“The leader of the market today may not necessarily be the leader tomorrow.”

—Ma Huateng, Tencent founder and CEO

O

nce upon a time, high-performing businesses could expect to keep succeeding for the foreseeable future. In the mid-20th century, for instance, 77% of industry-leading companies were still on top five years later.

What happened? The business environment has become much more dynamic, which means the requirements for tomorrow’s successful companies will likely be different from those for today’s. Instead of relying on current performance to continue, businesses must now continuously innovate and reinvent themselves.

As companies age and grow, however, reinvention becomes harder: business and organizational models become entrenched, running the day-to-day business requires more focus, and complexity builds up and becomes a barrier to change. As a result, at a time when companies need to explore new options more than ever, many are instead increasingly dependent on legacy business models . In other words, many incumbents are at risk of losing vitality.

Winning the Next Decade Requires Forward-Looking Metrics

As leaders start to plan for the next decade, maintaining vitality—the capacity to explore new opportunities, renew strategy, and grow sustainably—is more important than ever. The competitive landscape of the 2020s will look very different from today’s as powerful trends continue to unfold, including the rise of artificial intelligence, the changing nature of the company-employee relationship, and new balances of economic and geopolitical power.

Traditional ways of measuring business performance do not reflect this new reality. Revenue growth, profitability, and financial returns are all inherently backward-looking, so they tend to promote a focus on optimizing today’s business model instead of envisioning tomorrow’s. To survive and thrive in the next decade, leaders must be able to measure, revive, and sustain their companies’ vitality.

To help fill this gap, we created the Fortune Future 50 index . Developed with Fortune magazine, the index is forward-looking—it is based on the factors that predict future revenue growth, which drives the majority of high performers’ shareholder returns in the long run. It provides a perspective and tool for leaders to assess and manage the vitality of their enterprises. (See "Measuring Vitality from Wide-Ranging Data Sources")

Measuring Vitality from Wide-Ranging Data Sources

Measuring Vitality from Wide-Ranging Data Sources

Our index is based on two equally weighted pillars:

- Future Market Potential. The expectation of future growth from financial markets, defined as the present value of growth options (PVGO). This represents the share of a company’s market capitalization that is not attributable to the earnings power of existing assets and business models.

- Company Capacity. Our assessment of the company’s ability to deliver on this potential. It comprises 17 factors, drawn from a larger group of variables and calibrated against historical data for their ability to predict long-term revenue growth.

The capacity index draws heavily on nonfinancial data sources and modern analytics. For example, we used artificial intelligence algorithms to identify predictive patterns in unstructured text data. From 30,000 SEC filings and annual reports, we used a Long Short-Term Memory neural network (a natural language processing model that incorporates word order and context) to characterize a company’s strategic orientation on three dimensions: long-term orientation, focus on a broader purpose beyond financial performance, and “biological thinking”—the ability to embrace the uncertainty and complexity of business environments and address them with flexibility, adaptation, and mutualism.

The factors that best predict growth are grouped into four areas:

- Strategy. Long-term strategic orientation, commitment to a greater purpose, and biological thinking; clarity of strategy articulation (as assessed from earnings calls); and the company’s governance rating (according to Arabesque, a pioneer in ESG analytics).

- Technology and Investment. Capital expenditures and R&D expenditures (as a percentage of sales, compared with sector averages); growth and digital intensity of a company’s patent portfolio (from a global database of patent filings); and quality of the company’s startup investment portfolio (based on comparison with the best-performing global venture capital funds).

- People. Gender diversity of managers and employees; youth of executives and directors; leadership stability (lack of executive and director turnover); and smaller board size.

- Structure. Age since company founding; size of the company (based on revenue); and growth track record (over prior three years and six months).

Note: Digital intensity is based on the share of patents in the areas of computing and electronic communication.

It is focused on forward-looking considerations such as the following:

- Do we have a sufficient pipeline of “future bets” with high growth potential?

- Does our strategy balance short-term exploitation with long-term exploration?

- Are we developing sufficient capabilities in the technologies that are transforming how businesses work?

- Do we have a culture that promotes cognitive diversity and a competition of ideas?

- Are we willing and able to challenge our incumbent approaches and beliefs?

Where to Find Highly Vital Firms

From this index, we identified outperformers—established companies that have best maintained vitality. We call this group the Future 50.

