain pen. To be sure, the arithmetic becomes more complex when considering customer loyalty, overall household economics, and inventory management. Retailers mastering an omnichannel strategy need sophisticated models that take into account all relevant factors, from price and shipping costs to inventory levels and end-of-season discounting. But the economics themselves are readily evident.

During a three-week period in August 2014, we compared the prices of 31 SKUs in five categories—cleaning supplies, electronics, household paper, housewares, and office supplies—at three retailers: a leading mass-market omnichannel retailer, a large U.S. office supply retailer with a big online presence, and a leading online marketplace. The SKUs covered a range of price points: from less than $10 to more than $100. Overall, the online marketplace was 15 to 18 percent cheaper than the two omnichannel competitors—both online and in-store. But while the online marketplace was the cheapest option for the mid-to-high-priced SKUs, it was consistently the most expensive option for low-priced items—“overpricing” by margins of 20 to 55 percent.

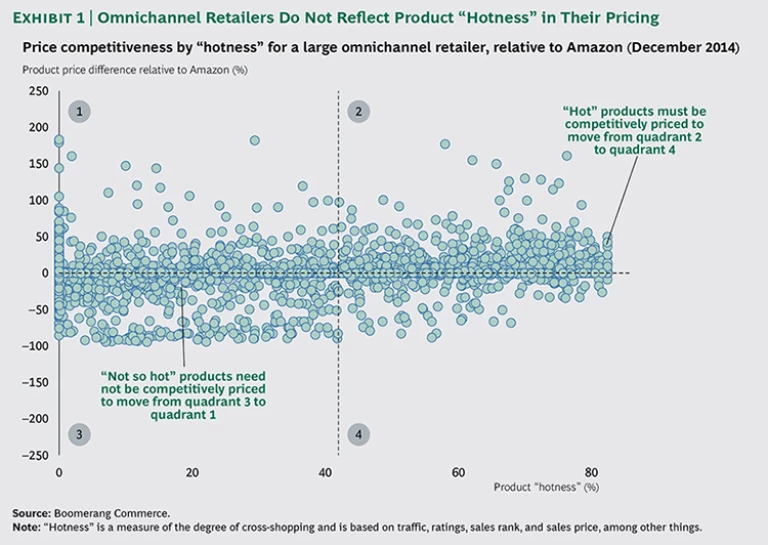

In another analysis, we plotted the price differentials between Amazon and one of the largest U.S. omnichannel retailers for a variety of products based on how “hotly” each product was being cross-shopped by consumers across retailers. (See Exhibit 1.) We found no pattern of the omnichannel retailer taking advantage of products that were not hotly cross-shopped or responding with lower prices to those products that were.

These analyses suggest that omnichannel retailers are not pricing SKUs according to the cost economics of individual channels. Moreover, even in digital channels, retailers are unwilling or unable to determine how competitive they need to be on the basis of consumers’ propensity to cross-shop a particular SKU across retailers. The e-commerce—and m-commerce—marketplaces are still evolving, of course, and as more consumers come to understand how easy it is to check prices across channels on their devices, retailers will need to raise their game to match their customers’ sophistication.

In addition to channel economics, sophisticated retailers will also analyze price elasticity, which operates according to its own dynamics and provides opportunities to boost margins on some SKUs (perhaps at the cost of small margin sacrifices on others). A separate analysis showed that the average price elasticities of demand (PEDs) online and in-store for the ten top-selling white goods (large appliances with a typical price of more than $600) were almost identical—while the average online and in-store PEDs for the ten top-selling white-good replacement parts or accessories (less than $100 in price) varied by more than 100 percent (–1.7 percent online and –3.8 percent in-store).

The PEDs for the appliances were similar because many customers use all channels to shop for high-priced products; their online purchases are influenced by in-store visits and vice versa. Moreover, given that large white goods need to be

delivered, there is no special consideration for free shipping via an online channel. On the other hand, customers shopping for replacement parts are likely to have an immediate need, and those buying accessories have probably just decided to purchase the main appliance. Both sets of customers are much less likely to shop multiple channels—and more often than not these customers are already physically in the store. The online channel cannot meet immediate (same-day) demand, and marketplaces and pure-plays exert no personal sales influence on buyers. As a result, stores have an advantage and can charge significantly higher prices.

