To capture the immense opportunities in emerging markets, pharmaceutical companies require highly targeted strategies. Each country presents a unique set of socioeconomic and geographic characteristics, government and regulatory issues, and local competitors. And what works in developed markets won’t necessarily work in emerging economies.

The payoff for getting a targeted emerging-market strategy right is significant. By 2020, emerging markets will account for more than 30% of pharmaceutical sales growth worldwide. It is crucial for pharma companies to tap into this wellspring of growth as health systems mature.

Southeast Asia alone is expected to generate $40 billion in pharmaceutical sales by 2020. The diverse countries in this region can serve as case studies to help companies develop strategies for success in other emerging markets.

For those looking to build a presence in Southeast Asia, branded generics can serve as an ideal entry point. These off-patent products, sometimes produced by manufacturers other than the originator of the patented product, use the same active ingredient as that product and are intended for the same treatment purposes. But they typically command higher prices than unbranded generics because consumers, particularly those in emerging economies where quality assurance remains low, are willing to pay a premium for drugs sold by well-known and trusted brands. Branded generics thus create value over the short and medium terms and serve as a springboard for long-term opportunities. But to succeed with this kind of targeted strategy, multinational corporations (MNCs) must be exceptionally well focused.

The Opportunities and Challenges in Southeast Asia

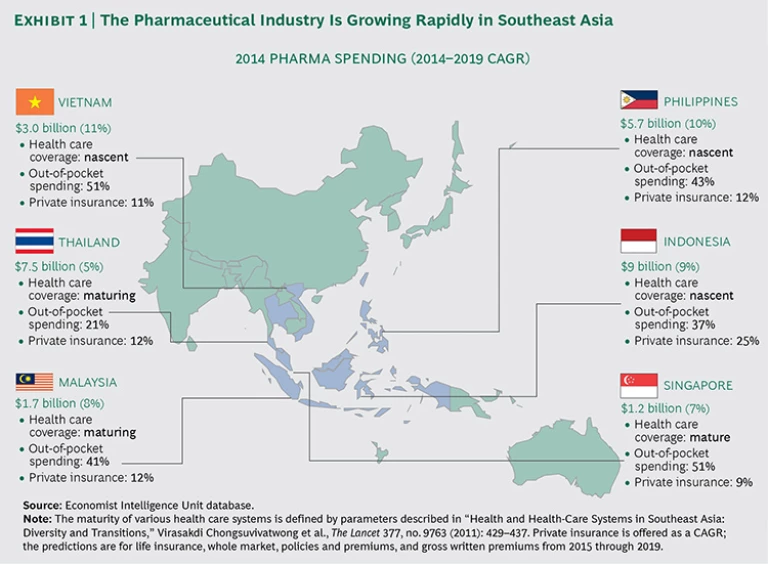

The pharmaceutical sector of the health care industry in Southeast Asia has seen strong growth in recent years, fueled by an expanding middle class, a rise in personal income (an estimated 6% CAGR from 2015 through 2030), and a surge in private insurance coverage. (See Exhibit 1.) In addition, less healthy lifestyles have led to an increase in costly, chronic disorders, such as cardiovascular disease and diabetes. To meet these growing needs, governments are making long-term investments in their health infrastructures. Indonesia, for example, launched an ambitious plan to extend health care coverage to 100% of its population (nearly 240 million citizens) by 2019.

Robust market opportunities exist in Southeast Asia, but MNCs will also face challenges:

- Varied Competitive Dynamics Across Countries. Local competition in Southeast Asia varies considerably from country to country. In Malaysia, MNCs represent 80% of the pharmaceutical market, whereas in Indonesia they account for just 15%. The dominance of local competitors varies as well. In the Philippines, the largest local company commands 30% of the market, while the largest local competitor in Vietnam owns just 5% of the market. Many of these local competitors have a distinct advantage over MNCs, particularly if they have large distribution networks, direct access to physicians and retailers, and strong brand recognition across a broad product portfolio spanning therapeutic areas.

- Pricing Pressures. MNCs face intense pressure on pricing because of local, unbranded generics, which are generally very inexpensive. In many cases, this disadvantage for MNCs is intensified by protectionist policies that favor domestic producers over international exporters. Vietnam’s Ministry of Health, for example, launched an initiative to ensure that domestic pharmaceutical companies meet 70% to 80% of domestic demand by 2020, a move that will hamper MNCs’ efforts to expand their geographic footprint.

