When people imagine the cities of the future , they typically envision the urban landscapes of science fiction: gleaming metropolises with flying cars and technology powering everything. In fact, however, the city of the future will rely far more on strategic planning and governance than it will on technology.

To be clear, technology can indeed help solve some of the large and growing challenges of urbanization. By 2030, more than 5 billion people—60% of the 2010 global population—will live in cities. Meeting the needs of these urban residents will put a tremendous strain on municipal governments, and many are rushing to invest in technology, hoping that it will provide a fast and easy solution. The impulse is understandable: technology is advancing rapidly and has transformed many industries. But under the current approach to implementation—a series of short-term decisions—technology is unlikely to achieve its full potential.

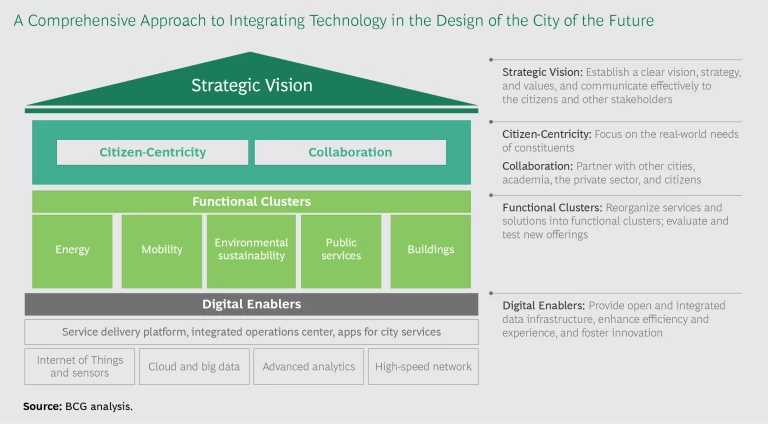

To solve the problems of urbanization and to design livable, sustainable cities of the future, governments need to adopt a far more strategic approach, of which technology is only one part. They need clear upfront analysis to identify the biggest issues that their cities and constituents face, and they need to design collaborative and citizen-centric solutions that use technology to address various functional clusters: energy, mobility, environmental sustainability, public services, and buildings. This is potentially harder and more time-consuming than simply buying software from a vendor. But it is the only way to generate sustainable results.

The city of the future will rely far more on strategic planning and governance that it will on technology.

Urbanization Brings New Challenges

Urbanization will present challenges on a massive scale. About 55% of the world’s population currently lives in cities, according to the UN, and projections call for this number to increase as rural populations shrink. Not all cities are growing at the same pace, however. By 2030, roughly one-sixth of the world’s population will live in just 41 very large cities—each with a population of more than 10 million people. That kind of concentration among populations can create conflicts—and greater urgency for city governments—in three specific areas:

- Economic Competition Among Cities. Large cities often siphon capital and business activity away from smaller cities nearby. And because concentrated populations lead to increased economic opportunities—an effect that becomes self-reinforcing—large cities win and smaller cities nearby lose. New development and infrastructure can sometimes intensify the problem.

In 2008, for example, the Chinese government built a high-speed rail line between Wuhan and Guangzhou, cutting the travel time between the two cities (roughly 600 miles apart) from 11 hours to about 3. Slower trains used to stop at those cities, but the high-speed line did not. As a result, the populations of many of the smaller cities along the route experienced a net decline from 2008 to 2016, while the populations in the cities at either end of the line increased significantly, accruing economic benefits.

- Concentrated Opportunities. According to one estimate, 5% of the world’s cities in 2030 will contribute more than one-fifth of the world’s GDP. This concentration of economic activity can lead to greater income disparities between the populations of large cities and small cities. Even within the limits of any individual city, wealth accumulates at the top, leading to a growing split between the rich and the poor and, in some cases, social instability. In the US, among the five cities with the highest per-capita GDP, four of them— Boston, New York, San Francisco, and Washington, DC—also show the highest gap in incomes. Only Seattle has managed to keep the income disparity down.

- Environmental Challenges. A concentrated population allows for the delivery of more efficient public services, but as cities grow bigger, governments often struggle to meet the needs of larger populations. Currently, about 35% of the world’s urban population faces either inadequate or unaffordable housing. Residents in the 25 largest cities lose an estimated 66 hours per year sitting in traffic jams—and increased traffic leads to increased pollution. Only 10% of the global urban population lives in areas that currently meet World Health Organization standards. The environmental challenges grow as cities expand in size, and the effect is most pronounced in developing economies, where the majority of megacities are located.

