If they are successful, digital transformations result in digital organizations—companies whose strategies, business and operating models, and cultures have digital technologies and capabilities at their core. Digital ways of working shape everything that these organizations do. In the media business—one of the first to undergo digital disruption—most legacy companies started the transformation to digital organizations years ago. But establishing a functioning digital operating model requires a big leap, one that relatively few media companies have taken so far. Most legacy companies in this business face two industry-specific obstacles in their efforts to meet the digital challenge: their lack of digital, data, and multimedia expertise and the institutional lack of clear decision making, accountability, and effective interdisciplinary collaboration. True digital organizations are still, for the most part, in companies that are digital natives.

Companies that start with a well-functioning operating model have an advantage. An operating model characterized by clear processes, decision rights, and goals and metrics confers the ability to make fast decisions and move quickly—both fundamental to operating effectively in digital ecosystems. And digital operating models enable adaptation of, or changes to, business models more rapidly than traditional management structures burdened by layers of review and approval. They also allow companies to automate both routine and not-so-routine operations to achieve new efficiencies, increase productivity, and reduce costs—all priorities for investors in today’s capital markets.

Companies that start with a well-functioning operating model have an advantage.

Several years ago, BCG presented a transformation game plan for print media companies. (See Transforming Print Media , BCG Focus, December 2012.) In 2016, we observed that most companies had made the near-term moves to raise cash for the transformation journey and had taken medium-term steps to establish new lines of business, primarily in adjacent areas. (See “ The New News on Print Media Transformation ,” BCG article, June 2016.) Many companies have adapted their business models, rethinking customer relationships, identifying new revenue streams, and creating and improving digital products and services. But most have yet to design and organize around operating models that are truly digital. They struggle to translate digital strategies and visions, particularly with respect to the role of the media product, into digital ways of working. Processes are muddled, roles and functions vague, and decision rights subject to disagreement and dispute. Disagreement can be rife when it comes to addressing traditional revenue sources and current cost centers, as well as identifying the steps necessary to make digital content and distribution profitable. It is perhaps most significant that these companies have not made clear who, in the new digital way of doing things, is in charge.

The transition to a digital organization is neither an optional improvement nor an HR exercise. It is requisite for getting better output from limited resources, accelerating decision making, attracting talent, and improving engagement and retention across the company. Rank-and-file employees often feel much of the pain that is the result of companies’ sticking to the “old way.” They complain that decisions become mired in endless debate, that time is wasted in trying to resolve issues that involve multiple stakeholders, and that there is a lack of empowerment lower in the organization. Making the full break and establishing a truly digital way of working require engagement and alignment across the senior executive team.

Developed on the basis of our recent work with media businesses and interviews with senior executives at more than 30 companies, here is our assessment of the challenges in this critical phase of the digital transformation journey.

Establishing a truly digital way of working requires engagement and alignment across the senior executive team.

Organizational Transformation Has Stalled

First, a question: Why do companies struggle with organizational transformation? There are several reasons, including those that face all kinds of companies. One constraint is the lack of relevant skills. Media company employees are talented, but their skills are not necessarily technical or digital. Another is the need for speed and interaction among previously siloed functions with clearly defined lines of responsibility, especially with respect to the collection, processing, and use of data. (See Designing Digital Organizations , BCG Focus, December 2016.) For companies that are used to operating in silos, such change is both organizational and cultural. The cultures of media companies were built on a bifurcated kind of model that emphasizes editorial quality and creativity on one side and revenue generation on the other—and little or no interaction. People and organizations, as we know, fear and resist change. Implementation, therefore, is difficult.

For many media companies, the first attempts to organize digitally took the form of creating a new position, borrowed from the tech industry: the product manager. Traditionally, media companies’ editorial or production departments concerned themselves with creating or producing news or entertainment content, and the advertising and subscription functions focused on generating revenues. The fast-rising tech companies that disrupted traditional media organized differently: product managers oversaw the development, marketing, and sales of digital products such as streaming music and video, games, aggregated content, and location-based services. As traditional media companies “went digital,” they, too, appointed product managers to spur the development of digital products. But, in many cases, these roles were poorly or incompletely defined, and they encompassed parts of functions on both sides of the existing divide between editorial content and marketing and sales, causing executives and staff in both old and new positions to question where they stood in the resulting organization. A who’s-in-charge battle ensued.

