The Art of Planning, which examines the ten principles driving best practices in corporate planning, is part of a publication series by BCG on CFO excellence. The Art of Performance Management looks at the critical components of a best-in-class performance management system and operating model. The Art of Risk Management discusses the ten principles that should govern an approach to risk management.

Historically, corporate planning has been relatively straightforward for company leaders: assess the business environment; agree on objectives and the means for reaching them within the context of a relatively stable corporate strategy; set target revenues, costs, and time frames; and move on. Today, however, companies face new challenges that complicate the process and necessitate dynamic and very different planning strategies. In this new era of heightened economic volatility , planning becomes more, rather than less, relevant and critical.

Since businesses face more aggressive competition than ever before and have to assume increasing risk, they need to prioritize their deployment of resources even more carefully and govern their wide-ranging global activities more diligently. Smart planning has never been as important as it is today.

In this Focus, we delve into the changes and challenges that have altered the context in which companies must now undertake their planning. We break down the impact of external issues stemming from an increasingly complex—and less predictable—global economy. We also investigate company-specific internal problems, which include basic planning missteps, pseudoaccuracy, and poor time management—shortcomings whose root causes often run deep. These issues become even more important in an uncertain environment because they amplify the impact of external challenges.

How can companies cope with these external and internal changes and challenges? BCG has worked with clients to help them actively prepare for today’s altered environment. Here, we examine best practices at several of these companies and reveal ten key principles that have improved effectiveness and efficiency in their planning processes. As companies incorporate more of these principles and related practices into their playbooks, they will become stronger, more flexible, and more dynamic—ready for a new world of business.

External Changes: A New Reality

In the so-called old reality of just a few years ago, a company’s market leadership position was defendable, and its size and position in the marketplace were a clear determinant of its ongoing performance. Markets were equally attractive to all the businesses participating in a market, and a company’s strategy development and planning were grounded in a mostly reliable, steady, and predictable context. But the global financial crisis has both accelerated and amplified fundamental, long-term changes—leading to a new reality and leaving many companies unprepared. World markets have become rife with volatility, large-scale default risks, and refinancing uncertainties—an atmosphere that has led to shifts in consumer behavior and increased risks in regulation and policy. The effects of globalization, the fiercer fight for resources, and the emergence of what we call a two-speed world—that is, a world divided into fast-growing emerging markets and struggling developed ones experiencing slow or no growth—were all felt more acutely as a

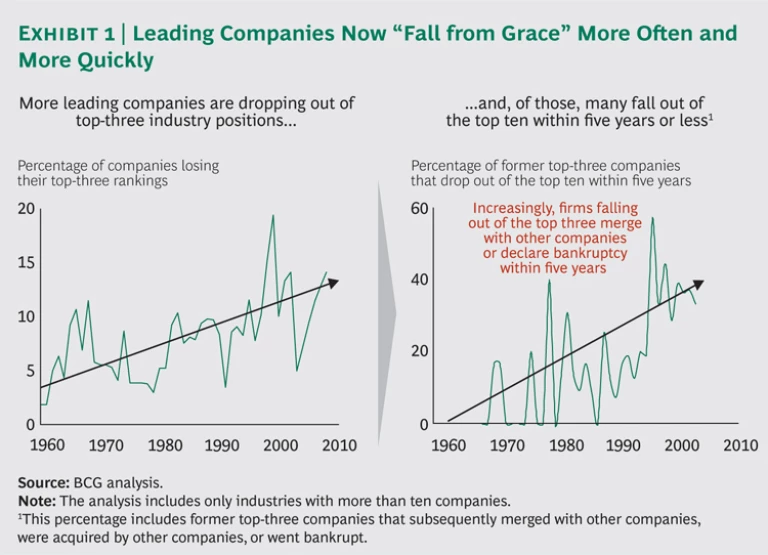

The new reality is a globalized marketplace in which information is ubiquitous and, at times, overwhelming. Unpredictable forces frequently emerge, such as influential social movements or increased roles for local and national governments. And in this altered landscape, market leadership is far less sustainable. Higher percentages of companies are dropping out of top-three industry positions than before, and those that do are now more apt to slip from top-ten rankings within five years of their initial fall—often because they declare bankruptcy or are acquired by or merge with other companies. (See Exhibit 1.) Success has become less stable and less directly correlated with the size or legacy of a business. In addition, there is a more dramatic disparity in earnings between top and bottom performers, proving that the “cost of being wrong” has increased and the attractiveness of a marketplace differs greatly among the players competing in it.

