Dairy is big business—and getting bigger every year. That’s no surprise. It satisfies a wide range of consumer needs, from increased protein consumption and overall health (particularly for growing children) to indulgence foods and even convenience.

Yet as elemental as dairy is, its industry environment is anything but basic. Dairy may be a global industry, but it is also very much a regional one, with a highly fragmented supply. The markets with the greatest growth potential are also the least developed in infrastructure and consumer awareness. Logistics have become increasingly complex. New value-added segments and alternative products have taken off with surprising speed, intensifying competitive pressures and the need to innovate constantly. As if that weren’t enough, major regulatory changes are profoundly altering the operating environment, shifting advantage in many markets around the world.

For even the best and the brightest dairy processors, creating value comes with many challenges. BCG’s in-depth analysis of the dairy market worldwide reveals that creating value today calls for a powerful mix of competencies and discipline. It takes an understanding of the market’s unique characteristics and supply-and-demand dynamics, as well as its daunting operating and regulatory constraints. Success depends as much on operational excellence as it does on identifying the right strategic path to growth.

Dairyland Today: Surveying the Landscape

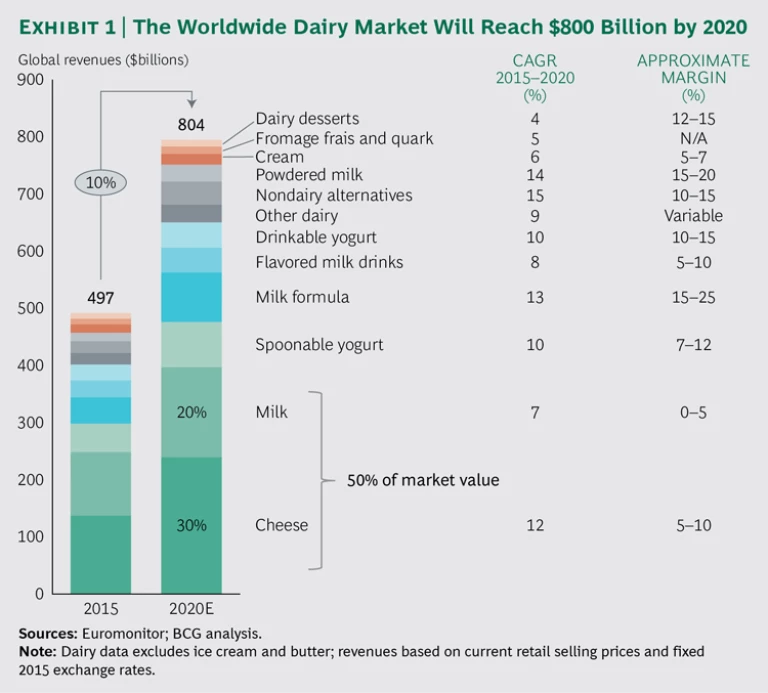

In 2015, with almost $500 billion in global revenues, dairy was the biggest revenue-generating—and the fastest-growing—category in the food and beverage sector. Analysts project 10% annual growth over the next five years, with revenues reaching more than $800 billion by 2020. Milk and cheese will account for 50% of the market, but several value-added segments are also growing robustly. Powdered milk, milk formula, and yogurts, for instance, promise double-digit growth rates. (See Exhibit 1.)

But different product segments yield very different levels of profitability. The key to success in dairy therefore lies in finding the sweet spot of growth and profitability.

