As autonomous vehicles continue to capture the headlines, another revolution is quietly unfolding away from the highways: the digital transformation of offerings in off-road machinery and equipment.

From agriculture to construction and from mining to industrial engines, digital technology is reshaping the industrial landscape. It’s transforming an experience centered on very few interaction points between manufacturer and customer into an ongoing relationship. And this relationship is one in which automation, connectivity, and data enable customers to work more productively and more safely, continually gathering insights on their operations to improve performance and add additional services.

Digital’s promise stems from the value it adds to this relationship for both customer and manufacturer. OEMs, too, gain efficiencies and insights—insights that can help improve products and services, spawn new ones, and create new revenue opportunities.

Change is swift. Over the past year alone, hundreds of new products and services have been announced throughout the off-highway marketplace. Digital offerings run the gamut: from autonomous machinery and telematics to drones that guide autonomous bulldozers in excavating; from fleet management and predictive maintenance to diagnostics that enable quality and safety checks remotely via mobile phone. Big data and analytics inform everything from gene sequencing in agricultural production to building information management in construction and engineering.

All of these changes trigger important questions for off-highway OEMs. How should they adapt their business models and strategies to these new, rapidly evolving offerings? How do they use their strengths to capitalize on opportunities beyond the confines of their traditional sectors? How should they think about adapting their offerings to the needs of customers throughout the equipment life cycle in order to generate ever-greater mutual value?

New Competitors, New Capabilities

Digital opened the door to a new set of competitors in the auto market, and it is doing the same in each of the sectors that make up the off-highway arena. And in the process, it is blurring the dividing lines even more than machinery hardware ever did. Many of the same technologies and capabilities applicable to agricultural machinery are fungible in construction, engineering, and the industrial-engine marketplace.

Digital opened the door to a new set of competitors in the auto market and is doing the same in each of the sectors that make up the off-highway arena.

Consider the three fundamental ways that digital technologies and capabilities add value:

- Digital technologies help users create a more precise work plan. Because they can input more data (such as geographic information, soil mineral content, and temperature readings), users can start out with better, more precise work plans. A mining outfit can develop a plan for optimizing the use of one work site’s truck, for example, or a construction company can craft a more detailed plan for grading a site.

- Sensors and online connection enable users to adapt their plans continually. As conditions change, a mining operator can adjust the excavator’s levels in sections of a mine whose output is less than forecast. Or a farmer can increase the pesticide level in sections of a field where a pest infestation is greater than expected.

- Algorithms based on new data can help optimize future performance. With artificial intelligence or machine learning, the data gathered by equipment can be used to develop algorithms that enable real-time adjustments to, and better projections for, the work plan (such as changes in output levels or adjustments to equipment maintenance patterns).

These capabilities not only facilitate greater precision in planning but also enable real-time adjustments that lead to ever-improving efficiencies and performance.

Leaders, Followers, and Laggards

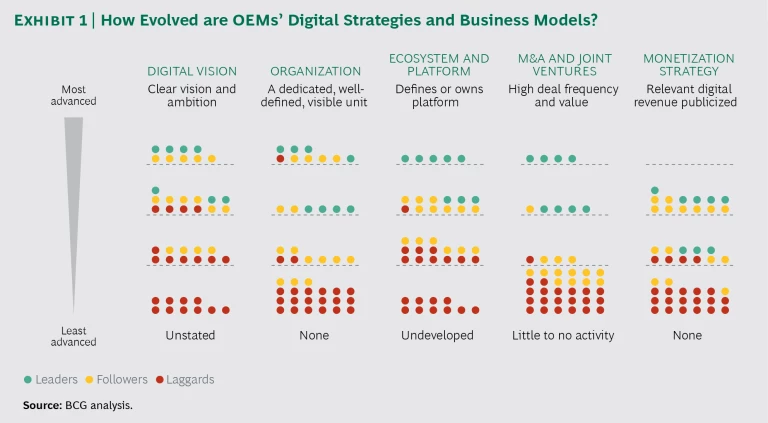

Just how evolved are the OEMs and their new competitors? We studied more than 20 OEMs, a group that accounts for more than half the sales in their respective industry markets. For each one we looked at its fundamentals, digital strategy, and business model and then classified it as a digital leader, follower, or laggard based on five criteria: digital vision; organization (essentially, whether it has a dedicated unit or team in place); ecosystem and platform approach (whether it owns or defines the platform); M&A and joint venture activities; and strategy for monetizing its digital capabilities. (See Exhibit 1.)

