Many investors believe that conglomerates as a whole are worth less than the sum of their parts. A review of historical stock market data shows that this “conglomerate discount” applies about 55% of the time. This means, of course, that a little less than half the time the discount does not apply. More important, a select group of diversified companies trades at a premium. Why do these premium conglomerates outperform their peers in TSR, year in and year out?

The answer lies in their adherence to strict criteria when choosing businesses for their portfolios and the rigor and consistency with which they apply their core operating principles. Viewed in this light, premium conglomerates are not truly diversified—even though their businesses may vary in terms of markets, products, or customers. Specifically, premium conglomerates invest in companies with similar competitive strategies and underlying economics. Then they put systems and structures in place to ensure that the businesses are all run the same way and that line managers are strictly accountable for results. In other words, each premium conglomerate has a unique, consistent footprint that drives its success.

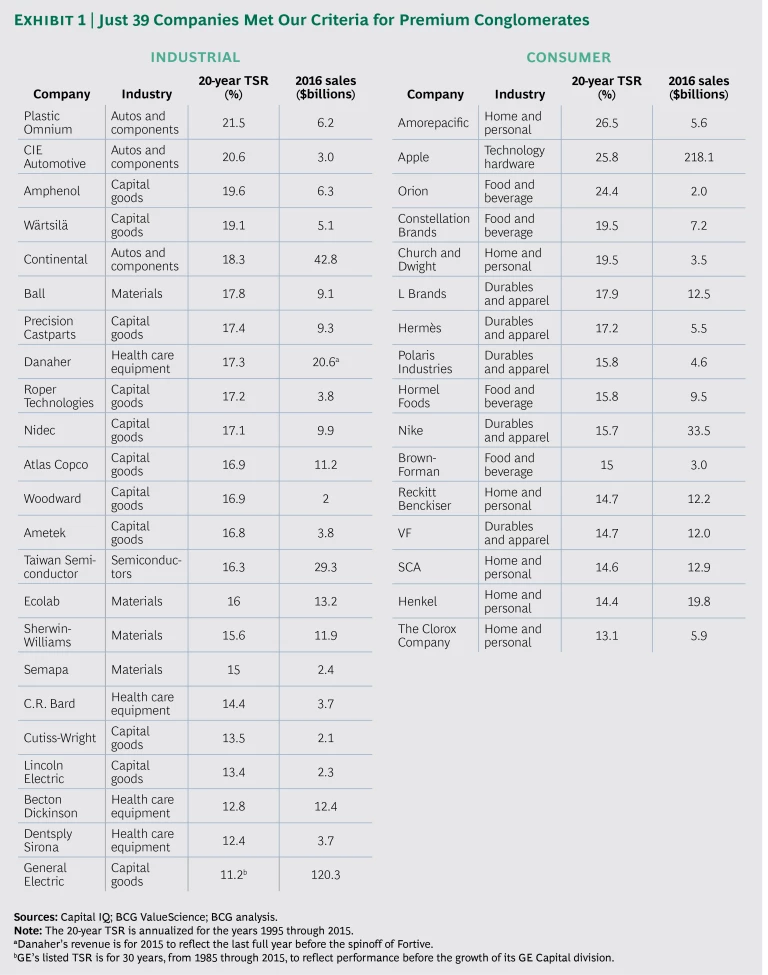

To identify premium performers, we analyzed 20 years of stock market data. Because we were looking for sustained success, short-term TSR wasn’t an adequate measure—many TSR leaders in any given quartile or year are simply bouncing back from poor performance in an earlier period. We established three criteria for premium conglomerates. These companies must have had:

- Top-quartile TSR for 20 years

- Top-quartile TSR in at least two five-year periods during those 20 years

- No bottom-quartile TSR in any five-year period during those 20 years

Our analysis revealed that just 39 publicly traded industrial and consumer conglomerates met these criteria. (See Exhibit 1.) Some, including General Electric (GE) and the Clorox Company, are household names. Others are far less well known. And many of these highfliers run nonglamorous, even mundane businesses.

