This article is an excerpt from Creating Value Through Active Portfolio Management: The 2016 Value Creators Report (BCG report, October 2016).

2016 Value Creators Report

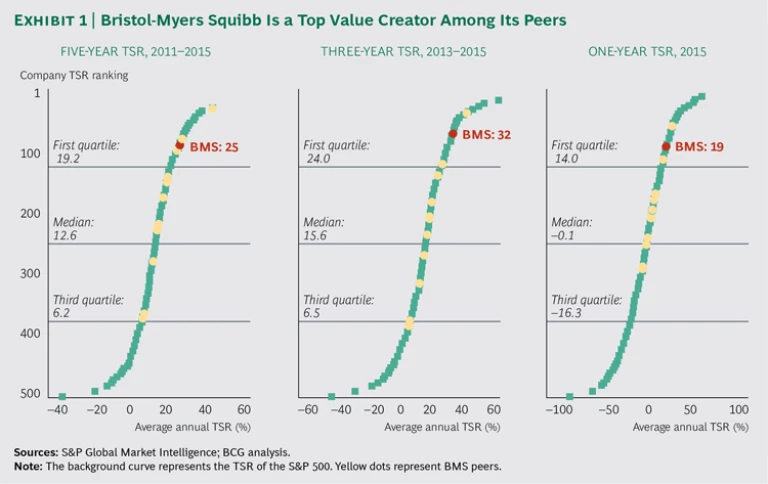

With a market capitalization in the neighborhood of $100 billion, Bristol-Myers Squibb (BMS) is one of the largest companies in the biopharma sector. It is also one of the strongest value creators. The company was number 27 in our ranking of TSR of the world’s 200 largest companies. Compared with its biopharma peers, BMS’s performance is even more impressive. From 2011 through 2015, the period covered by this year’s Value Creators study, the company was the third-best value creator in its peer group; it was the second best for the past three years and the past year. (See Exhibit 1.)

Understanding BMS’s excellent recent performance, however, requires a broader time frame: the decade-long story of how the company’s senior management transformed BMS from a diversified health care company into a biopharma pure play by systematically reshaping the company’s business and R&D portfolios.

Biopharma’s Value Crisis

Given the success of the biopharma sector during the past five years, it’s easy to forget that not too long ago, biopharma companies were exhibiting worrisome signs of secular decline. Traditionally, valuations in the sector have been driven by the success of so-called blockbuster drugs—medicines generating annual global sales of $1 billion or more. In the 1990s and early years of this century, major pharmaceutical companies relied heavily on the blockbuster model to generate sales. In 2005, blockbuster drugs accounted for about 60% of the $245 billion in sales of the ten leading pharmaceutical companies.

By the middle of the first decade of this century, however, many industry observers were worried that the blockbuster era was coming to an end. R&D productivity—the capacity to translate scientific advances into business value—was declining. Various factors were to blame, such as lengthening cycle times, rising regulatory hurdles, new barriers to access and reimbursement, tougher competition, and shorter exclusivity periods in developed markets. From 1998 to 2010, R&D productivity (as measured by the number of new molecular entities approved by the FDA per billion dollars invested) declined by approximately 40%.

At the same time, many of the industry’s earlier blockbuster drugs were starting to go off patent. And because the vast majority were so-called small molecule drugs (in which the active ingredient is based on chemical synthesis), they were relatively easy to copy and thus vulnerable to competition from low-cost generics. With R&D unable to replenish pipelines because of lower productivity, the industry faced a much discussed “patent cliff,” which threatened company valuations.

From 2000 through 2010, the market value of the top 20 pharmaceutical companies decreased by more than 30%—a paper loss of $720 billion. Interestingly, this decline was not the result of a decrease in net income. During this period, declines in volume were offset by major cost cutting and price increases, causing the net income of these companies to grow by 140%. Rather, the fall in valuations was due to the dramatic drop in industry price-to-earnings multiples—a sign that investors were scaling back their expectations.

Most large pharmaceutical companies were suffering from these trends, but BMS was hit especially hard. At best only an average performer during the blockbuster era, in 2006 the company saw its pharmaceutical business (which represented 77% of its net sales of $18 billion) suffer a one-two knockout punch. BMS lost patent exclusivity for Pravachol, a statin used to fight cholesterol, causing sales to drop by $1.2 billion from 2005 to 2006. What’s more, a patent dispute with generics maker Apotex over Plavix, one of BMS’s bestsellers, triggered a 15% decline in sales for that drug, resulting in an additional loss of $1.5 billion. BMS’s failed attempt to settle the dispute eventually led to the resignation of the company’s CEO. In September 2006, board member Jim Cornelius, the former CEO of medical technology company Guidant, was appointed interim CEO.