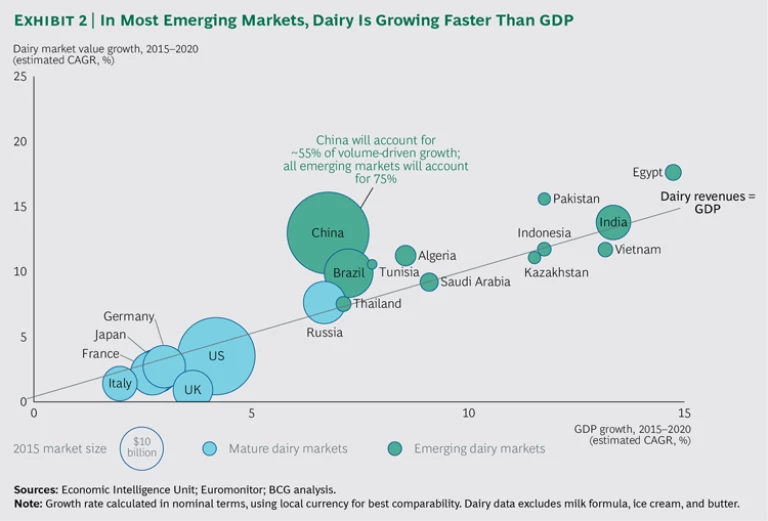

A Bipolar World. Growth across regions is anything but even. In mature markets, per capita consumption remains high, but volume growth is stagnating and in some instances even declining. In emerging markets, however, the picture is just the opposite. Per capita consumption throughout China, the Middle East, and Southeast Asia, while low, is growing rapidly—faster than GDP. Emerging markets are expected to account for 75% of industry growth (by volume) over the next five years. China alone is projected to represent roughly 55% of that growth. (See Exhibit 2.) Although dairy is booming in these nascent markets, the markets themselves are still largely undeveloped, with limited transportation, distribution, and retail infrastructure, and, generally, limited consumer awareness.

Yet even in emerging dairy markets there is bifurcation. India, for example, has a long tradition of dairy consumption—especially yogurt—although production has been local and informal. The means of production and consumption are modernizing as the market evolves toward industrial packaged products and product variety. The Chinese diet and most Southeast Asian diets have not traditionally included dairy, but the indisputable health benefits have encouraged a shift among the past couple of generations to increased consumption.

In this bipolar landscape, dairy production remains largely a local game. Production costs vary widely, and each market is distinct in both milk supply characteristics and consumer tastes. Even within mature markets, these differences loom large: the US and France enjoy trade surpluses (8%), while Japan and Russia suffer deficits (23% and 13%, respectively). In France, cheese rules (at 52% of market value), while in Japan, yogurt predominates (41%). In Brazil, milk tops all segments (79%).

Inherent Complexities, Emerging Challenges. The fundamental challenge in dairy is maintaining quality and quantity within a fragmented supply base. As a perishable, dairy requires more complex operations and logistics—the so-called cold chain—to ensure freshness and safety.

Fast-growing emerging markets pose additional challenges to dairy companies: underdeveloped retail channels and a hard-to-reach rural consumer base. Many companies have found workarounds (such as novel distribution channels) and other solutions (such as ambient formulations, which can be stored at room temperature), but the need for a secure supply and a reliable distribution infrastructure is still strong. And in regions where dairy is fairly new to the diet, consumer demand must be cultivated.

As a commodity, dairy is subject to input price volatility. Raw-milk prices are approaching the record low that they hit in 2009. Since June 2015, they have dropped 25% to 40% in New Zealand, the US, and the EU. This decline has put tremendous pressure on the already slim returns of producers and cooperatives.

Government intervention has a long history in developed dairy markets such as the US, Canada, the EU, Japan, and New Zealand. Subsidies and price supports, production quotas, import restrictions, and supply management systems have traditionally helped keep domestic producers solvent and ensured a safe and steady supply. And the regulatory environment is constantly evolving. The recent abolition of quotas in the EU, as well as trade agreements (notably the Trans-Pacific Partnership), create new opportunities as well as new challenges for producers and processors. (See “Winners and Losers in the EU’s Post-Quota Era.”)

WINNERS AND LOSERS IN THE EU’S POST-QUOTA ERA

Regulation in Europe has been undergoing big shifts. Historically, governments have provided price guarantees and production aids to bolster the dairy industry. But over the past decade, these supports have been replaced with fixed subsidies and subsidies for rural development.

In 2015, milk production quotas, in place since 1962 to discourage overproduction in many of the countries now part of the EU, were phased out. Deregulation was intended to spur industry competitiveness and expand growth opportunities, particularly in global markets such as China and India. So the regulatory environment that helped establish a strong processing industry is now promoting exports.

These changes pose a threat to many in the value chain—especially producers and processors in countries where dairy is less cost competitive. Already, production has been shifting from higher-cost (generally southern European) countries to lower-cost producers in the north, which have more, and more productive, cows per farm. Since 2008, production in northern Europe has increased by 1.3% a year while production in the south has shrunk by 0.2% each year. This trend is expected to continue.

