Businesses compete in a world that is growing ever more complex. Disruptive technologies emerge with increasing frequency. Customers’ needs and demands change at breakneck speed. New competitors are always entering the fray.

In their attempts to reduce uncertainty and reestablish control amid this new complexity, companies tend to introduce new reports, new rules, and new processes. Such reactions, however, simply translate external complexity into internal “complicatedness”—the counterproductive proliferation of cumbersome structures, processes, and systems. Complicatedness hinders productivity by creating a work environment that leaves employees disengaged and unmotivated. To be successful in today’s complex and fast-changing world, companies must be highly agile and flexible—able to identify opportunities and make informed decisions quickly in order to exploit those opportunities. Those companies that are able to hone that agility in the face of increasing external complexity will emerge with a clear competitive advantage.

Few companies, however, possess these capabilities. In our discussions with business leaders, we frequently hear about companies that wrestle with a host of internal challenges, including slow decision-making processes, endless meetings, disengaged employees, and increasing costs. And it’s not only senior management that recognizes company shortcomings: employees deep in the organization tell us about their frustrations with meetings that are overcrowded with attendees who have no clearly relevant role, too many initiatives going on in parallel, little recognition from supervisors for results achieved, lack of clarity regarding decision rights, and an inability to get things done quickly.

But while management and other employees are obviously well aware of their company’s flaws, too often they are unable to remedy them. They either refrain from trying to tackle the big problems, or they attempt to address them, only to have the effort fail or even be counterproductive. Many such disappointments stem from actions that, on the surface at least, are reasonable. Management instinctively takes aim at the problems with targeted, direct, and seemingly decisive measures, creating new structures, rules, reports, KPIs, and committees. In many cases, such measures ignore the underlying root causes and ultimately impose even more complicatedness.

Working with numerous clients, each of which started with varying degrees of complicatedness, we have learned that all companies can effectively fight complicatedness and can successfully simplify in a smart way. The key is to understand the link between performance problems and employee behaviors and then determine which elements of the complex, intertwined organization dynamics drive these behaviors. We follow four steps—starting with the identification of the key performance problems and culminating in the design and implementation of solutions. And while this approach demands commitment and energy—as well as a new perspective on what drives company performance—the payoff far exceeds the effort and resources expended.

The Challenge of Complicatedness

Challenges related to complicatedness are deeply entrenched in many large organizations across all regions and industries. But if so many people at all levels are aware of these issues, why are companies unable to fix them?

On the basis of our observation of organizations in numerous industries around the world, we believe that failure is typically the result of one, or several, of a number of (perceived or real) causes:

- The problems and the underlying root causes are difficult to identify and, for the most part, unique to each company. There is almost never a single silver-bullet solution, and implementing standard best practices does not solve the problems.

- The problems appear too big or too “slippery” to tackle. Common refrains: “We would need an entirely different culture to do that” and “Once the external environment changes, things will work out again.”

- The problems are hard to measure, and, therefore, it’s difficult to make the business case to tackle them. The cost of time wasted in unproductive meetings, for example, is much harder to quantify than the cost of physical waste piling up next to a machine.

- Responsibilities for a given problem are divided among various parties and silos, and no one feels compelled to take ownership of the problem. This is particularly emphasized if the problem has in the past proved hard to resolve.

When internal complicatedness is not addressed, tangible value is destroyed. This can be reflected in increasing costs, slow and poor decision making, low employee engagement, dissatisfied customers, and declining business results.

The Power of Simplicity

To successfully address complicatedness, companies need to start by recognizing the principles that form the foundation of BCG’s approach to simplification, or

- Performance is a result of what people do (behaviors). A company’s performance is ultimately driven by employee and customer behaviors. These include the behaviors of leaders (for example, how they lead, whom they promote or make company heroes, what they measure, and what they talk about in meetings) and employees (for example, how they interact, what they do and do not do, and how readily they share information).

- Behaviors of people are driven by rational reactions to their context. People do what they do because it is the logical solution given the context in which they work. Therefore, if a company wants to improve performance, it has to make the desired behaviors rational. Behaviors are observable: they are what people actually do, day in and day out. Behaviors—not a discussion of what people are not (but maybe should be) doing—should be the focus. If it is possible to articulate what motivates people, what they aim for, the means they have to achieve their goals, and what is in their way, it is also possible to understand what causes their behaviors. Behaviors can, therefore, be influenced by smart adjustments to the company environment—the “context”—to make the desired choices the logical ones.

