For the US grocery industry, tectonic changes are underway.

Recent developments underscore how pivotal a moment this is: News that Amazon was acquiring Whole Foods sent shock waves through the market (shares of the country’s largest mass and food retailers tumbled the day of the announcement). Brick-and-mortar chains have been aggressively cutting prices. Walmart’s e-commerce acquisitions—first of the shopping site Jet and then of menswear company Bonobos—demonstrate the company’s desire to keep pace as online retail takes off. All this on top of pressure from retail newcomers (such as European discounters Aldi and Lidl) and small brands that are fueling industry growth and taking share from established players.

Yet amid disruption and dislocation in the retail landscape, most leading consumer packaged goods (CPG) manufacturers appear stuck, uncertain about where to stake their bets and how to proceed. Although retailers’ business models are still evolving, we believe a winning model is already emerging. Waiting on the sidelines is risky. It’s time for every CPG company to pursue an e-commerce strategy suited to its product portfolio, determine the supply chain challenges, and take steps to prime its supply chain for digital.

The Tipping Point Is Near

Although online grocery sales in the US are still only a modest percentage of total sales, over the next two years, according to BCG projections, half of the growth in grocery sales in North America will come from e-commerce channels. (See Digital Insurgents, Emerging Models, and the Disruption of CPG and Retail , BCG Focus, May 2017.) Indeed, for the CPG companies that participated in the 2017 Supply Chain Benchmarking Study, conducted by BCG and the Grocery Manufacturers Association (GMA), the median growth rate for online sales since 2015 was 40%, compared with 3% for brick-and-mortar sales. Further, BCG research has shown that regardless of sector, once online sales reach 5% of an industry’s total sales, growth accelerates rapidly to 10% and beyond. This tipping point is fast approaching for the US grocery industry.

Once online sales reach 5% of an industry’s total sales, growth accelerates rapidly to 10% and beyond.

E-commerce complicates CPG companies’ economics. It also has significant supply chain implications—on SKU proliferation, packaging, inventory forecasting, and service expectations, in particular. Leading-edge CPG companies recognize these challenges and are tackling them head on in a holistic way. These digital trailblazers—33% of responding CPG companies—are forging ahead with multiple e-commerce initiatives, investing in e-commerce talent and technologies and building operational capabilities. Most of the rest, however, are taking a wait-and-see stance, investing only in basic capabilities and avoiding significant bets.

Key Challenges, Model by Model

In grocery, several different business models can support e-commerce. The three most common are click and collect, in which traditional grocers let consumers order online and then pick up their purchases at the store; pure play, in which retailers offer only online sales; and direct to consumer (DTC), which cuts out the retailer altogether. Each model is best for different product types, and each introduces new supply chain challenges.

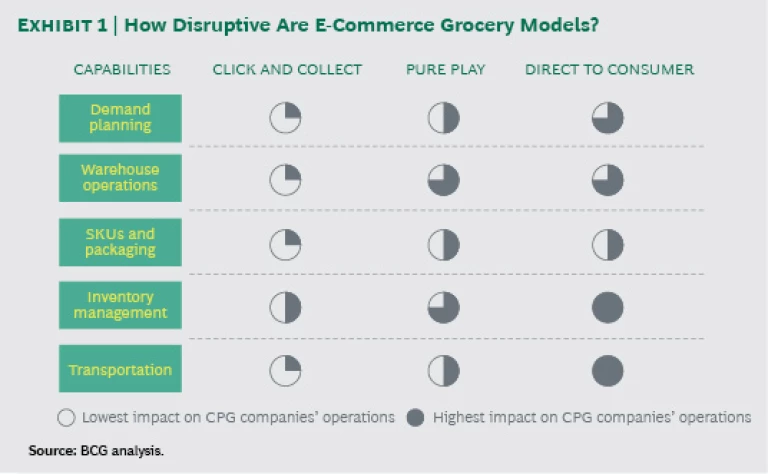

Click and collect is least disruptive to CPG manufacturers’ existing operations. The pure-play providers’ model varies on the basis of price, convenience, or specific product categories. DTC is the most disruptive. Let’s consider each model and its implications. (See Exhibit 1.)