Corporations around the world are feeling the heat from a variety of external sources. Competition is intense and heterogeneous, with a continuous string of new upstart players jumping into the ring. New technologies add to the pressures on corporations as well. The lack of stability and predictability in this new reality make it that much harder for organizations to flex their muscles, and they now have to learn to be as agile and

Internal Strife: How Companies Hobble Themselves

The new reality that has taken hold in the world today brings with it specific requirements and a new learning curve. Internal, company-specific issues contribute to planning difficulties as well, especially because they leave organizations ill-prepared to cope with the external situation. Often, these company-level shortcomings have root causes that run deep, and making adjustments will take commitment. The following are examples of internal issues that limit successful planning at many companies.

Strained Resources and Employees. In many organizations, the degree of effort and expense put into planning is so out of line with the value added that it becomes a wasteful exercise. Often, these companies remain wedded to traditional, full-blown planning that consumes the attention of many employees for a large part of the year. Some have even upgraded the degree of detail and the number of dimensions covered by planning, requiring elaborate breakdowns by legal entity, country, division, product, customer type, and factory.

The volatility of the current market further complicates detailed planning and requires an even greater time commitment, preventing involved managers and employees from taking part in critical business activities. In addition, many companies become trapped: the complicating factors of planning prompt them to start the process early in the year, but this early planning sometimes results in outdated values even before the new year has started—eventually leading to excessive iterations and reviews. Such efforts actually give companies less flexibility in a global environment that demands more flexibility than ever.

Process Inefficiencies. Many employees say that even when initial planning seems to occur efficiently, they find their figures challenged several times as they move through the process, which causes parallel planning and redundancies. Requiring heavy detail early on is unproductive, leading to unnecessary iterations and number crunching. And all that detail keeps a company stiff just when a shaky economy requires adaptability in working through effective scenario planning.

Unreliable, Low-Quality Data. Despite the significant resources and attention to detail dedicated to planning, companies often end up with plans that are based on inconsistent and sometimes poor-quality data. The results may appear thorough and consistent when it comes to financials, but many organizations have become expert at achieving pseudoaccuracy, and the link with strategic planning is frequently missing. Plans often need to be revised and modified several times a year, especially in turbulent economic times. This typically leads to even more inconsistencies between different partial plans, including cost plans, revenue plans, factory plans, and plans for full-time equivalents (FTEs).

Company Culture and Management Style. A company’s culture is frequently at the heart of mismanaged planning, with management often rewarding the wrong behavior. Because financial incentives are still frequently tied to the achievement of short-term plans, employees can feel pressured to negotiate financial goals and to sandbag. Consequently, planning begins to feel like a bazaar instead of the organized, top-down process it should be. Employees may be motivated to reach goals precisely but never to exceed them, since doing so would mean having to reach even higher goals the following year. This “plan low so you can perform high” approach by employees, in turn, fosters a mindset among top management of mistrusting data and asking almost by default for still-higher performance. Overall, this type of planning leads to budgets and targets that reflect internal negotiation and corporate networking skills rather than true business opportunities.

We argue that given today’s volatile environment, the overall focus for planning must move away from precise forecasting and toward more strategic, top-down ambition-setting that is validated with bottom-up business insight. This approach should be tied to contingency plans in case the targets cannot be met—and complemented by more frequent short-term forecasts of key metrics. However, embracing unpredictability and encouraging entrepreneurship within reasonable limits entails a significant shift in the management culture of many large corporations.

