This article is an excerpt from The Most Innovative Companies 2016: Getting Past “Not Invented Here,” (BCG report, January 2017).

The Most Innovative Companies 2016

- Innovation in 2016

- Casting a Wide Innovation Net

- Bringing Outside Innovation Inside

A few years ago, Brooks Automation, a leading supplier of equipment and components to the semiconductor industry, was seeking new revenue streams. Cyclicality and slowing growth prompted the company to look outside its core business. Conventional analyses, based on such metrics as market size and the ability to command a price premium, could rank the attractiveness of new markets, but they couldn’t answer a fundamental question: If competitive advantage is driven by some combination of position and capabilities, in which adjacent markets would Brooks be poised to win?

New techniques could help answer that question. Using advanced analytics to sift through massive amounts of data from multiple sources, the company rapidly homed in on an idea. There was a clear theme in Brooks’s most-cited patents: the company had exceptional capabilities for creating and controlling very cold environments under a vacuum—and for handling materials within them. This insight made it much easier to evaluate various adjacent markets. The storage of frozen tissue samples quickly emerged as highly promising. The existing storage solutions for precious and perishable tissue samples were far from sophisticated. Brooks’s expertise could make a huge difference. But the life science industry differed markedly from semiconductors. This raised the next question: What was the best way to enter that market?

Brooks sought to speed its entry into the new sector with a series of small acquisitions of life science companies that had complementary expertise, technology, and customer access. This exploratory approach enabled Brooks to expand carefully and learn along the way. The initial results of this strategy have been positive. The new life science business continues to grow and now approaches 20% of the company’s revenue. And the many new product and service opportunities in the segment offer significant room for growth.

Tapping—or Missing—External Sources

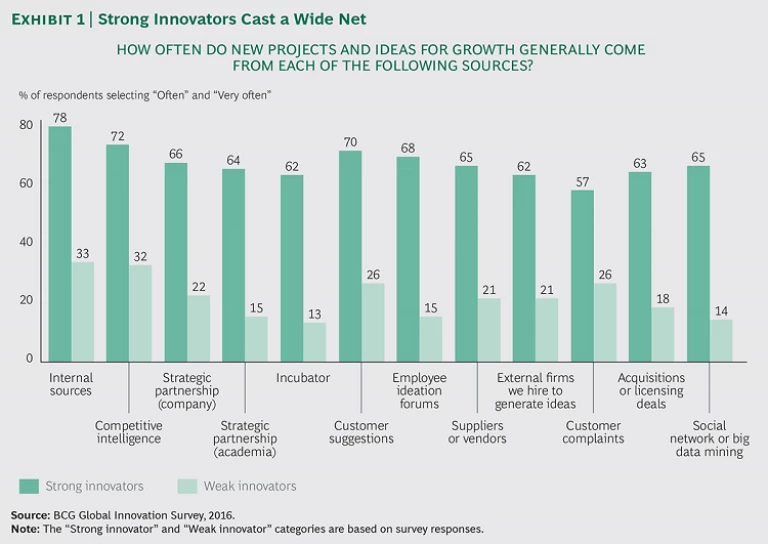

The self-described strong innovators in BCG’s 2016 global survey on the state of innovation are far more likely than the self-described weak innovators to cast a wide net as they look for potential innovations. (See Exhibit 1.)

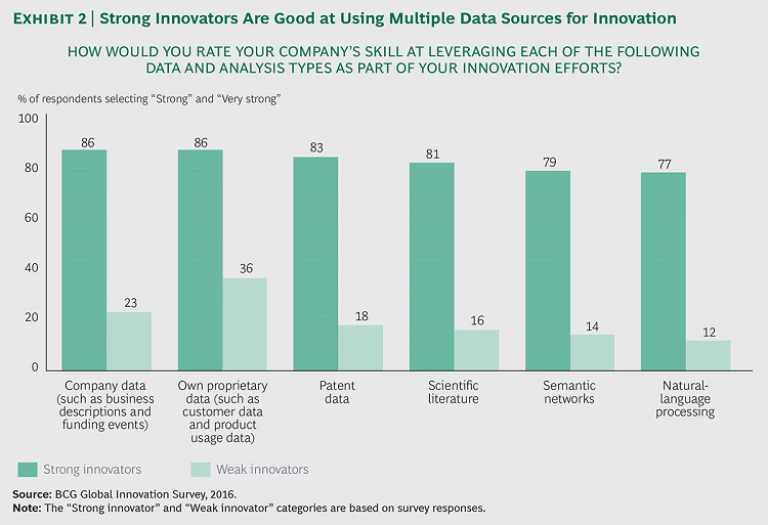

They are also substantially better at using multiple data sources—not just their own but also external sources such as global patents, scientific literature, semantic networks, and venture funding databases. (See Exhibit 2.)

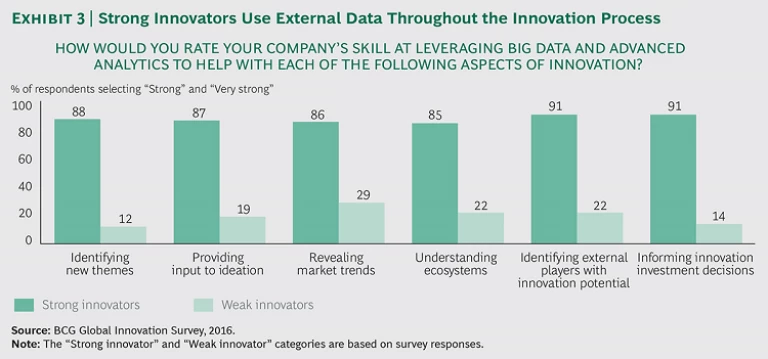

Moreover, strong innovators use external data in multiple phases of the innovation process, from identifying promising new ideas to making investment decisions. (See Exhibit 3.)