Click and Collect. In our view, click and collect—already used by Walmart, Target, and grocery-only chains such as Kroger—will likely be the dominant model in the US grocery industry (except in the densest urban areas, where the economics of direct delivery are more favorable). The click-and-collect model is at the sweet spot of retailers’ economics and the consumer’s willingness-to-pay threshold. It’s also the online model that can most readily accommodate fresh products because it uses retailers’ existing cold supply chains. With click and collect, CPG companies can continue delivering large shipments to distribution centers, in some cases without even knowing whether the products are destined for sale online or offline.

The biggest challenges of this model are in inventory management and, to a certain extent, demand planning. How well CPG manufacturers and their retailer customers share data will be a big determinant in the success of click and collect. For example, the model will disrupt the purchase pathway for some categories, specifically, impulse-sale items sold at the register or in promotional displays. So manufacturers and retailers will need to figure out new strategies to offset any losses.

CPG companies can work with retailers in strategic and tactical ways; for example, in designing e-commerce-friendly packaging (for when click and collect moves to “dark” stores) or in developing sensible procedures for order pickers (to ensure, say, that shelves aren’t emptied by online orders).

Pure Play. Pure-play retailers include companies such as Fresh Direct, Peapod, and Amazon—although with Amazon, the rules and implications are on an entirely different level. (See the sidebar “Amazon: A League of Its Own.”) In general, the biggest complexities of the pure-play model involve master data management and the retailers’ special service requirements (such as Amazon’s common demand that orders of small quantities be delivered within two days instead of the standard five to seven days).

Amazon: A League of Its Own

The e-commerce giant Amazon operates a number of grocery retail businesses—notably Amazon, Amazon Pantry, and Amazon Fresh—that serve different consumer needs. Considering the breadth and volume of Amazon’s channels (the company owns 31% of the online grocery market) and its range of product categories (from perishables to every level of density in shelf-stable items), the opportunities for CPG companies that sell to Amazon can be tremendous.

Yet dealing with Amazon entails all the challenges of dealing with any pure-play entity—but orders of magnitude greater. Amazon’s supply chain requirements are constantly evolving, along with the company’s service offerings. And changes in these requirements are often sudden. Given the company’s vast geographic reach and extensive distribution center network, inventory management for CPG companies serving Amazon can be extremely complex. Demand is often volatile, with wild geographic disparities. Programs such as Prime, which propelled Amazon’s growth, are built on an ironclad guarantee of fast delivery, which means Amazon holds its suppliers to the same high bar in meeting narrow delivery timeframes. A stockout on Amazon can do lasting damage to a brand; the site’s product rankings are based on purchases and traffic, and 80% of Amazon shoppers don’t go beyond the first page of search results. A drop in search ranking thus has an immediate, and sometimes dramatic, impact on sales.

The trailblazing CPG companies in our study emphasized the need for dedicated talent, special attention to master data management, and programs such as vendor-flex in order to succeed with Amazon. These companies work hard to strengthen the manufacturer-retailer relationship, including communicating expectations, challenges, and limitations. Unilever, for example, worked with Amazon to develop a joint business plan and dedicated a full-time employee to scrubbing data. Through such efforts, the company has achieved one of Amazon’s lowest stockout levels.

Amazon’s acquisition of Whole Foods raises many unknowns. If the combination speeds Amazon’s move to innovative store formats or new service models, it could further increase complexity and raise the cost-to-serve for CPG companies. It could also compel brick-and-mortar players to accelerate their investments in e-commerce or to adopt Amazon’s data-driven approach, in which the manufacturer-retailer relationship matters less. That would most certainly complicate life for CPG companies.

To handle the smaller shipment sizes common in the pure-play model, CPG companies need to bolster their warehouse capabilities. This can include introducing process improvements, or new technologies, or new ways of collaborating with their partners, such as vendor-flex programs, which allow the retailer to colocate in the distribution center. Procter & Gamble, for instance, created dedicated space in its warehouses where Amazon employees pick, pack, and ship to consumers. Many CPG companies engage third-party logistics providers to handle picking, packing, and shipping.