For consumers, the impact of quota abolition is unclear. Retail prices, which differ from country to country, aren’t tied to consumption. Regionally, prices have already become more volatile as they converge with world prices. How long it will take for prices to reach some sort of equilibrium remains to be seen.

The competitive environment, too, is fragmented. There are few global entities, and they tend to be strongest in their home markets. Other market participants include regional companies (frequently cooperatives), cheese makers, large consumer product companies, innovators and niche entities, and health care companies (typically purveyors of infant formula and nutritional supplements). Recently, private-label products, especially milk, have been grabbing increasing market share, while industry outsiders, such as Coca-Cola, are making forays into the sector. And alternatives, such as soy, almond, rice, and coconut milks, are rapidly gaining ground.

How to Create Value in Dairy? The Requisites for Success

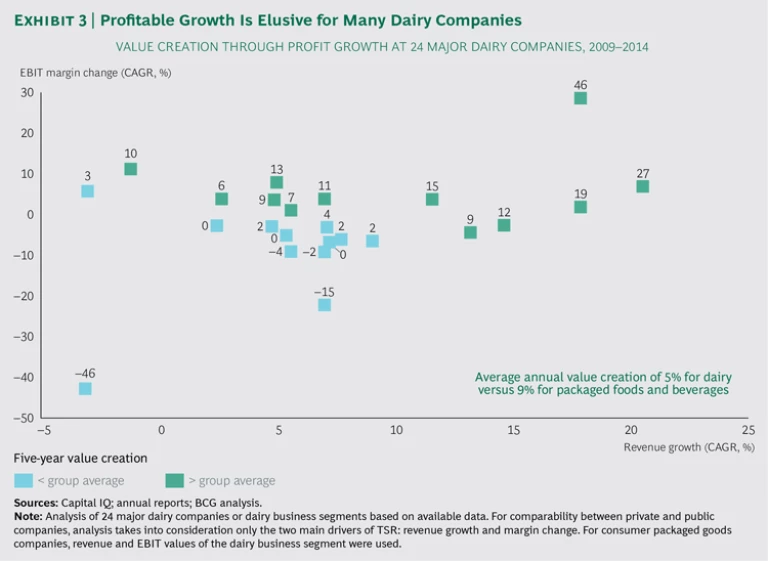

Dairy may be the revenue giant in food and beverage, but it is not the sector’s value creation leader. According to BCG analysis, dairy companies averaged 5% annual profit growth between 2009 and 2014, compared with 9% average annual growth among packaged-food and beverage companies. (See Exhibit 3.)

Given dairy’s many idiosyncrasies, we believe it takes two overarching strategies to succeed. First, companies must have the right table stakes in place: fine-tuned, optimized operations and efficiencies across the entire value chain. In addition, they need a value-creating strategy to set themselves on a course to sustainable growth.

Mastering the Table Stakes

Efficient operations and optimized processes are important in every industry. In dairy, they are table stakes. Moreover, dairy companies need to pursue them across the entire value chain: in their upstream supply management, operations, and go-to-market approaches.

Nail upstream supply management. Perhaps more than any other food product, dairy products’ quality depends on upstream factors, from the very first input (the feed given to dairy cows) to supply variability to cold-chain management to shelf life. Yogurt and cheese, as bacteria-based products, are especially sensitive to quality control. When quality slips or fails outright, the impacts are severe and can hurt both consumers and the brand.

The melamine contamination of China’s milk supply in 2008 caused six deaths and sickened 300,000 babies. That year, China’s leading providers of milk formula saw market share plummet by as much as 40%. The contamination was largely a result of the country’s fragmented and unreliable milk supply. In fact, supply inadequacy plagues many emerging markets. Currently, Southeast Asia must import approximately 60% of its dairy products. Meeting growing demand in the region, as well as in China and India (where demand is projected to outpace supply through 2020), is a major concern.

Sound upstream supply management thus calls for securing a reliable, high-quality supply cost effectively (a special challenge for processors not part of a cooperative). Managing supply quality entails everything from importing powder to instituting rigorous quality controls and training programs. In mature markets especially, it also means keeping close tabs on the complex and dynamic regulatory environment.

Focus ruthlessly on operational effectiveness. Margins in dairy operations are slim, running from 0% to 5%. Considering that milk represents 25% of the value of a dairy company and 50% of its volume, there is little room for inefficiency. Raw-milk prices are volatile, and the perishable nature of dairy gives it a high potential for waste. Add in the costs associated with regulatory compliance, and the need for cost efficiency becomes even more apparent.