Context includes, for example, the company’s organization structures, processes, reward systems, roles, and career paths. The overall dynamics created by that context and the behaviors they encourage are what we call the system at work. Once a company has developed an understanding of the system at work and clarifies what is really happening and why, it can take steps to modify the system at work and develop desired behaviors. With simplification, the “special sauce” is not what—for example, processes and roles—the company changes. Rather, the real magic is in the new, deep understanding of the behaviors created by the context—for example, those processes and roles—and the interventions that can combine to build a system at work that makes the desired behaviors logical.

Companies that successfully combat complicatedness find that the rewards are significant. One large industrial company used Smart Simplicity to streamline its R&D operations and increase cooperation with suppliers, resulting in a $400 million boost to revenues and an 11% reduction in the time required to get new products to market. And, over the course of four years, a large European bank that—after ten years of failed efforts—embraced simplification amid an increasingly competitive business environment was able to strip $250 million from its costs.

The Problem with Ignoring the System at Work

Classically, companies attack problems by jumping right in and quickly crafting solutions on the basis of accumulated experience and judgment. In many cases, this proves to be the right approach, since many day-to-day problems are relatively straightforward and do not require extensive scrutiny.

Most such quick solutions can be classified into two broad categories:

- The hard approach involves the installation of a structural element that is meant to fix, or at least control, the problem. It includes, for example, the addition of a KPI or a new department to ensure transparency or enhance a specific capability.

- The soft approach is a solution that aims to target behaviors directly. One such solution involves team-building activities aimed at improving capabilities or cooperation.

Today’s business environment and organizations, however, are so complex that, in many cases, these approaches either fail to deliver the desired effects or make things worse. The hard approach, for example, addresses a problem by adding structures such as new KPIs, new dashboards, new processes, and new roles that don’t alter behaviors but typically do increase complicatedness. The soft approach, in turn, can leave people frustrated: in many cases, the organization context blocks even the best-intentioned efforts to put into practice new concepts or ideas derived at sessions such as offsite meetings or trainings.

Viewed objectively, the hard and soft approaches fall short for a simple reason: in most cases, there is no single root cause that is easily fixable. Many of the big internal problems companies face are deeply rooted in the complex, intertwined dynamics of a large organization. In general, the simple challenges—those that lend themselves to quick solutions—have already been addressed. What remain, and really hurt companies, are the deeply rooted problems. For example, a common problem is the lack of cooperation across business units. But real cooperation requires making tough tradeoffs that cannot be addressed effectively by taking the hard approach, the soft approach, or both.

Such problems are not intractable, however. The solution lies in gaining a thorough understanding of the system at work. With that knowledge, a company can design a combination of interventions that address the root causes and modify the system in a way that instills and supports the desired behaviors. This is easier said than done, of course.

Unearthing the System at Work

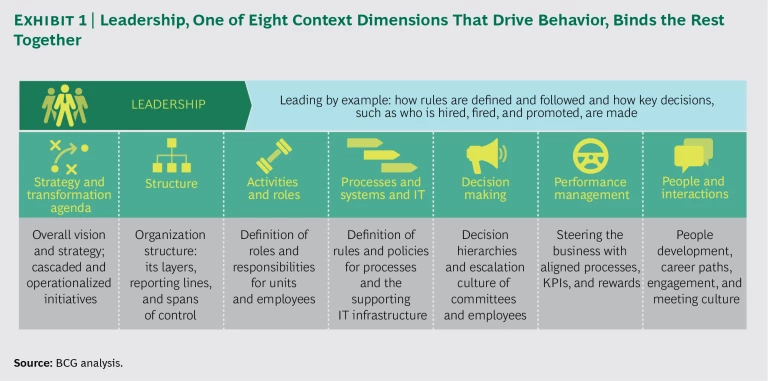

To understand and adjust a company’s system at work, we have grouped the context-defining elements into eight dimensions that the first, leadership, binds together. (See Exhibit 1.)

We use these eight context dimensions as diagnostic lenses through which we can analyze and better understand the current system at work and the state of complicatedness in an organization. The results lay the analytical foundation for socio-organizational interviews with employees to determine how the combination of these dimensions drives behaviors.

A critical feature of our approach is its recognition of leadership. Leadership is a powerful factor, and it has both direct and indirect impact on the other seven context dimensions. Leaders exert strong influence on each of the context dimensions, including how rules are defined and followed and how key decisions—for example, who gets hired, fired, and promoted—are made. At the same time, how well management leads by example and communicates—both verbally and nonverbally—significantly defines the system at work. As a result, we attach particular importance to understanding how leaders are affected by—and how they affect—the system at work.