Adding e-commerce expertise to the supply chain team to manage these new complexities is a good idea. So is implementing new dashboards and KPIs to track performance.

Direct to Consumer. This model can be valuable in specific contexts: to offer subscription-based sales, to build a brand, or for gifting purposes. But volumes tend to be low and profits elusive because of the high cost of last-mile delivery—and that is not likely to change much. Indeed, the biggest hurdles with this model relate to last-mile delivery: managing and packaging small orders, meeting the fast response times required to compete with pure-play retailers such as Amazon, and deciding whether to outsource last-mile logistics.

The biggest hurdles with the direct-to-consumer model relate to last-mile delivery.

Only a very few survey respondents offer the DTC model: P&G has a branded product page; Unilever has Dollar Shave Club; PepsiCo sells Gatorade from its own website; and vitamin and supplement maker NBTY owns an online retailer. Most CPG companies won’t pursue DTC as a meaningful source of sales.

The Capabilities CPG Companies Need

While grocery manufacturers continue to focus on commercial considerations—which retailers to target, how to market to them digitally, which channels are best—they also need to think about how to address multiple issues in five areas. The requirements, of course, vary from model to model.

Demand Planning. Channel proliferation isn’t the only reason for the increased complexity of demand planning in e-commerce. For starters, online retailers share less demand data. In addition, online sales trends gain momentum faster; more traffic on Amazon raises a product’s ranking, accelerating traffic even more. (Amazon’s dynamic pricing algorithm can also cause spikes in demand.) Yet stockouts, bad enough in traditional retail, can be deadly to an online seller. Even in click and collect, pickers can empty store shelves, frustrating shoppers. Volatility in order volumes is tough enough to manage without the geographic dispersion of orders. With Amazon, in particular, orders are geographically unpredictable; one week they might originate on the East Coast, the next week on the West Coast, as the company balances its internal inventory. And unlike in the offline world, CPG companies don’t have months to work with retailers preparing for promotions.

Stockouts, bad enough in traditional retail, can be deadly to an online seller.

Better demand planning can do more than enhance forecasting accuracy: managing product availability and the online shelf can actually influence demand. The upshot: CPG companies need to develop better ways to understand and respond to demand signals.

Warehouse Operations. E-commerce brings a double whammy: increased service expectations and more case picking and loose picking, owing to smaller order quantities. Even at the current low-volume levels, loose picking introduces considerable complexity. On top of that, lead times are compressed. So manufacturers must consider how to optimize warehouse operations for e-commerce models. The main way—automating loose cases and case picking—is relatively expensive.

SKUs and Packaging. Physical and online channels each have optimal packaging formats. E-commerce requires no-frills, space-efficient packaging that both minimizes shipping costs and provides protection during shipment. But packaging must also meet consumers’ expectations—for example, by being leak proof or made from recyclables. CPG companies therefore need to decide which features and technologies are worth investing in—no minor decision in an era of product proliferation.

Inventory Management. Many e-commerce retailers require smaller, more frequent orders, a condition that raises two broad questions: Should CPG companies and their retailer customers redefine inventory ownership on the basis of product velocity? And what must CPG companies do to manage master data issues?

Transportation. E-commerce introduces even more fragmentation to an already fragmented distribution network. That means greater network complexity overall. The reduction in order size has big implications: if online sales grow, the reduced scale in existing transportation networks could drive the costs of transporting goods to brick-and-mortar customers way up—or service levels way down. So CPG companies need to balance cost, quality, and agility. For the direct-to-consumer model, they must figure out how to manage last-mile delivery, which can cost two to three times as much as the product itself.

Trailblazers’ Smart Moves

Undaunted by the lower profitability of e-commerce today, e-commerce trailblazers are banking on a longer-term payoff: brand building, subscription revenues (from the DTC model), and, ultimately, the opportunity to get in on a pocket of growth in an otherwise low-growth industry. At a minimum, these companies are staying flexible so that they can adapt quickly (for example, by using third-party logistics partners) and are tracking omnichannel online sales.