There is an important caveat, however. While price elasticities provide a good indication of customers’ price sensitivity, they are determined on the basis of historical data. In today’s evolving omnichannel market, the past is not necessarily a good predictor of the future. Retailers need to combine historical modeling with current testing and analysis to better understand today’s customers’ needs and competitive trends. While it is certainly easier to test and adjust in the online channel, omnichannel retailers can use A/B testing in stores and measure the impact of pricing moves just as online retailers do. They will gain much better causal insights into the effectiveness of their strategies than if they rely only on historical data.

Category Roles and Intent

Retailers need to determine the channel role and intent for each product category that they carry, a calculation that involves multiple factors. Pricing strategy will follow.

No retailer can ignore its competitors, of course, but successful companies do not allow pricing to be dictated by the competition. (If they did, merchants would follow each other around in a kind of circular pricing parade.) Successful retailers will still set clear guidelines on price matching and when to allow inconsistent pricing or promotions between online and offline channels.

The evolution of omnichannel shopping to date shows the role that various categories can play in online and in-store channels. At one end of the spectrum, in categories such as consumer electronics, online dominates, and the traditional store has mostly been put out of business. At the other end, such as car-care products, online has made minimal inroads. In the middle, consumers typically use a mix of online and in-store channels to research and make their purchases, favoring one channel over the other in different instances when it comes time to buy.

Retailers need a clear understanding of the role each category plays, and this drives decisions by category as to where and how retailers play online—and how they ultimately adapt pricing for each category role. In categories where stores dominate, such as stationery, celebrations, home essentials, and car care, retailers will want to focus their efforts on their stores and not make any special effort online, where they should follow in-store pricing.

In categories where most buying takes place in-store but online research is important (kitchenware, garden supplies, and DIY, for example), omnichannel retailers will want to use the online channel to educate and inform, engage social media, and get consumers excited. They should offer the same range of SKUs online as in stores, plus an extended selection, perhaps in premium or niche lines, to gain a variety advantage over their principal rivals. They will want to be the price leader relative to their multichannel competitors and carefully track online pure-plays such as Amazon (using commercial versions of the same price-alert apps that consumers employ) to stay competitive with the online players’ price lead across the full basket of SKUs offered.

For categories where online and in-store activity is truly mixed, the online channel should be marketed as a destination for consumers. In addition to all offline SKUs, the omnichannel retailer should offer an extended variety and selection so that it can claim one of the biggest multichannel offerings. (This might be done through marketplaces such as Amazon’s as well as through the retailer’s own website.) Again, the price goal is to be the leader among multichannel competitors and to stay close to online pure-plays across the full range of items offered.

Smart omnichannel retailers will participate only selectively in online-dominated categories such as consumer electronics, computers, and media. They will put a tight range of products online, with the express goal of supporting their multi-

channel positioning, and they will discount these items heavily in order to reinforce the perception of competitive pricing. They will disconnect online and offline prices and set prices online based on the competition, staying close to Amazon.

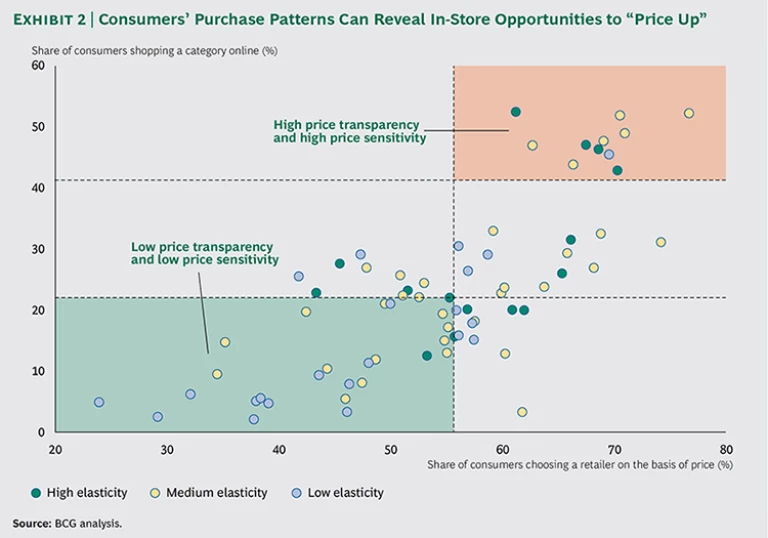

When determining channel pricing, omnichannel retailers should examine consumer purchase patterns to identify categories where they can “price up,” consistent with our earlier discussion of elasticity. (See Exhibit 2.) Particularly in categories with low transparency and low sensitivity, surgical in-store price increases can generate cash to reinvest in building price perception and testing new ways to drive traffic and increase conversion. We have seen some retailers fund their entire pricing program with this mechanism.

