Since 2010, the mining sector has experienced a sharp drop in TSR, leaving investors skeptical about its future. A price recovery in 2016 brought a sigh of relief from mining companies. But much remains to be done to win back investors’ confidence after a decade of subpar returns.

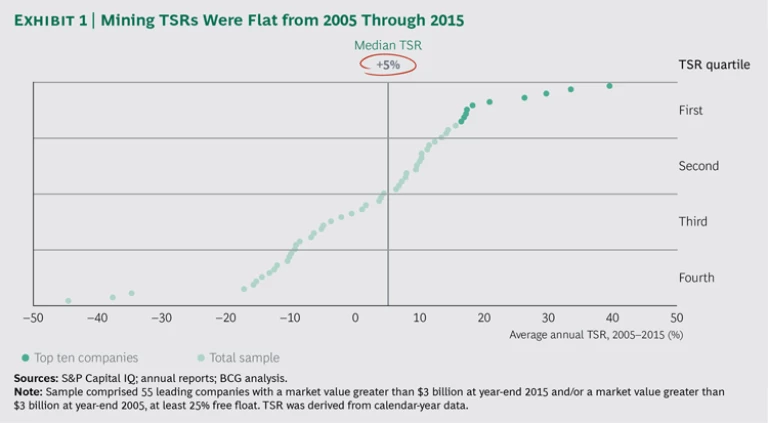

The Boston Consulting Group analyzed the performance of 55 leading mining companies from around the globe from 2005 through 2015. We found that these companies delivered a median annual TSR of just 5% during that period, lagging behind the S&P 500’s 7.3%. (See Exhibit 1.)

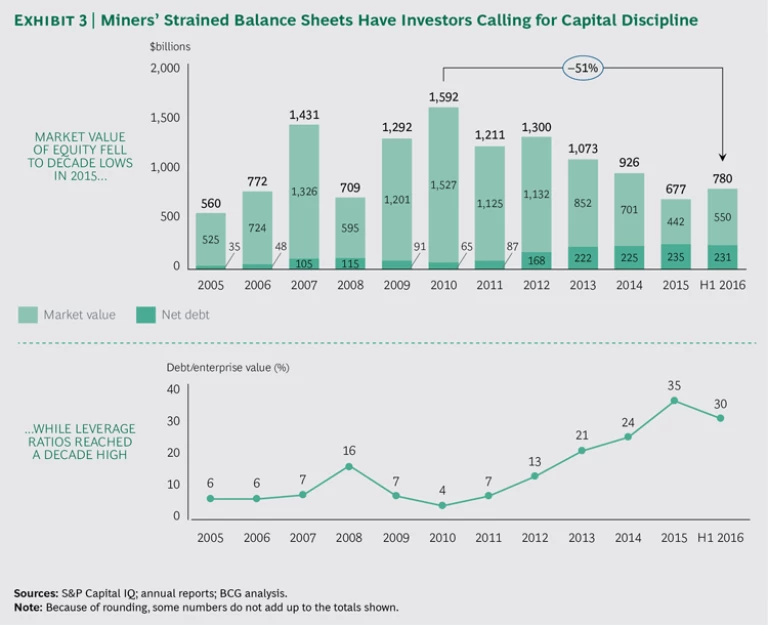

The downswing has hit companies hard, halving the overall sector’s market value. In response, companies have pursued multiple programs aimed at cutting costs and boosting productivity, but the sector is still not back on a solid footing. Many companies worldwide remain heavily indebted, with the highest leverage ratios in a decade. Returns on gross investment haven’t improved over the preboom lows. And capital expenditures are still elevated.

