Governments must deliver more to their citizens—and do so more efficiently and effectively than ever before. But a surprisingly large number of public sector organizations are hobbled by poor performance at one critical layer of management: frontline leadership.

Again and again, we find that frontline leaders are the key to delivering breakout performance. (See How Frontline Leaders Can Deliver Breakout Performance, BCG Focus, November 2016.) These are the people who serve one or two layers above frontline employees and directly supervise as much as 80% of the overall workforce. They include the manager of a small group of researchers at a government agency, the head doctor or head nurse in a public hospital, the principal in a public school system.

Frontline leaders have an outsize influence on public sector performance—but only 20% to 30% of a typical organization’s leadership development budget targets them.

Public sector organizations looking to ensure accountability, boost productivity, and deliver superior outcomes must change their approach to identifying and developing frontline leaders.

Leaders Adrift

Frontline leaders typically join the management ranks either through long tenure with the organization or because they’ve proven themselves to be effective individual contributors. Neither of these characteristics is a strong indicator of superior management skills, however, and that’s the root of the problem. The most experienced researcher at a government agency or a world-class surgeon at a public hospital may excel at “doing,” but that often doesn’t translate into managing or leading. Nevertheless, it happens all the time; once promoted, these individuals are put in a position where they become the primary face of leadership for the majority of the workforce.

Moreover, most frontline leaders receive little support in their new roles and may be unclear about what’s expected of them as managers. Public sector organizations in particular often have limited budgets for training, and what little there is goes to the most senior people in the organization. In the rare cases where training is offered to frontline managers, it is typically focused on very high level knowledge (leadership principles, for example) and is not designed to prepare leaders for the daily challenges they will face on the job.

As a result, many frontline managers stagnate. Bogged down in administrative work, stuck in meetings, or pulled into the latest crisis, they have little time available to strategize, innovate, or coach employees for performance—though these latter activities would deliver far more value to the organization than the administrative work.

The Urgent Need for Change Agents

Rapid changes in the domestic and international landscape have multiplied the challenges facing public sector organizations. While citizens’ demands for greater transparency and simplicity are growing and the digital revolution is reshaping the public sector, the resources allocated to public sector organizations are flat or declining. Several obstacles make it difficult for organizations to adapt to this turbulent, budget-constrained environment:

- Complex, Difficult-to-Change Bureaucracy. In the private sector, organizations can restructure to become more efficient. That’s not as easy to do in the public sector. The public sector is heavily layered, and it’s difficult (if not impossible) to restructure owing to legal restrictions, regulations, agreements, and other constraints. While some restrictions, such as public procurement and recruitment, are necessary in the public sector, others are no longer useful and lead to undue complexity and bureaucratic burden.

- Flat, Tight Budgets. With budget decisions frequently coming from many levels above, public sector leaders often have minimal discretion over how to allocate funds and few strategic options to catalyze large-scale change.

- Uncertainty in Top Management. Many senior leaders are politically appointed, with a high turnover rate. For example, in the US federal government the average tenure of a Senate-confirmed political appointee is less than 20 months—and steadily declining. With so much turnover, leaders may focus more on short-term initiatives, with staff taking a wait-it-out approach to reform. Other countries have minimal turnover in top management, but that can create a different problem: “lifers” who take a comfortable approach and accomplish little over the course of their tenure.

- Lack of Urgency. In the private sector, competition pushes companies to change, grow, and adapt quickly to new pressures in the marketplace. This kind of pressure exists less frequently in the public sector.

The employees who are best positioned to address these challenges—though not necessarily best equipped to do so—are frontline leaders. They exist deep in the bureaucratic layers of every public sector organization. These potential change agents run core activities and directly affect interactions with the public. They have a tremendous impact on employees’ productivity, engagement, and attrition—and on improved outcomes for citizens.

Given the importance of frontline leaders, it is essential that public sector organizations focus on the best ways to attract, develop, and retain top talent in these positions.

Developing Effective Frontline Leaders

More training isn’t the answer—even for organizations that have the funds for it. Organizations need to move away from “training” and instead embed development into frontline managers’ everyday work routines. Rather than offering broad-based, conceptual training, organizations need to identify specific priorities for these leaders and offer real-world tools and solutions that can be incorporated into managers’ daily and weekly routines.

Our experience working with clients suggests that an effective frontline leadership development program involves three steps.

Recognize What Sets Top Performers Apart

For frontline leaders to become more effective, they need to focus on two or three changes that will have the biggest impact on their performance.