Transformational Pain Points

Our research examined multiple types of media organizations: traditional news companies (print, electronic, and digital—all of which now offer some combination of off-line and online products), traditional magazine publishers (all of which, again, “publish” both online and offline), digital pure-play “publishers,” and media subscription services that offer content on a paid or advertising-supported basis.

We found that plenty of media company operating models still lack clarity and focus and that, as a result, companies encounter a number of common pain points that lead to slower decision making, friction across functions, and an undermining of the broader digital transformation. These pain points include the following:

- Poorly defined links between strategy and operations

- Ambiguous roles and decision rights

- Missing or loosely defined cross-functional processes that streamline operations and foster cooperation

- Inconsistent goals and metrics—both individual and organization wide—and indistinct links between goals and metrics and performance

- Culture that remains rooted in the old way of doing things

- Misalignment of the organization structure and new digital roles

Many of these problems stem directly from lack of clarity about strategy and vision, coupled with uncertainty about how to structure the organization to deliver products. As a result, media companies that are transforming still face two big operating challenges: one, making decisions, developing new strategies, and implementing plans at digital speeds, and two, bridging (or eliminating) organizational silos that inhibit effective use of data and development of digital products and services. Until these companies resolve the uncertainties, the battle over who’s in charge will undermine decision making and impede their progress.

Four Operating Models Emerge

Our research shows that companies that have successfully executed organizational transformation have implemented one of the following four operating models:

- Content led

- Product led

- Revenue led

- Hybrid

Each of the four has significant implications for how the company organizes and works. The primary determinant for each is the company’s strategy and vision, which is rooted in the company’s core beliefs about its business, mission, and customers.

Our research shows that companies that have successfully executed organizational transformation have implemented one of four operating models.

Content Led

As the name suggests, content-led companies produce distinctive—and sometimes iconic—content for which there is limited competition: customers who value reporting by the Guardian or Slate, for example, or photos and stories created by National Geographic, are not satisfied with substitutes; HBO has developed a well-deserved reputation for its distinctive programming.

Such companies place content creation at their center, and this focus is reflected in their cultures. Content creation functions enjoy generous resources, and customer relationships are built on a high degree of confidence that the company will continue to deliver the kind of content its customers have grown to expect. Their customers, in return, are highly willing to pay, and the company’s content-is-king business model reflects the company’s assurance that superior content will always command audiences who will pay premium prices. Short-term revenues matter less than editorial integrity and brand equity.

Content-led companies tend to follow a first-among-equals organization. While all major functions might report to the CEO, major decision rights reside with content. The content, or production, function plays the lead role and receives the most resources.

The advantages of the content-led model include opportunities for reimagining specialty content (including through an advertising lens) and accelerating development. Content-led companies can also easily embrace incubator- or venture-based models for innovation and new-product development with less fear that the existing organization will try to kill alternative content sources.

However, content-led organizations may miss commercialization opportunities, and maintaining parallel content creation and revenue generation functions and processes can lead to inefficiencies and redundancies, as well as create complexity in approving advertising and branding messages.

Product Led

For product-led organizations, such as Spotify, Amazon.com, and Apple, the medium is the messenger, and how they handle the evolution of digital technologies is the differentiator. Functional excellence is essential in product design and technology. Other functions can be folded into product design, which has the pole position for allocation of resources. These companies are generally not content creators per se: for the most part, the content they deliver is the product of others. There are some notable exceptions, however, such as the Washington Post. Since Amazon CEO Jeff Bezos purchased it in 2013, the Post has focused on the user experience, making large investments in product development and technology to create superior experiences for readers.

Product-led companies need to function effectively in highly competitive parts of the industry (such as streaming services), in which innovation cycles are short and switching costs are low. Customer loyalty is fleeting, audiences embrace change, and consumers move readily to other, newer products that provide a better user experience.