But most are doing much more. P&G and PepsiCo, for example, have been running DTC websites for some time and use them to learn more about online shopping behaviors. Some manufacturers offer customized or personalized products through their DTC sites; take, for example, Mars’s My M&Ms and Oreo’s Creation Contest. Others are acquiring online-first businesses, such as Unilever, with its purchase of Dollar Shave Club. And still others are investing in warehouse automation to prepare for a future of smaller orders. (See Exhibit 2.) As a group, though, the vast majority of trailblazers are implementing many different initiatives and activities to meet the supply chain challenges e-commerce presents.

What All CPG Companies Should Be Doing Now

Clearly, the trailblazers have a head start; the CPG manufacturers waiting on the sidelines should take the following steps to best position themselves for e-commerce.

Align the organization on its e-commerce ambitions. First and foremost, the executive team must clarify its near-term e-commerce ambition and decide which model or models best suit it, considering the company’s product portfolio and its supply chain characteristics and strengths. For instance, a maker of frozen foods might focus on selling to click-and-collect purveyors as well as to a few pure-play operators that are able to store and ship frozen items. A skin care manufacturer might create its own direct-to-consumer subscription service.

Identify the supply chain gaps to support the model (or models). Once CPG companies choose the most suitable e-commerce business models, they need to pinpoint the gaps in their supply chain infrastructure and capabilities.

CPG companies should make some relatively inexpensive, no-regrets moves right now to ramp up their e-commerce supply chain capabilities.

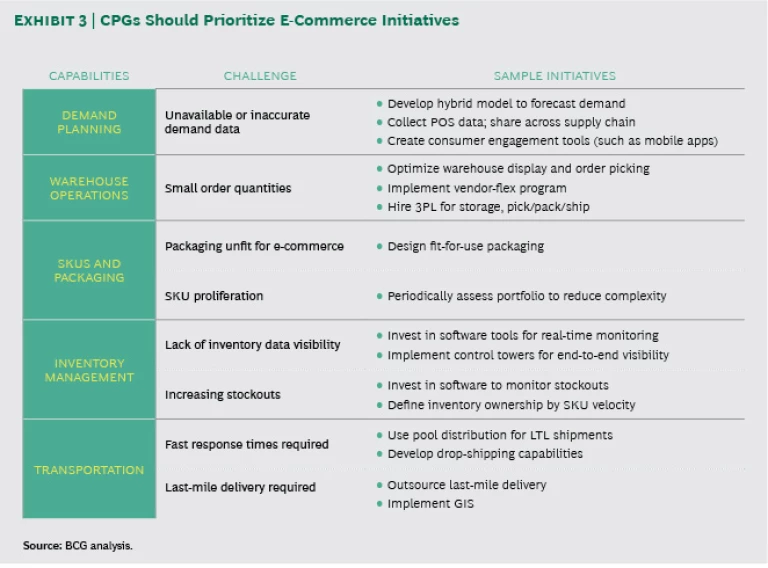

Prioritize the e-commerce initiatives that will yield the biggest bang for the buck. Finally, companies need to set their supply chain priorities. For their targeted e-commerce model or models, where are they weakest? What initiatives would help fill the most critical gaps? Exhibit 3 shows a sampling of initiatives in the key areas.

All CPGs should make some relatively inexpensive, “no-regrets” moves right now to ramp up their e-commerce supply chain capabilities. At the very least, they should list their products on all the pure-play sites. They should also create an e-commerce team within the supply chain group and develop KPIs to track e-commerce performance. Working with Amazon to synchronize master data is a must. Finally, CPGs should experiment manually with smaller pick sizes so that they are ready to invest in automation when their e-commerce sales reach a certain scale.

Grocery e-commerce is still in its infancy, but by all indications, it’s likely to drive a significant portion of the industry’s growth. As consumers do more of their grocery shopping online, more change and adaptation will follow. In the digital world, where critical mass is won quickly—and, once won, is hard to dislodge—CPG companies cannot afford to sit out the evolution. To ensure your supply chain is up to the task, forge ahead with no-regrets moves. At the same time, secure alignment among leadership team members. The surest path to e-commerce success starts with determining where to focus your energy and investment in the critical next few years.