The CEO of a large consumer goods company was near the end of his rope. He was one year into a large-scale transformation that was focused on growth through a shift into premium products. The company had invested millions of dollars to develop an innovative product that warranted higher prices. The early results had been promising: initial sales were strong. However, the transformation was wrapping up, and the CEO’s attention was being drawn to other challenges: the company had begun to revert to its old ways.

The engineering team did not seem to be on track to produce additional innovative designs. Recent prototypes were unimpressive. Discounting had crept back in, and the average price had fallen below the company’s target. One successful product would not be enough to keep the business on track. Had the company invested millions to achieve only temporary results?

This predicament is all too familiar. Virtually all industries today face a whirlwind of new technologies, evolving customer behaviors, globalization, and pressure from investors. In response, companies launch transformations—profound changes to the company strategy, business model, organization, culture, people, and processes—aimed at achieving sustainable performance improvement. (See Transformation: The Imperative to Change , BCG report, November 2014; The New CEO’s Guide to Transformation , BCG Focus, May 2015; and A Leader’s Guide to “Always-On” Transformation , BCG Focus, November 2015.)

Yet many transformations fail to deliver. Why? In many cases, companies focus too much on the finish line and not enough on capabilities, the muscles they need to build and strengthen in order to get and—most important—to stay there. By “capability,” we mean an ingrained ability to do something well in a way that improves business performance. For example, a company could launch a transformation to improve its R&D performance, develop a new digital service, or change business models from wholesale to retail. Each of these transformations requires new, specific capabilities that the company needs to build—or acquire—to execute the transformation and sustain its benefits.

BCG contends that, in fact, lasting transformations hinge on capabilities. Identifying and developing the requisite capabilities can mean the difference between a successful, sustained transformation and a short-term effort whose results quickly fade. In this report, we discuss the main reasons companies fall short in this regard, along with three imperatives for building capabilities effectively and generating lasting gains. Companies must address all aspects of the target capability by applying a comprehensive definition, follow a systematic development approach, and make sure that the leaders are engaged and have committed their support.

Where Do Companies Go Wrong?

In many organizations, the approach to capabilities falls short for several reasons. First, as in the case of the CEO described above, some leaders fail to recognize the importance of the target capabilities and, therefore, do not think about systematically incorporating them into the transformation itself.

Second, building capabilities generally requires coordination across functions and business units. For example, developing a robust digital capability might require new talent (supported by HR), new tools (IT), new processes (operations), and new governance (leadership). In many companies, it can be difficult to bring these groups together in a coordinated effort and even harder to get them to see the big picture. As a result, many companies hand the capability-building process to HR alone or seek to address it through a few days of training.

Third, acquiring the new capabilities might represent a huge leap into the unknown. A company in a process-heavy industry such as mining might find it reasonably easy to develop lean capabilities to make its production processes more efficient. But it might struggle to implement a new digital capability that requires upgrades to employee skills, technology, and other aspects of the organization.

The biggest obstacle, however, is that new capabilities call for fundamental changes in behaviors—the ways that employees, managers, and executives work on a daily basis. And behavioral change is hard. Without a systematic and explicit approach, companies can, at best, change these behaviors only superficially and temporarily. Once the transformation process is over and attention shifts to the next priority, employees can easily revert to their old ways of working, and the improvements of the transformation disappear.

A Comprehensive Definition

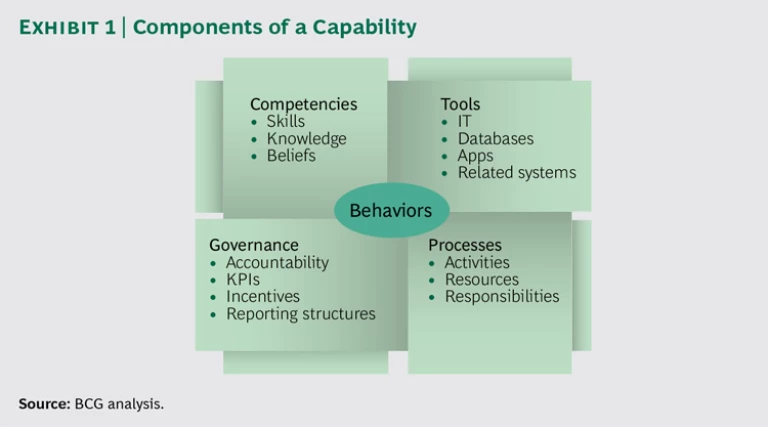

To address these challenges, companies need to start with a comprehensive definition. As stated above, a capability is a deeply ingrained ability to do something well in a way that improves business performance. At the core are behaviors: the activities, interactions, and decisions made by a set of individuals in a company who exemplify that capability.