In the tech industry, product-led organizations are common. With their intense focus on product design, most of these companies have a single owner for the user experience, limiting the number of decision makers and voices at the top of the organization. Companies follow a variety of organization models. For younger companies in particular, the community model—a flat organization with loose functional affiliations that work in self-organizing teams—is popular. Employees can assemble groups of people for temporary task forces and projects.

Similar to content-led companies, the mission of product-led companies provides a singular organizational focus—in the latter case, delivering a superior product design and user experience. This focus may cause missed commercialization opportunities and feature creep, and it has the potential to generate decision-making bottlenecks.

Revenue Led

Revenue-led companies, many of which are publically traded, focus on near-term performance. They put the business first. Major decisions are made by a CEO who applies a revenue-generating lens, and the marketing and sales function has an important, sometimes outsize, seat at the table.

The content of many revenue-led companies has been commoditized, the competition is intense, and survival in a disrupted and fast-changing marketplace has become the priority. These companies have developed a culture of monetization, and their audiences are willing to accept the monetization (which in media is primarily through advertising) so long as the content is entertaining or otherwise delivers value.

For these companies, the strong focus on monetization leads to profitability and potentially attractive shareholder returns. Their consumer focus provides a direct link to corporate strategy, clear alignment throughout the organization, and a useful lens for managing the company. Balancing revenue generation with creativity in content generation can create cultural challenges and branding complexities, however.

Hybrid

Some companies pursue a hybrid model that incorporates two or more of the above models in individual business segments or regions or with respect to multiple products. The hybrid approach allows for the pursuit of multiple financial requirements and strategies simultaneously. For example, the operating model of Condé Nast Entertainment, which produces short- and long-form videos and movies, is very different from that of its sister magazine-publishing company. Both are owned by Advance Publications.

Who’s in Charge?

For many media companies—particularly those that lack the inherent clarity of the content- or revenue-led models—making the choices necessary to implement an operational transformation is not easy. But organizations need to know who’s in charge and where important decisions will be made. Resolving whether a company is content, product, or revenue led—or a hybrid—is a prerequisite to determining organizational decision rights.

Resolving whether a company is content, product, or revenue led—or a hybrid—is a prerequisite to determining organizational decision rights.

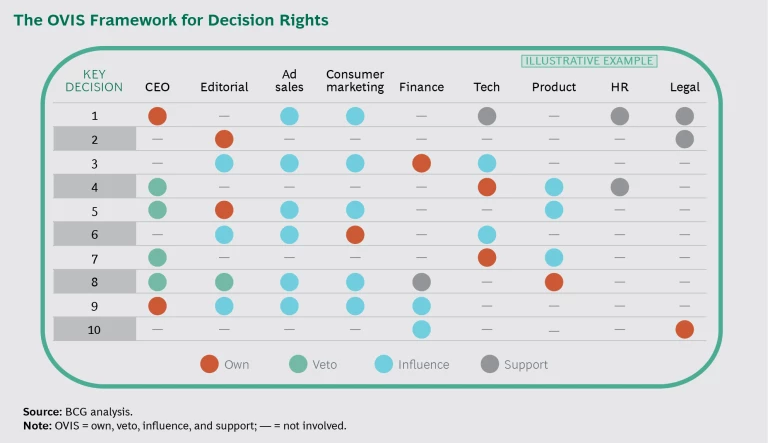

Traditional media companies in particular may find that the product-led model requires too big a leap. It’s a model that can work well if the organization is starting from scratch, but large companies that have operated in the same way for decades typically find that they are not culturally ready for the historically separate and distinct content and revenue functions to collaborate on an equal footing in service of a media product. Roles need to be clear and transparent at all levels of the organization. The various decision rights—own, veto, influence, and support, or OVIS—must be determined for each function. (See the exhibit.)

There will be winners and losers: functions previously considered leaders may, in fact, serve other functions; and functions previously thought to play supporting roles, may become, with the CEO’s anointment, sole decision makers. Absent the difficult decisions to clarify roles and responsibilities, the swirling lack of clarity will continue to plague companies making the digital transition.

Companies that make the tough choices will inevitably experience a period of adjustment and even internal turmoil. But they will be positioning themselves to move forward as speedier, nimbler, and more efficient digital organizations. Others will find themselves stalled in a state of transformation purgatory, arguing incessantly over who’s in charge.