We have identified six broad approaches to controlling costs and enhancing efficiency. Each one can deliver as much as 25% savings against the addressable cost base.

- Seek tactical improvements in plant operations, such as by altering layout and improving the flow of materials, boosting equipment and material utilization, improving labor productivity, and enhancing logistics. Such improvements typically yield savings of 10% to 20%.

- Reduce business complexity by shedding less profitable SKUs and standardizing ones that are similar (for example, in size, packaging, or formula). Order-planning improvements, such as reducing wild swings in the timing or size of client orders, are also effective. Companies can wring 5% to 10% savings from such strategies.

- Review the plant network and sharpen the supply chain strategy in any number of ways: consolidating or relocating plants, investing in new technology, expanding scale, even reallocating production among plants. Savings from these measures can amount to between 10% and 20% of costs.

- Hone procurement practices, including negotiation strategies, supplier management, country sourcing, demand management, standardization, process improvement, and make-or-buy decision making. Some companies have saved as much as 25% through this approach.

- Restructure the organization where appropriate, whether in a postmerger integration or in the implementation of shared services. Restructuring can also be done to create new business units, benchmark and optimize the size of functions, or just redistribute tasks. Redesign approaches deliver savings of anywhere from 5% to 15% of costs.

- Deploy digital technologies—robotics in manufacturing, warehouse automation systems, or advanced analytics for forecasting in sales and operational planning—to boost supply chain efficiencies.

Using more than one of these approaches can compound or accelerate the savings. (See “Creaming Costs to Redouble Value.”)

CREAMING COSTS TO REDOUBLE VALUE

Anticipating greater competitive pressure following EU deregulation, Denmark-based Arla has made cost control and efficiencies a long-term strategic priority. In 2009, the global cooperative launched a multipronged effort: adopting lean production programs, implementing new procurement approaches, and revamping its organizational structure.

Exploiting scale has been an important part of this effort. Plant expansion and consolidation have led to greater and more efficient production. (The company’s new fresh-milk dairy, opened in the UK in 2014, is, in its leaders’ view, the most efficient of its kind.) The company also transformed its production structure throughout Sweden. Scale efficiencies are even being sought in new product concepts.

Combined, these efforts have already yielded hefty savings: in 2013 (the first year of implementation) close to €70 million. Just a year later, Arla saved €100 million, or nearly one-third of the company’s EBIT profit of €280 million.

Forge an efficient go-to-market strategy. Because of product perishability (raw milk lasts up to only about 72 hours), every processor’s farm-to-plant-to-retail distribution network must be rock-solid in efficiency. Optimizing the distribution network to ensure that products remain fresh—at the lowest possible cost—is critical.

In emerging markets, product strategy has typically served as a critical workaround in the absence of a cold chain. The market has shifted from powder-based products to ultra-high-temperature (UHT) processed milk, which requires no refrigeration and can travel up to 2,400 miles (4,000 kilometers). In fact, a UHT school milk pack that is distributed nationwide in Thailand and costs 5 baht (approximately $0.15) has helped promote dairy consumption in that nation. Now companies are exploring opportunities to develop and distribute fresh products with an extended shelf life. As consumers increasingly adopt fresh products, shelf life becomes a competitive feature: one company won market share by offering milk with a three-week shelf life rather than the two-week industry norm.

The dominant retail channels for dairy products vary dramatically from country to country. In France and the US, for instance, supermarket-type retailers represent more than 85% of sales outlets. In Russia, modern trade accounts for 65% of the market, and in China and Thailand, 60%. In India, however, only 7% of dairy products are sold through modern retailers, and smaller channels are the main distribution channel elsewhere in emerging markets. Here fragmentation makes economies of scale difficult, and reaching rural consumers and building an adequate distribution infrastructure are a challenge. Companies must choose the proper retail channels to ensure the necessary market penetration—and that means either building infrastructure (say, a cold chain), if necessary, or relying on product strategy. They may also capitalize on relationships and resources available through their involvement in other product categories. (See “How Snacks Paved the Way for Want Want’s Success in Milk.”)

HOW SNACKS PAVED THE WAY FOR WANT WANT’S SUCCESS IN MILK

Taiwan-based Want Want, founded in 1962, began operating in mainland China in 1992. Primarily a snack food maker, Want Want soon recognized the potential for milk in China.

