US hospitals are rapidly consolidating, and the resulting increase in customer concentration is putting medical technology companies’ traditional commercial model under stress. Many medtech companies are not fully prepared for the changes taking place in purchasing dynamics. Companies that make the necessary moves to adapt—which include developing a top-quality key-account-management (KAM) function—will build a powerful advantage in the near and longer term.

A Market Dominated by Big Health Systems…

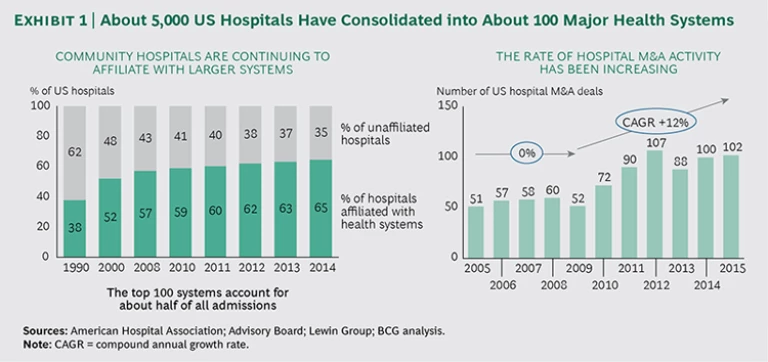

Big, multihospital health systems increasingly dominate the US market, and the rate of consolidation continues to pick up. Some 300 hospital M&A transactions took place from 2012 through 2014, on top of about 220 from 2009 through 2011. An additional 50 deals were announced in the first half of 2015, more than in the first six months of either of the previous two years. Today, the 100 largest health systems account for more than half of all patient admissions, and two-thirds of hospital facilities are affiliated with multihospital systems. (See Exhibit 1.)

Health system consolidation—and the accompanying increase in the centralization of purchasing decisions—will continue because the financial and clinical benefits of consolidation are compelling. Greater market share puts large health systems in a stronger negotiating position with private payers and vendors all along the supply chain, including medtech companies. Their financial scale enables capital investment in technology and infrastructure that smaller systems simply cannot afford. Increased clinical integration within large systems is expected to improve care coordination, paying dividends via better patient outcomes and greater transparency.

These large health systems are changing where and how vendors are selected. Medtech companies need to shift their focus—and their resources—to multihospital systems. Most medtech companies will (and should) continue to negotiate with group purchasing organizations (GPOs) to ensure that they have contracts in place and access to GPO members. But in most product categories, health systems are more important than GPOs. Selling successfully to these organizations requires a deep understanding of their strategy, stakeholders, and decision-making processes. Only with this understanding can medtech companies customize value propositions to meet the needs of sophisticated health system customers. Building an account team with this kind of in-depth customer knowledge requires an exceptional degree of coordination across a vendor’s selling resources.

…Puts the Traditional Medtech Commercial Model Under Stress

As hospital systems consolidate and centralize decision-making, medtech companies’ largest customers account for an ever-increasing percentage of revenues, profits, and purchasing leverage. In this environment, the traditional medtech commercial model is no longer sufficient. Medtech companies must come to terms with five evolving realities.

Big health systems are increasingly national, while medtech sales forces are predominantly regional. One company we worked with recently had approximately 250 sales reps, spread across five business units, calling on a single health system’s 100 facilities. Worse, very few of the salespeople had any idea of their company’s overall strategy for the customer—or the health system’s strategy for its network. Medtech companies need to coordinate their commercial resources and execute sales strategies that are based on a company-wide understanding of each customer’s needs.

Centralized systems drive standardization and compliance across multihospital networks. Large health systems are developing new ways to leverage their purchasing power over medtech vendors. They are involving physicians in purchasing decisions and linking compensation incentives with cost control. They have adopted software platforms that make it easy to see how much they pay for various products. They know how much volume they do with each vendor in individual facilities and across the system. Health systems are also centralizing their supply chain function to increase system-wide control and standardization.