When we created the first version of the index, last year , it was limited to only US public companies.

This year, we have expanded our analysis to cover corporations around the globe. Our index assesses the vitality of more than 1,000 of the largest global firms (those with at least $10 billion sales or a $20 billion market capitalization).

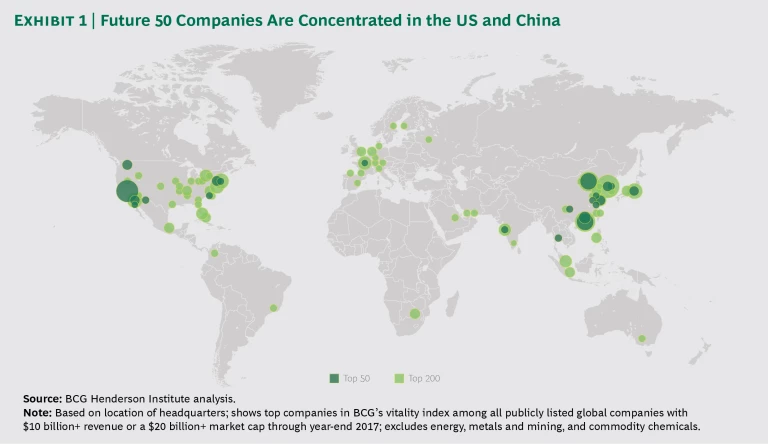

We found that the most vital firms are highly geographically concentrated: 42% of the Future 50 are headquartered in the US, and another 42% are in Greater China. Extending the analysis to the top 200 companies, we find that both regions continue to be overrepresented, though the pattern is not as extreme. (See Exhibit 1.)

Even within these regions, vitality is unequally distributed: the majority of Future 50 companies are based in the two “gold coasts” : China’s east coast and the US’s west coast. These include our number one company overall (California’s Workday) and our number two (Beijing’s Weibo).

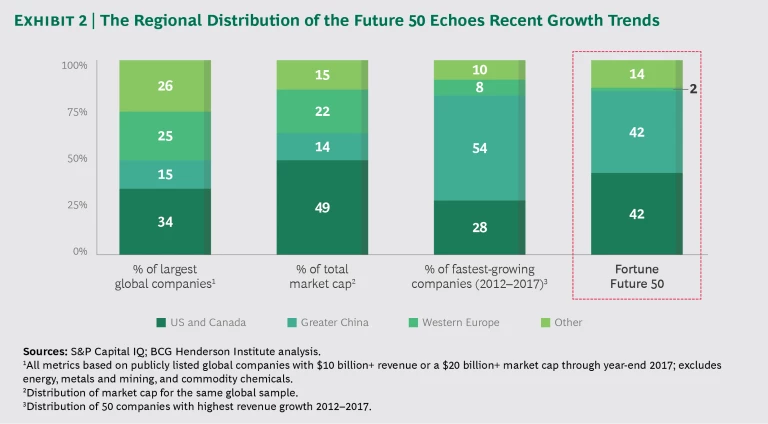

The global landscape of vitality suggests that recent growth trends are likely to continue. Over the past five years, the US and Greater China have accounted for more than 80% of the world’s fastest-growing large companies. (See Exhibit 2.) These two regions have also increased their hegemony in the digital economy, including in areas that portend future growth: for example, nearly 90% of global AI investments in 2017 were made in the US or China .

In contrast, vitality is especially challenging in areas such as Europe, where companies face a number of structural headwinds. Europe’s GDP growth has averaged less than 2% annually this decade, largely a result of demographic challenges—in particular, the decline of the working-age population since 2010. Furthermore, Europe’s economy is weighted toward less vital sectors: only 10% of its largest companies (weighted by market capitalization) are in digital sectors, compared with 33% in the US and China.

And the world’s top 20 internet companies are all now in those two countries. As a result, only one European company is included in the Future 50, although the region’s share increases to 10% when expanding to the top 200 firms.