To enable and sustain such behaviors, we define four underlying components of a capability:

- Competencies. The skills, knowledge, and beliefs held by employees.

- Tools. IT, databases, apps, and related systems.

- Processes. Activities, resources, and responsibilities that govern the way work is divided and done.

- Governance. Accountability, KPIs, incentives, and reporting structures.

Collectively, these four elements reinforce each other and lead to sustainable changes in behaviors, with the ultimate objective of helping the company create value. (See Exhibit 1.)

Consider a consumer goods company that wants to build a capability in marketing and promotion. The company could change behaviors by systematically incorporating all four elements:

- Competencies could include, for example, knowledge about which promotions are best suited to specific retail channels, the analytical skills required to build a promotion strategy, and the belief that promotion decisions should be driven by data.

- Tools could include an analytics system that collects more accurate point-of-sale data, customers’ mobile-browsing and purchasing history, and other information for generating insights for sales and marketing leaders.

- Processes could include the way the company plans for and rolls out events, how it allocates roles and resources across the team, and how field reps interact with store managers.

- Governance could include a new organizational function that reports to the CFO, new metrics to assess performance and improvement over time, and a new incentive structure for rewarding performance.

It’s important to note that these elements are not always weighted equally. Certain capabilities emphasize some elements more than others. Nevertheless, a strong capability does incorporate some piece of all four elements in order to fundamentally reshape behaviors. (See “A Technology Company Builds a New Pricing Capability.”)

A TECHNOLOGY COMPANY BUILDS A NEW PRICING CAPABILITY

Revenues and profits at a large office-product manufacturer were declining as the overall market for its products shrank. In response, the company launched a transformation to convert its business model: instead of selling products, it would sell services and solutions. As part of that transformation, the company set about improving and reshaping its pricing capability.

Prior to that point, pricing had been a cumbersome process that was linked to cost rather than to what the market would bear. Sales reps offered discounts that were based on gut instinct. And even in today’s increasingly digital environment, the company had no pricing-analytics function: little sales data made it back out to the field.

In response, the company took steps to systematically build a pricing capability that was part of its transformation journey and focused on all four components:

- Competencies. Because pricing was such a critical element of the transformation—and because the company had had no dedicated pricing team prior to that point—leaders opted first to hire outsiders who already had the required competencies. The company created a new pricing and analytics group built around these experts. They trained company employees, rigorously developing their pricing knowledge, skills, and beliefs.

- Tools. The company developed an analytical tool that assessed product features and identified those with the biggest impact on pricing. In addition, the company rolled out a dashboard of sales data, which broke pricing down by region, product line, and sales rep. With these tools, the sales force gained a clearer indication of the pricing options for specific customers, and analysts were better able to identify trends and support field reps. Management also used the tools to track performance.

- Processes. Several processes were altered, particularly those associated with discounting. Once a list price was set, sales reps had clear guidelines—and guardrails—regarding the discounts they could offer. Steeper discounts required approvals from higher levels—up to the global head of sales.

- Governance. The company created a new role: a vice president of pricing oversees the entire function and reports to the CFO. And the company refined its performance incentives for the sales force, introducing a bonus scheme that emphasizes pricing and is simple enough that a rep can easily do the necessary calculations in his or her head.

As a result of efforts associated with each of the four dimensions above, the behaviors of pricing team members have fundamentally changed. No longer do sales reps offer discounts on the basis their gut instincts. Instead, they have a standardized approach that is based on a quantitative analysis of the market. In addition, the company uses the pricing and analytics group to continually measure its performance and improve over time.

