How do governments fare when it comes to strategic planning and execution ? Consider a recent session BCG conducted with a group of government leaders. To kick off the discussion, we asked for a show of hands: Who among you knows exactly what your agency’s priorities are? A few raised their hands. We then asked, Who among you believes that your agency’s strategic-planning process has had a real impact on your work? Again, just a few. Our final question: How many of you think that your agency can—and must—do better in this area? To that, everyone raised a hand.

Smart planning and sustained execution are needed to anticipate and navigate the increasing complexity and challenges facing government leaders around the world. Governments must make the best use of limited resources and mitigate the risks of economic and political turbulence. Despite these imperatives, public-sector agencies commonly fail to value strategy, and they rarely excel at strategic planning and execution. The result: government leaders struggle to change their organization’s behavior and to drive progress toward the most important policy outcomes.

The key to upping government’s game on this front is to understand what prevents effective strategic planning and execution and then to attack those challenges head on. On the basis of its more than 50 years of working as a leader in strategy, BCG has developed deep insight into the barriers that confront the private sector and an understanding of how they also challenge the public sector . These hurdles include a planning system that is too focused on bureaucratic processes at the expense of outcomes. In the public sector, such challenges are compounded by the frequent changes in leadership that are tied to election cycles, entrenched hierarchies and regulations, and a culture of risk avoidance.

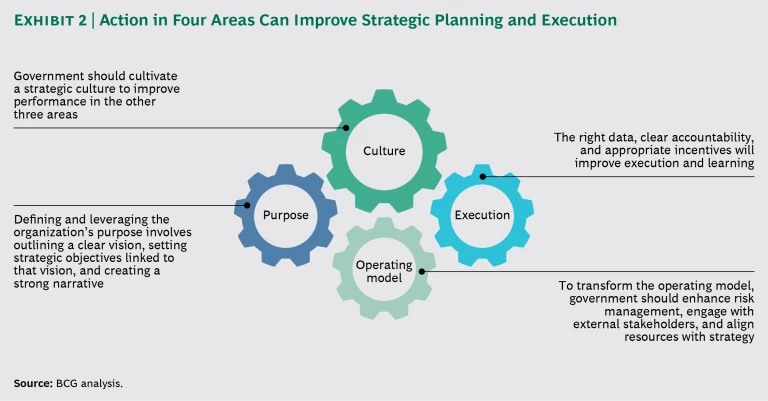

Drawing on 31 interviews with current and former public-sector leaders around the globe, we have identified four steps that governments can take to eliminate these obstacles: promote a strategic culture, leverage the organization’s purpose to catalyze action, transform the operating model, and build a system for execution and learning.

Remaking the strategic-planning process is not about creating the optimal meeting schedule, metrics, or mission statements. It is about building a system that allows agency and department heads to determine priorities, put adequate resources behind those priorities, and then hold people accountable for results. It is about solving real problems. When they achieve this, government leaders find that they are fighting the right battles and delivering lasting value for their citizens.

Government’s Strategic-Planning Imperative

It is through strategic planning and execution that both private- and public-sector organizations develop and implement strategies, whether for corporate growth or for achieving a federal mandate. Through this process, organizations reconcile their responsibilities with their resources and set strategic priorities. When done well, strategic planning and execution can effectively account for and manage the numerous variables that affect their plans and programs and make the important connections within and among stakeholders, allowing them to work in concert toward critical goals. Sustainable and flexible execution of the strategy promotes the likelihood that government will deliver on its promises, improving citizens’ confidence and promoting their trust.

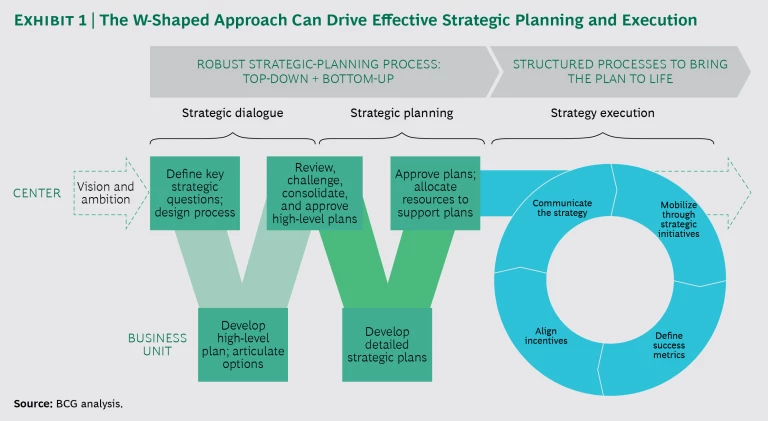

Exhibit 1 illustrates one highly effective approach to strategic planning: the W-shaped model. (See Four Best Practices for Strategic Planning , BCG Focus, April 2016.) This approach starts with leadership’s definition of the organization’s vision and strategic ambition. Next, the division, field unit, or function heads are asked to respond to a series of pointed questions about the organization’s big challenges relative to this vision. Answering these questions, the unit or function heads suggest concepts or proposals for meeting the challenges. On the basis of their subsequent discussion, management selects proposals and assigns the unit or function heads responsibility for developing detailed plans for putting those proposals into action. Management drives execution of the plan, as well as a system for learning and adapting that is based on new information.