Traditionally, medtech pricing and contracting strategies have been developed and executed at the local level, which has often resulted in significant inconsistencies within large health systems. A multihospital network often knows more about its system-wide dealings with a particular vendor than the vendor knows about its customer, which can result in uncomfortable business reviews and awkward negotiations. A multistate for-profit health system will not react well to learning that a tiny “St. Elsewhere” hospital has been getting a better price for knee implants.

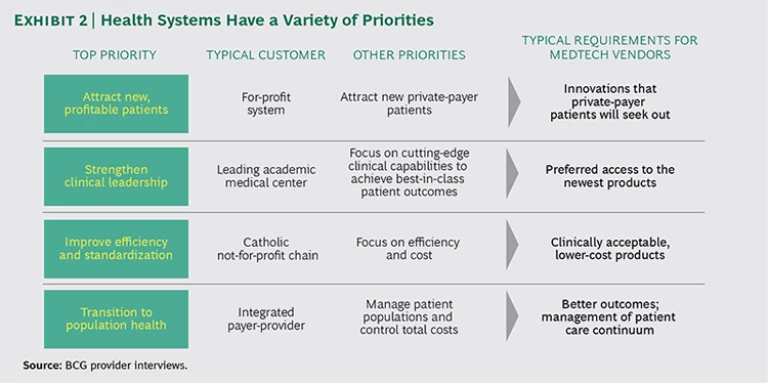

Each health system has its own priorities. US health systems vary widely in size, geographic footprint, strategy, and mission. On the surface, most large systems have similar priorities—attract new patients, strengthen clinical leadership, improve efficiency, and make the transition to population health—but the degree of importance that each system assigns to each priority varies substantially. The differences have significant implications for medtech providers. (See Exhibit 2.) For example, an integrated payer-provider might appreciate the ability of a novel cancer-diagnostic device to more effectively manage clinical outcomes and the cost of treatment, while a for-profit chain may be more intrigued by the device’s ability to attract new patients.

Traditionally, the medtech industry has struggled to create customized selling strategies and value propositions to serve different customers and their needs. Medtech companies need to master this approach to achieve best-in-class KAM.

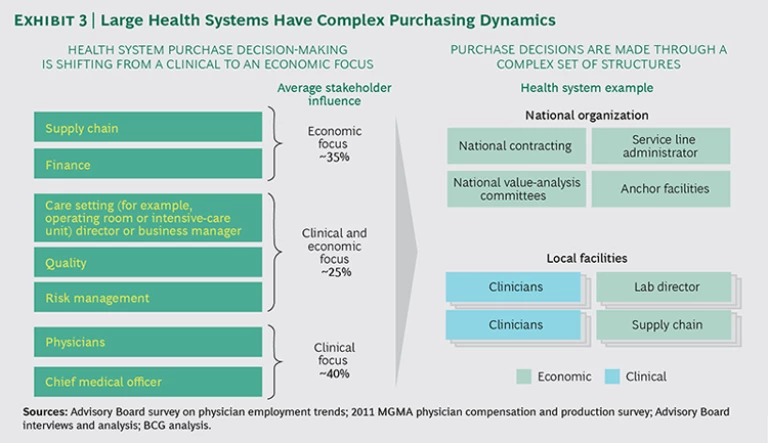

Centralization of purchasing is on the rise, but the structures and processes vary. The shift of purchasing authority for medtech products from clinical to economic decision-makers is well recognized. Less well understood are the structure and hierarchy in which purchasing decisions are made at each large system and the often complex role of national, regional, and local value-analysis committees.

Health systems differ materially in their degree of centralization. Some systems make big purchase decisions at the center, some delegate to regions, and some use a hybrid approach, with individual facilities making decisions on the basis of center-provided guidelines. (See Exhibit 3.) In our experience, medtech account teams typically underestimate the value of understanding these complex structures and their influence on decision-making results. One real-world example of how this lack of understanding can play out: an imaging-device company devotes its commercial resources to selling to facility-level radiologists and administrators—only to have their recommendation overturned by the corporate vice president of capital purchasing.