Within five months of rolling out the new capability, the company was able to raise prices by more than 2% on average, leading to approximately $50 million in new revenues—and an 8% improvement in gross margin—each year. As the transformation journey continues, the new pricing capability is helping the company ensure that these gains are sustainable.

Ten Key Practices for Systematically Building Capabilities

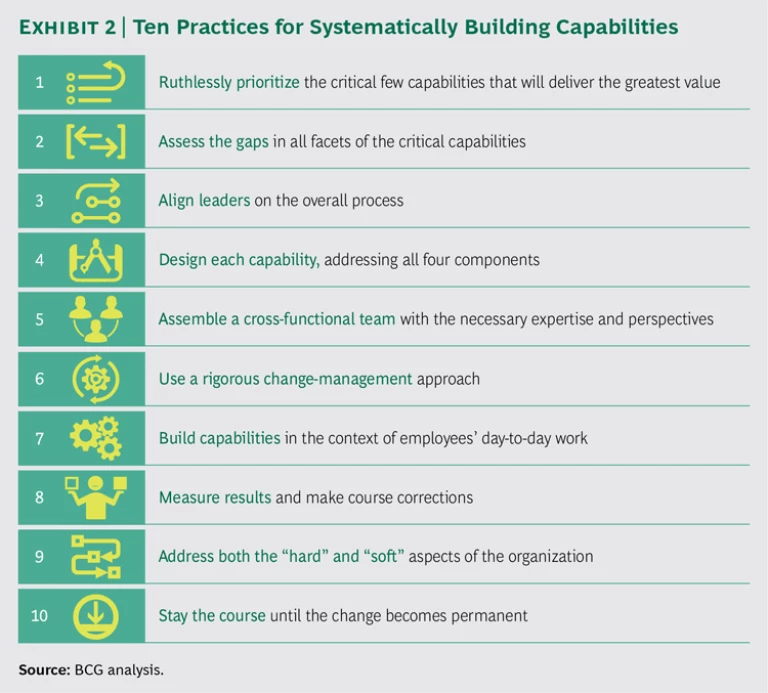

With a comprehensive definition in place, companies can turn their attention to identifying and developing the capabilities they will need to generate lasting change through transformation. On the basis of our experience, we have identified ten key practices for building capabilities. (See Exhibit 2.)

Ruthlessly prioritize the critical few capabilities that will deliver the greatest value. The first step is to determine what’s needed: the subset of capabilities that are critical for the transformation. This requires understanding the goals of the transformation and identifying the specific capabilities that will help the company achieve those aims. The company then needs to select the few capabilities that will generate the greatest value and prioritize ruthlessly. A company that tries to build too many capabilities at once can spread its resources too thin and accomplish nothing.

For example, a consumer goods company sought to expand its global presence and to use digital technology to improve its performance. In support of these strategic objectives, the company conducted internal and external interviews and a benchmarking analysis and came up with a list of critical capabilities. To prioritize them, the company ranked the capabilities according to two dimensions: the relative importance of each capability to the company’s strategy and the difficulty of implementation. Management decided that the capabilities that were important to the strategy and easy to implement would require relatively less direct oversight, which—later in the transformation—could be passed on to line managers. Conversely, capabilities that were important but hardest to implement would require a different approach. Those would require significant time, energy, resources, and commitment from leadership, so the company opted to create teams dedicated to building these as part of the transformation program.

Assess the gaps in all facets of the critical capabilities. Companies need to define the gaps between their current capabilities and their target state relative to all four components: competencies, tools, processes, and governance. Many companies err at this stage, thinking of capabilities as single-dimensional attributes rather than considering all four dimensions of each capability. The gap analysis helps organizations start to map out the effort that will be required during the transformation.

Align leaders on the overall process. Senior leaders at the company need to understand not only the target capabilities but also the full scope of the process required to develop them. Executives must be prepared to invest time and energy to see that process through. And the process can extend over a long period during which the executives will likely face demands on their time and attention in overseeing the transformation itself. Clear alignment from the beginning offers a reality check for making sure that leaders are prepared to support the initiative.

Design each capability, addressing all four components. The next step is to design each of the required capabilities, addressing all four components of the definition. For example, a company seeking to build an R&D capability requires more than just technical expertise. It also needs, for example, tools to support research, processes to allocate resources among various projects, and metrics to evaluate performance. This requires recognizing that capabilities are not addressed only through training. (See “An Auto Manufacturer Builds Digital Capabilities.”)