Refocusing the Portfolio: The “Biopharma Transformation”

In addition to resolving the company’s short-term problems, Cornelius needed to develop a strategy for coping with long-term threats—in particular, the impending end of patent exclusivity for Plavix and of the comarketing agreement for the company’s other bestseller, Abilify. At the time, many biopharma companies were turning to megamergers and portfolio diversification to protect themselves from the industry’s value crisis. But Cornelius determined that BMS was not diversified enough to have a truly balanced portfolio, nor did it have a strong enough balance sheet to fund the acquisition of entire new businesses. So, Cornelius and his senior team decided to go in precisely the opposite direction. BMS made the bold bet to become a pure-play biopharma company.

What the company termed the “biopharma transformation” had three main components:

- Divesting the company’s nonpharma assets—specifically, a nutritionals business and a wound-care and a diagnostic-imaging business that together represented nearly 25% of net sales

- Focusing the company’s strong R&D organization on developing transformational medicines in areas of unmet patient need that could serve as reliable engines of growth

- Accelerating the transition by assembling a “string of pearls”: externally developed assets that fit the new strategy and would benefit from BMS’s R&D and commercialization capabilities

The goal was to combine in one company the development and commercialization strengths of big pharma with the agility and innovative approaches to drug discovery (focused on biologics, or “large molecule” drugs) emerging from the biotech sector.

Earning the Right to Grow

Before BMS could execute its new strategy, however, it had to demonstrate that it could deliver results to shareholders while freeing up funds for new investments. In 2007, the company announced a productivity improvement initiative that over the next five years took some $2.5 billion out of the business—with the majority of the savings coming from cuts in SG&A expenses. This major improvement in cost structure not only helped fund the new strategy but also made possible modest annual increases in the company’s dividend, which signaled to investors the company’s growing financial strength and put a floor under its valuation multiple.

In parallel, the company began shedding businesses that were not part of the new focus on biopharma. BMS closed its imaging business in 2007, sold its wound care business to a private equity company in 2008, and spun off its nutritionals business in an IPO in 2009. These divestitures not only freed up additional funds for investment in the most promising new therapeutic areas; they also allowed the senior executive team to focus their time and attention on assembling a new biopharma portfolio.

One area the company decided to target was immuno-oncology (I-O), an innovative approach that fights cancer by harnessing the body’s immune system. Because I-O therapies, in effect, train the immune system to recognize and fight any growth in cancer cells, even after remission, they have the potential to provide long-term, high-quality survival to patients suffering from types of cancer for which the prognosis has been very poor. Moreover, the scientific mechanisms underlying I-O drugs are broadly applicable to multiple types of cancer, meaning that a single drug, used either individually or in combination with others, could have a huge market and be easier to protect from competition than traditional drugs.

Since 2004, BMS had been collaborating with Medarex, a biopharma company founded by immunologists from Dartmouth’s medical school that was using transgenic mice with a humanized immune system as a testing platform for the development of I-O drugs. Despite a failed Phase II clinical trial, BMS scientists saw enough promise in the results to become convinced that Medarex’s assets had serious potential. In 2009, BMS spent $2.4 billion to acquire the company and brought its capabilities in-house. Two drugs developed at Medarex and acquired by BMS—Yervoy and Opdivo—were among the first I-O drugs approved by the FDA (in 2011 and 2014, respectively) for use in treating certain cancers. The acquisition was the start of a major bet on immuno-oncology. In the past ten years, BMS has invested $8.3 billion in the space.

Transforming the Organization: From Originator to Science Hub

BMS has done far more, however, than simply acquire new assets. In addition to transforming its business portfolio, BMS has transformed its organization in order to manage that portfolio for value.

Although changes have taken place across the organization, some of the most important have occurred in the company’s R&D organization. In particular, R&D had to see itself not primarily as the originator of new drugs but as a science hub, responsible for making smart tradeoffs across the portfolio of potential drugs in the company’s R&D pipeline.

