Enterprises everywhere should take this adage to heart: “Those who do not learn from history are doomed to repeat it.” The digital age promises a transformation as profound as the Industrial Revolution—a period that also happened to impose poor working conditions, child labor, lowered life expectancies, and social unrest (even amid astounding economic growth).

One lesson learned from the Industrial Revolution is that technological innovation requires, in parallel, social innovation. A key component of a workplace transformation is building a powerful, mutual bond between the employees and the enterprise—and ignoring this essential element can have disastrous consequences. By directly addressing that bond and doing so during the early days of the latest digital technologies, such as artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning, we have the opportunity to ward off threats and welcome instead an industrious revolution.

How? Through what we call a learning contract. The learning contract is designed to reinforce and enhance the modern enterprise-employee relationship. It requires employers and employees to commit to reskilling and upskilling for new roles—those performed today and those on the horizon—so that they are continually preparing for the next technological disruption in the workplace. Critical components of this new form of social contract, on both sides, include a continuous commitment, ability, and opportunity to learn.

This change in the skill imperative is vital: already, digital-age disruptions are upending the landscape of skills and education, and they will continue to do so. Many of the skills learned in traditional higher-education institutions are becoming irrelevant by the time employees reach their 30th birthday.

History instructs again: At the turn of the century, famed business thinker Peter Drucker predicted, “The only skill that will be important in the 21st century is the skill of learning new skills. Everything else will become obsolete over time.”

The only skill that will be important in the 21st century is the skill of learning new skills. —Peter Drucker

Companies are increasingly recognizing the survival-critical nature of learning. The issue needs to be on the CEO agenda. It’s time to redefine today’s employer-employee social contract by confronting digital disruption, using a learning contract to connect employees to learning opportunities, and reshaping roles within the organization to accommodate an intense focus on learning.

Turning Disruption into Development

The Industrial Revolution was built on two core technologies, the steam engine and electricity, which forced a deskilling of the workforce by replacing the work of skilled tradespeople with the productivity of machines. In contrast, the technologies of the digital age—information and communications technologies and AI—will require higher levels of skill and creativity from the human workforce: a reskilling (to help people whose skills have become obsolete) and an upskilling (to build new skills required by the digital age).

Thus, for enterprises, surviving the digital age and the disruptions that accompany it requires access to a workforce with a suite of new skills and competencies. That critical access rests on their ability to build and retain talent—specifically, the ability to effectively encourage a workplace mindset and culture primed to continuously anticipate change and develop new skills accordingly.

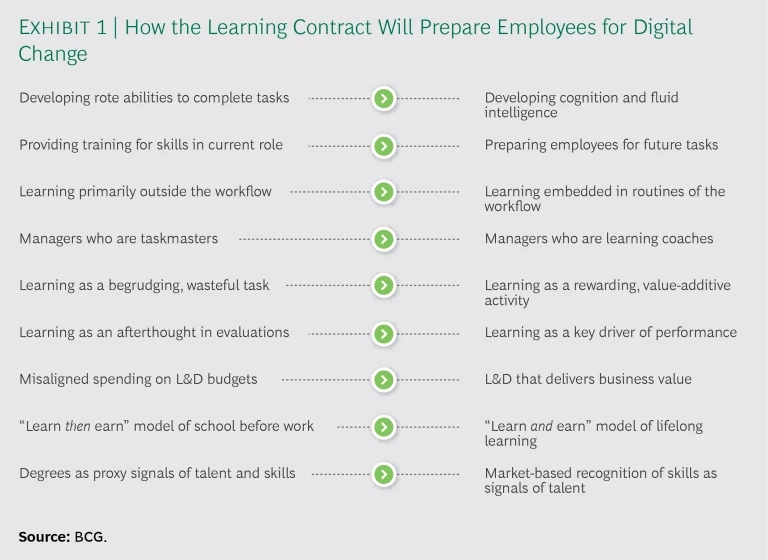

And for employees, the reality is that digital-age workplaces need certain new skills and don’t need certain old ones; to be employable, people need to become proficient in new areas, gain the skills valued in the digital age, and learn how to learn. (Exhibit 1 shows how the learning contract will change the employee experience.)

All of this means that enterprises and their employees must enter into a covenant—the learning contract—for ongoing skill development so that business performance can improve, enterprises can continue to thrive in the digital age, and individuals can remain meaningfully employed.

Understanding the Learning Contract

It’s important to understand two overarching aspects of the learning contract: it is one piece of an enterprise’s overall approach to workplace learning, and it consists of some core principles and some flexible characteristics that can be adapted to the enterprise. It is not meant to be just more paperwork or a legalistic addendum to an employment contract.

