In the creative world, the tiniest of ideas can spark a masterpiece. But ideas and the people behind them need nurturing. This message rang out loud and clear as we explored the ways in which governments around the world are working to turn their creative industries into engines of economic growth. Policymakers everywhere are embracing a sophisticated range of investments and forming partnerships with businesses and investors as well as schools and universities. Countries that want to compete in this arena cannot afford to stand still.

It’s hard to underestimate the benefits of successful promotion of the creative industries. Investing in these industries drives economic growth: in the UK, for example, the creative industries generated £91.8 billion in gross value added in 2016, which represented year-on-year growth of 7.6%, compared with 3.5% for the UK economy as a whole, according to the UK’s Creative Industries Federation. The cultural and creative industries employed almost 30 million people worldwide in 2015, according to UNESCO. And, unlike other segments of the economy, the creative arts and entertainment also contribute to cultural identity and social cohesion.

It’s hard to underestimate the benefits of successful promotion of the creative industries.

We conducted research in 2017 in support of Sir Peter Bazalgette’s Independent Review of the Creative Industries , a project that was conducted on behalf of the UK government. We saw that governments recognize the need to ensure the financial viability of creative careers and to generate demand for local creative output. They work to boost market efficiency by reducing barriers to entry. And they understand the importance of fostering the connections that are so vital to creative professionals. We reviewed more than 240 interventions in over 20 markets, and we found that when governments take this holistic approach, they can accelerate the growth needed to deliver rich economic, cultural, and social rewards.

Capturing Opportunity Amid Diversity

The creative industries encompass a broad set of companies and media types. They bring together everyone from technicians and management professionals to artists and designers. Smart governments recognize that different creative industries have specific needs. Highly centralized programs may be appropriate in some cases; in others, local activities conducted in collaboration with stakeholders—from government, business, academia, and nongovernmental organizations—work best.

Enterprises also range in scale from independent professionals to small businesses to large studios. This means there is no one-size-fits-all model for supporting industry participants. And more than in many parts of the economy, policy interventions—most importantly those that aim to nurture creative talent and encourage the development of intellectual property (IP)—need to be carefully targeted to help individual artists and creative companies of all sizes to succeed.

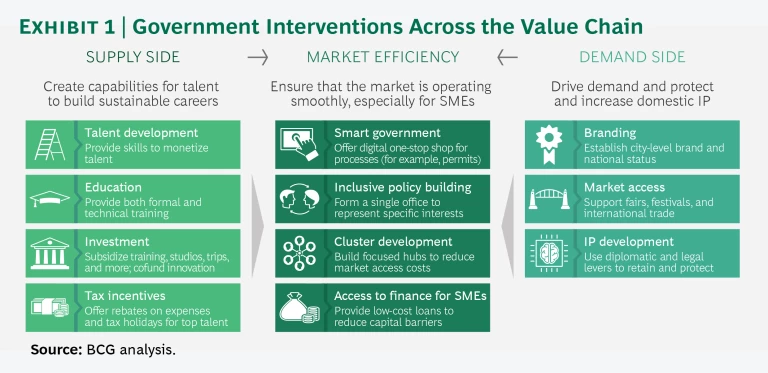

Our research focused on cataloging and assessing government interventions holistically, across the value chain. We looked at how they are fostering the supply of talent and capabilities, generating demand for creative content and IP, and ensuring that the marketplace is efficient and frictionless—interventions that we categorized as supply side, demand side, and market efficiency. (See Exhibit 1.) We looked in particular at three major creative industries: film and TV, music, and video games.