Building a Team of Expert Leaders. The first step was to build the right team of senior R&D leaders both to assemble the company’s new assets and to nurture their development. At many biopharma companies, senior R&D managers are too far from actual drug development work to be able to function effectively as leaders. BMS, under the leadership of then R&D head Elliott Sigal and his successor, Francis Cuss, developed a cadre of what Sigal termed “expert leaders,” hands-on R&D managers who combined a deep understanding of the science in the new therapeutic areas the company was focusing on with an ability to generalize from that understanding in order to create business value.

Revamping the Governance Model. The next step was to make a commitment to effective management of the company’s R&D pipeline. At any given moment, an R&D pipeline consists of drug candidates at different stages of development, so it requires a regular series of decisions about initiating new development projects or advancing or terminating existing ones. The quality of these decisions is absolutely critical to R&D productivity and to the overall success of the drug portfolio. Yet at many pharma companies, the process for making these decisions is ineffective, slow, bureaucratic, and sometimes highly political.

To address this concern, BMS has, over time, completely revamped its governance model—in particular, the all-important leadership committees that make decisions about initiation, progression, and termination. The new process emphasizes constructive engagement on the part of senior R&D leaders, the surfacing of tough issues, fast decision making, and a focus on serving the interests of the entire portfolio, not just individual drug candidates. The approach has allowed BMS to better compare assets across the portfolio, resolve competing interests, and allocate resources more effectively. It has also helped BMS continually prune its portfolio in order to focus capital on the most promising areas. As the full scale of the immuno-oncology opportunity has become apparent, the company has exited some of its more traditional therapeutic areas. For example, it sold its global diabetes business to AstraZeneca in 2014.

Following the Science. The company has also made changes in the ways that drug development teams are managed and rewarded. In biopharma R&D, it’s only natural for a team to want its candidate to succeed. As a result, teams tend to engage in what is known as progression-seeking behavior—championing their candidate through the steps of the development process. Progression seeking is a rational response to traditional incentives in the industry: raises, job security, and prestige in biopharma have typically been associated with the progression of a drug. But it can come at a high cost: teams sometimes aggressively champion their candidate even when progression may not be justified for scientific, strategic, or financial reasons.

To address this issue, BMS has created mechanisms to encourage project teams to “follow the science,” even when it might mean the termination of their projects. By rewarding truth seeking—following the science wherever it leads—over progression seeking, BMS ensures that R&D personnel have incentives to make the tough business decisions that maximize the value of the entire portfolio.

Leveraging External Innovation. The more R&D managers became expert leaders who followed the science, the more BMS was in a position to start taking advantage of scientific developments outside the company. By seeking external partners through a strategy that reinforced the company’s overall R&D strategic direction, the company has been able to leverage the most promising new approaches to drug development, many of which are found in university research labs and startups.

To emphasize the new focus on external innovation, the company beefed up its business development capabilities. It also “underfunded” its internal drug discovery effort to compel R&D leaders to pursue a combination of internally and externally discovered assets in order to meet their goals. Constraints on funding pushed scientists to routinely consider external partnerships as potentially better, faster, or cheaper routes to assembling the capabilities necessary to develop and test new drugs and bring them to market.

In addition to traditional acquisitions or in-licensing deals, BMS has created a vast array of partnerships with other companies to leverage their technologies for drug discovery against BMS targets or to develop companion diagnostics to the BMS drug portfolio. The company has also set up collaborative alliances for codiscovery in order to pool resources and expertise and leverage academic expertise and talent. It has even partnered with competitors to develop combination treatments.

Encouraging Cross-Functional Cooperation. Finally, BMS has recently created organizational mechanisms to increase cooperation across R&D functions and drug development teams. With the rapid advances in medical science, biopharma R&D has become increasingly specialized, resulting in the proliferation of new organizational units and the continued dominance of the functions over new-drug project teams. Because the functions frequently have more power than the project teams, they often push for decisions that optimize their own interests rather than doing what is best for the particular asset or the portfolio as a whole.

To shift the balance, BMS has reduced the functions’ control of personnel, budget, and other key decisions, giving relatively more power to project leaders responsible for determining the future development of a given drug candidate. “Focus on the asset” has become the mantra for cross-functional cooperation.

On the Edge of Breakout Growth

The moves BMS has made to reshape its portfolio and transform the organization in order to manage the portfolio for value have put the company on the edge of breakout growth.