Embracing Change: Ten Principles Driving Best Practices

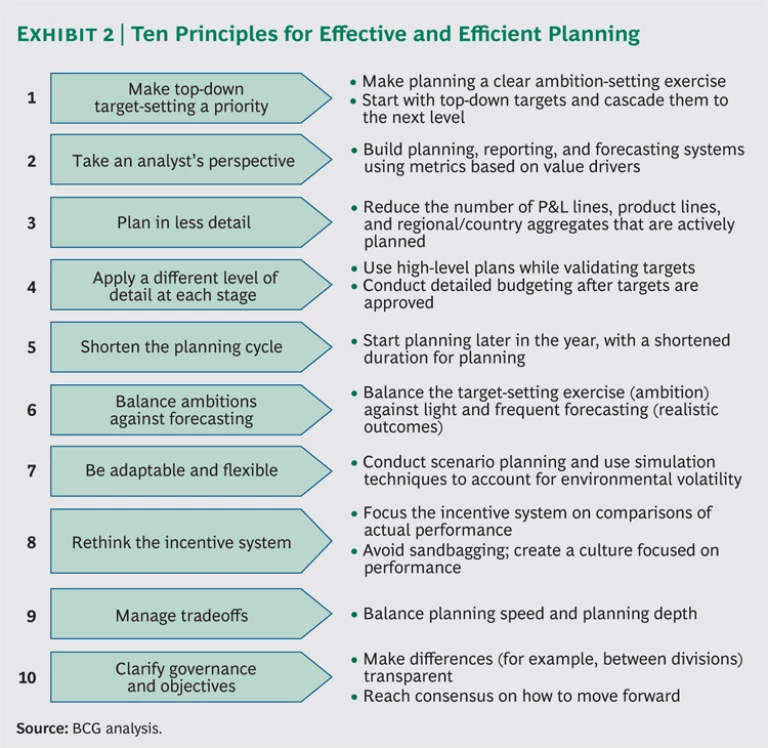

Many organizations have already succeeded in changing their planning processes to become more effective and efficient in today’s new reality. We have helped clients across several industries make this transition, a process that has revealed the key principles that drive the best practices for success. Not every exemplary company applies all of the principles, and the approach to implementation varies in each instance. How the best practices are applied depends on the preferences of key decision makers and on corporate characteristics such as business dynamics, company culture, and legacy. Still, these ten principles can serve as an overall guide to improving an inefficient planning system. (See Exhibit 2.)

Principle 1: Make Top-Down Target-Setting a Priority. The degree to which an organization is comfortable with top-down targets and target scenarios is driven largely by its deep-seated company culture as well as its legacy incentive systems. Today, that culture must be shaken up, and target setting must become a top-management responsibility. Setting ambitions (or targets) using a top-down approach will ensure that goals cascade to all the levels within the organization. Goals and investments should be rooted in an effective strategic-planning process that includes a transparent strategic assessment of the respective businesses.

One client we worked with in this area is a fast-moving-consumer-goods (FMCG) organization that has proved effective at implementing a limited set of top-down targets—such as net external revenue, operating income, and cash conversion. Another best-practice example is a global conglomerate that has found success using a top-down approach to create an aggressive target range or “stretch corridor” after asking each business unit to provide one-page answers to five strategic questions. Under this approach, leaders assess the current global market dynamics for a unit and predict the dynamics for the following several years, taking into consideration how the competition could influence those plans. They then must figure out the most effective means for bringing about the desired impact on the current dynamics. These approaches create simple playbooks that do not emphasize the attainment of specific numbers. Rather, they are meant to result in the best performance possible.

This principle is especially important in dealing with the economic crisis. By setting the most ambitious yet achievable targets, management stretches performance and pushes employees while avoiding overtaxing and discouraging people. A full 100-percent achievement of goals is not necessary as long as the company comes close to its target and realizes improvement over the prior year’s performance.