Building the Film and TV Ecosystem

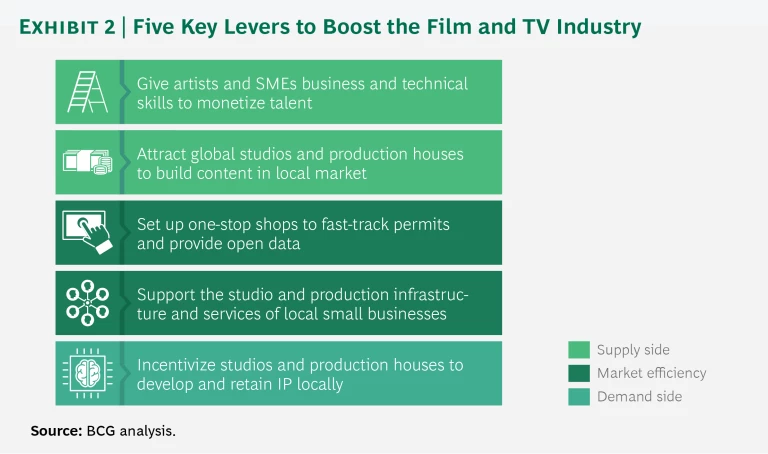

One core challenge is to foster a supporting ecosystem for film and TV by developing service providers (such as visual-effects artists, set designers, and audio-equipment providers), which tend to be small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs). Another is to increase access to affordable studio and production infrastructure. Meanwhile, training is essential, to give individual artists and SMEs the business and technical skills they need in order to monetize their creative talents. (Exhibit 2 shows five ways that governments are supporting film and TV businesses.)

Some governments are investing in smaller studios to develop talent and retain IP. For example, IDC (the Industrial Development Corporation of South Africa), a government institution, provides equity and coinvestment venture capital in production facilities and can take stakes in high-risk, high-return projects.

Governments are also looking to boost foreign direct investment by encouraging leading global studios and production houses to create content in their markets. Some have implemented investment incentives; Malaysia, for example, gives foreign TV and film production companies a 30% cash rebate in return for a minimum local expenditure.

In New York City, the Mayor’s Office of Media and Entertainment is building skills locally by working with industry on training programs intended to boost the skills of those already working in the industry and to encourage young people to enter it. Initiatives include a production assistant program that gives unemployed city residents training and entry-level placements in film production, and a program for media company employees that covers up to 70% of the cost of training in technical, creative, and business skills.

Meanwhile, to drive market efficiency, some governments—such as India’s, through its Film Facilitation Office—are creating one-stop shops that can fast-track permits and provide data and information on public shooting locations. National film offices and one-stop shops are relatively inexpensive and easy to set up but can be highly effective in driving economic growth in the industry because they can help attract large productions. (See the sidebar “Film and TV in Asia: A Coordinated Approach.”)

Film and TV in Asia: A Coordinated Approach

In looking at how to accelerate the development of their film and TV industries, governments of emerging markets in Asia are not taking the approach used by mature markets such as the US and the UK, where policy interventions have often evolved organically and at the national, state, and city levels. Instead, countries such as Malaysia, China, and India are implementing large, coordinated interventions aimed at exposing their artists and directors to more mature markets, building up their talent pool, and investing in critical studio infrastructure.

Malaysia, for example, formed a strategic alliance with the UK’s Pinewood Studios to invest in the creation of Pinewood Iskandar Malaysia Studios, the largest independent integrated production studios in Southeast Asia. The $400 million studios have enabled the country to attract both domestic and international filmmakers and to cater to the growing TV production industry.

In China, one approach has been to establish the China Film Co-Production Corporation. The State Administration of Radio Film and TV set up the CFCC to foster partnerships with global players with the aim of generating more Chinese-influenced global film content. It plays an administrative role, managing coproduction applications, providing step-by-step guidelines for online applications, and facilitating visas for foreign film crews and customs clearance for equipment and other materials.

Meanwhile, India has taken steps to remove bureaucratic hurdles to filming, which until recently required navigating a decentralized government structure of 36 regional councils, with permitting required at the national, state, and municipal levels. The Film Facilitation Office—established by the Ministry of Information and Broadcasting—now manages film centrally and has streamlined processes and created an online portal that provides a single window for facilitation and clearances.

Creating Sustainable Careers in Music

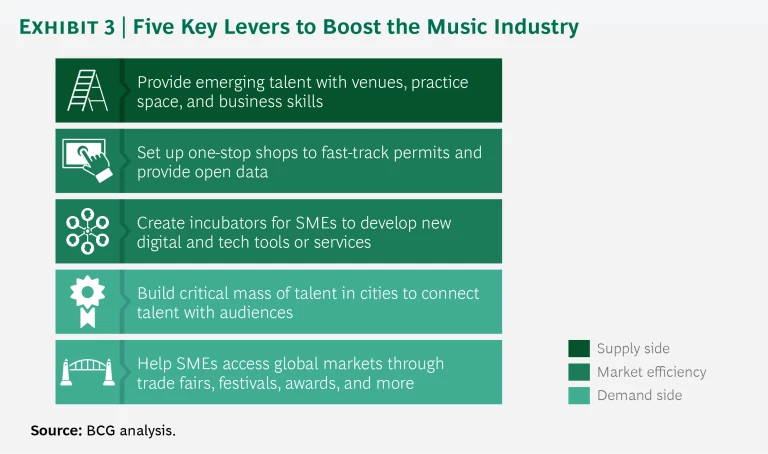

For this industry to thrive, governments must make it possible for artists to monetize their talents and build financially sustainable careers. Ways of doing this include expanding access to performance, production, and practice spaces and reducing the cost of living. Specific government initiatives range from funding training programs and providing incubators to fostering nationwide music hubs that provide artists with the space to rehearse or find affordable urban living space. (Exhibit 3 shows ways that governments are supporting music businesses.)