The best of the strong innovators are adept at leveraging external innovation for many purposes:

- Finding the next big thing

- Avoiding disruption by unearthing emerging technologies and innovation trends

- Linking with startups and leading inventors to accelerate innovation

- Building networks of collaborators to stay on top of leading-edge technology

- Assessing the impact of new technologies on the business

- Identifying adjacent growth opportunities

- Attaining a position of technology leadership

As Brooks discovered, a huge amount of data is available to help innovators shape and pursue their innovation strategies. But this in itself causes problems. The first is identifying what data exists and figuring out where to find it. The second, and usually much bigger, challenge is sorting, organizing, and gleaning usable insights from millions of files (or pages) from disparate depositories, databases, websites, and other sources. Plenty of companies mine patent data, for example, to keep track of the IP their competitors are developing. It’s a far different order of complexity to pinpoint commonalities and directions when the data comes from multiple sources such as global patent filing trends, venture funding databases, scientific literature, and expert industry opinions.

Harnessing Innovation Analytics

As the amount of data has burgeoned, so has the sophistication of the tools available to analyze and visualize it. For example, BCG’s Center for Innovation Analytics uses a suite of tools and approaches to tap into multiple public and proprietary sources to help companies develop answers to tough questions about innovation and growth. These can pertain to identifying adjacent opportunities (including novel uses of a company’s existing capabilities), finding white-space opportunities, monetizing a company’s own intellectual property, identifying and screening potential acquisition targets and venture partners, and gaining an understanding of new technologies that represent a potential competitive threat.

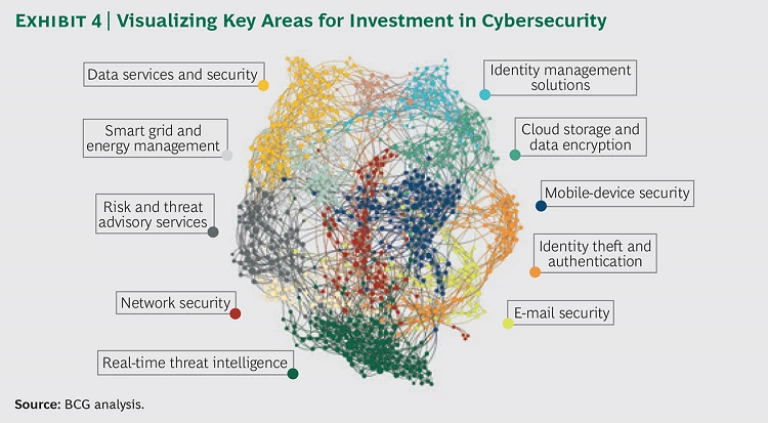

Consider a hypothetical company that has an interest in moving into cybersecurity. It might want to begin by understanding the shape of investment in the sector: the key applications, the underlying technologies, the most important players in both technology and funding, and the changes in investing trends. This requires a lot of data: from 2011 to 2015, venture firms invested more than $17 billion in nearly 1,000 cybersecurity-related companies. Exhibit 4 offers one example of how this data might be visualized and analyzed. This semantic analysis (which looks for commonalities—of words and concepts, for example—in unrelated sources of unstructured data) reveals ten distinct technology subsectors within cybersecurity, such as identity management and real-time threat intelligence.

This high-level view is just the start; it’s also possible for executives to drill down to information on individual companies in order to spot whether and where rivals are making investments, or to identify attractive partnership or acquisition candidates. Companies can combine insights from funding data with patents, social media, scientific publications, and a variety of other sources to make informed strategic decisions.

For companies in industries undergoing technology-driven evolution or disruption, innovation analytics can provide a critical means of staying abreast of changes and determining which new technologies to apply to their own innovation efforts. A major chemical company has used innovation analytics to better understand opportunities in biorenewables, for example. And a leading telco used it to inform its new-product development by mapping the technology innovation in user interfaces among new entrants, incumbents, other competitors, and academics.

Innovation analytics can be applied in a wide range of circumstances to gain insights that help set direction and strategy. In 2016, leaders from Microsoft, the Washington Roundtable, and the Business Council of British Columbia met to explore the possibility of greater economic collaboration between the greater Seattle and Vancouver regions. The project was inspired by the rise of innovation hubs around the world, and business and government leaders in both Seattle and Vancouver saw great promise in building on the region’s strong foundation of innovators and innovation assets.

Innovation analytics surfaced some surprising reality checks. Data from LinkedIn, for example, showed low connectivity between individuals in Seattle and Vancouver; talent did not flow freely between the cities. For LinkedIn members in Vancouver, connections to members in Seattle accounted for less than 1% of total connections; for members in Seattle, connections to those in Vancouver accounted for only 0.4% of connections. Data from Thomson Reuters showed that educational institutions in both cities trailed other areas in academic citations. And data from investment databases showed that the availability of local capital was an additional issue. These and other analytics-driven insights helped shape the challenge facing the two cities and give direction to the efforts to build a more vibrant innovation corridor.

The most innovative companies are data-driven innovators. By using the right tools, just about any company in any industry can harness data, including from sources that have not been readily accessible in the past, and use the insights that emerge as the basis for novel products and approaches.