In each industry, we identified two or three digital leaders, many of them also quality leaders or industry icons. These companies have two things in common: an ambitious (and credible) publicly articulated digital vision and a visible organization dedicated to the effort. This means having a working unit that is funded, that has a high-level leader, and that is independent enough to innovate while remaining closely connected to the company (as opposed to being a segregated unit working in obscurity).

- Digital Leaders. Although the marketplace for digital offerings is still at an early stage, the leaders have begun developing platforms—largely open source, in order to share risk and attract ideas from beyond OEMs’ traditional expertise. Few digital leaders are very active in M&A or joint ventures. At this point, it is difficult to quantify the potential financial impact (actual or targeted) of their digital joint ventures. And in terms of monetization, even those in the vanguard are still only in experimentation mode. Today, entry-level offerings are mostly free or presented as subscription-based upgrades with limited standalone revenue streams.

- Digital Followers. These companies are pursuing digital offerings (some of them via partnerships), but not in a holistic way. Their progress—as measured by their vision, organization, and other criteria—is spotty.

- Digital Laggards. These companies are a mixed bag. Many are emerging-market OEMs, which have been rapidly closing the gap in mechanics, technology, and quality through acquisitions, strategic partnerships, and R&D investment. Digital could well be a much-needed catalyst of competitive advantage for developed-market OEMs that have forfeited market share to these emerging-market companies.

Digital Offerings Transform Service and Relationships

Digital doesn’t just entail thinking about strategy or new markets. It means fundamentally revisiting the customer value proposition and envisioning new business models and offerings that go well beyond the sale of equipment and parts. Ultimately, it enables manufacturers to provide a whole spectrum of service-based offerings that help customers derive maximum benefit and enhanced value throughout the life of their equipment.

We systematically assessed the digital products currently offered by the OEMs in our study pool—some 200 products in all. In addition, we analyzed the products of about 20 new entrants from outside the given industries. BCG industry and functional-area experts (in such areas as strategy, operations, big data and analytics, lean manufacturing, and product innovation) added their insights to our findings.

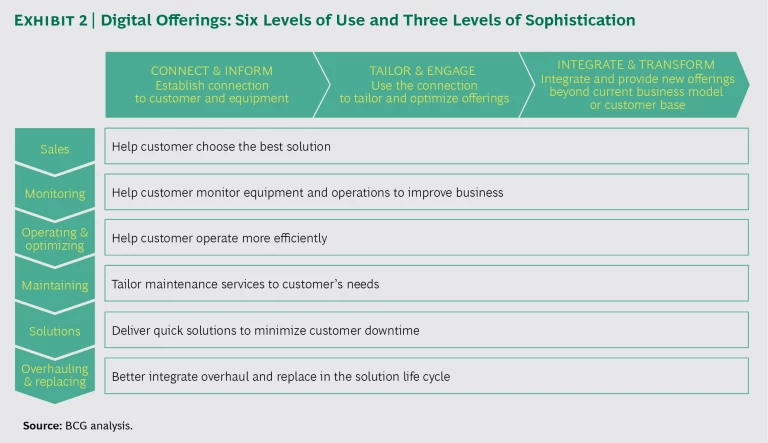

We examined the OEMs’ digital offerings along two dimensions: the ways in which customers use their equipment throughout its life cycle and the degree of sophistication of their digital offerings. (See Exhibit 2.)