AN AUTO MANUFACTURER BUILDS DIGITAL CAPABILITIES

While some capabilities are unique to a specific company and transformation, others—such as digital technology—are more widespread and more complex to develop. (See “The Digital Imperative,” BCG article, March 2015.) Digital encompasses singular, tactical capabilities such as big data, analytics, and social media, yet it also may require the company to make broader changes to its business model. Moreover, in many industries, it requires an influx of new talent through direct hiring, a joint venture, or a partnership with another company. More fundamentally, building a digital capability requires a new mindset of rapid prototyping and learning through experience. (See How to Jump-Start a Digital Transformation, BCG Focus, September 2015.)

For example, the executives at a multinational automobile company recognized that it would need to incorporate digital technology more directly, both in its internal processes and in the vehicles it sold. The company launched a digital transformation, including a dedicated effort to build the components of their capabilities:

- Competencies. The company needed to develop several competencies, including rapid prototyping and analytics, to support digital capabilities. Management hired experienced outsiders and paired some of the new hires with current employees in a reverse-mentoring process that would spread competencies quickly throughout the company.

- Tools. The company upgraded its IT tools and systems across the board, making changes to more than 2,000 applications. For example, a new-product data-management tool allowed designers at multiple sites around the world to collaborate on new products and accurately track all information related to their development and release.

- Processes. Rather than using the traditional product-development approach, which is built on a linear series of steps, the company shifted to agile product development, which is faster, more iterative, and more focused on the customer experience. In an agile process, developers start by turning their ideas into a very stripped-down prototype, which they show to potential customers in order to capture their feedback. Using the agile approach, the company was able to deliver a full working version of a new product in just 13 weeks, during which there were several rounds of feedback and design changes from users. The process took far less time than would have been necessary using the old software-development approach.

- Governance. After a few early-stage tests, it became clear that the company didn’t have the right internal IT structure in place to support the digital capabilities. It therefore split its IT function in two: one section would support the company’s existing operations using traditional legacy systems, while the other would move faster to develop cloud-based mobile technology and other digital tools that could support the new initiatives.

Most important, employees, managers, and leaders all began to change their behaviors in lasting ways. For example, instead of interacting only occasionally, the IT teams made a habit of presenting the business teams with testable prototypes for feedback every two weeks. Procurement teams that had been spending three to six months recruiting vendors before offering long-term commitments started signing lower-risk trial-commitment contracts within one week.

As a result of these changes, the company was able to build digital features into its cars, giving drivers access to, for example, e-mail, voicemail, and entertainment features. It also was able to revamp its sales approach, incorporating the use of digital channels to reach out to customers at critical points in the car-buying process with highly targeted marketing messages, vehicle specifications, and other information intended to win them over. In the aggregate, the company estimated that with the incremental sales and reduced costs, the new digital capabilities would lead to approximately $150 million in profits in three years. Moreover, the company plans to continue to build on those gains. (For additional examples, see “How Five Companies Launched Digital Transformations,” BCG article, September 2015.)

Assemble a cross-functional team with the necessary expertise and perspectives. During the design process, a cross-functional team can ensure that critical aspects don’t fall through the cracks. Such teams include representatives from, for instance, HR, IT, and finance. The team does not need to be large, but it should include the right experts and stakeholders.

The consumer goods company mentioned above created a permanent corporate function that is directly responsible for identifying and developing new capabilities and designing ways to embed them in the company. This function comprised people from HR, IT, and operations, as well as other departments.

Use a rigorous change-management approach. Creating lasting behavioral change is hard and requires the same rigorous approach to implementation as the transformation itself. A clear implementation plan built on rigorous change-management principles should include detailed milestones and KPIs, and it should establish the right team to execute the plan. (See Changing Change Management: A Blueprint That Takes Hold , BCG report, December 2012.)