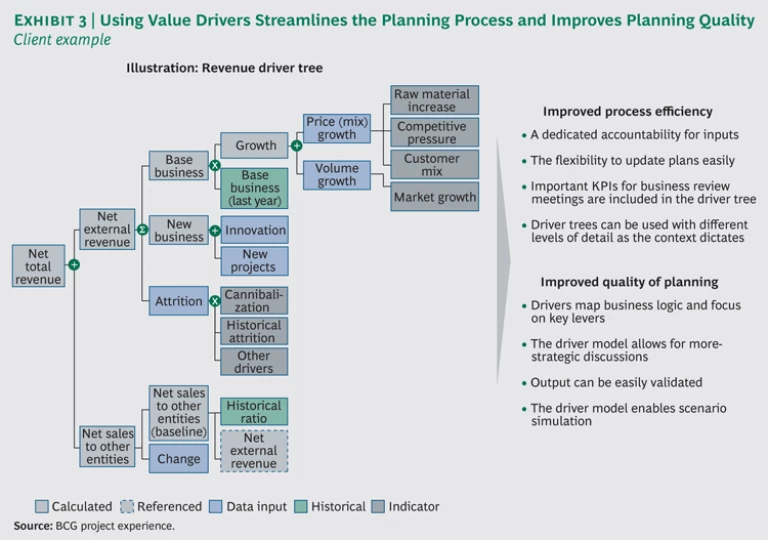

Principle 2: Take an Analyst’s Perspective. Start to de-emphasize absolute values in planning—the detailed financial line items—and become immersed in planning, forecasting, and reporting systems that use metrics tied to value drivers. A driver-based approach allows for a more useful discussion of underlying assumptions and does away with bazaar-like negotiations, or sandbagging. The application of value drivers facilitates the link to strategic planning and fosters strategic discussions and a perspective on total shareholder return. (See Exhibit 3.)

One organization that makes effective use of the analyst’s perspective is a pharmaceutical company that now plans deviations from the previous year only on the basis of underlying business drivers, such as market growth, market share development, the development of the relative price point, and the price index for raw materials. As more companies alter their attitudes toward the details of planning in this way, they can be increasingly flexible in scenario planning, too—a capability that is crucial in meeting the new external challenges.

Principle 3: Plan in Less Detail. Reduce the scope of the planning process by validating fewer planning targets. Less detail makes for greater flexibility, quicker response time, and better simulation capabilities. Some companies are even limiting themselves to considering only the major possible effects—known or predictable factors that will affect future business—and leaving everything else in their forecasts constant.

One BCG client, a global diversified company, has significantly reduced the amount of detail included in the planning activities of each of its business units. Globally, several hundred planning items have been reduced in number by 60 to 70 percent. Again, the fewer details, the simpler—which translates into being faster at adapting and better prepared for competition in a changed world.

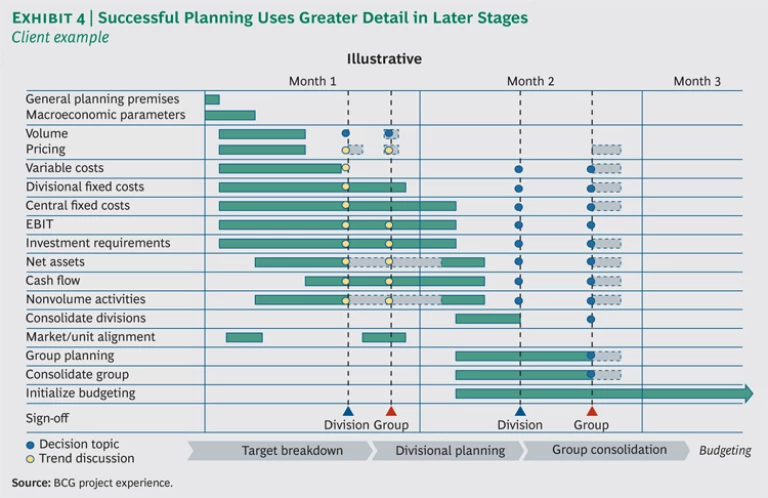

Principle 4: Apply a Different Level of Detail at Each Stage. Spell out the key planning parameters before initiating a full-fledged bottom-up validation of targets. Start detailed budgeting as soon as the targets have been agreed on.

An international consumer-goods company applies this best practice with success. The company now conducts high-level plans while validating planning targets for volume, prices, sales mix, marketing, variable costs, and fixed costs. After targets are approved, the company budgets in greater detail. Another client, an international automotive company, requires clearly distinct levels of detail at each stage of planning, including a benchmark-derived target during strategic planning, a systematic breakdown of strategic targets during operative planning, and a breakdown of targets to cost centers once the high-level targets have been approved. (See Exhibit 4.)