In the aggregate, significant complexities for municipal governments are arising in all three areas and creating increased urgency to solve them.

Technology Offers Possible Solutions

To address these challenges, many cities are investing in digital technology, which holds considerable potential to help leaders improve urban planning, foster equitable economic growth, deliver services more efficiently, and use more sustainable resources.

To improve planning, for example, governments can use data infrastructure and analytical tools. A government agency tasked with designing and building a city center cannot do so effectively unless it has accurate information about the projected uses for the site, the number of people who will use it, the types of services those citizens will need, and other critical information.

Technology can also help cities foster more equitable growth. The market for “smart city” technology is growing at 21% per year, to a projected $1.5 trillion by 2022. China is the leading country in absolute terms, spending up to $250 billion in 2017, though growth rates in the US and Western Europe are higher. A cloud-based data center in Busan, South Korea, will create 30,000 jobs alone.

What’s more, technology can help cities use resources more effectively and create healthier urban environments. Digital solutions are helping cities generate reductions of 15% to 30% in CO2 emissions, energy and water consumption, traffic congestion, and crime. They also help cities deliver services far more efficiently. In Australia, for example, approximately 80% of the population is expected to access government services through digital channels by 2020.

For these reasons, city governments are spending significantly on technology. In India, the government plans to invest more than $1.5 billion in technology initiatives across 100 cities. China launched pilot projects in more than 500 cities in 2017 alone. Canada plans to build 100 smart buildings in the next three years and reduce energy consumption in existing buildings by 17%.

Limitations on Technology

However, technology often comes with its own set of issues, which can hinder efforts to harness its full benefits. For example, digitization projects, such as government initiatives to offer e-services to its citizens, often have many stakeholders, each with their own priorities and interests, and planners struggle to meet the requirements of all the parties. In addition, project designers sometimes have a poor understanding of the core users of a new solution—or the problems those users are trying to solve—and they don’t apply a structured approach to business model design. As a result, when projects finally go online, adoption rates are limited.

What’s more, some cities invest in a series of individual solutions and applications that are not compatible with one another. Systems and databases are not integrated, often due to competition among vendors, but the cost of replacing those items is so high that cities cannot afford to change them.

Even projects that are successful at the pilot stage can run into problems when they are rolled out across the broader city government. Critical hurdles often include adapting the organizational structure and building the right internal capabilities to meet the requirements of the new system.

Financial constraints are compounding all these problems. The cost of urban construction in many cities is growing faster than GDP and taking up a larger share of city revenues. Government debt is growing worldwide. In the long term, technology investments that are smartly designed and implemented can generate an attractive return on investment—for example, by spurring economic growth and allowing governments to deliver services more efficiently. But that is little help for governments that simply do not have the capital to make the required upfront investment. (See “ The $75 Trillion Opportunity in Public Assets ,” BCG article, October 2018.)

A Comprehensive Approach to Building the City of the Future

Because of these challenges, governments cannot turn to technology for an immediate fix. Instead, they need to understand how technology can address human needs. In other words, they need a comprehensive approach to urban planning—one that incorporates technology to facilitate broader solutions.

This approach has several aspects. (See the exhibit.)

First, each city needs to develop a strategic vision for the future that takes into consideration several factors: its unique circumstances; the biggest issues it is likely to face in terms of services, resources, population growth, and other factors; and how it plans to solve those issues—not in terms of months or years but decades. (See the sidebar “Beijing Creates a Strategic Vision to Develop Two Urban Districts.”)

Beijing Creates a Strategic Vision to Develop Two Urban Districts

Beijing Creates a Strategic Vision to Develop Two Urban Districts

Beijing has created a strategic plan to develop two nearby districts as part of a broader plan to build a world-class city of the future.

The first is Yanqing, a relatively undeveloped district that has primarily served as a green space outside of Beijing, with little infrastructure or industry. As Beijing grows, it needs to develop the Yanqing district while still preserving its environmental advantages. The goal is to create an ecologically healthy city that is a destination for sports and wellness activities. (Among other priorities, Beijing is hosting the Winter Olympics in 2022, and many of the venues will be in Yanqing.) The strategic plan also calls for improved infrastructure and livable communities in Yanqing that can attract commuters who work in nearby districts. And an innovation cluster will include mixed-use spaces that draw high-tech companies and businesses in creative industries, such as marketing.