Once we have established the necessary understanding of the organization’s system at work, we address the problem. This involves modifying the system at work by adjusting the context dimensions to create the desired behaviors.

Fixing the System at Work to Make the Solution Stick

With a solid understanding of the drivers of behavior, companies can implement targeted changes to the context—and the system at work—making desired behaviors rational for employees. Those solutions are sustainable because they address the specific root causes of behaviors. (See the sidebar “Putting Smart Simplicity into Practice.”)

PUTTING SMART SIMPLICITY INTO PRACTICE

The power of Smart Simplicity is most easily understood by studying its impact in the real world. Consider the case of a financial services company we worked with recently. The CEO was frustrated by the company’s failure to execute important initiatives and expedite decision making. In particular, he observed that midlevel managers were not productive and, in many cases, seemed to be preventing initiatives from moving forward. After studying the symptoms for some time, he realized that the issue was the decision-making process, which involved too many layers of the organization before a senior manager could finally decide what should happen. Indeed, a detailed analysis by the HR department showed that on average, each manager had only five direct reports. That seemed easy to fix.

However, attempts to solve the problem, including the creation of an organization design unit to expand spans of control, had little impact. In fact, although spans of control did improve after each initiative, they reverted to old levels within two years. At the same time, the company found that the average length of time to implement company-wide initiatives had doubled, leading to widespread frustration.

Instead of using the standard tools employed to delayer an organization, a team from BCG developed an understanding of the system at work. The root cause of the shrinking spans of control was surprising. Still, it was quite logical from a manager’s perspective. Senior managers at certain levels of the organization were restricted in their ability to reward deserving staff. There were restraints on awarding bonuses, assigning project leadership roles, exercising decision rights over investments, and hiring and firing personnel. In response, senior managers found other ways to reward high-performing individuals. One route was to jump on topics loosely related to their area of responsibility and create small units or departments to work on them. Taking that approach, management had a way to promote a deserving staff member to a role that included a higher base salary, an assistant, a car, and a better office.

From the perspective of managers and their employees, this was, no doubt, an effective means of reward. But it came at a cost to the company as a whole. As multiple senior managers created departments focused on a single topic, it became unclear who was ultimately responsible for related concerns, and the number of units that needed to align on particular topics grew at an astonishing pace. As a result, initiatives basically became deadlocked. And in the face of the inevitable inactivity, managers had little incentive to help others succeed. If, after all, no one was successful, everyone still looked relatively good. No surprise then that managers often blocked initiatives for which they had no direct responsibility. In fact, they grew quite comfortable not having to make any significant decisions.

The root cause of the company’s problems, however, was deeper than a flawed system for rewarding employees. BCG’s analysis of the company’s system at work revealed the underlying driver of the dysfunction: lack of clarity on responsibilities among senior executives serving on the board of directors. Absent effective direction from the board, managers at lower levels of the company determined the topics on which they would focus and created organizations around their priorities.

Once these underlying dynamics were fully understood and accepted, the BCG team worked with the company to implement three interventions. One, the board’s responsibilities were specified, with senior executives agreeing on what their respective organizations would—and would not—be responsible for. On the basis of these responsibilities, the executives defined the responsibilities and accountabilities of their direct reports and their teams. Two, managers were given ways to reward employees without promoting them. Three, traditional delayering methods were applied to create a leaner organization with broader spans of control.

One year after the implementation, initiatives were moving well and spans of control were still high. The CEO noted an improvement in the speed of the decision-making process and the quality of decisions, as well a focus on fewer, but more successful, initiatives. The fix, which had altered behavior, was permanent.

As companies are designing these solutions, management must remember that challenges almost never have a single root cause that can be overcome with a silver-bullet intervention. Problems are nearly always deeply rooted in various interlinked elements of the system at work and can, therefore, be solved only by combining several interventions.

Complicatedness often leads to a lack of cooperation among business units or divisions. This was a major problem for a global machining company with approximately 20,000 employees and $5 billion in sales as it embarked on an ambitious transformation to drive growth and innovation. Revenues and profits were growing steadily. But taking the view that good is sometimes not good enough, especially for a company that aims to be a leader in its market, management made an assessment of what would be required to achieve top-tier performance. The results sparked the creation of a program to bolster sales growth and cut costs.