First, let’s consider the spectrum of functions that OEMs offer customers:

- Sales: providing the customer with a product or service, as well as marketplace information, information and support in the purchase of spare parts, and access to equipment rental services

- Monitoring: everything from providing simple telemetric data to fleet monitoring and ultimately, data services; an advanced example in agriculture would be offering benchmarking data to farmers or yield information and forecasts to commodity and financial investment firms

- Operating and Optimizing: from simply representing operational data to providing real-time information on fleet operations; an example in construction or mining would be autonomous operations

- Maintaining: from providing static service schedules and technical documentation to offering preventive- and condition-based maintenance

- Solutions: building in features associated with avoiding or minimizing equipment downtime, from simple alarm notifications to repair advice aided by augmented reality and remote diagnostics

- Overhauling and Replacing: providing information and guidance informed by equipment status, service history data, and fleet data, which together facilitate a tailored solution for the customer; this level of offering can even consist of selling used or reconditioned equipment in situations where such sales don’t appear promising

The most sophisticated offerings available today combine elements of monitoring, operating and optimizing, and maintaining into packages that essentially provide the customer with an operating system. In agriculture, for example, these would include recommendations on inputs, crop yield analysis, and various aspects of farm management—such as optimizing machine time and improving fleet management (through machine-to-machine communication). Universal operating systems that allow decoupling from hardware are just beginning to emerge; consider, for example, ISOBUS, the well-established protocol for electronic communication among implements, tractors, and computers.

The most sophisticated offerings available today essentially provide the customer with an operating system.

Across each of these use cases, digital offerings fall within one of three increasingly sophisticated levels, each providing a foundation for the next level.

Connect and Inform. The most basic level involves establishing a digital connection for the customer and the equipment through connectivity hardware and a first digital stack—data management and foundational applications that aid adoption. The information and insights that emerge from this connection allow the customer to take appropriate action. Connect-and-inform offerings enable customers to achieve basic efficiencies, such as knowing where their equipment is and who is operating it. At this stage, OEMs are able to target sales and operational activities; for instance, they can proactively offer information about spare parts and overnight delivery options so that if a breakdown occurs, the customer can avoid or minimize downtime.

Tailor and Engage. Here, OEMs proactively change and modify products and services through the customer connection, tailoring them depending on usage patterns and the condition of the customer’s equipment. They can offer analytics and even data scientists to help customers interpret their data.

Beyond achieving efficiencies, OEMs operating at this level can enhance revenues in their service business through proactive service offerings and parts sales. For example, an OEM can check on the status of the equipment and let the customer know that it could soon break down—and point the customer to the nearest dealer. Or the OEM can send the customer a warning about equipment wear, along with an option to order a spare part. If the customer uses the task-scheduling feature, the OEM can even propose a time slot when the equipment is idle, thus minimizing downtime. For customers for whom any downtime during peak usage periods can be catastrophic—such as farmers during harvest time—such an offering could mean the difference between profit and loss. Because parts represent a large portion of OEM revenues, the ability to keep tabs on customers’ equipment delivers big efficiencies in sales, while providing customers with tremendous value by keeping their operations moving.

Integrate and Transform. At the most advanced level, the OEM goes beyond selling hardware and services to selling availability and performance—in other words, equipment (and maintenance) as a service. For example, instead of selling a construction company a bulldozer, the OEM might sell it a comprehensive package featuring X kilometers of grading per year, plus routine maintenance including parts and labor, for a period of X years with a guaranteed uptime.

This level entails broadening the business model to pursue new revenue by monetizing data. Along the way, the customer’s business model may be transformed. For example, aggregated data from the engine software of a marine customer could reveal the number of customer ships sitting idle in a specific port—a trade volume metric valuable to economists and analysts. Or an OEM, aware of the average utilization rate of its excavators in, say, China, could offer to interested parties a sound indicator of building activity (and an essential component of GDP) in a region known for its lack of reliable data.

The OEM of the Future

To illustrate the life cycle of services spanning these three sophistication levels, consider a hypothetical construction equipment maker that embodies best practice. The company embeds a telematics control unit as a standard feature in all of its latest bulldozers and excavators. This allows the customer to view machine, operational, and location data directly on the machine as well as on a remote device. The company soon adds to the unit a spare-parts catalogue and web shop that lets customers buy parts directly from the field (connect and inform).