The Top Performers

The companies that made our list showed strong, steady increases in revenue growth—and their profits grew even faster. What’s more, they managed to sustain their strong performance over a 20-year period through successive CEOs, economic downturns, and disruptive changes in technologies, markets, and competitors. They generally pay dividends but retain more cash than most publicly traded companies, using it to fund internal growth. As a result, 70% of their growth is organic. Still, mergers and acquisitions are important, accounting for the remaining growth. The companies on our list are serial acquirers, spending, on average, 3.6% of their market cap per year on acquisitions (one and a half times as much as the average public company). And they are consistently able to improve the performance of the companies they buy.

Danaher is a good example. The highly diversified company sells centrifuges, dental implants, fuel dispensers, and water fillers to varied buyers, such as research labs, the health care industry, service stations, and utilities. In 1998, Danaher acquired Fluke, a maker of electronic test and measurement instruments. Fluke’s operating margin the year prior to acquisition was about 8%. Less than five years later, it was more than 20%.

The degree of success and longevity that these premium conglomerates have achieved is exceedingly rare in today’s fiercely competitive business environment. Digging deeper, we found two reasons for their remarkable performance: a portfolio of companies that have a consistent business model and a “no excuses” culture of accountability. Although some diversified companies may have one or the other of these key dimensions, premium conglomerates have both.

Consistent Business Model

Premium conglomerates focus their portfolios on companies with the same underlying business model and competitive economics. You won’t see efficiency-oriented, low-cost players mixed in with high-touch providers of superior service. Or fast-moving consumer products companies mixed in with those that sell big-ticket items with lengthy sales cycles. Or high-volume manufacturers mixed in with companies that make a small number of precision engineered, customized products. Simply put, premium conglomerates make a point of grouping apples with apples in their portfolios.

Some of the factors that leading performers evaluate and seek to align include price range, degree of customization, customer type, sales channel, service levels, production volume, number of competitors, product life cycle, brand equity, degree of regulation, asset intensity, and demand volatility. Premium conglomerates recognize that, when seen through this lens of fundamental similarities, companies in seemingly different lines of business can be run in virtually the same way.

Premium conglomerates recognize that companies in seemingly different lines of business can be run in virtually the same way.

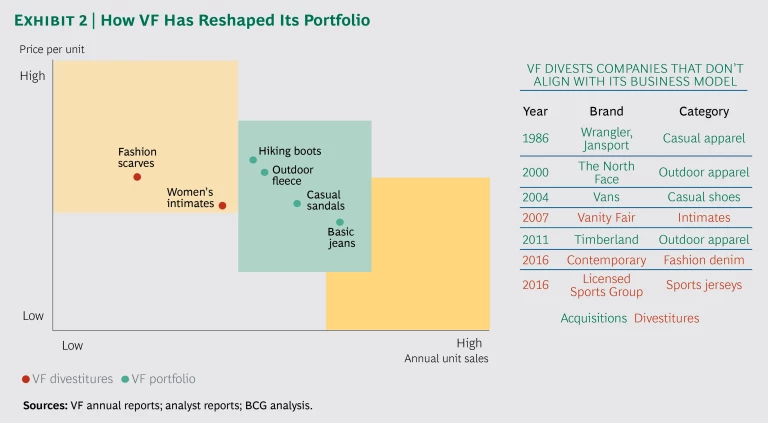

VF Corp. (formerly Vanity Fair) is a case in point. Once synonymous with lingerie, VF now sells jeans, backpacks, outerwear, and footwear under brands including Eastpak, the North Face, and Timberland. The companies in VF’s portfolio sell high volumes—more than 500 million units per year—of midprice merchandise. Other characteristics of the VF business model include nontrendy products that are slow to change, a narrow assortment of merchandise, low asset intensity, a focus on large retail customers, and minimal spending on advertising and promotion. Combined, these factors boost gross margins and minimize expenses, leading to a consistently profitable business model—and generating cash for acquisitions. Over the years, VF has divested companies that don’t align with this model, such as its namesake lingerie business, as well as makers of scarves and fashion denim. (See Exhibit 2.)