Such strategies make the most sense, considering the current external realities of volatility and change—and the call for simplification in Principle 3 above.

Principle 5: Shorten the Planning Cycle. Start the planning process later in the year and shorten its overall duration. A shorter cycle puts the emphasis on speed and flexibility and results in less overall company coordination, fewer parallel and redundant activities, and less frustration. Furthermore, getting a later start translates into using the most recent information and basing targets on more accurate data. Less detail, greater process discipline, and more effective use of planning tools will help ensure a shorter planning cycle.

We helped one global FMCG company reduce its cycle from 120 days to 60—and a German conglomerate cut its entire cycle from ten months to five, enabling it to begin the planning process in July instead of February. An international automotive company we worked with now starts its operative planning for the following year on September 1. In this new economic environment—with change occurring at a rapid pace—delayed planning is the best strategy.

Principle 6: Balance Ambitions Against Forecasting. Effective planning—and a more realistic outcome—results from striking a balance between the setting of targets (ambitions) and light but frequent forecasting. To make this happen, management has to agree on the desired level of precision—applying a common set of minimal and transparent requirements that are consistent across and within divisions. (For example, companies must insist on a regulated hierarchy of planning objectives that follows the steering logic with a consistent set of line items.) Is it more important to stretch the organization to improve performance, or is the goal to set targets as precisely as possible? Be sure to differentiate between target setting and forecasting.

The key is to focus the mid- to long-term plans and the one-year plan more strongly on ambition setting and to use annual planning for a review of strategies and key business objectives. Detect risks and early deviations from the plans and get input for the short-term optimization of resource deployment such as cash management and short-term liquidity management. Then create a quarterly, or even a monthly, forecast. Here, scenario planning can be a good strategy: look for trends that deviate above and below the plan, and start creating contingency plans early on. When forecasts suggest deviations above plan, think about production and the logistics needed to handle more volume. When deviations below plan are expected, consider countermeasures, such as sales activation and pricing.

Principle 7: Be Adaptable and Flexible. To be prepared for “environmental” or market volatility, stress the importance of scenario planning and simulation techniques and make them integral elements of the planning process. Consider conducting scenario planning at different times

We saw this best practice put to use by a shipping company we worked with. The company developed a new forecasting system based on value drivers to allow route managers to adjust volumes within their areas of responsibility. The new targets are then extrapolated using standard costs.

Principle 8: Rethink the Incentive System. Companies often measure success and award incentives by comparing performance to a forecasted plan—but this approach places too much emphasis on plan delivery and not enough on maximizing performance. Instead, they should calculate incentives using an “actual-to-actual” comparison, which measures how much actual current performance surpasses actual prior performance—in short, real-world results and improvement. This change can help reduce sandbagging by employees and foster a culture focused on performance. An actual-to-actual comparison can better identify where companies are falling short on long-term strategic ambitions than can data on short-term deviations from forecasts.

Alternatively, companies can explore having a base plan as well as a stretch plan; this dual approach requires clear top-down expectations for targets. In the past, planning may have been used as more of a disciplinary tool than a visionary one. Now, it is crucial for management to alter its style and be more willing to accept degrees of uncertainty, which the dual approach allows.

One client, a global industrial supplier, introduced an annual performance bonus based on target achievement and complemented it with multiyear objectives for gains in value creation over actual, rather than planned, levels.