Leveraging its extensive production and distribution network—34 manufacturing facilities, 346 sales offices, and 8,000 distributors—Want Want expanded into ambient flavored milk for children. The company has managed to penetrate traditional retail markets (which represent more than 90% of sales) as well as rural regions, many of them far-flung and with little infrastructure. Indeed, about 45% of the company’s sales are outside of urban centers.

Today, Want Want is investing in a cold-chain supply chain so that it can expand into fresh dairy products. Its powerful brand presence in the ambient market and its ownership of a vast go-to-market network appear to be giving the company a solid start.

In mature markets, a rapidly and widely diversifying retail landscape creates additional challenges and opportunities for the go-to-market strategy. Direct-store-delivery distribution has gained ground for good reason: it’s useful for high-velocity products with a short shelf life, and it allows for more frequent deliveries, premier shelf space, and closer management of sales. For companies willing to pay the premium, direct store delivery can offer important advantages in a sector where innovators are easily encroached upon.

Choosing the Right Value-Creating Strategy

With table stakes secured, dairy companies must determine the strategic course that will enable them to thrive in their chosen markets. BCG has identified four core strategies that companies can adopt to create and sustain value.

Milk opportunities in emerging markets. Considering that until 2020, emerging markets as a whole will account for three-quarters of dairy market growth, companies bent on substantial revenue growth need to seriously consider serving these markets.Value-added dairy products that offer health benefits (such as infant formula and flavored and fortified milks) are in particular demand among Chinese consumers. Although the Chinese have not traditionally been big cheese consumers, consumption is growing in food service, thanks to pizza and burgers. But China’s dairy market remains predominantly ambient, as its cold-chain networks have limited reach. Foreign processors could gain a foothold there by playing up their brand strength and reputation for quality—advantages that resonate with consumers in the wake of recent health scandals.

Generally, success in emerging markets hinges on three possible moves. Companies can insulate themselves from supply interruptions either by importing or by investing in building dairy farms. They can target the largest cities with premium products or invest in building an extensive go-to-market network that penetrates outlying areas—even undertaking such workarounds as reformulating powder products with vegetable fat to preclude the need for a long cold chain. Finally, to compete against leading incumbents, they can invest in branding. Netherlands-based FrieslandCampina has embraced all three approaches to secure market leadership in Southeast Asia. (See “FrieslandCampina: Thinking End-to-End in Emerging Markets.”)

FRIESLANDCAMPINA: Thinking End-to-End in Emerging Markets

With decades of experience building the dairy sector, FrieslandCampina has earned a place as a leader in value-added dairy throughout Southeast Asia. The company’s strategy embraces the three critical aspects of success in emerging markets: bolstering supply quality, building a reliable go-to-market network, and branding.

To ensure steady high-quality inputs, FrieslandCampina applies its knowledge of European suppliers to source inexpensively and profitably from more than 19,000 farmers. At the same time, the company is developing local production. A $30 million joint investment with the agribusiness bank Rabobank is providing subsidies to farmers in Vietnam and Indonesia to buy cows, improve facilities, and fund the installation of biogas units. It will also help train farmers to improve yields and quality.

Simultaneously, FrieslandCampina has invested in developing its go-to-market network, which includes a large roster of mom-and-pop distributors and door-to-door salespeople serving rural Southeast Asia. The company is upgrading infrastructure to help expand its consumer base in urban as well as rural locales.

Now FrieslandCampina is taking its formula for success in Southeast Asia to the Chinese market. Its responsiveness to consumer fears in the wake of the melamine infant-formula crisis has served it well: the company’s Friso infant formula, produced in the Netherlands, continues to grow, despite being substantially more costly than mainstream formulas. To further expand this business, the company recently formed a joint venture with China’s Huishan Dairy to develop a lower-priced domestic infant-nutrition product line.

Still, milking opportunities in emerging markets is easier said than done. The Western companies that have successfully penetrated these markets (such as FrieslandCampina and Danone) did so decades ago, first by importing and later by producing locally. However, over the past five to ten years, local companies have been growing fast and gaining share. Certainly their knowledge of local markets gives them an edge, but it is not the only reason for their success.