Mounting Public-Sector Challenges. The need for this sort of effective strategic-planning and execution process in government is intensifying in the face of four difficult realities.

First, owing to the scale and pace of change, including changes driven by advancing technology, today’s operating environment is more complex than ever before. Case in point: the democratization and proliferation of advanced technologies is upending the way governments manage risks to security and their economies. Second, finding solutions to most public-sector challenges requires the involvement of more stakeholders—in and out of government—than in the past. For example, responding effectively to the risks posed by infectious diseases such as the Zika and Ebola viruses required international collaboration within and across government agencies as well as the private sector. Third, many governments are facing ongoing erosion of public confidence. A 2017 Pew Research Center survey, for example, found that only 18% of Americans trust the national government to do what is right. A 2015 survey by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, meanwhile, found that just 43% of citizens in its member countries trust their government. Fourth, many governments are feeling the squeeze on discretionary spending due to rising deficits, aging populations, and the increasing cost of government services.

Obstacles to Effective Strategic Planning. Amid such challenges, strategic planning becomes more important than ever before. However, in many public and private organizations, such planning is frequently undervalued and poorly done.

Many of the obstacles are common to both government and the private sector. In numerous situations, the process is too bureaucratic, requiring multiple iterations and consuming too much time. It can also be too internally focused, failing to account for external factors or to learn from the experience of other sectors or similar organizations. Furthermore, in all too many cases, strategic planning excludes key stakeholders who are needed both for diagnosing challenges and for delivering outcomes. The failure to involve midlevel managers is particularly problematic because it can mean that the right issues are not elevated to the attention of senior leaders as they set strategy and that there is limited buy-in among the rank and file, weakening execution. Finally, there is a disconnect between the strategy and the incentive structure that is meant to promote follow-through on the strategic plan.

Public-sector organizations are, of course, quite different from private-sector companies. Some challenges seen in the private sector may be magnified in the public sphere while other additional issues that exist in government have no presence in the private sector.

For one thing, government leaders—especially political appointees—generally have a more limited window of time for action than do private-sector leaders. That’s because there is high turnover among government leaders in many countries. In the U.S., for example, not only does a considerable majority of the federal government’s most senior political leaders turn over every four to eight years, but the average tenure of a federal government, Senate-confirmed appointee is only 18 to 30 months.

At the same time, although many government leaders have solid policy expertise, a large number have little of the strategy and management expertise that comes from running a large and complex organization. As a result, it’s not unusual for them to delegate responsibility for the strategic-planning process, and they are not always personally invested in execution. This lack of engagement at the top filters down, leading to marginally engaged staff members who are not optimally committed to developing and implementing the organization’s strategy.

Finally, many government organizations don’t perceive risk as private-sector companies do. Public-sector organizations can often be focused on short-term outcomes and compliance with rules and regulations rather than on long-term strategic results. Consequently, creating a strategy that can be adapted in the face of changing environments or new information is difficult.

Building a Strategic-Planning Process That Delivers Impact

To improve their strategic-planning and execution track record, government leaders should focus on steps that leverage four critical areas: culture, purpose, operating model, and execution. (See Exhibit 2.) Steps taken in these areas affect all stages of strategic planning—and can enhance the entire process. Of the four, culture is the most critical. It shapes and is shaped by the other three major levers for change. Changing an organization’s culture will unlock opportunity in the other three areas and help embed change in the organization.

Promote a Strategic Culture

Certainly, there are pockets of robust strategic planning in government, particularly within the defense sector : it is ingrained in the military profession. But either the culture of too many public-sector organizations does not embrace the value of strategic planning or the organizations’ leaders aren’t committed to that process.

To ensure a successful culture shift, the head of the agency or office must take a leading role in strategic planning, middle management must be involved from the start, and the risk-averse mindset inherent in government organizations must be addressed.

“Strategy is ultimately the top leader’s responsibility,” according to one former senior government official. “You can’t delegate responsibility for leading change.” Public-sector leaders must personally drive the effort to set strategic priorities, build buy-in, align resources, communicate the strategy consistently, and hold people accountable for executing the plan. And they should make it clear to everyone in the organization that the unit responsible for strategic planning has a clear mandate from the top.