A Bridge to the Learning Offering and the Business Strategy

The learning contract does not replace an enterprise’s learning offering or displace its learning management system (LMS). Nor does it supplant the traditional learning and development (L&D) program. Its true purpose is to drive employee engagement with the existing learning ecosystem and connect employee aspirations to the organization’s intertwined business and learning strategies. The learning contract gives employees clarity into the company’s goals and empowers them to take ownership and be accountable for their learning and growth.

The learning contract gives employees clarity into the company’s goals and empowers them to take ownership and be accountable for their learning and growth.

It is incumbent on the enterprise to create an internal learning ecosystem that supports employees in this undertaking and accommodates different learning styles and needs.

But just offering a terrific opportunity for education and skill development is a passive and poor means of improving employees’ abilities. Many companies invest to build dynamic learning opportunities but fail to achieve employee engagement or even awareness; in those cases, the opportunities are grossly underutilized. One consumer goods company reported that only 6% of its 100,000 employees took advantage of its advanced learning offering.

The learning contract is the hitherto missing link that connects employee-learners to the learning offering by creating awareness, access, and purpose. With the learning contract in place, the learning offering is no longer a vague area of the organization that the employee might someday get around to exploring, probably when it’s time for the annual performance review, and then will promptly forget. Instead, the learning offering becomes a vital piece of each employee’s daily current—and future—work because it involves on-the-job learning and an explicit commitment.

Maximizing this engagement also means harnessing employees’ motivations in the directions that are most profitable for the company overall. The learning contract and the overall learning ecosystem are not intended just for employees’ benefit, of course. The enterprise’s needs and goals must be part of the continuum of benefits that accrue from learning and development.

A Blueprint That Outlines Core Principles

There is no one standard learning contract. Rather, enterprises can use a set of key core principles as a blueprint for building customized and adaptable learning contracts. Our experience globally and across industries indicates that the learning contract will look different everywhere: regions and economies have different legal structures and institutions, employment statuses, market sizes, and many other considerations.

Any learning program that deliberately seeks to embody the following core principles is operating according to a learning-contract model.

The enterprise must commit to measuring and rewarding business and learning outcomes. This commitment helps to ensure an increase in the return on learning spending. It also gives learners an accurate and valuable assessment of their learning and its relationship to their job. That assessment lets organizations identify the employees who have mastered new skills and applied them to advance the enterprise’s goals and strategies. These employees will be in line for recognition and rewards, like badges and certificates.

A meaningful measurement system will also make it possible for employers to recognize skills in new ways, different from traditional “proxy” credentials awarded by top universities and perhaps more relevant to the changing roster of needed skills.

Managers must coach and facilitate. The role of the manager will evolve from taskmaster to coach. This new breed of manager will facilitate and support the learning experiences that their employees undertake through the learning contract. Managers will orchestrate more deliberate and reflective practices, including routine check-ins, to better embed on-the-job learning into the rhythms and routines of each employee’s workflow. This includes encouraging employees to dedicate some work time explicitly to learning and even more work time to learning in the workflow; learning should be intertwined with work as much and as often as possible. This means that employees will bring their learning to work and apply it to their job—and vice versa, it means that applying new learning to actual job tasks is itself a means of learning. The best learning happens when it is done as part of real work.

Enterprises might balk at allocating a large share of time to learning at work, but programs such as Google’s Innovation Time Off, which devotes 20% of employee work hours to projects of their own interest, have shown increased productivity and innovation. Further, the specific percentage of time allocated to learning matters much less than the deliberate mutual effort by employees and managers to build learning into the workflow wherever possible. Some might argue that, in an ideal world, people are learning 100% of the time if they are really pushing themselves.

In an ideal world, people are learning 100% of the time.

But how will traditional managers develop the new skills they need to facilitate and support this learning on the job? Enterprises must launch their use of learning contracts with the manager cohort. Senior leadership must coach managers through their own set of learning-on-the-job initiatives that will address a variety of skills, including listening, judgment, vision, and critical evaluation. Managers will also need an in-depth understanding of the enterprise’s learning strategy as well as technical prowess for navigating the company’s LMS.

Employees must be encouraged to be accountable for learning in ways that benefit both employee and enterprise. The company will design the learning contract and the learning program that accompanies it, and managers will steer the processes of learning at work. But successful learning won’t take place if employees don’t take charge of their individual development.

The learning contract helps employees do that: it is structured to allow learners to pursue personal passions that align with corporate strategies, such as funding to support an IT manager who wants to learn more about AI and machine learning. It may not be an aspect of the employee’s job today, but it is most certainly a part of the future—especially if it’s an aspect that the IT manager is inherently interested in.