Learn what’s working. To make meaningful changes, frontline leaders must recognize what the top performers are doing differently from their less successful counterparts. This happens best through observation. Are they holding more meetings with their teams, or perhaps just using time in meetings differently? Are they actively fostering a culture of trust? By observing best practices, frontline leaders can learn what works and incorporate these practices into their routine. (See “Frontline Leaders Drive Change at a Multilateral Organization.”)

FRONTLINE LEADERS DRIVE CHANGE AT A MULTILATERAL ORGANIZATION

FRONTLINE LEADERS DRIVE CHANGE AT A MULTILATERAL ORGANIZATION

At a global multilateral institution headquartered in the US, senior executives developed a new set of strategic priorities that required a comprehensive organizational transformation. But the organization had a reputation for being bureaucratic and slow moving, with a disempowered workforce.

To create cultural change at the grassroots level, senior leaders focused on empowering their frontline leaders first. The organization’s frontline leaders were asked to shadow top performers to observe and identify what “good” looks like. Through observation and interviews, frontline leaders identified three specific things that top performers were doing differently. First, they developed employees’ capabilities by offering regular structured and unstructured feedback. Second, they promoted a culture of trust by providing full visibility into managerial decisions and by recognizing employee achievements. Third, they delegated downward by creating “sandboxes” where employees could work independently to build new capabilities.

After codifying these behaviors, frontline leaders throughout the organization were able to integrate these best practices into their daily routines and strengthen the efficacy and culture of their teams.

Learn what’s not working. Another way to improve the performance of frontline leaders is to track the stress points in their work lives. Is too much time being spent on paperwork? In nonessential meetings? Doing the team’s job rather than leading?

By breaking down the workday and tracking leaders’ routines, it becomes obvious where time is being squandered on low-value activities. With this data in hand, senior leaders can spot negative trends, identify root causes, and determine if this is an isolated problem or a more widespread organizational issue. If it’s the latter, the organization can put measures in place to help frontline managers deal with these stress points. Furthermore, frontline leaders should be given ample opportunities to share with senior executives the challenges they’re facing as they implement reform. Even potentially effective leaders can struggle if they aren’t supported by the right processes and tools. So, while it’s important to evaluate what’s working and not working in people’s daily routines, it’s also important to assess the effectiveness of specific processes and tools that frontline leaders rely upon every day.

Focus on Tangible Solutions

To initiate meaningful change in the public sector, frontline leaders don’t need to be steeped in policy handbooks. Rather, they should be empowered with actionable frameworks and tools that enable them to experiment, identify routines in the workday that are critical to performance, and make adjustments to improve.

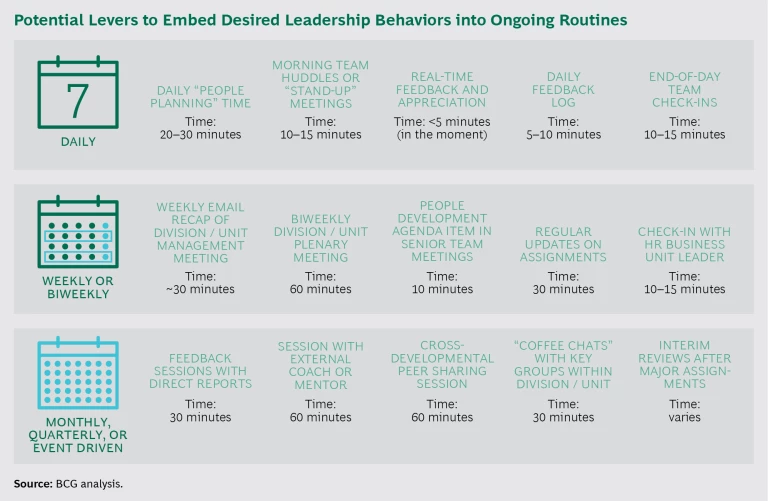

Establish new routines. Armed with knowledge about what works and what doesn’t, frontline leaders can begin to incorporate new routines and rhythms into their days. These new routines will likely include a variety of recurring activities, including regular team check-ins, coaching and mentoring (with peer groups, one-on-one mentors, and subject matter experts, for example), job programs and rotations, and structured and unstructured feedback. (See the exhibit.) The best frontline leaders can serve as trainers and coaches to their peers, helping them incorporate best practices into the daily routine.