Health system value-analysis committees rank clinical value over clinical preference. Value analysis—measuring the benefits of a device relative to its cost—has resulted in more informed and more economically sophisticated decision-making in large systems. Physicians are increasingly “picking their battles” instead of fighting hard for every clinical preference. Overall, hospital systems are less willing to pay for “incremental” innovation. Medtech companies now more than ever need to demonstrate the value of their products. This means marketing on the basis of economic benefit (lower waste, increased efficiency, or reduced length of stay, for example) as well as on clinical advances (such as higher survival rates or fewer complications). Suppliers must articulate a comprehensive set of benefits that stresses the ability of a product or solution to add value across multiple dimensions. Failure to do so will consign medtech companies to selling commodity products and competing on price or volume.

A New KAM Model: From Sales Transactions to Strategic Partnerships

On the basis of our work with medtech companies, we have identified six KAM strategies that, taken together, can transform transactional customer relationships into long-term strategic partnerships rooted in mutual value creation.

Develop customer-specific account plans that are built upon deep customer understanding. Best-in-class account plans reflect a deep understanding of a customer’s business strategy and objectives—and extensive knowledge of the customer’s purchasing process and key decision makers.

The challenge for medtech account teams is determining where the purchasing authority resides in each system’s structure and understanding what factors those decision makers care most about. Good account plans use this understanding, as well as a detailed analysis of the customer’s market position, market share, and growth prospects, to help articulate a clear sales strategy and how that strategy will help the customer achieve its objectives. Periodic reviews, especially after a significant customer event such as a merger, acquisition, or senior-management change, help keep the sales strategy fresh and relevant.

Develop clear economic and clinical value propositions for core products. Medtech suppliers need to demonstrate the value that their products can deliver beyond price and clinical efficacy. Potential proof points are improving outcomes, increasing workflow efficiency, requiring fewer staff, reducing infections, adding new profitable patients, reducing readmissions, and many more. Companies need to invest in developing a comprehensive sales pitch and arming account teams with the strongest possible marketing materials, including “calculators” developed for each large health system that show how the supplier’s products deliver value—and how much value the customer can expect. Medtech companies also need to develop reference accounts that they can use as examples to help other customers see the value of solutions and products.

Adopt a consistent and defensible national pricing and contracting strategy. Smart medtech suppliers put pricing discipline at the forefront of their sales efforts and support it with the right tools. In our experience, the two key enablers are strong pricing governance and a pricing team trained to broaden the conversation beyond a narrow focus on what a customer will pay for a particular device.

Strong governance starts with the establishment of a multidisciplinary pricing committee that includes sales leadership, product managers, and marketing representatives to provide clear pricing oversight. Unambiguous thresholds should trigger reviews of proposed pricing exceptions by the committee. Disciplined companies sidestep pricing predicaments, such as when a small hospital receives better unit pricing than a large health system, by basing pricing on anticipated business volume from a customer and the share of product category spending levels that the customer is prepared to commit to over time. Disciplined companies also ensure consistency in prices offered across large systems (including those that span several states or regions) to avoid selling the same products at different prices to the same customer—a sure road to damaged customer trust.

In addition, successful medtech companies expand pricing negotiations beyond the average selling price and add value to the customer and the relationship. Depending on a key account’s priorities, these may include rebate programs (on specific products or across the portfolio), payment conditions, risk sharing, outcome guarantees, and value-added services.

Following these recommendations will result in a sustainable pricing strategy for key accounts; nonetheless, increasing price transparency leaves most suppliers with some degree of risk associated with legacy pricing. We recommend that all companies conduct a detailed audit of their pricing strategy in order to quantify this risk and develop a concrete set of steps to minimize it over time.

Implement a sales coverage model that defines clear roles for key account managers and sales reps in the field. Many medtech suppliers have KAM teams made up of account managers who are primarily focused on pricing and contract negotiations with a hospital system’s supply chain organization, sales reps who cover physicians and individual facilities, and clinical specialists. Best-in-class KAM requires the account team to work together. To make this model work, the roles and responsibilities of each position must be clearly delineated.

The critical KAM position, of course, is the account manager herself. She is responsible for the overall strategy for the account, for building and maintaining strong customer relationships at the health system’s corporate center, and for directing and supporting selling activities in the field.