Companies such as Dutch Mill (in Thailand) and Vinamilk (in Vietnam) follow a rapid test-learn-refine approach to innovation. With speedier internal approval processes and a willingness to invest in establishing their position over the medium term, these local companies can bring new products to market faster. Given emerging-market consumers’ appetite for new products, demand can be stimulated faster. Foreign producers ought to take note of the benefits that agility has given locals and revisit their innovation and go-to-market strategies—not just for emerging markets but for developed ones as well.

Pursue M&A and strategic partnerships. With growth stagnant in mature markets, companies can pursue mergers and acquisitions and strategic partnerships as a way to grow—in both emerging and mature markets. From 2009 through 2015, several of the industry’s top performers grew through aggressive merger programs. Two of the most successful producers—a leading cheese maker and a European cooperative—more than doubled their annual revenue growth from 2009 through 2014 in this way. Inorganic growth accounted for half of each company’s total growth. And each company generated 10% total shareholder return—twice the industry average.

However, in successful M&A, “strategic” is the operative word. A company’s M&A moves should align with its market strengths, its operational capabilities, and above all, its growth strategy. If you want to be a low-cost producer, for example, divest the niche businesses, which are a costlier distraction. If innovation is the goal, consider losing the commodity lines that will only drag down your margin.

To buy scale, companies must be constantly on the lookout for advantageous strategic acquisitions. Similarly, they must continually reassess their portfolio for divestitures that make both strategic and economic sense. Forging partnerships with companies whose strengths, market know-how, or products are complementary is another important way of gaining entry into a new market or product segment. Coca-Cola’s partnership with Fairlife illustrates the company’s bet to gain a foothold in dairy through a more manageable (that is, ambient) product. Partnership has been a common path to penetrating emerging dairy markets, such as China. For example, a global company can provide its know-how or fine-tuned innovation process, while the local entity brings its knowledge of the local consumer and its market access—or even its agile innovation practices.

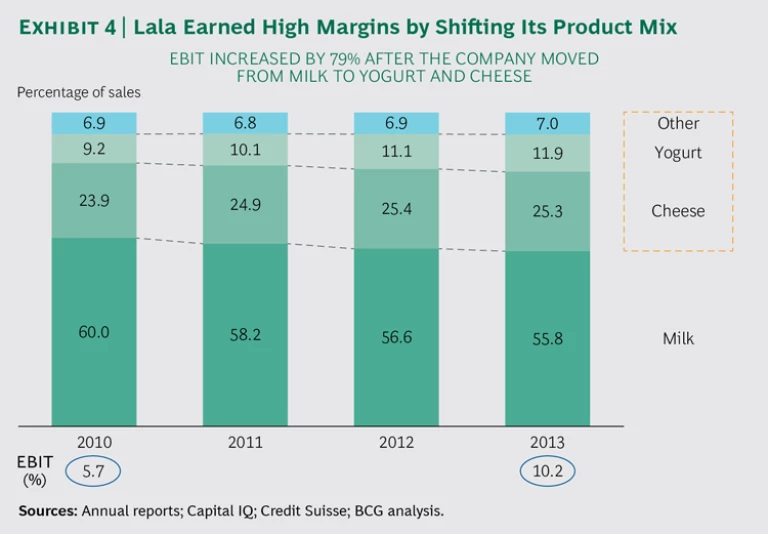

Shift to higher-margin products. Some companies have shifted from low-margin commodity products to focus more on higher-margin segments. In a three-year period, Mexico-based Grupo Lala doubled its earnings by veering away from milk and toward yogurt as well as cheese and other items. (See Exhibit 4.) Companies are also seeking pockets of greater profitability in another way: by shifting from fresh to ambient products (such as powdered or condensed milk), which offer fatter margins.

The margin levels of a given product category vary from market to market. In the US, for example, the coffee and tea segment is most profitable (with an EBIT margin of 20%), while in China, the toddler and kids segment (which excludes infant formula) is highest, with margins of around 16%. Moreover, the profitability levels of a category can shift over time. Leaders need to consider these variations, not only when deciding whether and how to enter a new market but also as they analyze their existing business. To focus effectively on the high-margin areas, it’s important to constantly monitor the portfolio, either by radically repositioning the whole portfolio (as Lala did) or by actively pruning out low-performing products and categories.