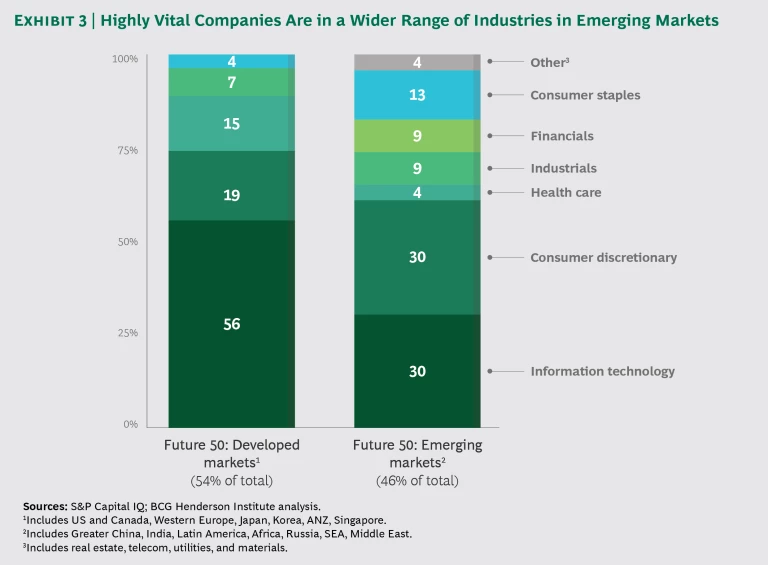

The global landscape of vitality is also unbalanced across industries—though the pattern differs by region. In developed markets, more than half of the most vital firms are technology companies, and many of the others are in discretionary consumer industries (including several internet-based businesses that are classified as consumer companies) and health care, echoing patterns we found in the 2017 ranking .

In emerging markets, vital companies can be found in a wider range of sectors. (See Exhibit 3.) The technology and consumer discretionary sectors are still the largest, but other industries are also represented—some of which are not generally thought of as high-growth areas.

For example, take Kotak Mahindra Bank (number 42 in our index). In developed countries, banking is generally a low-vitality sector—the market tends to be highly penetrated and tightly regulated. But the situation is different in India. Demand is growing as the economy matures, and state-owned incumbents are facing balance-sheet concerns. Kotak Mahindra Bank is in a position to take advantage of this opportunity: it has invested in new digital banking products, and it has a deeply ingrained long-term strategic orientation. As a result, it has achieved 24% annualized revenue growth over the past three years.

How to Enhance Vitality

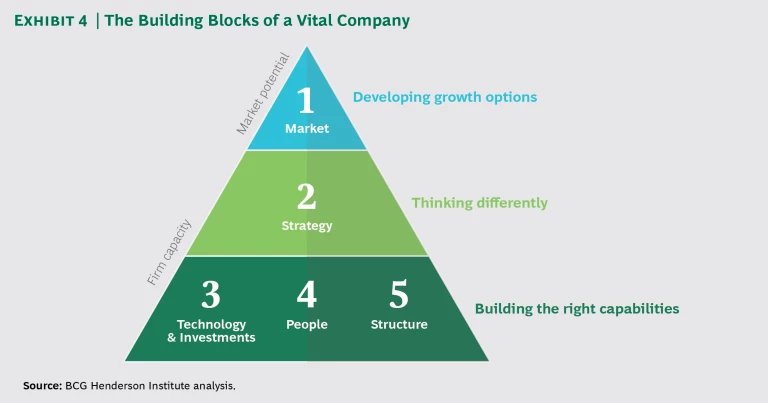

Our index, and the 50 companies that score most highly in it, reveal the building blocks of a vital organization . (See Exhibit 4.)

Continuously Develop Future Growth Options. This is the main driver of vitality. To achieve it, incumbents must create a balanced portfolio of bets across different timescales, which can cumulatively fuel sustainable growth over the long term. This requires an entrepreneurial spirit, a constant flow of new ideas, and a willingness to take chances on unproven models.

For example, Baidu’s (number 15) current growth is driven by its recently introduced news feed as well as its legacy search business.

Think Differently About Strategy. This includes taking a long-term perspective, focused as much on exploration as on exploiting existing business models, as well as thinking beyond the traditional models of management and strategy.

In particular, leaders must master adaptive and shaping strategies. The classical approach to strategy and execution, based on episodic analysis and planning, is often ill suited to today’s uncertain, dynamic business environments . Instead, companies need to take a more adaptive approach—creating business systems to seed, test, and scale new ideas in a rapid and iterative fashion—as well as building capabilities to disrupt, create, and shape their markets.