Design for scale. Because organizations employ so many frontline leaders, it’s imperative that new routines be scalable across the organization. To make this happen, organizations should start with an initial pilot in a single business unit or department, then test and learn what works, and next roll it out to other areas of the organization. Where possible, digital tools can be used to implement changes. Mobile apps, for example, can help frontline leaders manage their time and solicit feedback on their own performance. (See “Frontline Leaders Transform Education in India.”)

FRONTLINE LEADERS TRANSFORM EDUCATION IN INDIA

FRONTLINE LEADERS TRANSFORM EDUCATION IN INDIA

For years, India has focused on improving access to schools. Haryana, a state in northern India, has been successful in expanding accessibility to match the national average, but academic quality has not been adequately addressed. To boost quality, Haryana officials implemented a comprehensive and transformative roadmap for change—but with 15,000 schools and more than 2 million students, it was an extremely daunting undertaking.

The state’s frontline leaders (that is, school principals) were fundamental to the program’s success. They worked directly with school system leaders to help develop the roadmap for change. Once the roadmap was developed, all 15,000 school principals took part in change management workshops that equipped them to lead the transformation in their own schools. Though they didn’t have access to state-of-the-art technology, they used creative, straightforward techniques—such as communicating with teachers through SMS group chats—to disseminate best practices and monitor performance. Reward and recognition programs were also put in place to motivate the principals to stick with the transformation agenda.

By incorporating change from the inside out, Haryana schools have measurably improved learning and engagement. Once-declining literacy and numeracy rates have turned around within just two years of program implementation—and Haryana is showing the fastest rate of educational improvement in India.

Make The Changes Stick

Because frontline leaders work so closely with employees, they are perfectly situated to support long-term, bottom-up change within the organization—but they also need the right incentives and culture to support their efforts.

Provide the right incentives. Organizations can use formal or informal rewards and recognition to reinforce new behaviors and bolster morale, but incentives need to be fully aligned with organizational objectives. For example, if the top management at a public hospital communicates that high-quality care should be the staff’s number-one priority but rewards budget compliance rather than customer satisfaction, the incentive is not aligned to the stated objective.

Build a strong leadership culture. In the public sector, it’s important to build a leadership development program that starts outward from there. Frontline leaders should always be an integral part of any reform effort, given their field experience and strategic leadership role. Top-down orders aren’t particularly effective in the public sector, and when frontline leaders are brought in at the early stages of reform efforts, they are well positioned to help create buy-in.

Frontline leaders should also serve as a kind of “human hub” for both internal and external stakeholders. A school principal, for example, not only benefits from establishing a close relationship with internal units, like human resources, but also can take advantage of public services (by partnering with social and health services to support students, for instance) and external organizations (by partnering with a community theater program to provide new enrichment opportunities for students).

To make changes stick, frontline leaders should work closely with the management layer that exists just above them. When empowered by strong relationships at this level, frontline leaders can seek out the support they need to establish new rhythms and routines. (See “Small Changes in Routine Spark Big Changes in Leadership.”)

SMALL CHANGES IN ROUTINE SPARK BIG CHANGES IN LEADERSHIP

SMALL CHANGES IN ROUTINE SPARK BIG CHANGES IN LEADERSHIP

A public sector agency in the Middle East wanted to strengthen its leadership ranks—from frontline managers to senior executives—to improve communication and collaboration within the organization.

To achieve this goal, the agency created a Leadership Academy, grouping small cohorts of leaders (frontline leaders, senior executives, and others) who would attend workshops and seminars together over an eight-month period in a highly tailored development program. These interactive sessions addressed real problems that leaders were facing in their functions. Importantly, these problem-solving sessions enabled simple changes in regular routines that had a big impact on the team’s effectiveness. By training managers up and down the line, each cohort was empowered to reinforce the others’ new routines on a day-to-day basis.

In the words of one employee: “The Leadership Academy has improved communication so much. We are changing from a ‘memo’ culture to a ‘just pick up the phone’ culture.”

Measure impact. To understand where and how changes are taking root, it’s important to understand what frontline leaders are doing differently than they have in the past—and how this is contributing to positive change. Are frontline leaders coaching employees more? How do their teams feel about them? Has productivity improved? Based on these metrics, coupled with knowledge gathered from qualitative interviews and pulse checks, organizations can find ways to continuously improve.

Public sector institutions all have very different objectives—educating our children, healing the sick, sending astronauts into space—and they all have extraordinary potential to change citizens’ lives for the better. By taking the time to understand what makes some frontline leaders excel while others underperform, organizations can better equip public servants to deliver breakout performance. This, in turn, builds a pipeline of internal talent that will eventually rise up to become the public sector leaders of tomorrow.