Fast-rising m-commerce sales add another dimension to an omnichannel strategy. U.S. sales on mobile devices are expected to exceed $130 billion by 2018. Brick-and-mortar merchants initially decried “showrooming”—consumers comparing prices on their smartphones while in a store—but more recently, smart retailers have sought to turn the tables. Many provide the ability to buy online and pick up in-store. Others offer special promotions to mobile users—again, while the customer is in or near the store—based on real-time data that reveals the customer’s interests and possible buying intentions. The CEO of one of the world’s biggest omnichannel retailers has said that he sees such m-commerce initiatives as an important part of his company’s future.

Technology: Turning Data into an Asset

Most traditional retail-technology systems were built to manage pricing in a brick-and-mortar world. It is no surprise that they tend to march to a well-regulated, predetermined cadence. But the online world has no cadence. Rapid-fire pricing “decisions” are dictated by consumer behavior and by data collected and analyzed in real time by systems and algorithms developed for this purpose.

Traditional retailers have access to much of this same data, both internal (customer transaction histories that can reveal detailed product affinities and promotional and marketing response rates, for example) and external, such as information on competitors’ prices in various markets and channels and product life-cycles. The problem is that much of this data is disparate and unstructured; it needs to be manipulated, combined with data from other sources, and then sifted and analyzed before it becomes useful. Many retailers employ analysts who conduct these tasks manually—meaning that they pursue a distinct process for each category or channel. At one large retailer, we found that 80 percent of its pricing-staff time was invested in the collection and analysis of data and only 20 percent in actually building pricing strategies and models. This is far from an atypical allocation of labor.

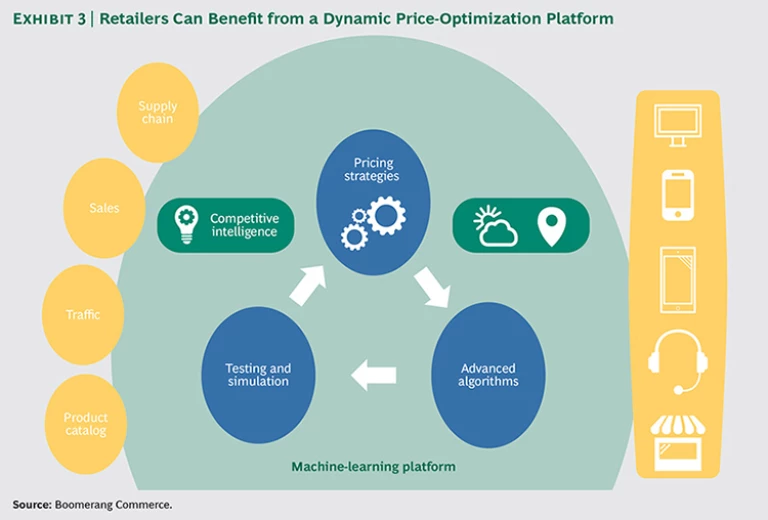

Retailers who want to compete effectively in the fast-paced omnichannel world need to invert this ratio. This requires automating their data collection and analysis with a big data platform that is scalable across channels and business units and will free up as much as 80 to 90 percent of the staff time now spent on basic analysis for improving current strategies and developing new ones. (See Exhibit 3.) The platform not only should help retailers better understand historical data but also should look to the future by enabling companies to rapidly launch, test, measure, and ramp up new pricing strategies. Overall, it should facilitate shorter lead times in the deployment of new or improved strategies.