To draw midlevel management into the strategic-planning process from the start, senior management must identify key staff throughout the organization who have responsibility for implementing policies and programs and bring them into the process through cross-functional teams. In addition, leaders should link the day-to-day work of frontline staffers to the strategy by highlighting ways that their roles and responsibilities—and the strategic-planning system itself—can help eliminate the obstacles to achieving important objectives and directly contribute to solving citizens’ real-world problems. Such steps will develop strategic thinking in personnel who are likely to be the next generation of leadership. And just as important, it will build buy-in for the strategy, making successful execution more likely.

The former head of a major operational directorate within a large government tax authority told us, “If a team is closely involved in developing the strategy, they will feel ownership of it. If they feel ownership, then they will want to make it work.”

For the head of one large government diplomatic organization, ensuring commitment to the strategy among the rank and file was critical for delivering results. She initiated and personally led a strategic-planning process when she took the helm of the organization a few years ago and involved managers from across the organization in the effort. In addition, goals were designed to drive agency-wide cooperation across various functional and regional silos. “This created a clear sense of where we were going, why, and the role each group played in achieving our goals,” she reported.

The conservative mindset that some government organizations cultivate in employees can be a serious impediment to execution of the strategy. It’s important to find ways to reward and protect—not punish—those who take reasonable risks and achieve less than positive results.

The head of a large transportation department understood that risk aversion could seriously undermine the progress of an extensive infrastructure project that the department was managing. The staff knew that rather than confine traffic to one lane during the many months of construction, the most cost-effective way to manage one element of the project would be to completely shut down traffic for several weeks. The head of the department knew that shutting down all traffic would generate short-term public outcry, but he was willing to take that risk. He understood the long-term public benefit and cost-saving opportunity that could be achieved in expediting the project, and he made it clear to his staff that he would own the decision should public backlash be directed at any of them.

Leverage the Organization’s Purpose

A critical element in effective strategic planning is a clear sense of purpose, which consists of an organization’s timeless reason for being—its mission—and the strategic goals for fulfilling this mission within a set period of time. Strategic planning and execution allow organizations to deliver on that purpose by setting priorities, aligning resources, and mobilizing and measuring action.

The following three actions help overcome the barriers to effective strategic planning and execution that stem from the organization’s overall sense of purpose:

- Reinforce the core mission of the organization. In addition to reinforcing the core mission, which is generally rooted in law, the leaders must articulate a compelling vision for advancing the mission over a three- to five-year period. This will provide critical direction and energy for the organization and ensure that all staff members understand where the organization is moving.

- Set clear strategic priorities to achieve the vision. This step may seem obvious, but it is rarely easy. “Deciding among top priorities is a challenge,” a former senior advisor in the U.S. executive branch told us. “Not everything can be a priority. You need ruthless prioritization.” Staff will play a key role in this area, helping to frame the inherent tensions and tradeoffs among these priorities.

- Communicate the strategy throughout the organization. Organization leaders must make strategy come alive by providing their staff a consistently vivid strategic narrative that is relevant to their day-to-day activities. This story should be related energetically throughout the organization: the top leaders communicate the strategy to their direct reports, who then communicate it to the people they manage, and so on. The cascading narrative should show workers how their actions, driven by the new strategy, directly contribute to improving the organization’s performance. Such clarity can go a long way toward improving the odds of successful execution of the strategy.

Consistent messaging was a powerful tool for mobilizing staff behind a large government defense agency’s new strategy. To help drive change, a variety of carefully drafted messages were developed to communicate the strategy, including a short “bumper sticker” message, a three-minute elevator pitch, a series of videos from top leaders, and detailed documents and presentations. One senior leader recalled that the head of the agency “joked that the strategy bumper sticker message would end up on his tombstone.” Still, consistent communication was critical. “Absent that kind of commitment to messaging of the strategy,” she noted, “it is difficult to overcome the cultural resistance to change.”

Transform the Operating Model

Typically, the public-sector operating model—the governance, structure, and processes of a government agency—is hierarchical, rigid, and not adaptable to changing circumstances. Action in three areas can eliminate those impediments and, in so doing, enable a more effective and efficient operating model:

- Communication and Engagement with External Stakeholders. Government leaders should create a clear process for working with, for example, appropriators, authorizers, budgeting agencies, the office of the president or prime minister, citizens, and industry in order to secure the necessary resources and support for the strategic objectives.

- Integration of Risk Management in the Strategic-Planning Process. Strategic planning and risk management must be integrated so that the organization can anticipate and prepare for the full spectrum of potential problems and opportunities that could arise during execution. In many cases, the primary risks relate to insufficient statutory authority, resource constraints, and weak or unwilling external partners. And effective risk management requires looking at the organization’s entire interrelated portfolio of programs, rather than addressing only risks that are within silos or that are perceived as external to the organization.

