Why do companies fail or fall behind their rivals? Among the many reasons, three stand out. Some companies miss a major strategic shift or industry disruption. Others see a big change coming but fail to develop the right strategy in response. And some define a winning strategy but are not able to implement it effectively. To increase their odds of success in today’s turbulent environment, leading companies are complementing their traditional annual strategy-setting process with something more dynamic. We call it always-on strategy.

Always-on strategy gives companies a systematic way to scan for signs of disruption and explore unexpected changes to the strategic environment. Companies identify the most pressing strategic issues and regularly engage senior leaders in formulating a response. And they carefully monitor the progress of strategic initiatives to increase the speed and impact of execution.

Although the benefits are clear, companies are often uncertain about how to introduce always-on strategy into their strategic planning process. In our view, always-on strategy should be designed to complement, not replace, the annual process. By integrating always-on strategy into a streamlined process, a typical company can make strategic planning less rigid and sequential and more agile and continuous.

One company, for example, uses monthly reviews of a “watch list” to track and, if necessary, escalate strategic issues that were flagged during the annual planning process. The company also regularly reviews the progress of strategy implementation against KPIs, allowing it to spot deviations easily and take corrective actions rapidly.

Leading companies are experimenting with various aspects of always-on strategy, but we have yet to see any company take a comprehensive, systematic approach. This article—using examples drawn from our interviews with executives across industries—offers a review of best practices and outlines a comprehensive process.

The Case for Complementary Strategic Processes

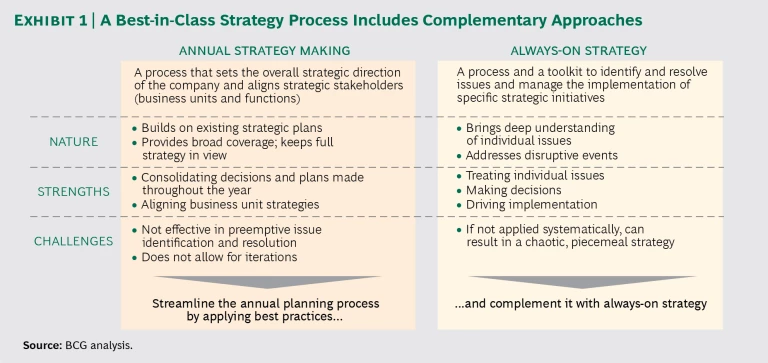

A best-in-class approach to strategy making includes both annual and always-on components. (See Exhibit 1.)

The annual strategic planning process at most large companies follows a familiar cycle: corporate strategy is defined in the second quarter of the year, business unit strategies are formulated and aligned in the third quarter, and budgeting and communication occur during the fourth quarter. Despite their prevalence, annual planning processes have few fans among executives. Many executives criticize those processes for being overly bureaucratic and poorly suited to today’s fast-changing markets. Many also complain that participants in the strategy-setting process tend to elevate form over substance, investing time fulfilling procedural requirements at the expense of rigorous content discussion.

Companies can improve their existing strategy-setting practices in several ways. (See Four Best Practices for Strategic Planning , BCG Focus, April 2016.) But even a well-designed, question-driven annual process does not give executives a chance to monitor and discuss strategic issues and iterate on solutions throughout the year. The annual process typically provides, at most, three main opportunities to discuss strategy decisions: at the beginning of the cycle, when the long-term strategic direction is set; at a midyear review, when options are validated; and at the end of the cycle, when strategies are approved and fed into the budget process. Outside of these fixed windows, executive teams rarely block time for discussing strategy; as a result, the process for adjusting it is ad hoc and inefficient.

Always-on strategy complements the annual process by giving senior leadership a regular forum in which to monitor and discuss issues that warrant continual attention, including those identified during the annual process and during the course of the year. The always-on process is particularly well suited to addressing issues that span multiple business units (such as a common technology platform), lie outside the scope of existing businesses (for example, growth into adjacent markets), or are too far-reaching to address at the business unit level (such as downstream integration). However, companies must apply always-on strategy systematically—to ensure that executives focus on the highest-priority issues, push for issues to be resolved, and effectively coordinate the activities of the annual planning process with those of the always-on forums.