Build capabilities in the context of employees’ day-to-day work. During a transformation, employees are under a great deal of pressure, and a seemingly theoretical capabilities-building project is bound to raise skepticism. Rather than treating capabilities as an abstract exercise, companies need to make the capability-building experience as practical as possible, grounding it in employees’ daily work and responsibilities. The goal of any transformation is to fundamentally change the behavior of employees and managers, leading to a new, permanent way of work-ing. A capability-building program that is practical, based in the real work that employees perform daily, and executed parallel to the business agenda of the change makes employees feel supported and leads to these real changes in behavior.

Measure results and make course corrections. Success requires measuring and reviewing the impact of all changes and adjusting the course as needed. The abstract nature of capabilities makes them challenging to define and assess. As such, companies need to establish quantitative goals and milestones, communicating openly and honestly with all involved.

To ensure the success of the overall program, implementation teams must use these metrics to continually evaluate and make appropriate adjustments. (See “An Industrial Company Pilot-Tests a Capability-Building Program for Managers.”)

AN INDUSTRIAL COMPANY PILOT-TESTS A CAPABILITY-BUILDING PROGRAM FOR MANAGERS

One industrial company had a culture that was highly oriented to processes and top-down directives. Rather than engaging in discussion and dialogue with their people, unit and department leaders acted like prescriptive taskmasters, and although the company posted decent returns, it had a poor track record for innovation. The company hired a new CEO, who quickly realized that the culture was hindering the company’s ability to solve complex problems. He initiated a transformation aimed at building up capabilities among frontline managers directly overseeing line employees. The goals were to reduce reliance on top-down tasks, increase dialogue between managers and their employees, and engage in value-based management that would ensure that all managers and employees knew the potential financial impact of their decisions.

To develop these new capabilities, the organization, rejecting theoretical training programs, opted to address the work of the managers in practical and tangible ways. Managers were taught how to reframe daily conversations with their employees. The company restructured the morning meetings that line managers held with their units, allocating time for the active solicitation of employees’ opinions and ideas, rather than simply issuing orders. Managers used simple tools such as checklists, feedback mechanisms, and learning guides to help them stick with the new target behaviors. After an initial pilot test, the company made some refinements and rolled out the program on a larger scale, training 6,000 line managers across 18 countries, in three languages.

With these new management capabilities in place, employees are now far more empowered to make suggestions, and managers have a much clearer sense of how to evaluate those suggestions. The teams—well-integrated units—are adding significant value. For example, a procedure for job sites that was recently implemented throughout the company and is saving roughly $400 million annually was the recommendation of a line employee.

Address both the “hard” and “soft” aspects of the organization. Once new capabilities are in place, companies need to take active steps to ensure that those capabilities become embedded in the company’s DNA. Such steps include changes to the hard elements of the company, such as IT systems, as well as softer aspects, such as performance assessments, incentives, and the overall culture.

For example, a company that aims to have its sales force emphasize the quality of customer interactions rather than simply concentrating on upping the volume of sales calls would need to apply new metrics for evaluating customer interactions and to incorporate the new metrics into their performance-management system, including the award system. Furthermore, sales managers would have to emphasize the importance of high-quality customer interactions on an ongoing basis.

Stay the course until the change becomes permanent. There is no finish line, and the capability-building process is never over. Companies need to stay the course, reinforcing a particular initiative until the new behavior—no longer unfamiliar—becomes second nature for employees. (See “A Software Company Builds a Capability to Support a New Business Model.”)

A SOFTWARE COMPANY BUILDS A CAPABILITY TO SUPPORT A NEW BUSINESS MODEL

As customer preferences changed, a leading software and services company needed to transform its business model from on-premises licensed software to subscription-based, cloud-hosted software as a service (SaaS). That required developing several capabilities.

The company started in a few areas, analyzing customer expectations and benchmarking its performance against that of competitors to understand the biggest gaps. The most immediate priority was “customer success.” Rather than selling software systems to customers on a one-off basis, the company had to interact with customers more frequently and directly, and it needed to develop a culture focused on anticipating and addressing their needs.

To build the customer success capability, the company assembled a cross-functional team with representatives from sales, service, and engineering. The team drew heavily on external benchmarking and expert interviews. These proved critically important, given that the company was expanding into an area in which it had little institutional expertise. Humility was key as well: even in designing the capability, leaders were leaping into unfamiliar territory.