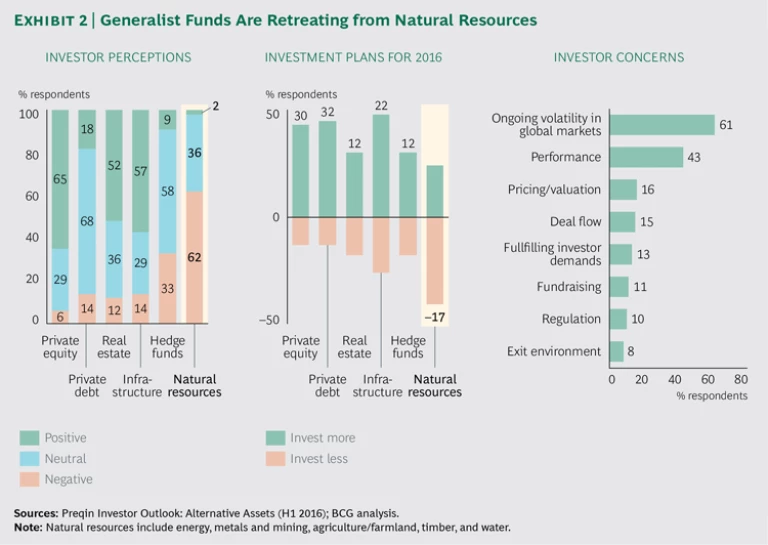

Meanwhile, skeptical generalist investors have reallocated billions in capital away from natural resources. (See Exhibit 2.) And in some regions, pressure from activist investors has intensified.

To win back investors, management teams must take the following steps:

1. Address balance sheet concerns.

2. Re-earn the right to grow.

3. Develop a compelling path forward.

Each company must first determine exactly where it stands. Owing to heavy investments made during a time of record-high commodity prices, the industry has splintered into three groups: the haves, the stretched, and the distressed.

The haves are in relatively decent shape, with low-cost operations and a fairly steady cash flow stream. The stretched are grappling with challenging cost positions and/or debt pressures. And the distressed are struggling to stay afloat after seeing prices fall below their operating costs. Stretched and distressed companies need to concentrate on the first two steps before appealing to investors to support a progrowth agenda.

Addressing Balance Sheet Concerns

While capex has declined from its 2012 peak, such spending remains elevated relative to cash flow from operations, limiting the cash available for distribution to shareholders. As a result, miners’ balance sheets have become increasingly strained. (See Exhibit 3.)

Assuaging Generalist Investors’ Concerns. To reassure generalist investors that they are committed to addressing their balance sheet problems, mining companies should develop a financing plan that can withstand a range of market scenarios—including swings in commodity prices, input costs, and foreign-exchange rates. Savvy moves include the following:

- Renegotiate financial obligations. For instance, extend debt repayment schedules further into the future to reduce the immediate cash crunch.

- Creatively monetize noncore assets. These can be mineral assets that no longer fit with a company's strategy; nonmineral assets such as equipment, infrastructure, rights, and permits; or noncore infrastructure assets such as power stations and ports. A growing pool of capital is available for such purposes as royalty and streaming arrangements for mineral properties and sale and leaseback deals for infrastructure.

- Smartly reduce capex needed for growth projects and current operations. Miners can do this by eliminating capital projects altogether (or at least delaying them) or by rethinking projects and the capital required to complete them. Companies with healthier balance sheets may also be able to inexpensively advance future growth projects through their evaluation processes, assessing deposits for eventual development or sale.

- Aggressively minimize working capital needs. For instance, miners can renegotiate supplier and customer terms and reduce inventories throughout the value chain.

Preparing for Activist Investors. Perhaps not surprisingly, activist investors have responded to miners’ financial difficulties by increasingly targeting these companies for aggressive reform. This is especially true in North America, where shareholder activism is well developed.

To prepare for possible attention from activist investors, miners can proactively perform a do-it-yourself “health check.” Such an assessment requires that they scrutinize themselves through the eyes of an activist, considering the kinds of steps that activists might take to unlock value at their company. (See “Do-It-Yourself Activism,” BCG article, February 2014 .) Asking these questions can help:

- Have we developed an analytics-based investment thesis? Activists focus less on top-line growth, earnings per share, and profitability than on value per share and a company’s balance sheet. They dispassionately challenge the logic of owning noncore operations and consider all structural alternatives. Management must do the same.