Resisting quick fixes, company leaders took a hard look at their operating model. The organization had become complicated, with weak cooperation among business segments in both sales and engineering and duplication of work in business segments and headquarters. Employees, who were frustrated by the bureaucratic burden of complex structures and processes, focused almost exclusively on executing well within their particular unit, refraining from cooperating across silos. Company leaders determined that it was time to simplify the organization, get rid of noncore activities, and make it clear that cooperation would be the winning behavior.

We worked with the company to define target behaviors at key points of important processes and then defined the system at work that would drive those desired behaviors. With that understanding, we determined the details of “getting there” using a mix of classical interventions (such as reorganizing the company, harmonizing the setup and processes in sales organizations, and centralizing support and engineering functions), as well as interventions driven by the Smart Simplicity approach. These measures included establishing joint targets and KPIs among company locations and business units and introducing a new role: regional business heads would act as integrators, facilitating collaboration within and among regions.

The interventions were defined and applied layer by layer in a cascading approach. Each layer defined the context of the next layer, creating an ecosystem of cooperation, growth, and efficiency. The results of the interventions were quickly apparent in the form of faster decision making and better collaboration and focus on critical priorities among teams throughout the company. This laid the foundation for the harmonization of processes and ultimately led to a significant reduction in head count.

Eighteen months later, the company had reduced its staff by about 10% and improved the EBITDA margin by 2 percentage points. This improvement was mainly the result of instilling a clearer market focus and eliminating duplication of effort that had been directly related to a lack of cooperation. In a shrinking market, the company was able to boost order intake to record levels. And it became clear that employees felt energized by the changes: employee satisfaction increased across the organization, more than 90% of workers noting a positive impact on the operations of the business.

Four Steps to Simplification

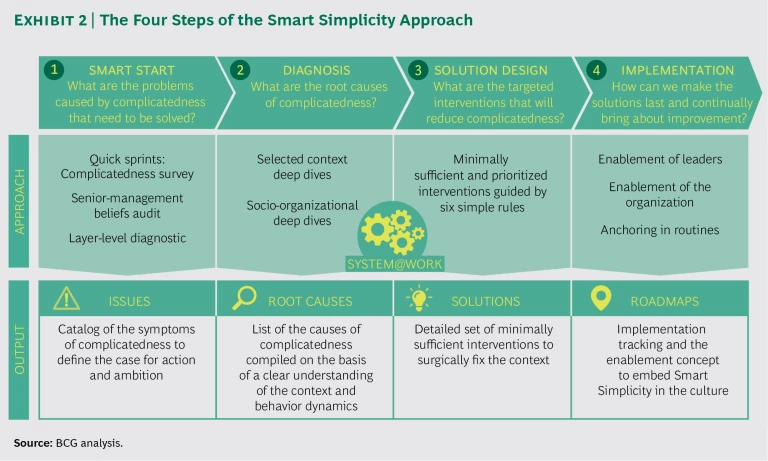

Understanding what drives simplicity is one thing—making it a reality is another. BCG has developed and deployed a four-step approach to simplification. (See Exhibit 2.)

Smart Start. The first step is the identification of the performance issues and the symptoms of complicatedness. A company should not simplify itself only for the sake of simplifying. Simplification is for companies that aim to tackle concrete performance gaps currently caused by complicatedness. The performance issues need to be measurable, and the benefit of addressing the problems should be clear, quantifiable, and worth the energy expended.

In this step, performance concerns—for example, a slow pace of innovation and the loss of market share—are linked to obvious symptoms of complicatedness. This step typically includes a “complicatedness assessment,” which examines the eight context dimensions to identify the symptoms and level of complicatedness, as well as benchmarking against other organizations to establish a baseline of the system at work in the company. In the end, senior managers must reach agreement on the answer to the key question: What are the issues or problems caused by complicatedness that we need to solve?

Diagnosis. This step focuses on achieving a clear understanding of what is causing the performance issues, through in-depth analysis of behavior (what people are doing today) and the context (why they do what they do). The goal is to determine precisely the root causes of complicatedness.

This is generally achieved by defining five to ten use cases, for example, the procurement process that illustrates poor alignment among finance, engineering, and manufacturing. Each use case needs to be clearly linked to a specific problem area or process. Taken together, the use cases should encompass most of the identified performance gaps. In discovering what drives the behaviors of individuals in particular roles in these use cases, we get a good sense of the context changes required.