The second district is Tongzhou. Currently a bedroom community with a large population of people who commute to the commercial districts of Beijing, Tongzhou has limited land for development. The strategic plan calls for turning Tongzhou into a new type of city center that can be a hub for increased economic activity while still avoiding some of the congestion and other problems of other parts of Beijing (a largely unplanned city). The vision calls for some technology, such as an open-access data platform and underlying infrastructure, but only as part of a much broader vision.

By developing a strategic plan to revitalize two very distinct districts in Beijing—one suburban and the other urban—municipal planners are creating a new mode of development that is very deliberately planned and can serve as a model for subsequent measures across the entire Beijing region.

The strategic vision needs to incorporate two core principles that guide future development: citizen-centricity and collaboration. Regarding the first, governments need to think in terms of their constituents, asking themselves, Who are the groups that the new plan is supposed to serve, and what are their needs? For the second core principle, governments must collaborate directly with its citizens, so that they are involved in designing and testing solutions, which will lead to greater adoption rates when those solutions are ultimately rolled out. (See the sidebar “Stockholm Focuses on Citizens and Partnerships in Developing Its Strategic Plan.”)

Stockholm Focuses on Citizens and Partnerships in Developing Its Strategic Plan

Stockholm Focuses on Citizens and Partnerships in Developing Its Strategic Plan

Several years ago, the Stockholm government developed a strategic plan known as Vision 2040, which included such aspects as sustainable development, equal access to education, reasonable housing prices, and environmental sustainability. Technology is incorporated as a means for achieving this vision, but it is not the ultimate end in itself.

Adopting a citizen-centric approach, the city identified specific demographic groups and interviewed people in those groups to better understand the problems they faced. It also compared its services for those groups with international baselines and then identified specific ways to improve the delivery of services. Citizens could even suggest new services they wanted to see.

To collaborate, the city partnered with academic institutions and companies, including Ericsson. Stockholm is leading a project with seven other European cities in which they all develop and test specific solutions and share best practices. On the technology front, the city government created a digitization lab so startups can develop and test their ideas in an urban setting. And it partnered with six other public organizations to increase the number of commercial digital applications for elderly people living at home.

As Stockholm considers new services, it prioritizes them by cost and demand among residents; notably, some of the highest-priority projects do not require any new investment in technology. And once new services are in place, the government establishes clear KPIs in terms of time, cost savings, citizen satisfaction, and return on investment, so it can accurately gauge their performance against expectations.

The third layer of a comprehensive solution consists of functional clusters—the actual groups of services and solutions that governments offer: energy, mobility, environmental sustainability, public services, and buildings. Municipal governments need to identify and prioritize improvements in these clusters on the basis of the most urgent needs.

Finally, city planners can turn to technology to build the actual digital infrastructure—the network, applications, sensors, analytics packages, and other tools—that can help enable the solutions identified in previous steps. Critically, any technology needs to be well designed and analyzed in terms of its costs and potential benefits. The design and testing of new services is also important prior to implementation, particularly for those with a safety aspect, such as transportation. And in some cases, technology itself can be used to test potential offerings, through simulations and other tools. (See the sidebar “Boston Tests a New Technology to Reduce Traffic.”)

Boston Tests a New Technology to Reduce Traffic

Boston Tests a New Technology to Reduce Traffic

In Boston, the government wanted to test several ideas, including the use of autonomous vehicles, to reduce the city’s notorious traffic congestion downtown. The city built a traffic simulation of the condensed downtown area with its infrastructure elements: 53 traffic signals, more than 70 miles of streets, and 12 bus routes. The model factored in characteristics associated with driving behaviors, such as travel speeds and the typical distance between vehicles, and took into account various types of vehicles—cars, buses, and taxis—as well as pedestrians.

Within this area, the city simulated the impact of a shift to autonomous vehicles in different configurations: individually owned cars, taxis, ride-sharing taxis, and buses. By evaluating various scenarios, the city determined that the greatest gains would come from ride-sharing taxis, which would lead to an 85% drop in CO2 emissions, a 54% drop in collisions, and an 87% drop in demand for parking spaces. On the basis of these findings, Boston’s government can start crafting policies that create incentives for this kind of traffic in the future, as the self-driving taxis gradually become available. The result will be transportation policies that are far more effective than those based on gut instinct.

In sum, technology holds tremendous promise to help municipal governments create the smart city of the future, but only if they get smart about the implementation process. Rather than simply buying individual solutions, governments need to develop a more comprehensive strategy that puts citizens first and relies on collaboration. In this way, governments can generate the highest possible return on their investments and build a long-term plan that will serve their needs regardless of which technologies are in or out of vogue.