A Systematic Approach to Always-On Strategy

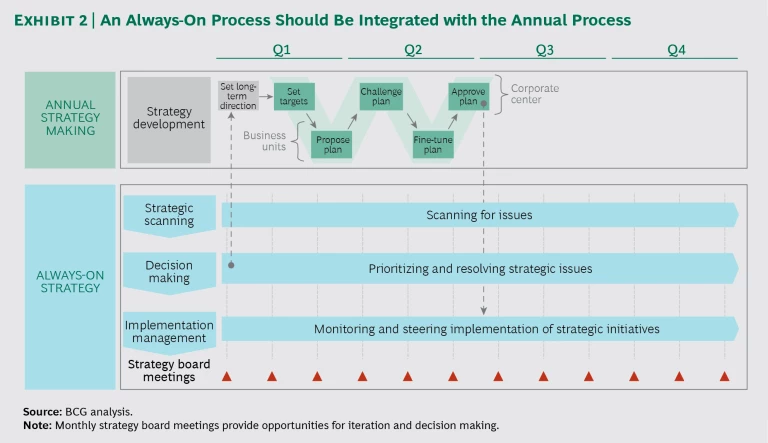

Always-on strategy, as integrated with the annual process, has three components: strategic scanning, decision making, and implementation management. (See Exhibit 2.) The company must create a strategy board comprising the CEO and members of the executive team to lead this approach.

Strategic Scanning

By continually scanning internal and external sources, a company can quickly identify potential strategic issues. Although it is most important to be alert to signals related to the company’s strategic themes, the scanning effort should also target developments that could indicate industry disruption. To avoid a “fishing expedition,” the company should focus on factors that are vital to its competitive advantage. For example, executives might gather information to forecast how specific megatrends will affect customers’ economics and priorities, examine patent and venture-funding data to reveal emerging technologies that could complement or substitute for existing technologies, or survey the sales force in developing markets to identify startups that could pose a threat.

Various approaches can uncover emerging issues, including crowdsourcing initiatives and cross-functional forums. A committee of external and internal experts can also support the scanning effort. For example, a software company has created a team of leaders and analysts from its marketing and strategy functions to ensure that market insights inform strategic discussions.

The chief strategy officer (CSO) and the strategy team are ideally positioned to identify issues from the top down, both in the business units and externally. They can also provide a structure and tools to capture and filter information from the broader organization, such as data from the customer or supplier interface. A telecommunications company, for instance, shares its watch list of strategic issues with local strategy teams and solicits input on the topics.

Decision Making

To assess the signals detected by strategic scanning and decide on the appropriate responses, a company must create a strategic issues list, examine the issues through dedicated projects, and iterate on solutions.

The strategy board vets issues for inclusion on the list and ranks them so that executives can direct their attention to the issues that matter most at a given time. Saturating management’s attention with too many issues often results in an ineffective, piecemeal approach to strategy and may lead to poor decisions.

Issues can be prioritized according to the value at stake, their degree of uncertainty, and the challenges of implementation. The most important topics are those that relate to the key risks, challenges, and opportunities highlighted in existing strategic plans. For example, an industrial goods company prioritizes its issues list to reflect the “must-win battles” specified in its overall plan.

A company can also conduct interviews within its organization to reveal the principal threats and opportunities, both internal and external, and identify the main industry trends. Additionally, a company can develop scenarios of possible industry developments and then identify the most urgent issues that would arise from them. Potential changes warrant more urgent attention if, for example, the expected impact on the company and its strategy is high, the changes are hard to predict or are unfolding at a rapid pace, or the related implementation efforts promise to be complex and costly.

For each issue, the strategy board should designate a sponsor, ideally someone from the executive team, to lead a project that examines the topic in detail. By establishing a dedicated project, the company allows the examination of each issue to proceed on its own timeline and to include the iterations needed to define a solution. Each project should receive the necessary resources and staffing, including the relevant line expertise. In addition to ensuring that expertise is available to support decision making, involving the line organization makes it more likely that the initiatives emerging from a project will be implemented. To complement and challenge the internal understanding, the strategy team should selectively involve external stakeholders (such as clients, suppliers, and experts).

During its regular meetings, the strategy board should assess the progress of each project, remove roadblocks, and decide on the next steps. Depending on the project, these steps might include another iteration on solutions or implementation of a strategic initiative.