On the competency front, the company built up its analytics and data-management skills, enabling it to track customer usage accurately and to synthesize the data into insights for improving products. It also rolled out dashboards that allowed the company to anticipate problems, spotting usage patterns, predicting customers’ needs, and addressing needs rapidly.

With regard to processes, the company had to create value for its customers by building close, long-term relationships, thus improving retention rates. Finally, the company established a new role: a customer success manager serves as a single point of contact for handling all client needs. The company also altered its KPIs, focusing on adoption, retention, and customer success metrics.

To embed the capability, the company redefined its target culture to emphasize customer service with specific behavioral changes. For example, it was no longer acceptable simply to pass customer problems from one department to another. Instead, because the company now aimed to resolve problems as soon as they arose, it authorized line employees to handle problems at the lowest possible level and collaborate to solve problems across functions.

Through these measures, the company has succeeded with the new SaaS business model, reducing churn among its customers and increasing revenues from upselling and cross-selling.

Implications for Leaders

Even companies that get the first aspects—a clear definition and the ten imperatives—right can fail if they lack the right leadership. Leaders need to guide the overall process, set expectations, model the new target behaviors, and use positive reinforcement to reward progress. They also need to allocate resources among multiple priorities and take other steps to support the change. All of this requires significant time and energy during a period in which those leaders are likely to be running other aspects of the transformation, as well as the day-to-day operations of the company.

To help leaders prioritize, we provide the following guidelines:

Know what you don’t know. Capability building can be especially difficult when the target capability resides outside the leadership team’s expertise. Leaders are naturally drawn to areas they know well and to which they can quickly add value, but transformations don’t always offer that luxury. For example, the leaders of a company that lacks first-hand digital experience but needs to become better at launching new digital initiatives might need to push themselves in ways that are unsettling. For this reason, it’s critical that they understand their own limits and become creative and resilient in building capabilities. One approach is to rely on experts, perhaps hiring from companies that already have the required capabilities. Mentorship and coaching can help. And leaders should strip away the stigma and blame associated with failure, treating setbacks as opportunities for learning.

Balance medium-term capabilities with short-term business pressures. Building capabilities takes time, resources, and energy. Moreover, the process can be thrown off track by the relentless pressure for short-term results and the competition for executive bandwidth and resources. Accordingly, it’s up to the leadership to prioritize capabilities, allocate resources, monitor the overall workload of key employees, and link progress on capabilities to short-term results.

Prevent atrophy. Organizational capabilities, like healthy muscles, atrophy if they are not tested, used, maintained, and improved. As we noted above, leaders must deal with a steady stream of new initiatives and priorities that can pull the company in new directions. To avoid losing ground, leaders must deliver strong, consistent messages about the importance of core capabilities, linking them to employee objectives and rewards and regularly evaluating capabilities against continually changing strategic requirements. Finally, leaders must foster a mindset that treats capability building as an ongoing requirement rather than a one-time event.

Make the organization more agile. Perhaps the biggest challenge for leaders, beyond developing individual capabilities, is anticipating the need to transform the company repeatedly over time. Even a theoretically perfect set of capabilities today will have to be revamped in the near future, so company leaders need to make their organization more agile, capable of thriving amid continual change.

The CEO we described in the introduction eventually realized that focusing on the outcomes of the transformation wasn’t enough. Members of the pricing team didn’t simply need new products. They needed stronger pricing capabilities, including tools. Similarly, the R&D team needed new processes that were less cumbersome and more tightly linked to manufacturing. Broader scopes of responsibility would allow engineers to better integrate perspectives from developers, designers, marketers, and customers. In sum, by doubling down on the capabilities needed to execute the transformation, the company was able to grow through stronger sales in the premium segment and to generate sustainable gains.

Many companies that launch transformations focus doggedly on demonstrating outcomes. That approach is understandable, but because it doesn’t address the underlying capabilities needed to achieve and sustain the outcomes, it’s shortsighted and will likely fail. Regardless of industry or type of transformation, capabilities are critical elements in improving performance and sustaining results, ultimately in the form of increased value creation. By focusing on the three elements discussed here—a clear and robust definition of capabilities, a structured approach for building those capabilities, and the right support from leaders—companies can successfully transform themselves to meet whatever challenges they might face.