- Adapting Processes to Support the Strategy. New programs, policies, and the ways that their success is tracked and that resources are allocated should be directly linked to the organization’s strategic objectives. The use of agile teams—groups whose members are from functions throughout the organization and that are designed for rapid experimentation and adjustment—can provide powerful support in the design and development of these programs and policies. (See “ Taking Agile Way Beyond Software ,” BCG article, July 2017.) Such teams can generate quick insight on which initiatives are working and which are not. In addition, what success will look like for each strategic objective should be clear, with specific performance goals, indicators, and milestones identified for assessing progress. Furthermore, leaders must ensure that the disposition of resources and talent and the decision-making process are driven by the organization’s strategic priorities. The head of the large diplomatic organization mentioned previously says that more often than not, this is the exception in government. In many cases, she noted, “the strategy is not viewed as something that helps us get resources. There’s very little correlation between the strategy and budget requests.”

Leaders within the large defense organization described previously not only created multiple ways to communicate the strategy but also built a process that ensured that strategic priorities were supported with the necessary resources. During the budgeting process, one military department cut back on orders for equipment that was needed to support a crucial strategic objective. The aim was to trim purchases in order to invest in modernizing other conventional capabilities. Armed with a clear understanding of the priorities, senior defense organization leadership directed the department to fund strategically important equipment while allowing the department to determine how to offset the costs of other, less critical programs.

Develop a System for Execution and Learning

Agencies that lack critical tools and data that can be used to measure progress cannot adjust course on the basis of new information. In addition, when strategy is not integrated into the day-to-day actions of frontline staff, employees can focus too much on programs that are not relevant to the organization’s strategic priorities.

Doing an effective job of executing and adjusting the strategy hinges on three elements: the right data, a system that values accountability and aligns incentives, and the ability to adapt where necessary. The involvement and commitment of frontline managers is critical to success in all three areas.

The data required includes not only upfront information about what works in terms of programs and initiatives—data that can drive the initial strategic-planning process—but also timely and action-promoting data during the execution phase. Such information can come from both internal and external sources. Internal data may be the result of monthly strategy “pulse checks” with staff, quarterly or annual strategic reviews with senior managers, and evaluations of specific programs. External data can and—in many cases—should include information on the impact of certain programs in the real world. For the data to make a difference, it must be available, reliable, and timely. A senior executive in a large finance and tax agency told us that it’s important to “measure what matters—and movement will happen on things you measure.”

The second element—accountability and incentives—is critical to successful execution. Leaders should hold regular evidence-based progress reviews with key managers, including officials who have direct oversight of programs that support each strategic objective. The sessions should focus on performance data for each program and allow in-depth discussions that include suggestions related to improving performance and mitigating risk. These sessions must be held more frequently and cover more detail than the annual or quarterly strategic reviews that many government departments and agencies already conduct. At the same time, the organization should create clear and valued incentives, including formal and informal awards and recognition for those who adopt new behaviors and contribute most to achieving objectives.

The most effective government organizations understand that without accountability and the right incentives, even the best strategic plan will likely never become reality. One large agency responsible for managing much of the government’s real estate holdings held biweekly meetings at which staff reported progress on strategic priorities. According to the agency administrator, that “repeatable rhythm” of reporting kept the team focused on those priorities. A public-housing-and-finance organization, meanwhile, tied management’s performance evaluations to the accomplishments of the agency’s strategic objectives. This required identifying the right metrics for tracking progress against the objectives and instituting a credible and timely review process that integrated that information.

The third element—the ability to monitor performance in a way that helps the organization adapt—can result in two types of adjustments. First, data on the progress of key strategic objectives can help the organization alter the way it is executing its existing strategy. The strategic objectives may not change, but the way in which the organization tries to achieve them may. The second involves revision of the strategy itself. The need for such a shift can become evident only if the organization steps back periodically to assess whether or not things have changed in the overall operating environment. Such analysis may reveal that the assumptions on which the original strategy was based have changed, making it necessary to revisit the strategy.

Government agency and department heads worldwide can confirm that, as public-sector leaders, they are struggling to be successful in a uniquely challenging period. Political upheaval is the norm, and technology continues to alter the ways that society functions.

In such an environment, government institutions must up their game or risk becoming irrelevant to the citizens they serve. Because confidence has slipped and must now be rebuilt, governments will be forced to take a major leap in the ways that they plan and execute strategy. Government leaders must institute a strategic-planning process that identifies the right priorities and drives decision making that supports those priorities. Taking steps in the four areas we’ve outlined—culture, purpose, operating model, and execution—can move governments from endless rounds of planning to delivery of results.