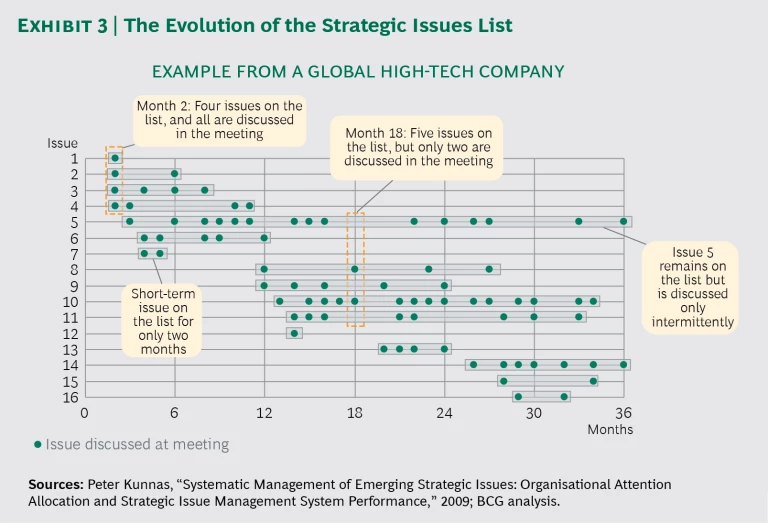

The issues list evolves as new issues are identified in the scanning process and old ones are resolved through the dedicated projects. (See Exhibit 3.) Companies should expect some issues to remain on the list for many meetings as stakeholders explore the issues, track their evolution, and iterate on responses. To avoid overloading the agenda of the strategy board meetings, the strategy team should remove low-value items promptly. Feedback processes should be in place to integrate the management of the issues list with strategic scanning and implementation.

Strategy Implementation Management

To capture the benefits of always-on strategy, following through on implementation is essential. We see many examples of formerly great companies that accurately predicted changes but lacked the fundamental ability to implement a new strategy in response. Because executing a shift in strategy typically requires major changes to an organization’s design and capabilities, implementation often falls short.

By regularly monitoring and managing the implementation of initiatives, the strategy board helps to identify problems or deviations that require corrective action and, in general, helps to promote the success of initiatives. The board should use KPIs, specific milestones, and other easy-to-apply criteria to facilitate its work. The board should also escalate issues back to the company’s strategic issues list, if necessary, so that the plan can be reviewed and potentially revised.

A multinational hospitality company has set up a dedicated strategic business management team at the corporate level to act as a program management office (PMO) and, on a monthly basis, monitor initiatives’ progress against KPIs. The team also manages the strategic issues list and removes or deprioritizes issues as needed. The company is instituting a similar PMO approach to strategy implementation in its regional and functional units.

Putting in Place the Enablers

Always-on strategy is not a complex process, but to succeed it requires a few key enablers.

Strategy Board and Meeting Cadence

In addition to creating a strategy board, the company must establish the right cadence for its meetings. To provide enough time for in-depth strategy discussions, the board should meet for at least a half a day every month. Each of the three components of always-on strategy should receive its fair share of time, with an emphasis on content discussions that address the full issues list or touch on specific issues. Only a limited amount of time should be spent discussing process.

Governance and Organization

The CEO should own the work of always-on strategy, just as he or she owns strategy in general. The CEO’s ownership ensures that strategic issues receive the required attention and resources. Moreover, the CEO is the only person with the formal authority to prioritize issues. The CSO should assume operational leadership of both the annual planning cycle and the always-on process. For the always-on process, this should include an active role in identifying and prioritizing issues and in setting the agenda for strategy board meetings. For some companies, these responsibilities may require enlarging the mandate of the CSO and the strategy team. The CSO and the team can also provide valuable help to strategy projects, including staffing to support division heads and their line organizations with analyses and project management.

The same governance model can be used to apply the always-on approach at regional, functional, and business unit levels. A unit’s head and strategy leader take on responsibilities analogous to those of the CEO and CSO. For example, a leading telecommunications company has cascaded the always-on model down to its product and sales and marketing units.

Integration with the Annual Process

To institutionalize the complementary nature of annual and always-on planning, the company should align and coordinate the processes and allocate the roles related to each activity. The strategy board can make individual content decisions and plans during its always-on planning meetings and use the annual process to consolidate them. This allocation reduces the number of decisions required during the annual planning windows, allowing the executive board and board of directors to use these periods to review comprehensive plans. The outcome of the annual planning cycle can then feed back into the always-on strategy process, either as issues for further analysis and decision making or as initiatives to be monitored through strategy implementation management.

The turbulence in the business environment shows no sign of abating. To survive and thrive, companies need an approach to strategy making that promotes timely and value-maximizing decisions and ensures that the decisions are fully implemented. Always-on strategy is not a complex process, but it brings a fundamentally new mindset to strategy making. To get started, the CEO must make the decision to set aside a half a day each month to focus on strategy. The return on the time invested can be significant as companies respond more quickly and effectively to major changes in their markets.