Accountability and autonomy are valuable features. Studies have shown that increasing learners’ choice and control engenders resourcefulness and efficiency. That means that each dollar spent on learning has more impact, and it means greater success in developing skills and deploying them in the workplace.

Learning contracts must be adaptive and aligned with corporate strategy. Frontline employees, managers, and senior leaders need to be part of an on-going discussion about both near- and long-term corporate strategies as well as the skill sets that will support those strategies. These discussions will guide the learning contracts that employees and their managers will put in place. They will create “aligned autonomy”—employees have the autonomy to pursue learning, but they do it with full knowledge of shared goals. Having a clear understanding of the future helps employees to seek out and select learning opportunities they can pursue to be prepared for their job today, tomorrow, and the day after that.

Implementing Learning Contracts

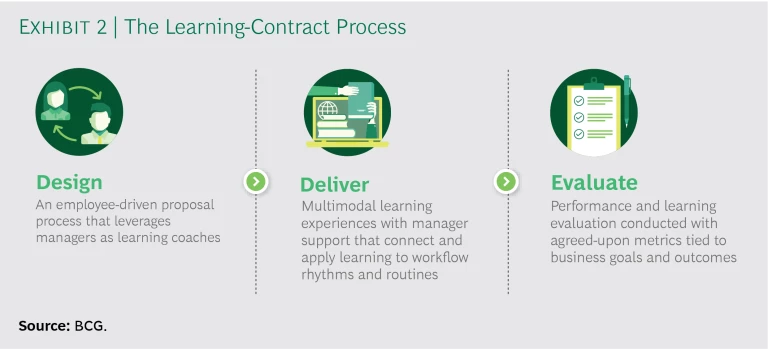

Enterprises can put a learning-contract program in place through three discrete steps. (See Exhibit 2.) Bear in mind: the high-performing enterprise will already have a learning strategy—which is closely paired with the overall business strategy—and a system of learning offerings. Employees who respond to the push-pull of the learning contract and initiate the process will benefit from these strategic offerings.

Design: Empower Employees to Learn

From the start, the enterprise should empower employees to drive the design of their own contracts in a proposal process. The employees will propose a set of skills that reflect their interests and are related to current and future workplace expectations. They will focus on skills that make them better at their current jobs as well as skills that prepare them for the future, especially the digital future. In addition, they will propose a learning pathway or curriculum to build those skills. (See “The Learning Contract in Action.”)

THE LEARNING CONTRACT IN ACTION

THE LEARNING CONTRACT IN ACTION

Katie works as a financial analyst for an industrial company with a highly advanced learning system that utilizes a learning-contract model. She would like to become more skilled in the use of software for tracking and interpreting data on stakeholders in the company. Katie approaches her manager, Bonnie, and proposes to attend a workshop sponsored by the software company, followed by an online course and on-the-job coaching from a peer who is very skilled with the software. Bonnie knows that the software will be a part of the company’s plans for this department over the next two or three years and that Katie will benefit from improving her skills. She will also be more productive, handling and processing an increasing amount of work as a result.

Bonnie and Katie work out a three-month program that begins with the workshop, continues during the online course, and concludes with the peer coaching. They agree to meet every three weeks to discuss this learning plan and how it is working on the job, and they establish a goal for processing a larger amount of work with fewer errors.

At the end of the three months, Katie’s evaluation shows that she has become more efficient as a result of improving her knowledge of the software, and she is rewarded with a 3% raise. She also receives a digital badge (which she adds to her internal email signature) that signals to her peers that she can help them to learn the software if they encounter problems.

The ideal scenario for leaders: to head up a workforce composed of gifted battalions of passionate self-improvers who have a natural zeal for learning.

The reality: it takes effort and thoughtfulness to build motivation among employee-learners.

Managers must boost motivation by helping employees find ways to overcome obstacles in the workplace and achieve their goals as individuals and as employees. During the process of designing the learning contract, the manager must determine whether the proposed skill mix and suggested pathways are aligned with the enterprise’s strategy.

How to determine this? Usually through conversations with team members and leadership. Then, the manager could suggest alternative pathways for learning, all the time considering—perhaps using competency maps and forecasting—which skills would support the employee in his or her current and future roles.

Once this process is complete, the employee and manager will agree on a way to measure learning and its application; this could be a targeted KPI or a less formal measure (the latter may be best for soft skills such as communication or collaboration).