- Immature Infrastructure. Despite efforts to boost national health budgets, the lack of basic health care infrastructure in some Southeast Asian nations poses considerable challenges. Indonesia has just 0.3 doctors and 0.6 hospital beds per 1,000 inhabitants, and many of its public health facilities in rural areas suffer from a lack of equipment. In the Indonesian province of Nusa Tenggara, 64 hospitals serve a population of 9.9 million—and the province’s complex geography and underdeveloped transportation system pose significant barriers for patients trying to access health care services.

To tackle these challenges, MNCs need to make smart decisions about how to tailor their offerings to meet the specific needs of a given market. In our view, the most successful companies will pursue a multiphase approach, starting with branded generics.

Unlocking New Markets with Branded Generics

Quality assurance for pharmaceuticals is a serious concern in emerging economies. The World Health Organization estimates that counterfeit drugs constitute 10% of the world’s drug trade and represent one of the fastest-growing gray markets. Further, according to the United Nations, criminals earn $5 billion a year peddling counterfeit pharmaceuticals in Southeast Asia and Africa.

With the sharp rise in the trafficking of counterfeit products, consumers in emerging economies began to express concerns about the efficacy and safety of these drugs. Major pharmaceutical companies started manufacturing branded generics in response to these concerns.

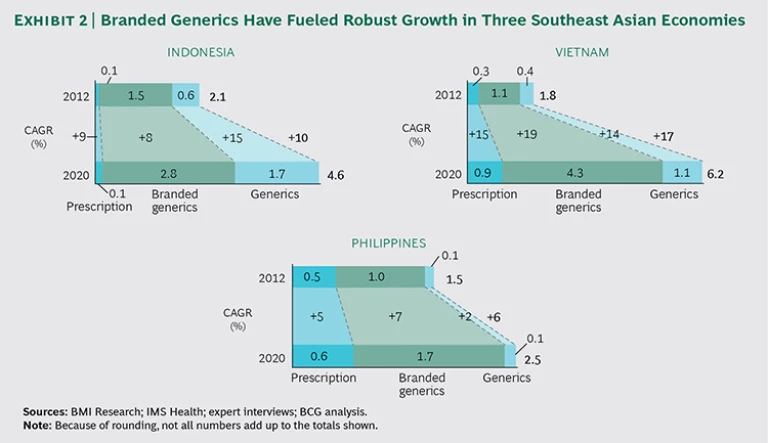

In recent years, branded generics have experienced strong growth in Southeast Asia, where they are marketed as high-quality alternatives to unbranded generics. (See Exhibit 2.) A recognizable brand and company name imply quality, the drugs are viewed as safe and effective, and the lower price is especially welcome in public hospitals, where doctors have a mandate to prescribe branded generics or conventional generics in place of patented products whenever possible.

Branded generics do not play much of a role in mature health systems, however. Most developed health care markets—in North America and Europe, for example—have stringent requirements in place to safeguard the quality of less expensive, but equally effective, generic drugs.

But this raises a question: Will branded generics become obsolete as emerging markets mature? It’s certainly possible that branded generics will gradually become less desirable if regulatory mechanisms improve the quality of pharmaceuticals in emerging markets. Much depends upon how quickly countries manage three intersecting forces: the power of physicians, hospitals, and governments to make prescription decisions; the evolution of private and public insurance; and regulatory reform.

Here’s a quick look at how various scenarios could play out:

- A country that launches a state-funded health care system will generate intense price pressure in favor of the least expensive generics, making branded generics obsolete.

- A market dominated by private insurance will favor the least expensive generics because a free-market movement will tend toward cost-effective solutions. This is especially true in cases where patients have little control over their prescriptions.

- A loose regulatory environment will give branded generics an advantage. Regions with minimal quality enforcement will continue to require them because of their high quality.

- Private insurance companies may position branded generics as part of their premium policies to capture higher market shares, thereby boosting the sales of branded generics.

Regardless of how these scenarios play out over time, a well-executed strategy for branded generics can help MNCs create value over the near and medium terms. And, perhaps more important, companies can build on their success with branded generics and seize additional growth opportunities.