The most effective account managers pursue a broad set of relationships with senior clinicians, administrators, and supply chain professionals throughout the health system. A detailed understanding of the customer’s strategy enables the account team to develop an account strategy that brings tailored solutions to best meet customer needs. The account manager then directs the selling activity for the account, relying on robust two-way communications between the manager and local selling teams to ensure consistent sales execution. Regular meetings, feedback mechanisms, and shared account plans help facilitate this process.

The most progressive medtech companies are beginning to vary their sales coverage on the basis of customer characteristics. Examples we have seen include:

- Replacing traditional sales reps with a key account manager supported by clinical specialists for highly committed accounts

- Varying the “bag configuration” (the selection of products that sales reps carry) according to the vendor’s share in a large account or system

- Forming a ten-year committed partnership between the medtech company and a health system

Build a KAM team that possesses a new set of skills. KAM teams today must actively manage the full customer relationship, including strategy development, active coordination across sales teams, product and price negotiation, and maintenance of strong customer relationships at the health system center. In addition, KAM teams are best positioned to develop partnerships with customers on nonproduct services and solutions and risk-sharing arrangements, which for many medtech companies are critical levers for strengthening customer relationships.

Medtech teams today need a very different, and much more comprehensive, set of skills—including expertise in business planning and strategy, negotiating and contracting, and coordinating resources across a large organization. These are skills that few traditional medtech sales teams possess. Most medtech companies will need to add talent outside of traditional clinical selling roles, develop clear competencies that reflect the KAM strategy, and actively monitor KAM performance against those competencies.

Provide the team with management tools that support efficient decision-making and cross-functional sales execution. Medtech suppliers need to augment their KAM teams’ toolkits with the resources that facilitate more complex account management. These tools include dashboards that accurately break down financial performance by health system customer and that highlight activity at the facility level, customer relationship management tools that track key clinical and economic influencers for an account and indicate ownership of each relationship, deal calculators that provide a clear view of the total profitability of any given transaction for the vendor, and up-to-date mapping capabilities that efficiently distribute targeted communications and strategic updates to all internal sales resources deployed to hospitals within a system.

A Medtech KAM Checklist

Making the transition from a traditional medtech sales model to an effective KAM strategy requires a thorough rethinking of clinical strategy, organization, capabilities, tools, and enablers. Medtech companies can assess their readiness to make the change, or their progress if they have already started, using the following checklist in each of the six key areas described above.

- Account Planning. Has the company adequately invested in understanding its key customers’ individual needs and business priorities? Can the KAM teams articulate what is on each health system CEO’s agenda? Is senior management demanding the necessary level of detail from KAM teams as part of the account-planning process? Does the company have account-specific strategies for its largest health system customers?

- Economic and Clinical Value Propositions. Has the company thoroughly assessed the economic value of its major products and quantified it for its biggest customers? Does the company have tailored marketing materials that describe how its product and solutions deliver economic as well as clinical value to customers?

- Defensible and Consistent Pricing. Is the company selling the same product at different prices to multiple facilities within a health system? Are pricing levels defensible—on the basis of volume, commitment, and contract duration? What are the revenues at risk from different prices for the same products within a single integrated delivery network or system?

- Sales Coverage Model. Do the company’s KAM teams have the credibility and authority with divisional and regional sales leadership to shape account-level strategy? Has the communications and governance infrastructure been put in place to convey account strategies to the full KAM team? Are the appropriate incentives in place to encourage and reward cross-business-unit collaboration?

- KAM Talent Management. Do KAM leadership and KAM teams have the right skills for complex selling arrangements? How deep is the talent pipeline for KAM leadership? Is the company succeeding in identifying, retaining, and developing its KAM talent?

- Management Toolkit. Can KAM teams—and senior management—measure the success of each key account in an accurate and efficient manner? Has top management defined in a measurable way what success looks like account by account?

The trend toward consolidation among US hospitals will continue. Pressure on the traditional medtech commercial models is unlikely to abate. Companies that move to a KAM approach—and ensure that each KAM team has the right leadership, staffing, and resources—can strengthen strategic partnerships with their largest health system customers. A well-developed KAM capability brings advantages to the medtech company and economic value to the customer.