Those interested in pursuing this path should keep in mind two caveats. First, they need to redouble their efforts to increase sales in those value-added segments. In addition, they must recognize that this strategy is not sustainable indefinitely. Companies can change their portfolio only so much, and new sources of competition will always be nipping at their heels.

Innovate and seize on new trends. Whether a company wants to create an entirely new product or format or seize on a growing trend, innovation is obviously a time-tested route to successful growth. The rapid growth in several higher-margin subsegments, such as nondairy alternatives, fortified yogurt drinks, and sports nutrition products, demonstrates the potential for innovators and trend spotters. In the coming years, “superfunctional” ingredients that address health concerns (such as weight loss) will likely play a more important role in dairy foods. Combination products, such as milk and juice or milk and grains, are also expected to grow.

Consider the approaches taken by some industry innovators:

- Venturing into New Segments. Switzerland’s Emmi is keen on innovation, including developing new segments. Its ready-to-drink coffee is enjoying double-digit growth rates. Innovation is embedded in the company’s organizational structure, with global process innovation and market insight units reporting directly to the company’s CMO.

- Developing Dairy Alternatives. Denver, Colorado-based WhiteWave Foods, the market-share leader in US dairy alternatives, is keenly attuned to consumer trends. WhiteWave quickly scaled up the production of three acquisitions: Horizon organic milk and Silk soy milk (acquired in 2004 while the company was a unit of Dean Foods) and So Delicious coconut milk (acquired in 2014, after its spinoff from Dean). Horizon’s sales more than doubled in four years. In addition to Horizon and Silk, WhiteWave has built three other leading brands: Alpro (plant-based organic dairy products), International Delight (a coffee creamer), and Earthbound Farm (organic salad greens). WhiteWave’s success in the fast-growing dairy alternative and organic segments has not gone unnoticed; in mid-2016, Danone announced its acquisition of the company for $10.4 billion.

- Innovating in Yogurt. Australian-style yogurt maker Noosa tapped into the “indulgent” yogurt craze and saw revenues skyrocket in just three years. Chobani revolutionized the US yogurt market with the launch of Greek yogurt. The company became an overnight sensation, unleashing consumers’ appetite for the richer, higher-protein form of yogurt that in just a few years has won a 35% share of the US spoonable-yogurt market.

Innovation in dairy cannot be a sometime practice. New products generally hold market share for a year or so before competitive brands arise and begin capturing share. Chobani’s story is an object lesson. Danone quickly followed suit with its own Greek yogurt (Oikos) and nabbed a significant portion of the overall yogurt market. To maintain market share in the Greek-yogurt segment, Chobani launched a raft of new products, including a 100-calorie product, a kids’ yogurt, and a combination yogurt-ancient grains product. In March 2016, the company announced plans to expand its Idaho manufacturing plant (built in 2013) and its original plant in New York to meet its growing production needs.

Companies must treat innovation as a priority—a daily aspiration and constant effort. That means keeping a sharp eye on consumer trends, as well as on market developments, technological and process improvements, and regulatory changes. More than that, it means fostering a culture of innovation, with all the attendant processes and practices. Success also depends on a fast go-to-market cycle, with fast turnarounds. And because imitation is almost inevitable, innovators must be prepared for it, whether they’re launching a new product or investing in existing but fast-growing products.

A Value Creation Checklist

Creating and sustaining value in dairy require both mastering the table stakes and adopting a proven strategy—one that matches a company’s capabilities and goals. Even the most established market leaders understand how fragile success can be. We invite leaders to ask themselves these questions:

- Have we secured a sufficient high-quality supply?

- Are we running our operations as efficiently as possible?

- Could we extend our consumer reach with new distribution channels?

- Do we have a plan to grow in emerging markets and China?

- Are we pursuing appropriate (strategic) acquisition targets and partners?

- How can we optimize our portfolio mix?

- Are we addressing new and emerging consumer needs?

- Are we innovation oriented?

Companies that are not only thinking about but also acting on these questions will be well positioned to turn the promise of growth into reality.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank their BCG colleagues Chloe Marceau-Gosselin, Sebastien D’Incau, Mark Abraham, Waldemar Jap, Oyvind Torpp, Dave Tapper, and Kelli Gould for their contributions to this report. They also thank Jan Koch for writing assistance and Katherine Andrews, Gary Callahan, Kim Friedman, Abby Garland, Gina Goldstein, and Sara Strassenreiter for contributions to editing, design, and production.