GE and Finland-based Wärtsilä take a very different approach. Both companies make large, highly engineered capital goods with long life cycles. GE’s aircraft engines, power turbines, and medical scanners are sold in global markets with a limited number of competitors. The same is true for Wärtsilä’s marine engines and power plants. Each company aims to be first or second in its market. Other similarities in their business models include a low volume of high-priced products, multiyear product development projects, direct sales to the end user, and a very intense effort to capture aftermarket service revenues. In fact, services account for as much as 50% of total revenues and an even higher share of profits.

Different still is the business model that underlies Ametek’s portfolio of companies, which manufacture connectors and other devices for the high-tech and consumer electronics industries. Although the products are low priced, they are standardized and must be made to established specifications, which creates a ready platform for competitors. As such, Ametek must keep a strong focus on profitability. The company ensures that it will retain a cost advantage by establishing scale, and it is ready to respond when technologies change in order to quickly gain an advantage in the new space. Other characteristics of the business model include fragmented applications and end markets as well as a mix of direct sales, dealers, and retailers. Market share by product type is critical to this business model, and the Ametek companies focus on that goal.

By sticking to similar business models and underlying economics, premium conglomerates can explore unexpected paths for creating growth and value.

A “No Excuses” Culture of Accountability

The second key dimension of premium conglomerates is ruthless accountability. The companies on our list make very clear who owns the P&L. It may be the business unit leader, the global brand manager, or the plant manager. But in all cases, there is one line manager responsible for performance, and that person must hit his or her sales and profit targets. Consistent year-to-year improvement and increasing year-on-year profits are expected—no matter the state of the global economy. Targets are absolutely nonnegotiable, and accountability is absolute. Failure to perform has serious consequences. The following statements typify what we heard again and again from both current and former employees of premium conglomerates:

For the companies on our list accountability is absolute. Targets are absolutely nonnegotiable, and failure to perform has serious consequences.

- “If you miss targets for more than two quarters, you’re fired.”

- “Your operating profit goal is 15%, regardless of competitive dynamics.”

- “It’s an up or out culture. The system pushes a lot of people out.”

Goal setting tends to be a simple process. Rather than delving into the environment and competitive situation to assess how much growth and profitability are possible, these diversified companies set incremental improvement goals—usually along the lines of “earn 10% more than last year.” On the rare occasion that a major economic shift (such as falling oil prices) causes missed targets, the baseline resets and performance goals start to escalate again. Compensation structures typically reinforce accountability. Top performers can get bonuses of up to twice their salary, and compensation is variable at all levels.

Premium conglomerates have metrics, training, reviews, and tools in place to support and reinforce this “no excuses” culture. For instance, packaging manufacturer Ball has embraced the economic value-added (EVA) approach, training all employees in the philosophy and setting all employee and business unit targets in EVA terms. Household products company Church & Dwight sets targets, cascades priorities, and trains all employees on TSR as a metric.

The companies on our list are committed to HR development and provide support in this area to all businesses in their portfolios. Most have an HR management system to ensure that the best people are identified, trained, and deployed in ways that enhance their career development. Because all businesses have the same culture and are run in virtually the same manner, managers can move from one company within the corporate family to the next fairly seamlessly. Premium conglomerates also have knowledge management systems in place to codify company learning and best practices.

Finally, most premium conglomerates have a continuous improvement process, such as Kaizen or Six Sigma, in place to ensure forward momentum. GE’s Work-Out approach, for instance, brings together cross-functional teams to work through process improvement problems.

Few diversified companies attain the long-term growth and profitability of the top performers on our list. What sets the members of this premium group apart is their unwavering commitment to a set of core operating principles and their ability to instill a culture of accountability. Drawing on the combined power of these two dimensions, premium conglomerates achieve sustained success—and avoid the conglomerate discount that plagues so many of their peers.