A Springboard for Long-Term Opportunities

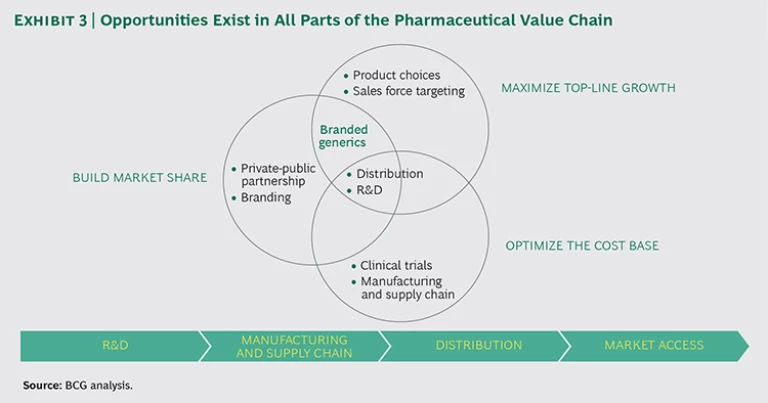

By establishing a strong foothold in Southeast Asia with branded generics, MNCs can do much more than sell pharmaceuticals—they can build a robust presence within the region’s pharmaceutical value chain. (See Exhibit 3.) Participating in the local economy helps MNCs to better understand patients’ needs; develop relationships with local physicians, hospitals, distributors, and retail pharmacies; and identify gaps within existing markets. Armed with this knowledge, MNCs can better position themselves to compete with local unbranded generics and create sustainable value for consumers.

Companies looking to expand their footprint in emerging markets will need to focus on where they can create the greatest value. This may require some fundamental shifts in those companies’ standard business models. MNCs should take the following actions to secure big wins in emerging markets such as Southeast Asia.

Develop targeted, region-specific R&D. R&D in emerging markets is rarely adapted to local needs and preferences. MNCs typically import and distribute the same types of drugs in those markets that they created for developed markets. But pharmaceutical needs and preferences in emerging markets may differ from those in the West. Emerging markets have a unique profile of infectious diseases, such as Dengue, as well as genotype-specific diseases, such as systemic lupus erythematosus.

In addition, emerging markets may need products that are suitable for local conditions, such as heat-stable medications. Pharma companies that tailor their R&D programs to address these differences will have much greater success than their counterparts that do not. By localizing R&D efforts, companies also have an opportunity to build up the region’s infrastructure and capabilities.

Establish public-private partnerships. Strategic partnerships with local authorities help MNCs gain greater access to previously underserved populations. Novartis is doing this with its Arogya Parivar program, a public-private partnership that addresses health challenges among India’s rural poor. Novartis recruits and trains residents in remote villages to become health educators to keep people informed about disease prevention and the benefits of seeking timely treatment. Local teams also work with doctors to organize mobile clinics that provide access to screening, diagnosis, and treatment. The program became profitable in 2012 and has now expanded to include Kenya, Vietnam, and Indonesia.

Differentiate from unbranded generics. MNCs need to establish superior brand images to differentiate their products from unbranded generic competitors. This can be achieved by shaping their product portfolios to address unmet needs and by focusing on innovative, difficult-to-replicate products.

For example, companies may wish to develop biosimilars, or follow-on biologics, as an alternative to original biologics whose patents have expired. Biosimilars are not generics (identical copies of already approved products). Rather, they are highly similar versions of already approved products—and there’s a rapidly growing market for these drugs in certain sectors because they are priced at a discount to the original biologics. A recent report by Datamonitor Healthcare, for example, predicts nearly 40-fold growth in sales of biosimilars for HR+/HER2– types of breast cancer from 2018 through 2024.

Because biologics are complex molecules originally derived from living organisms, they can be extremely sensitive to changes in the manufacturing process. MNCs with deep expertise in the complicated process of producing biologics will have an advantage over local generics players.

Build a strong local distribution network. To secure full market coverage, it is essential to establish local manufacturing and distribution networks. Strategic placement of manufacturing hubs and strong collaboration with local distributors—particularly those with extensive networks and existing relationships—are important for the timely delivery of high-quality drugs. Inefficient manufacturing networks can create complex supply chain issues and damage an MNC’s reputation.

Explore joint ventures. A long-term partnership with a local organization through a joint venture or acquisition can be a quick way to build manufacturing and distribution capabilities. For example, the German pharmaceutical company Fresenius Kabi bought a 51% stake in Indonesian drugmaker Ethica Industri Farmasi. This joint venture provides Fresenius with valuable manufacturing capabilities while Indonesia rolls out its universal health care program. Similarly, UK-based GlaxoSmithKline partnered with Indian manufacturer Dr. Reddy’s Laboratories, gaining exclusive access to Dr. Reddy’s manufacturing capabilities as well as its portfolio of more than 100 branded pharmaceuticals in multiple segments. Other MNCs have licensed their products in an effort to reach emerging markets. EastPharma, a drugmaker in Turkey, acquired the rights to manufacture and market eight Roche branded generics registered in Turkey.

Southeast Asia comprises complicated and diverse markets with unique sets of challenges for MNCs. But we see much to gain from entering local markets. Using branded generics as a starting point, MNCs can make significant inroads into Southeast Asia. Over time, by establishing a strong local presence and forging strategic partnerships with local organizations, MNCs can expand into these markets in ways that generate meaningful growth and provide lasting benefits to the local community.