For example, Alibaba (number 14) has a highly flexible organizational structure and a culture of experimentation, which combine to create what the company calls a self-tuning enterprise that constantly adapts to changing customer needs. In addition, it orchestrates a vast ecosystem of sellers and partners, which it uses to shape the evolution of China’s e-commerce market.

Build the Right Capabilities. Three areas are especially important for incumbents to execute on their strategy and sustain vitality.

- Investing in Technology. Technology capabilities are increasingly critical—even for companies that are not in traditional digital sectors. Our analysis has shown that the least vital incumbents often have weak technology portfolios and capabilities. As the “real world” becomes more and more digitized (via sensors and connected products), tech capabilities will be critical for growth in all industries.

For example, Suning.com (number 35) was founded as an offline retailer, but it undertook an “offline-to-online” transformation to develop e-commerce and third-party platforms. By 2017, nearly half of its sales were online, and e-commerce was its main growth engine. Additionally, the company has invested in AI and facial recognition startups to power autonomous stores and smart warehouses, helping it become a Fortune Global 500 company for the first time in 2017.

- Maintaining Dynamism and Diversity. A variety of perspectives and ideas can help companies identify new opportunities and avoid being blinded by legacy practices. Businesses with a diverse workforce—measured not only by national origin and gender, but also by work and educational experience— are demonstrably more innovative in aggregate . However, to take full advantage of diversity, companies must foster a work environment that encourages the collision of ideas.

For example, Workday (number 1) has a relatively diverse workforce for its industry, which is accentuated by a dynamic culture: the company maintains a mindset of “ find a need and fill it, ” which allows employees to try out new roles without following standard career trajectories, spreading new ideas and perspectives throughout the organization.

- Creating a Sense of Urgency to Foster Self-Disruption. In an age of disruption, large, incumbent companies need to take preemptive action to avoid obsolescence. This can happen through an internal catalyst (for instance, by incubating new models separately from the core business) or an external one (by acquiring disruptive companies with the goal of achieving post-merger rejuvenation ). However, to successfully self-disrupt, leaders must avoid the trap of complacency and instill a sense of urgency throughout their organizations.

For example, Intuit (number 44) has reinvented itself throughout its 35-year history, thriving even as the software industry underwent successive waves of major change. In recent years, the company has massively accelerated its product development cycle, introduced subscription-based services, and opened its platform to outside developers. By “savoring the surprise”—focusing on the users whose behaviors do not fit the expected molds—Intuit is able to maintain the sense of urgency needed to keep challenging its current business model. Focusing on anomalies is one powerful way of anticipating change.

With High Potential Comes High Risk

Vitality operates over long timeframes, so our index should not be assessed on short-term results. That said, the early indications are positive: last year’s Future 50 has as a group grown by 18% with TSR of 35% since publication, outperforming not only the broader market but also growth-focused indices.

However, while we believe our index predicts vitality in aggregate, success for any specific company is not guaranteed. With high growth potential comes elevated risk . Our ranking this year includes a “high uncertainty zone” comprising a few companies that demonstrate high vitality but face situations that also elevate the chances of growth stalling, such as trust crises, political risks, or high dependence on one individual.

Furthermore, those sources of uncertainty seem to be growing: Customers are increasingly concerned with the social and political externalities of digital products. Many tech companies have to deal with aging pains, such as the transition of power away from founders. Trade friction and political uncertainty are upending the established rules of business. Finally, many high-growth firms are not yet profitable and are therefore exposed to changing investor sentiment or slowing growth.

This underlines the importance of ambidexterity —the ability to perform and reinvent the business at the same time. Vitality is necessary, but companies also need to succeed in the present to survive uncertainty and finance the future.

Achieving ambidexterity is difficult. To do so, leaders must choose the right approach to strategy for each part of the business (for example, mature businesses require different approaches than emerging growth engines do). To manage this contradiction, it can help to structure the company to facilitate multiple approaches.

For example, Alphabet (number 32) is the product of Google’s reorganization to separate its core business from its “moonshots.” In its current structure, Alphabet has continued to dominate search in nearly all markets around the world and at the same time has made promising new bets, such as the autonomous vehicle unit Waymo—while managing each type of business very differently.

Vitality is a crucial condition for sustainable success. By looking forward, rather than backward, incumbent companies can better understand the challenges and opportunities they face—and renew and reinvent themselves accordingly.