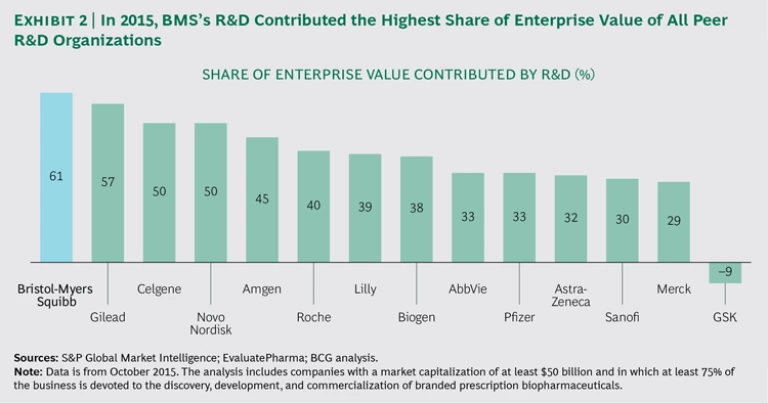

BMS’s current R&D productivity is among the highest in the industry. In 2015, the company’s late-stage pipeline and total R&D expenditure were responsible for a larger share of enterprise value than those of any other large biopharma company. (See Exhibit 2.)

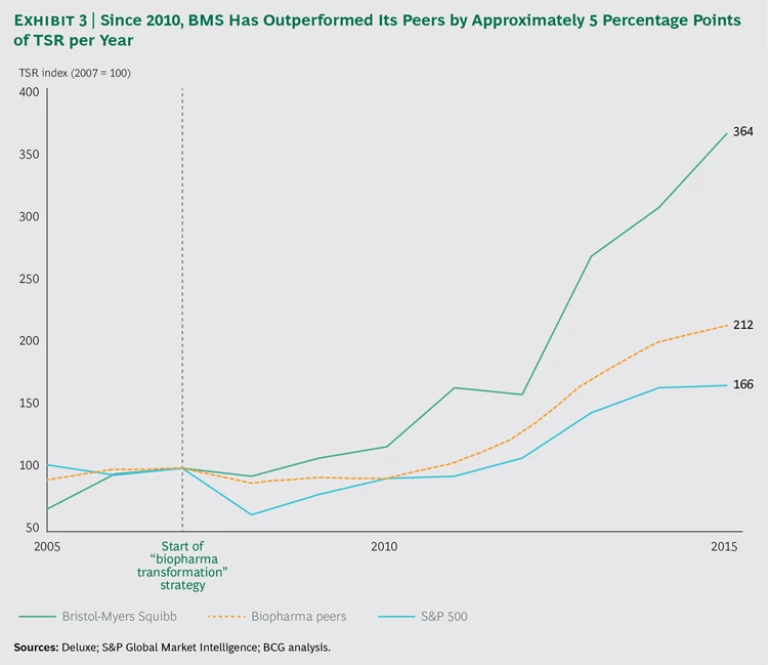

BMS has also been a first mover in the commercialization of immuno-oncology drugs precisely as I-O has emerged as the next wave of innovation in oncology drug development. Current estimates put the overall market opportunity in I-O at more than $30 billion. Since 2011, the company’s I-O business has grown from 0% to 15% of total sales, and it is expected to quadruple, to more than 50%, by 2021. Opdivo alone generated nearly $1 billion in sales in 2015, becoming a new-generation blockbuster that has helped the company outperform the industry in revenue growth for the first time since 2008. According to consensus estimates, Opdivo is expected to generate between $8 billion and $9 billion in sales by 2020, revising investors’ expectations for BMS’s share price and boosting the company’s valuation multiple. As a result, over the past six years, the company’s TSR has outpaced that of its peers by an average of 5 percentage points per year. (See Exhibit 3.)

Of course, BMS still faces major challenges. Other big-pharma companies are adopting versions of the company’s focused strategy. And there is growing competitive intensity in the I-O space, as other players look to capture the opportunity. Perhaps most important, now that investors have bid up BMS’s stock in anticipation of rapid revenue growth from the company’s new blockbusters, BMS will have to deliver on those expectations and find new ways to beat them—by rapidly increasing revenue and introducing additional new drugs. All this in a field—drug development—that is inherently risky: the announcement of a failed clinical trial in which Opdivo was tested as an initial treatment for lung cancer caused BMS’s share price to drop 16% on a single day in August 2016. But BMS isn’t standing still. It continues to follow the science, testing Opdivo and Yervoy in combination with other therapies for a wide range of cancers. And in September 2016, the company announced a major initiative to further transform how it does business. The goal: to drive growth from Opdivo and other leading drugs in the portfolio and to develop the company’s pipeline of next-generation oncology and specialty medicines for the next wave of growth.