In Nashville, for example, Ryman Lofts, developed by the Nashville Music Council of the United States, provides subsidized living for vetted musicians. And in Canada, the Toronto incubator Transmedia Zone houses the Music Den, which provides a collocation space for the creation of innovative, tech-related tools and services for music by offering mentorship, technical equipment, recording studios, and editing suites.

When it comes to training, programs sometimes go beyond building technical skills to equipping artists to survive financially. Canada’s Music Incubator, an entrepreneur program for artists, is a leading example. It brings together stakeholders from across the industry with government backing to provide subsidized business education on topics such as music copyrighting, social media marketing, and signing with recording companies.

In some cases, governments are making large infrastructure investments. South Korea has invested in venues such as the $200 million Gocheok Sky Dome, used for K-pop concerts that attract national and global stars. The South Korean government is also establishing 29 Korean cultural centers in 25 major countries to spread the popularity of K-pop globally.

Another means of developing local demand is to support the creation of trade fairs and award shows as a means of expanding artists’ reach to international markets, while city branding helps connect talent with audiences and boost local business broadly. (See the sidebar “Music in Nashville: Building a Brand.”)

Music in Nashville: Building a Brand

To reinforce Nashville’s status as a music industry leader, the Mayor’s Office is backing a series of broad measures. The Music City Music Council, which represents a diverse collection of industry-leading stakeholders that focus on helping music-related businesses expand or relocate to Nashville, underpins the initiative. It works to bring televised music performances and music-related award shows across all genres to the city and to recruit music-related events and conventions.

Meanwhile, the Music City branding and logo are used to drive tourism to the city, with YouTube videos and apps promoting live-music and music history locations. Nashville also cobrands itself with local businesses by naming a local brand champion each month. The program highlights individuals and organizations that are integrating or developing the Music City brand in an innovative way—previous winners include local restaurants, hotels, the Nashville Public Library, museums, radio stations, and large corporations.

Meanwhile, as in film, governments are setting up one-stop shops to fast-track permits and provide access to public data such as information on audiences and available performance spaces. This has been the approach in New York City, where the Mayor’s Office of Media and Entertainment set up a one-stop shop for the city’s music industry. In addition to creating simplified permit applications, the hub facilitates permits for festivals and busking, while the city’s SpaceFinder database makes it easy for musicians to find rehearsal and performance locations. Some governments have established other types of units to represent musicians, as in New York City and Nashville, where dedicated municipal offices explicitly deal with music administration and policy.

Achieving Scale in Video Games

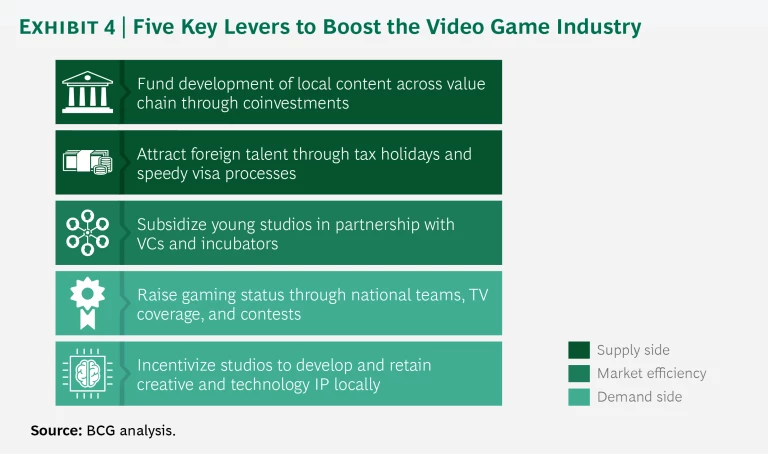

A key policy objective in this high-risk industry is ensuring that smaller game studios can survive and achieve scale. This can be done through a range of measures, from financing businesses through subsidies, coinvestments, and the involvement of venture capital to supporting a healthy talent pipeline by establishing incubators and offering training opportunities. In Canada, for example, the government teams with venture capital funds to coinvest in small local studios. (See the sidebar “Video Gaming in Canada: A Holistic Approach.”)