Acquiring the right technology and software is as important as setting the strategy. Companies can choose to build or buy, but the important consideration is making sure that the system can integrate internal and external data and produce a result that puts actionable information in analysts’ hands across channels, stores, and categories—and frees up time for decision-making. For many retailers, it makes sense to focus time and resources on building pricing-strategy expertise while making use of software-as-a-service products available in the market. An increasing number of these cloud-based tools are in reach of retailers of almost any size.

Organizing for Omnichannel

As we have observed before, omnichannel retailing exposes a number of pain points in a company’s organizational structure. Traditional organizations are not typically set up for omnichannel decision-making. Moreover, merchants or analysts who grew up in the brick-and-mortar world often have trouble with the pace and dynamic nature of the online environment. Establishing parallel teams for traditional and digital channels almost inevitably leads to conflict. Who owns the P&L? If there are multiple P&Ls, which one takes priority?

As e-commerce organizations are formed, we typically see companies following one of two models:

- The brick-and-mortar pricing team replicates one piece of its pricing strategy online, such as using the approach of a single price zone. No dedicated pricing capability is added to the e-commerce team, and e-commerce merchants override brick-and-mortar decisions on pricing as they see fit.

- The e-commerce team builds its own pricing team to assist merchants in setting a separate online-pricing strategy, one that is divorced from the in-store strategy. This model enables the retailer to be more competitive online, but it also risks creating confusion among consumers if online and in-store prices are wildly different, especially in categories that are heavily researched or cross-shopped or if shoppers compare prices with each other using social networks.

As new omnichannel retailers reach the first stage of maturity, the importance of an omnichannel approach to a pricing organization becomes just as significant as other merchandising decisions. A single business leader needs to articulate an overall pricing strategy for the omnichannel experience and to set the rules or guardrails by category for each channel to follow. The execution of these rules depends to some extent on the relevance of dynamic pricing.

For example, retailers in categories that update prices frequently, such as electronics, may require analysts who monitor the marketplace and manage pricing (within set guardrails) using big data software. For retailers in categories in which online is treated as just another zone, more traditional pricing skills may be sufficient. The frequency of updates and the organizational resources necessary to execute them will be dictated by multiple factors, including the category and its competitive characteristics, channel economics, and customer behavior.

Some companies end up with several teams and pricing structures—a merchant team, a pricing team, an e-commerce team, and an omnichannel team. The right answer depends on the level of omnichannel maturity of the company, the category, and the marketplace. Some companies start with different teams, then merge them over time as the online business grows. Others find that establishing separate teams measured against shared objectives and coordinated in such a way as to encourage interaction is an effective approach.

Whatever the model, getting the incentives right is essential. In many instances, incentives are structured to optimize single-channel results rather than to drive overall business, and metrics for omnichannel success are not clearly defined or tied to the overall business plan. Legacy systems do not provide a comprehensive view of customer behavior across channels; in-store and online promotions are frequently out of sync with each other. Many store associates and managers are less prepared for an omnichannel world than are their customers.

Once the pricing strategy and goals are set for the category, the organization should facilitate rapid testing and learning. Ideally, merchant and pricing teams will work together, linked by technology and software, to test and adjust subcategory and SKU group-level strategies on the basis of analysis and diagnosis of real-time results in a cycle that leads to a process of continuous improvement.

Embracing Omnichannel—Carefully

The numbers underscore the need. U.S. e-commerce sales are expected to grow from $300 billion in 2014 to some $500 billion in 2018. M-commerce sales could represent more than 25 percent of this total. Some 60 percent of smartphone owners have used their devices while in a store, and nearly two-thirds expect to do more mobile shopping in the future. Retailers ignore omnichannel at their peril.

But omnichannel complicates pricing—in some cases exponentially. Before they rush headlong into this brave new world, retailers should take the time to do their homework and set their strategy, making sure that they have access to the right data and technology tools and establishing clear lines of authority and responsibility. Then they should walk before they run. The omnichannel world is here to stay. There’s plenty of time to get pricing in this new world right.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to John Bayliss, Thierry Chassaing, and Erin Millman of BCG and Umang Kacker, Mustafa Masud, and Gowri Thampi of Boomerang Commerce for their insights and assistance in the preparation of this report. They also thank Steve Boudreau of BCG and Kevin Reese of Boomerang Commerce for their marketing support.