Deliver: Put the Learning Offering into Action

One key aspect of this approach to learning is that employees should be applying the skills they are acquiring to the work they’re doing, in real time. For example, an employee in sales who is learning about proposal and pitch strategies should use and practice those skills in ongoing work. An employee learning how to use Tableau data visualization software should learn it in the context of a real work task and use those skills to develop more engaging presentations.

Employees should be applying the skills they’re acquiring to the work they’re doing, in real time.

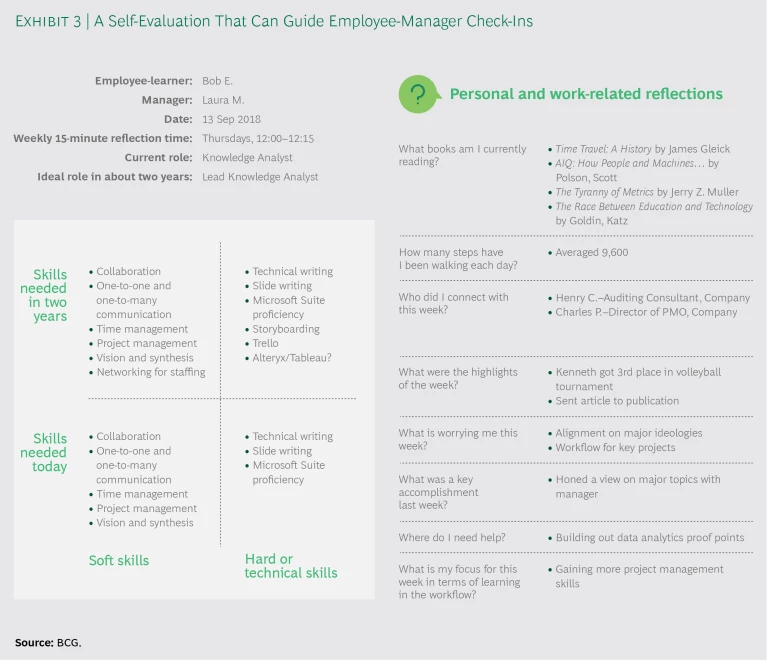

Employees should touch base with managers at regular intervals to further integrate new learning into the workflow and ensure that the learning is having a positive impact on both the employee and the enterprise. A self-assessment like the one shown in Exhibit 3 can help facilitate the discussion. It’s also an opportunity to develop the employee by helping to create a better understanding of his or her relationship to the work and the company overall. Sometimes, the check-in will reveal that a learner is not getting the expected results or is not finding the learning meaningful. In that case, the learner and manager should abandon that pathway and find a better one. These learning check-ins will be vital to cementing the relationship between employee and manager.

This kind of learning and performance evaluation might already happen in some companies, but the learning contract provides structure, expectation management, and control. Instead of one-size-fits-all learning opportunities, learning contracts let enterprises partner with employees to build and follow their own learning journeys deliberately.

Evaluate: Assess Performance and Reward Accordingly

The performance metrics that are defined during the proposal process will be revisited when it’s time for the employee evaluation. The evaluation will inevitably take into account input from a variety of sources for these metrics: managerial assessment, learner outcomes (including grades in formal courses and certifications), departmental improvement, as well as the employee’s self-evaluation.

This process should also involve reflection on the efficiency and impact of learning. Discussions should focus on specific methods for learning skills, areas of application, and the modes of learning that worked best for the employee.

The evaluation serves, then, as a chance for the manager and the employee to formally recognize the learning and assign rewards, promotions, or another form of recognition for the new skill set (if applicable). Enhanced recognition doesn’t have to come in the form of a raise or bonus; performance can be rewarded with more holidays, badges, the ability to work from home a few days a week, on-the-clock time to exercise, or free dinners, for example. These opportunities for recognition are vital, as they set the standard for learning in the workflow—they send the signal that learning at work provides value to the firm and is not just an obligation. Learners are more likely to want to learn when that learning is celebrated and rewarded.

The goal: a mindset by which employees say “I want to do this” rather than “I have to do this.”

Reimagining Traditional Roles

Learning contracts can reenergize organizations, improve long-term viability, increase returns on L&D investment, and ensure higher levels of recruiting and retention success. These impacts will be driven in part by changes in the roles of managers, frontline employees, and ultimately C-suite leaders.

Managers as Learning Coaches

Traditional management responsibilities—overseeing tasks, ensuring compliance, communicating, and mediating conflict—will remain necessary, but the learning contract demands much more of modern managers. In fact, the metamorphosis of the manager is the biggest role change involved in the learning-contract initiative—but managers with the skills to ably coach employees will be among the most valuable assets in the digital age.

The role of managers is undergoing the biggest metamorphosis—they now must be learning coaches as well.