- Do we use our balance sheet wisely? Miners must actively manage the tradeoff between reinvesting cash to drive profitable growth and distributing it to shareholders. Companies will have different value creation priorities, and the way they manage this tradeoff—investing heavily to drive advantaged growth in the core business versus creating value through restructuring or asset liquidation, for example—has implications for their capital requirements. But one thing is certain: failure to manage the tradeoff effectively attracts activist attention.

- Have we acknowledged and closed significant performance gaps? Miners need to understand and address shortfalls in the quantitative metrics that activists use to identify potential targets—valuation discounts, historical TSR, cash and operating margins, and balance sheet profiles—as well as industry-specific operating metrics and qualitative performance measures.

- Do we engage with our owners openly and candidly? Mining companies’ senior executives need to meet regularly with top investors to determine what they see as the company’s important value creation opportunities. Activists are less likely to intervene and succeed if they lack the support of major institutional shareholders.

- Have we built an ownership culture and a value-adding board? The right performance metrics, transparent performance assessment methods, and rewards tied to value creation in both the short and long term will help miners make good on their investment thesis, further discouraging activists from targeting the company.

Re-earning the Right to Grow

To re-earn the right to grow, miners must supplement existing initiatives with efforts aimed at pursuing the next level of productivity improvements. The following approaches can help:

Optimize the full value chain. By taking an integrated view of the value chain and making real-time adjustments to different parts of it—such as resources, customers, contractors, overhead, and support functions—miners can unlock significant additional potential. For example, they can rebalance the asset production mix to enhance ore grade and reduce costs by automating control systems.

Optimize mine plans for value creation. Miners must test and optimize major tradeoffs in their mine plans, such as cutoff grades versus mine lifetime, to ensure that their sites are pursuing a path toward optimal value. They should also test the sensitivity of their plans to variables such as recovery, foreign-exchange rates, and assumed discount rates. These measures will allow them to make more informed decisions about where to operate (for instance, how much volume to draw from specific mines), when to operate (for example, whether campaigning versus continuous operation is preferable), and how to operate (for instance, whether an owner operation or a contractor model is best).

Improve productivity continuously. Companies that excel at continuous productivity improvement do so by articulating clear objectives that are driven by top leadership, defining new ways of working that motivate the desired behaviors, conveying a sense of urgency, and excelling at execution.

Aggressively commit to applying technology. Deployed effectively, data generated by a company’s many processes and operations offers tremendous potential in critical business decision making and in the identification of cost reduction and productivity improvement opportunities. For instance, predictive analytics and structured and unstructured data from multiple databases can be used to generate statistics on work orders (such as execution efficiency and preventive versus corrective measures), identify the root causes of production losses, determine the optimal frequency of preventive maintenance by equipment type, and calculate the number of crews and crew movements needed to minimize production losses. Dynamic simulation modeling can allow miners to inexpensively pressure test, de-risk, and quantify the potential impacts of improvement initiatives—such as the debottlenecking of existing or planned operations.

Developing a Compelling Path Forward

For companies that have addressed their balance sheet issues and re-earned the right to grow (or have maintained resiliency despite the down cycle), now is the time to think about how to create new value in the future. But it’s not enough to be a so-called great company by occupying a leadership position in the industry or enjoying the advantage of strong assets. Miners must also strive to be a great stock—that is, capable of delivering sustainable and attractive value creation in the form of rising TSR.