An analysis of behaviors is done through socio-organizational interviews with the key stakeholders. Furthermore, a context diagnostic is conducted in order to understand the link between context and behavior. These two analyses should provide a rock-solid understanding of the root causes of the performance issues. That insight will establish a concrete rationale for the identified interventions—changes designed specifically to adjust the context in order to remedy the performance issues.

Solution Design. This step focuses on changing the context to make desired behaviors rational. The central question at this point is, What targeted interventions will address the root causes of the performance issues and thereby eliminate complicatedness? This determination is based on the necessary context adjustments that are identified through analysis of the five to ten use cases and the understanding of the required target behavior for each use case. Since interventions are designed for concrete use cases, they are very specific. For example, one adjustment may be to change the performance review process to make behavior X logical for employee Y in a specific situation. Such targeted adjustments have greater and longer-lasting impact than changes made on the basis of industry best practices.

BCG has outlined six simple rules for ensuring minimally sufficient solutions, the critical context changes that make it rational for employees to behave in the desired way. (See the sidebar “Six Simple Rules.”) The rules serve as a kind of quality filter that allows companies to double-check that they have made the right adjustments to the context dimensions, and this, in turn, ensures that the desired behavior changes will be permanent.

SIX SIMPLE RULES

Six simple—and smart—rules help companies make adjustments to the context in a way that ensures that the desired behaviors become logical in key situations.

Understand what your people really do. Management must understand the system at work. Decisions focused on change should be made with input from three to five key internal stake-holders.

Reinforce integrators. It is critical to fully utilize individual employees and groups that work effectively across organization boundaries. To achieve this, the company should assign clear product and process ownership to middle managers and employees. And employees with frequent client interactions, such as those who work the complaint desk, should be em-powered.

Increase the total quantity of power. Companies should look for ways to encourage people to take more initiative, without undermining the power of others in the organization. To achieve this, companies can require managers to use their judgment in their evaluation of their people and can give the managers the authority to mobilize their employees. In addition, rather than forcing employees to comply with an endless number of rules, management should empower them to use their judgment.

Increase reciprocity. Give-and-take leads to cooperation. To encourage cooperation, companies should make certain that employees do not operate in isolation. One way to do this is to ensure that no unit has control over all the resources it needs. And to make cooperation indispensable, the company must clearly define the ways that various roles are jointly accountable for certain goals and outcomes.

Extend the shadow of the future. In many cases, it is difficult to hold someone accountable for a decision whose impact will not be felt for years. Companies should, therefore, give teams end-to-end responsibility for processes and the customer experience. To keep employees from job-hopping, management can stipulate that certain roles be held for a minimum period of time.

Reward those who cooperate. To drive cooperation, companies can link KPIs, compensation, and career progression to both individual and team performance. And it is critical to reward people for asking for and offering help.

Implementation. The fourth step focuses on implementing the solutions and ensuring that they are sustainable and can be improved continually over time. This involves prioritizing solutions and creating an implementation roadmap. An activist project management office (PMO) with clear authority to drive the process, challenge proposed solutions, and make decisions on tradeoffs is a key factor in this phase. To lead its simplification drive, the global machining company described above created such a PMO.

The enablement of company leaders—essentially educating them and giving them the tools for thinking and acting with a Smart Simplicity mindset—is a critical aspect of lasting change. This ensures that the organization will cope with challenges and uncertainty with intelligence and insight. Successful implementation yields improvements in performance, productivity, and employee engagement.

In today’s increasingly complex world, disruptive technologies emerge with accelerating frequency, customer demands change at breakneck speed, and new competitors relentlessly enter the fray. Some companies respond by adding new reports, new rules, and new processes to master complexity. Such responses increase complicatedness, are counterproductive, and hinder performance.

Many companies have the knowledge and skills they need to address the challenges that lead to low performance. But ultimately, they fail because they use the wrong approach. Historical approaches and classical rules of management often fall short in today’s world because they don’t address the fact that performance is driven by what people do—their behaviors—and that people behave in their self-interest and, thus, rationally, given the situation or context. To improve performance, companies have to make the desired behaviors rational.

This is a difficult journey. Changing behaviors is not about putting culture slogans on paper, nor is it about offsite discussions on norms and values or initiatives that make people feel better but fail to yield concrete results. To change the system at work, a company must determine which behaviors are desired and then alter the organization’s context in such a way that these behaviors are rational responses. Using this approach, management can deliver lasting improvement in performance.