Managers are well placed to understand how their subordinates’ tasks and skills directly relate to achieving business goals. In a recent LinkedIn Learning survey, 56% of employees said they would be more likely to take a development course if it had been recommended by their manager.

As noted previously, managers will need to build new skill sets to carry out this role. The traits reserved for yesterday’s executives will be needed by tomorrow’s mid-level managers to ensure that companies are getting the most out of their people. The manager must foster an environment where the very act of learning is respected, by setting an example and visibly dedicating time during work for learning.

Managers will also need access to knowledge about corporate strategy on a granular level to understand what each employee will be doing at intervals in the future. Tools like competency maps and skill taxonomies will help managers to coach employees for their future jobs.

Employees as Learners

In the legacy model, becoming an employee meant shedding the skin of a student. Young people graduated and entered the workforce expecting to never sharpen another pencil.

The new workscape is different. Jobs that do not require any ongoing learning will likely be the victims of automation during the digital age. Digital-age employers need to hire people who are both forward-thinking and adaptable to meet ever-evolving needs. Simply put, employees must prepare to make learning a priority.

People who see themselves first as learners—rather than primarily as consultants, engineers, analysts, or another occupation—are more likely to approach every task or responsibility as a learning opportunity. They’re also more likely to be receptive to feedback, since it is part of the learning process. These individuals have a high intrinsic motivation to learn. Other employees will need to develop the motivation to identify as learners and then to “learn how to learn.” The employee-learner is the new norm.

The most successful employees will possess or develop what psychologist Carol Dweck has termed a growth mindset. In contrast to a person with a fixed mindset, who thinks that intelligence, kindness, and other attributes are innate and static, a person with a growth mindset believes such attributes can be developed and improved with practice.

With a growth mindset, enterprises and individuals can develop a high “learning velocity”: the rate at which people learn relative to the time set aside for that learning. The learning-contract model is designed not only to leverage learners who already have a high learning velocity but to help others build a growth mindset that allows them to develop a higher learning velocity and become more capable contributors to the company’s overall goals.

An Entire C-Suite of Chief Learning Officers

The roles of executives and senior leaders must change under the learning contract. HR and learning leaders will continue to have key input and responsibilities, but leaders across functions must actively contribute to discussions about future talent needs and how the organization can build the learning ecosystem to address them. Recruiting, hiring, developing, and retaining human capital while integrating technological innovations alongside the workforce are keys to digital-age success, so they should be closely coordinated across the organization.

In the new workscape, employees will self-direct their learning and managers will coach them. How will they all know they’re advancing corporate goals and value? Executives must be clear and thorough communicators of corporate strategy. Aligned autonomy works only if leaders take a deliberate and principled approach to clearly define the goals of the company and what employees must learn to advance those goals. They must also serve as role models, showing themselves to be deliberate, lifelong learners.

Executives must also serve as role models, showing themselves to be deliberate, lifelong learners.

CEOs can no longer take a hands-off approach to learning and development; rather, their fingerprints must be all over the company’s learning strategy with the understanding that building a dynamic human-capital portfolio is a vital investment in the company’s future. It might seem risky to develop employees with marketable skills, but neglecting their skills and growth is even riskier.

What You Haven’t Experienced About Learning Contracts—Yet

Aligning business strategy and learning strategy is not a new concept, but doing so is often a small step, taken incidentally. Company executives meet to discuss near- and long-term strategies; they might turn to an L&D representative for input. Rarely, though, do enterprises consider the deliberate application of those strategies to the learning objectives for each individual in the firm.

The learning contract makes that step deliberate. It makes it, in fact, a giant leap.

When learning is ingrained at the individual employee level and consciously aligned with enterprise goals, organizations change, both in direct intended ways (becoming more digitally skilled, for instance) and in ways that are more oblique, more monumental, and more valuable—they gravitate toward a growth mindset that positions them to become adept at anticipating, accommodating, and optimizing change.

How will you know when your enterprise has achieved a growth mindset? Listen for one key word, voiced across all levels of the organization.

Do you know how to use Tableau to build this presentation? I haven’t learned that—yet.

How will your business unit digitize the supply chain in emerging markets? We haven’t figured that out—yet.

Does your organization have a plan to take the necessary steps to thrive in this age of digital disruption? Probably not—yet.

The BCG Henderson Institute is Boston Consulting Group’s strategy think tank, dedicated to exploring and developing valuable new insights from business, technology, and science by embracing the powerful technology of ideas. The Institute engages leaders in provocative discussion and experimentation to expand the boundaries of business theory and practice and to translate innovative ideas from within and beyond business. For more ideas and inspiration from the Institute, please visit Featured Insights.