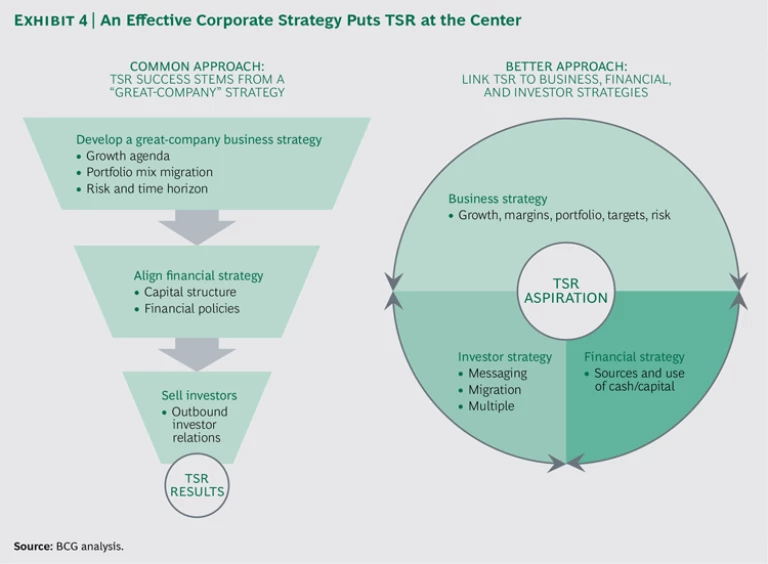

Meeting the Great-Company/Great-Stock Imperative. Many companies focus too much on being a great company, viewing TSR as simply the end result of their strategic efforts. They craft a great-company business strategy, including a growth agenda, a portfolio strategy, and risk management efforts. They then align their financial strategy, including the capital structure and requirements and financial policies, with the business strategy. Finally, they pitch the plan to investors with the expectation that successful TSR results will follow.

To be both a great company and a great stock, miners need a more explicit and cohesive value creation strategy. Formulating such a strategy starts with defining sensible TSR targets that take into account the profitability of a miner’s assets through the commodity cycle and the expected range of commodity prices. Moreover, the value creation strategy should connect the TSR target with three other strategies. (See Exhibit 4.) These are:

- Business strategy, including how much to focus on growth versus yield plays

- Financial strategy, such as how to fund existing operations while also creating funding options for future growth

- Investor strategy, including who the company’s ideal investors are and how it plans to attract and retain them

Using TSR to Evaluate Strategic Opportunities. Integrating their business, financial, and investor strategies with their TSR aspirations will allow miners to more easily evaluate the various strategic opportunities open to them. They can also test their assumptions about their base-case business plan and the impact of different strategic moves on their share price. The resulting insights can help them focus on the moves that will best help them reach their desired TSR.

This approach differs markedly from the one that many companies use in that it provides a common yardstick—TSR—for assessing all the strategic opportunities open to a company. TSR is the ultimate measure of how the market evaluates a company’s performance. By putting the potential impact on TSR at the center of its evaluation of potential strategic moves, a company incorporates the viewpoint of investors into its strategic thinking.

Miners that use this approach stand a better chance of building up healthy supplies of capital and cash, as well as enhancing their strategic and financial flexibility. As a result, they can position themselves to act countercyclically by taking advantage of depressed prices for assets, equipment, and talent at a time when buyers are scarce.

In an environment of shrinking TSR and eroding market value, mining companies cannot let themselves be distracted or deceived by the uptick in commodity prices that sparked optimism for some in 2016. The price recovery masked persistent challenges still facing the sector, as investors’ continued rechanneling of vast volumes of capital away from mining confirms.

To survive, miners will need to put the restoration of investor confidence at the top of their strategic agendas. For those already in good shape financially, developing a compelling path forward and a solid investment thesis should be the focus of their transformation efforts. This can help miners show investors that they have a plan for creating value and that they intend to do more than just rely on recovering commodity prices.

For miners in not-so-good shape, addressing balance sheet issues and re-earning the right to grow must come first. Only then will they be able to build the credibility and momentum needed to develop a compelling path forward and a solid investment thesis.

But regardless of where they focus first, mining executives will need to rethink major elements of their enterprise—including how they craft corporate strategy and what their business model looks like. Hard work, yes—but essential for surviving (at least) and thriving (at best) in today's challenging environment.