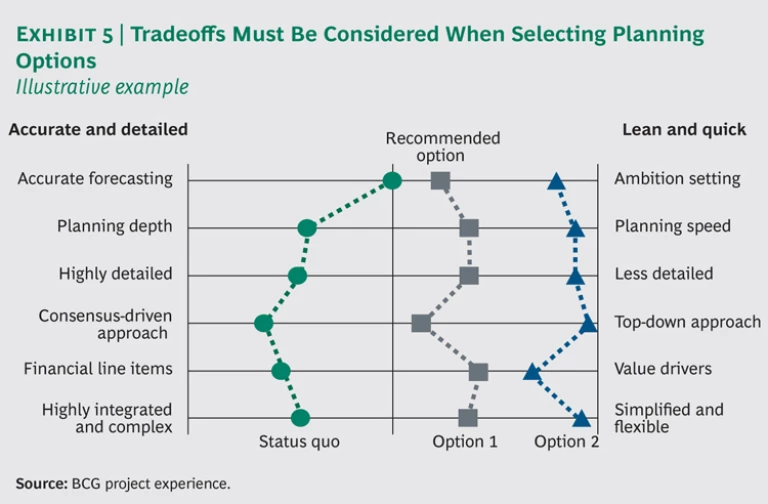

Principle 9: Manage Tradeoffs. In order to make changes to their planning systems, companies must acknowledge the necessary tradeoffs involved. (See Exhibit 5.) For instance, as described in Principle 6, management has to weigh ambition setting against forecasting and agree on the required levels of precision. Business leaders must also balance speed and depth in planning, understanding that to achieve greater speed, some depth will be sacrificed. For effective simulation in planning, data on relevant business drivers—which are not always collected and applied today—have to be included. And to cope with the complexity inherent in simulations today, the number of line items included, or planning depth, must be reduced.

Principle 10: Clarify Governance and Objectives. Planning is a key steering instrument that will influence the overall direction of the business. There might very well be differing opinions within divisions, among divisions, or between the divisions and corporate headquarters about the best direction to take. These differences have to be made transparent, and all relevant stakeholders must reach consensus on the best path forward. For example, they must agree on whether to place greater emphasis on ambition setting or forecasting.

Because shareholders and advisory boards expect external forecasts, companies must ultimately create two plans: a realistic external plan and a more ambitious internal plan. Planning has often been deeply integrated into the reporting logic, and planning and reporting frequently share the same systems and use similar data fields. But integration does not always make sense because both views should be reported separately to best meet planning requirements.

Furthermore, as new planning concepts are put into place, changes in IT tools will be required—an added cost that management must be willing to accept.

Communication and Change Management

Breaking bad habits and mastering the art of planning is about more than the implementation of any or even all of the principles described above. Change has to be balanced with company needs, taking into consideration the business environment and company culture. It’s not just about doing the right things; it’s about doing things right.

There are two components of change. So-called hard change—which includes new systems and processes, control of new process standards, and the avoidance of parallel planning—is indeed important. But just as key is the concept of soft change, which includes communication, the involvement of top management, and decisions about tradeoffs. (Pilot programs are often an effective means of making soft changes in planning succeed.) The best planning requires a combination of both of these components.

A crucial type of soft change involves altering the mindset of the stakeholders. Companies must make sure that their key decision makers accept any planning adjustments before a new approach—the hard changes—can happen effectively. Top-level business managers must be fully on board and believe in the importance and pursuit of the impending changes. If they are not convinced of the value of a new planning approach, it is likely to fail. Change cannot be driven by the finance function; it has to be fully endorsed by the CEO and key leaders, who are willing to embrace change for themselves and in their

In addition, excellent communication is paramount. Change is not easy for any organization and cannot be done on the fly. Decisions have to be made with great care, and the necessary tradeoffs have to be identified and explained so that everyone understands the purpose of the new approach. As the altered planning concept gets under way, business leaders will continue to make important decisions and put a lot of effort into change management.

These soft changes in planning have to be achieved across all levels of the organization. Top-level executives have to comply with certain rules of discipline, such as not requesting further detail beyond the defined level needed for planning. Middle management has to take part in honest discussions of business possibilities without resorting to sandbagging. Collaboration between the business and finance functions is crucial. And all changes have to be explained clearly to line managers, who then must be sure to comply with the new tool requirements, timetables, and mandated levels of detail. If there is open communication among all participants, a revised planning system can be successfully established and embraced.

Rewrite the Rules

The status quo for business is no more. Companies have to participate on a world stage that is more complicated and more unpredictable than ever. At the same time, old habits die hard, and flaws inbred in organizations must be identified and corrected. Rewriting the rules for planning is not easy. But with some companies already leading the way, new best-practice examples are available for everyone else to learn from and follow. With fine-tuned communication, transparent leadership, and a willingness to change their culture, companies can implement effective planning.