Video Gaming in Canada: A Holistic Approach

As Canada seeks to develop its video-gaming industry, it faces competition from the US, which leads the way in video gaming and creates the lion’s share of value in the industry. And in Asia, new industry players are emerging rapidly. The question Canada must ask itself: How can we create the capabilities we need to compete? In response, policymakers are taking a holistic view, with initiatives that range from coinvesting to launching national video game awards.

In British Columbia, for example, to support video game companies—most of which are SMEs with limited budgets that require financing to develop and sustain a large portfolio of games—the provincial government has established the BC Renaissance Capital Fund, a venture capital fund that coinvests in the technology sector (including video games) as a limited partner through eight VC fund managers. The fund has so far supported more than 30 local companies and helped create more than 1,000 new jobs.

Meanwhile, the Quebec provincial government subsidizes employee salaries for video games developed locally, at a rate of 30% plus an additional 7.5% if the games are in French. As a result of this and other measures, Quebec is estimated to have generated a net inward investment of about C$1,180 million in ten years, from an initial outlay of C$587 million.

On the demand side, the country also works to raise the profile of video games. For example, the Montreal International Games Summit is a platform for recruitment, investment, and public awareness, and the annual Canadian Video Game Awards recognize top companies and developers.

It also gives grants to large studios and production houses to open local offices and create local jobs. (Exhibit 4 shows ways that governments are supporting video game businesses.)

As in other creative industries, a priority is to ensure that emerging artists and small businesses have access to investors, resources, and industry expertise. For example, the Sweden Game Arena, a video game hub in Skövde, is a private-public partnership that helps students work together to develop games using government-funded offices, equipment, and expert counsel. It also help link students and startups to established companies and investors.

Meanwhile, tax holidays and fast-track visas are a means of bringing in foreign star talent. In Japan, for example, the government issues work visas to international video gamers through a system similar to that used for professional athletes.

One proven way to raise the status of gaming is to turn it into a national sport, supported by contests and TV coverage. In 2000, the South Korean Ministry of Culture, Sports and Tourism established the Korea e-Sports Association (KeSPA) to promote e-sports nationally. In 2003, China recognized e-sports as an official sport; in 2008, it selected a video gamer celebrity as a torchbearer for the Beijing Olympic Games. Thanks in part to the pioneering efforts of these countries, e-sports will be a medal event at the 2022 Asian Games.

To support video game businesses (especially those that include artificial intelligence, virtual reality, and augmented reality), governments need to provide incentives for studios to develop and retain creative and tech IP locally, as we’ve seen in the film and TV industry. In France, for instance, the Support Fund for Videogames (FAJV) was established to offer subsidies to local companies that are creating content and keeping their IP rights. In 2015, the FAJV supported 47 such projects with a total of €3.8 million.

Connecting the Dots

Our research reveals that one-off interventions or programs that evolve organically are no longer sufficient for developing globally competitive creative industries. Today, governments need to become more strategic, targeting interventions that increase the supply and sustainability of creative talent, that encourage demand for and development of local IP, and that foster a more efficient and robust creative ecosystem. Most importantly, they must recognize the need to link these interventions and to take a more coordinated approach.

The starting point should be a baseline assessment to ascertain what is currently working and what is not. Such an assessment can also determine which industries are contributing most to the economy and where potential for growth exists. It is also important to map out the range of stakeholders—from investors to universities—that can contribute to growth in the creative industries.

On the basis of this assessment, countries can design a strategy, setting out the scope of the public sector’s role and identifying creative industries to support. The strategy should prioritize areas where public-sector interventions can have maximum impact or where the market is failing. Policymakers can then design and test interventions and solicit feedback from stakeholders to decide which interventions will be most effective.

Policy and budget changes will be needed to implement the strategy and targets, and KPIs must be set to enable the evaluation of outcomes. Once KPIs have been established, governments can work with industry to monitor and adjust plans accordingly.

Critically, developing government interventions that support the creative industries demands a flexible and innovative approach from a cohort of policymakers prepared to spread their net widely when it comes to engaging business, academia, and others. For those that get it right, this vibrant ecosystem offers a powerful opportunity: the potential not only to generate social value and sustainable employment but also to contribute to long-term GDP growth. Governments that take a strategic, coordinated approach to developing these industries will compete more effectively overseas and drive value that underpins a healthy economy at home.

This vibrant ecosystem offers the opportunity to generate social value, sustainable employment, and long-term GDP growth.