Next (tailor and engage), the OEM uses the data collected to introduce condition monitoring and preventive maintenance. This service informs customers about critical machine conditions and proactively contacts them for service—service offered at a discount through the OEM’s dealers to customers who signed up. Preventive maintenance expands the share of services carried out through the OEM’s network of dealers and service centers. The OEM integrates its web shop into this service; once a problem is identified, customers can go online and be directed to the parts and repairs they need to solve their particular problem.

Drawing on the detailed operational insights gained in the previous stage, the OEM introduces a new offering: condition-based maintenance paired with an uptime guarantee sold together with its machines for a monthly fee. The OEM has partnered with parts suppliers to turn its original parts-buying site into a shop featuring a full range of supplies for a work site, from consumables (such as oil, lubricants, and coolants) to tools and gear (such as work gloves and hearing protectors).

Moving beyond its traditional business model (integrate and transform), the OEM contracts with three major road construction companies to sell its equipment as a service—selling a set number of operating hours, including all necessary service and repairs.

Finally, the OEM makes an innovative push into new competitive territory: a joint venture with a customer, a highway construction firm that achieved major productivity gains and reductions in total cost of ownership thanks to the OEM’s cutting-edge autonomous operations technologies. Ultimately, as the joint venture’s business grows, the partners decide to spin it off.

Five Imperatives

Whether leader, follower, or laggard, any OEM competing in the off-highway digital arena needs to focus on five imperatives.

Envision contrasting future scenarios for the industry. Inform your strategy, monitor developments, and adapt accordingly. For example, over the next 20 years, what might your North American agriculture customers look like? With large swaths of farmland owned by corporations, will contract farmers predominate—and will they be buying your equipment? Or will the megacompanies handle operations, tapping the most advanced technologies and driving out contractors? For traditional OEMs in particular, looking at various scenarios across off-highway sectors will help spur thinking about where opportunities overlap.

For traditional OEMs in particular, looking at various scenarios across off-highway sectors will help spur thinking about where opportunities overlap.

Identify and foster ecosystems and partnerships. Reach out to customers, tech providers, and companies in adjacent fields to complement your own offerings, expertise, and capabilities. OEMs will almost certainly need a diverse set of capabilities far beyond their current off-highway offerings. Partnering is in most cases probably the only economically feasible way to acquire these new capabilities.

Operationalize your digital strategy. Commit resources to the must-have offerings and capabilities—those that establish a link with customers and their equipment. Here, OEMs have the advantage over technology companies: they control the hardware, the connection to the customer, and the customer relationship. Move toward more service- and solution-oriented offerings, such as business process consulting and network optimization, and critical technologies, such as autonomous equipment. Offerings could also be as straightforward as providing location information to clients for free, which can lower their insurance premiums.

Experiment with product strategy and digital strategy. Extend conventional monitor-and-maintain offerings with, for example, web shops for spare parts or new remote-monitoring apps. In technical platforms, pursue cutting-edge offerings, such as intelligent robots added to the automated- and autonomous-operations offerings. At the same time, consider retrofitting older equipment so it can take advantage of the digital capabilities embedded in newer equipment. Given the investment cost and life span of heavy machinery, it will be years before a customer’s fleet is fully digitized. Retrofitting (even at your own cost) may be the only way to ensure that you get the data you need to build and maintain digital offerings.

Learn and adapt. Innovation—in technologies, processes, and business models—is happening at a breakneck pace. The further out on the sophistication spectrum, the more disruptive digital can be. New entrants can disrupt the most, as they have in other B2B sectors. Set your organization up for continuous learning and the ability and will to adapt. That is the key to surviving—and thriving.

Digital holds great promise for off-highway OEMs, but the marketplace is still in its early stages and much is uncertain. Companies that take a wait-and-see approach risk getting locked out of the competition later. At the same time, betting on a specific direction now can be equally risky. OEMs that envision different future scenarios for key industries, foster ecosystems and partnerships, implement a baseline digital strategy, experiment with their digital and product strategies, and foster continuous learning and adapting can stay engaged and flexible—and be poised for action and advantage.